Shalon van Tine

To understand how cultures and technologies have evolved over time, historians rely on written records that explain people, transactions, events, and traditions. However, this approach is limited as systems of writing were invented less than six thousand years ago. Since the earliest human tools date back to at least 2.6 million years ago, historians differentiate between history and prehistory, which is the study of human history before written records. Without written records, historians work with anthropologists, archeologists, paleontologists, geologists, botanists, paleobiologists (who examine fossilized remains of dead biological life), and linguists to help make sense of the prehistoric world.[1] By studying fossil remains, tools, dwellings, and other cultural artifacts, these specialists are able to construct a vivid picture of life for prehistoric humans. The study of prehistory covers all aspects of human culture from the Paleolithic Period to the birth of civilizations during the Neolithic Period.

Paleolithic Period—circa 2.4 million years ago to 8,000 BCE

The development of technology corresponds to the evolution of humankind. Compared to the timeline of the universe, humans have only existed for an extremely short time. The universe came into existence around 13.6 billion years ago with the Big Bang.[2] The Earth formed about 4.6 billion years ago, and dinosaurs ruled the Earth around 200 million years ago.[3] After the extinction of the dinosaurs, some smaller mammals evolved into primates, which are animals that include monkeys, apes, and humans.[4] It was only about 2.4 million years ago that primates evolved into a new branch that would lead to the modern human.

The Paleolithic Period, also called the “Old Stone Age,” marks the era when hominids, or the earliest humans, began walking upright, which was around three million years ago.[5] One of the first of these was Australopithecus, who had a slightly larger brain than earlier primates and was bipedal, meaning it walked on two feet (fig. 1).[6]

Figure 1: A skull of Australopithecus Afarensis. Photograph by Tiia Monto. Naturmuseum Augsburg, Germany (public domain).

Being able to walk on two feet was a necessary condition for the development of technology since bipedalism frees the use of the hands to create tools. Coexisting with Australopithecus was Homo habilis, also known as the “handy man.” Homo habilis created the first human tool: simple choppers, or sharp-edged stones, which were used as cutting tools to crush bones or hack roots (fig. 2).[7]

Figure 2: A simple chopper, which was commonly used by Homo habilis. Photograph by Didier Descouens. Muséum de Toulouse, France (public domain).

While humans are not the only animals that utilize tools, it seems that humans may be the only ones to create new tools from previously-made tools.[8] This process of toolmaking indicates a major shift in human evolution—one that marked human mastery over the environment and allowed for all subsequent human advances in technology to spring forth.

After Homo habilis came Homo erectus, who was larger in size and had a bigger brain than Homo habilis.[9] Homo erectus emerged in the evolutionary record around 1.8 million years ago and became one of the first human ancestors to migrate outside of Africa, spreading to the temperate and subtropical zones in Afro-Eurasia.[10] Homo erectus achieved an important technological development: the mastery of fire. The technology of fire allowed Homo erectus to extend human activity into dark places such as caves and to stay warm in colder areas.[11] Fire could also be used to cook food, making the food easier to digest.[12] Additionally, Homo erectus refined the hand axe, which improved the ability to hunt.[13]

About a half million years ago, these species splintered into different branches. Homo neanderthalensis was one of the first to demonstrate human rituals of caring for the sick and burying the dead (fig. 3).[14]

Figure 3: A Neanderthal burial. Photograph by Carol Tomylees. Natural History Museum, London (public domain).

Homo neanderthalensis also developed a verbal language, a trait shared with Homo sapiens, the modern human species. Even though Homo neanderthalensis became extinct around 40,000 years ago, both Homo neanderthalensis and Homo sapiens developed the capacity to share symbolic information in a way that was more complex than other animals.[15] While some animals, such as bonobos and capuchin monkeys, may understand some basic symbolic information, humans are the only animals known to demonstrate more complex symbolic understanding, such as dancing, creating art, and using verbal language.[16] Scholars are unsure exactly how spoken language evolved, but the emergence of language reflected cognitive development in early humans.[17] Language enabled Paleolithic humans to create culture, or knowledge and ideas that are passed down from one generation to the next.[18]

