Stephanie Guerin-Yodice

King Hammurabi of Babylon: circa 1795 to 1750 BCE

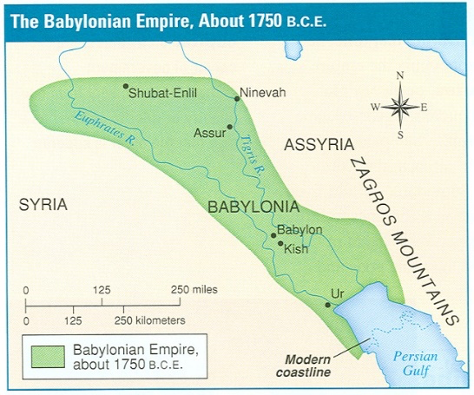

Hammurabi was the sixth king of the Amorite Dynasty (2400 BCE to 1595 BCE). He established the city of Babylon as the capital during his reign. Like rulers before him, he slowly encroached on the surrounding regions through war and force, but he is also notable for his use of diplomacy. Hammurabi judiciously elevated Marduk, the god of fertility and the original god of thunderstorms, as the chief deity of Babylon. Marduk came to be synonymous with the god Ashur, who was chief deity in the Mesopotamian pantheon of gods and goddesses up until Hammurabi’s reign. By establishing a new deity, Hammurabi was also able to issue a set of laws in which he claimed to come from the divine word of Marduk himself.

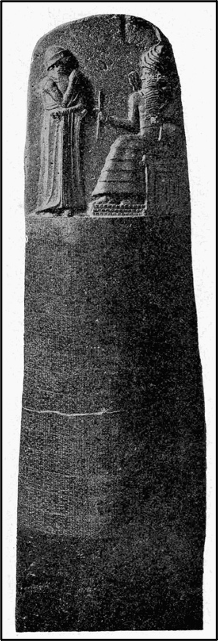

In 1901, archeologists discovered a large basalt stele, 7.4 feet tall and covered in cuneiform writing. At the top of the stele, Hammurabi is standing in front