A key aspect of Homo sapiens culture was not only the creation and use of tools, but also the design of social rituals that accompanied the reality of death. An example of this development is found in Paleolithic burial sites. Paleolithic burials show skeletons wearing beads and resting in a prearranged position, signifying that early humans understood death on a conceptual or abstract level.[19] Paleolithic art in the form of figurines, cave paintings, personal adornment, and early forms of music and dance demonstrate that humans were able to communicate dense religious ideas in a creative way.[20] By producing a wide variety of cultural objects, such as stone tools, hunting weapons, sewn clothing, shelters, and lunar calendars, Homo sapiens changed the way humans reacted to their environment in a way never before seen. These conditions set the stage for more complex societies and technologies that were yet to come.

Paleolithic Technology

Paleolithic humans were nomadic, surviving by hunting and gathering their food.[21] They were organized in small bands of people, typically consisting of members who were all closely related.[22] The technology used in hunter-gatherer societies primarily functioned to increase their food supply and protect them from the elements. Women were responsible for gathering edible seeds, plants, and eggs, while men were responsible for mainly hunting animals.[23] Paleolithic humans used wood, stone, or animal bones, teeth, and antlers to create early tools for use as digging and scraping implements, hand axes, spears, fishing hooks, choppers, and animal traps.[24] These early tools helped humans collect the food supply necessary for survival.

In addition to food-related skills, Paleolithic humans developed tools used for everyday activities. One example of this was the use of lunar notation systems, which date back to the Upper Paleolithic period.[25] Lunar notations tracked the cycles of the moon, helping Paleolithic humans follow animal migrations for hunting. Hunting large animals was a grueling task that often required many men following herds for weeks at a time. To aid with this difficulty, lunar cycles were carved onto bone or antler and carried along for the journey.[26] These notation systems may also have been used in religious ceremonies or fertility rituals.[27]

Other skills may have included making shelters, clothing, and art. Because Paleolithic people were nomadic, they did not settle down in one place to establish permanent settlements. The most well-known examples of shelters are caves; however, thatched huts have also been found in prehistoric campsites, suggesting that Paleolithic humans built temporary shelters outside of the standard cave dwellings.[28] These huts often used large animal bones as a base and had a hearth and a hole in the roof where smoke from a fire could be released. Additionally, they contained grass and fur bedding on the floors, which provided an extra level of comfort and warmth.[29]

Sewn clothing made of animal skins was another step forward in prehistoric technology by both Homo neanderthalensis and Homo sapiens.[30] In order to create clothing, Paleolithic humans used animal skins for leather and cloth and sewed them together with sharpened needles formed from bone, antler, or stone. A common animal type used for clothing in North America and East Asia was the reindeer, which provided both a sturdy hide and antlers that could be used for creating needles and awls (fig. 4).[31]

Figure 4: Paleolithic bone needle, circa 17,000 BCE. Photograph by Didier Descouens. Haute-Garonne, France (public domain).

Additionally, Paleolithic humans wore jewelry adornment in the form of twigs, beads, and pendants.[32] Beads require drilling holes into hard material, and because of this, one of the earliest rotary devices to be developed was the bow drill, a device used for starting fires and later for spinning textiles.[33]

In addition to tools developed for survival during the Paleolithic era, humans expanded their technological development to include artistic creations. In the nineteenth century, archaeologists discovered images that were painted or carved on the walls of caves around the globe. Some of these artistic endeavors extend back at least 40,000 years ago outside Europe, with some of the earliest art found in Indonesia.[34] Cave art was created by applying burnt coal and mineral pigments to the cave walls. Images ranged from basic symbols, such as handprints, to more complex images, such as bison, reindeer, elk, zebras, horses, lions, panthers, and mammoths (fig. 5).[35]

Figure 5: Paleolithic cave painting, circa 28,000–10,000 BCE. Photograph by John McLinden. Lascaux Caves, France (public domain).

While these images could have been used as calendars for hunting cycles, historians assume that they could have also served as a ceremonial or an artistic function. These cave drawings were often accompanied by carved figurines, usually in the form of animals or women with exaggerated features (fig. 6).[36]

Figure 6: Venus of Willendorf, circa 28,000 BCE. Photograph by Artúr Herczeg. Vienna Museum of Natural History, Austria (public domain).

Since these figurines emphasized female reproductive organs, historians hypothesize that these figurines may have been used in fertility rituals.

The Paleolithic marks the era when humans distinguished themselves by creating technology. Technology allowed humans to create cultural patterns and traditions that would later lead to settlement and the development of civilizations. The Paleolithic period ended around 10,000 BCE, which marked a new era called the Mesolithic. In the Mesolithic era, the Earth grew warmer and the Ice Age ended.[37] The mammoths died out along with many reindeer that remained in colder areas. Some humans followed the reindeer north, but others developed new methods for survival.

Around 8000 BCE, many hunter-gatherers began to inhabit areas and grow food. The process was gradual and occurred at different rates around the globe. Humans may have started experimenting with farming, or perhaps drier climates allowed them to stay in one place. This change evolved humans into the last major era in prehistory, the Neolithic.

Neolithic Period—8000 BCE to 3000 BCE

The Neolithic era, also called the “New Stone Age,” is the time when humans shifted from hunter-gatherer societies toward human settlements, allowing for the development of agriculture and animal domestication. This shift arose independently in various places around the globe and may have been facilitated by the Earth’s changing climate, which pressured human communities to exploit their available resources more intensively.[38] While the spread of agriculture seems fast in comparison to other prehistoric developments, the process was gradual and varied depending on the area. Domesticated plants began showing up around 9000 BCE: millet and small seeded grasses in north China, rice in south China, wheat in the Fertile Crescent, potatoes and beans in South America, and maize (corn) in Mesoamerica.[39] Domesticated animals also began to appear: dogs in both Europe and Asia, cats in Africa, and pigs, goats, sheep, and cattle in the Fertile Crescent.[40]

Because these changes permanently transformed the way humans interact with their environment, historians have labeled this shift the Agricultural Revolution (also called the Neolithic Revolution). The Agricultural Revolution set the stage for an agrarian world, a state of human existence that lasted until the Industrial Revolution of the eighteenth century. Because humans could now grow and store their own food, there was no longer the need to travel from one place to the next. Instead, Neolithic humans could settle in one area, grow their population, improve technology, and eventually develop large-scale societies. In essence, the Agricultural Revolution facilitated the rise of civilizations around the world.

Neolithic Technology

The Agricultural Revolution allowed Neolithic humans to grow and store food, which meant that they no longer needed to follow the hunting patterns of animals for survival. Historians are not sure what factors prompted humans to experiment with plants, but the results can be seen in a variety of agricultural technologies that developed during this time. Gathering food was replaced with gardening and plow agriculture, and irrigation was implemented to water crops. Early Neolithic peoples cleared land using hoes, digging sticks, axes, and adzes, a tool similar to an ax but with an arced blade (fig. 7).[41]

Figure 7: Adze, circa 1900 BCE. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (public domain).

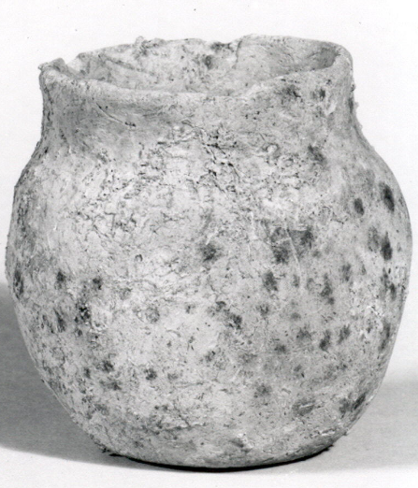

As plants were harvested, a collection of tools was needed to collect, thresh, and grind grain. The sickle was developed to harvest cereal grains, and the rotary quern, a hand mill for grinding grain, was invented to grind the grain into flour.[42] Early ceramic pottery was made by hand, dried in kilns, and used to both cook and store food (fig. 8).[43]

Figure 8: Pot from Iran, Neolithic period. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (public domain).

Another important aspect of the Agricultural Revolution was the domestication of animals. By selectively breeding animals to be manageable in terms of size and temperament, Neolithic humans could utilize animals in a variety of ways. First, domesticated animals provided good sources of meat and milk. Animal foods are rich sources of proteins, vitamins, and fats, improving nutrition and leading to larger human populations. Second, domesticated animals provided fibers (such as wool and hair) and leather. Animal fibers could be spun into textiles or rope, and animal hides could be used for clothing, blankets, shelters, harnesses, drums, and other uses. Additionally, other animal parts, such as teeth, bones, and horns, could be used to create tools, jewelry, and weapons. Third, domesticated animals provided labor. Oxen and horses were harnessed and put to work in the fields. Where early farming techniques had to be done by hand, the introduction of the ox-plow, a tool used to prep the soil for the planting of seeds, allowed that task to be completed by draft animals instead.[44] Oxen were domesticated as early as 7000 BCE in Africa, and farmers began to use horses around 3500 BCE in Central Asia. In addition to farm labor, dogs were used to herd sheep and cattle, and horses and camels were used for long-distance travel. As one of the earliest domesticated animals (beginning as early as 12,000 BCE), dogs have proven indispensable to humans in Europe, Asia, and the Americas for their ability to aid in herding and hunting.[45] The downside to domesticated animals, however, is that as people lived in closer proximity to animals and other humans, waste disposal became more difficult, and the diseases endemic in animal populations to were able to make the jump to humans.[46]

The effects of the Agricultural Revolution were not limited to cultivation, but extended to many interconnected aspects of Neolithic society. Since agriculture allowed humans to settle down in one area, they needed more permanent structures in which to live. Settlement led to new types of architecture. Some of the earliest structures found in the archeological record are mud huts. Located in various parts of Southwest Asia, mud huts were made of mud bricks and plaster, an amalgam of lime with sand and water that is spread on walls and ceilings and creates a smooth surface when dried.[47] These huts were painted with images of Neolithic life, giving archaeologists and historians a view into early Neolithic societies.

In addition to mud huts, archeologists have discovered the existence of Neolithic stilt houses, which are houses raised on piles above water, serving as a protection against rodents and flooding. Pit-houses, shelters that are partly dug into the ground and covered by a thatched roof, were used for both housing and food storage.[48] Over time, Neolithic settlements grew in size, and homes were built with lumber and stone.[49] Eventually, farming villages would develop around these permanent structures, and their use expanded to ceremonial and governmental functions.

As Neolithic societies increased, complex tombs and ritual structures were constructed. While funeral practices existed in the Paleolithic era, these traditions would become more elaborate as populations grew. Collective tombs, such as long barrows, held many bodies in an accessible place, likely so that bones could be utilized in ancestral worship (fig. 9).[50]

Figure 9: Stoney Littleton Long Barrow, circa 3500 BCE. Photograph by Mike Peel. Somerset, England (public domain).

Those with higher social status were buried in chamber tombs, which were built with rock or wood and often contained material possessions or the remains of attendants.[51]

The most striking of the Neolithic tombs are the megaliths. Megaliths are upright stone slabs with a horizontal capstone slab on top that were used to mark graves and to serve as a ceremonial space.[52] One of the oldest examples of this kind of structure is Göbekli Tepe, which dates back to 9000 BCE. Historians believe this site was used as a religious temple.[53] Another remarkable example of a megalith is Stonehenge, located in southwest England (fig. 10).

Figure 10: Stonehenge, circa 3100–1500 BCE.Wiltshire, England (public domain).

Stonehenge was constructed in different phases between 3100 BCE and 1500 BCE, and its construction required the labor of at least 10,000 people.[54] Excavations to date reveal cremated remains of more than fifty people, making it the largest known Neolithic burial site. Historians debate how Stonehenge was constructed, but most theories rest on the notion that large stones were dragged across the ground on tracks made of timber, rope, and perhaps even glacier ice. The stones were likely lifted with wooden A-frames and rope. For the people of the Salisbury Plain of what is England today, Stonehenge functioned as a ceremonial center and astronomical observatory.[55] The monument tracks the movements of the sun and the moon, demonstrating a basic understanding of the connections between astronomical events and seasonal changes.

As Neolithic villages grew in population and size, they began to create surpluses of food and other goods. These excesses allfowed trade with neighboring villages. Trade created the need to record and track economic information more effectively, and also influenced how these societies divided their labor. These changes led to the birth of civilizations, which are societies with complex social, political, and economic organizational structures, generally with defined borders and systems of writing and government. The earliest civilization was Sumer, located in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq).[56] Sumer was established as early as 5500 BCE, and other civilizations developed independently around the globe: Egypt around 3500 BCE, Crete around 2500 BCE, the Indus Valley around 2300 BCE, and northern China around 2200 BCE.[57] These ancient civilizations would create writing, metallurgy, laws, and warfare, taking human endeavors out of the context of prehistory and into the realm of recorded history.

[1] Gloria Fiero, The Humanistic Tradition: Prehistory to the Early Modern World (New York: McGraw Hill Education, 2015), 2.

[2] Stephen Morillo, Frameworks of World History: Networks, Hierarchies, Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 8.

[3] Morillo, Frameworks of World History.

[4] Morillo, Frameworks of World History.

[5] James McClellan and Harold Dorn, Science and Technology in World History: An Introduction (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006), 6.

[6] McClellan and Dorn, Science and Technology, 7.

[7] Morillo, Frameworks of World History, 10.

[8] McClellan and Dorn, Science and Technology, 8.

[9] Morillo, Frameworks of World History, 11.

[10] Morillo, Frameworks of World History.

[11] McClellan and Dorn, Science and Technology, 9.

[12] McClellan and Dorn, Science and Technology, 9.

[13] Matt Kaplan, “Stone Tools Shed Light on Early Human Migrations,” Nature, August 31, 2011.

[14] Emma Pomeroy et al., “New Neanderthal Remains Associated with the ‘Flower Burial’ at Shanidar Cave,” Antiquity 94, 373 (2020): 12–14.

[15] Steven Mithen, The Singing Neanderthals: The Origins of Music, Language, Mind, and Body (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007), 105.

[16] Peter Ulric Tse, “Symbolic Thought and the Evolution of Human Morality,” in The Evolution of Morality: Adaptations and Innateness, ed. Walter Sinnott-Armstrong and Christian B. Miller, vol. 1 of Moral Psychology (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2008), 269.

[17] Morillo, Frameworks of World History, 14.

[18] Morillo, Frameworks of World History, 14.

[19] Morillo, Frameworks of World History, 14. 18.

[20] Fiero, The Humanistic Tradition, 3.

[21] Morillo, Frameworks of World History, 22.

[22] Morillo, Frameworks of World History.

[23] Robert J. Wenke and Deborah I. Olszewski, Patterns in Prehistory: Humankind’s First Three Million Years (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 113.

[24] Wenke and Olszewski, Patterns in Prehistory, 126.

[25] Alexander Marshack, “Lunar Notation on Upper Paleolithic Remains,” Science 146, no. 3645 (1964): 744.

[26] Marshack, “Lunar Notation on Upper Paleolithic Remains,” 6.

[27] McClellan and Dorn, Science and Technology, 14.

[28] Dani Nadel, “Stone Age Hut in Israel Yields World’s Oldest Evidence of Bedding,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 101, no. 17 (2004): 6822.

[29] Nadel, “Stone Age Hut in Israel Yields World’s Oldest Evidence of Bedding,” 6823.

[30] Wenke and Olszewski, Patterns in Prehistory, 138.

[31] Wenke and Olszewski, Patterns in Prehistory, 175.

[32] Bryan Bunch and Alexander Hellemans, The History of Science and Technology (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004), 14–15.

[33] Bunch and Hellemans, The History of Science and Technology.

[34] Fiero, The Humanistic Tradition, 4.

[35] Fiero, The Humanistic Tradition, 4.

[36] Fiero, The Humanistic Tradition, 5.

[37] Wenke and Olszewski, Patterns in Prehistory, 240.

[38] McClellan and Dorn, Science and Technology, 17.

[39] Wenke and Olszewski, Patterns in Prehistory, 229.

[40] Wenke and Olszewski, Patterns in Prehistory, 229.

[41] McClellan and Dorn, Science and Technology, 18.

[42] Bunch and Hellemans, History of Science and Technology, 55.

[43] Wenke and Olszewski, Patterns in Prehistory, 60.

[44] Graeme Barker, The Agricultural Revolution in Prehistory: Why Did Foragers Become Farmers? (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 69–88.

[45] David Grimm, “Dogs May Have Been Domesticated More Than Once,” Science 352, no. 6290 (2016): 1153.

[46] Morillo, Frameworks of World History, 49.

[47] Fiero, The Humanistic Tradition, 6.

[48] Bunch and Hellemans, History of Science and Technology, 20.

[49] Wenke and Olszewski, Patterns in Prehistory, 294.

[50] Wenke and Olszewski, Patterns in Prehistory, 295.

[51] Wenke and Olszewski, Patterns in Prehistory, 295.

[52] Fiero, The Humanistic Tradition, 8.

[53] Andrew Curry, “Göbekli Tepe: The World’s First Temple?” Smithsonian Magazine, November 2008.

[54] McClellan and Dorn, Science and Technology, 24.

[55] McClellan and Dorn, Science and Technology, 27.

[56] Fiero, The Humanistic Tradition, 9.

[57] Fiero, The Humanistic Tradition, 9.

Further Reading

Primary Sources:

Adze. Artifact. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Bone needle. Photograph by Didier Descouens. Haute-Garonne, France.

Cave painting. Photograph by John McLinden. Lascaux Caves, France.

Neanderthal burial. Photograph by Carol Tomylees. Natural History Museum, London.

Pot. Artifact. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Simple chopper. Photograph by Didier Descouens. Muséum de Toulouse, France.

Skull of Australopithecus Afarensis. Photograph by Tiia Monto. Naturmuseum Augsburg, Germany.

Stonehenge. Monument. Wiltshire, England.

Stoney Littleton Long Barrow. Photograph by Mike Peel. Somerset, England.

Venus of Willendorf. Photograph by Artúr Herczeg. Vienna Museum of Natural History, Austria.

Secondary Sources:

Barker, Graeme. The Agricultural Revolution in Prehistory: Why Did Foragers Become Farmers? New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Bunch, Bryan, and Alexander Hellemans. The History of Science and Technology. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004.

Curry, Andrew. “Göbekli Tepe: The World’s First Temple?,” Smithsonian Magazine, November 2008.

Fiero, Gloria. The Humanistic Tradition: Prehistory to the Early Modern World. New York: McGraw Hill Education, 2015.

Grimm, David. “Dogs May Have Been Domesticated More Than Once.” Science 352, no. 6290 (2016): 1153–54.

Kaplan, Matt. “Stone Tools Shed Light on Early Human Migrations.” Nature, August 31, 2011.

McClellan, James, and Harold Dorn. Science and Technology in World History: An Introduction. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

Marshack, Alexander. “Lunar Notation on Upper Paleolithic Remains.” Science 146, no. 3645 (1964): 743–45.

Mithen, Steven. The Singing Neanderthals: The Origins of Music, Language, Mind, and Body. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007.

Morillo, Stephen. Frameworks of World History: Networks, Hierarchies, Culture. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Nadel, Dani. “Stone Age Hut in Israel Yields World’s Oldest Evidence of Bedding.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 101, no. 17 (2004): 6822–26.

Pomeroy, Emma, et al. “New Neanderthal Remains Associated with the ‘Flower Burial’ at Shanidar Cave.” Antiquity 94, 373 (2020): 11–26.

Tse, Peter Ulric. “Symbolic Thought and the Evolution of Human Morality.” In The Evolution of Morality: Adaptations and Innateness, edited by Walter Sinnott-Armstrong and Christian B. Miller, vol. 1 of Moral Psychology. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2008.

Wenke, Robert J., and Deborah I. Olszewski. Patterns in Prehistory: Humankind’s First Three Million Years. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.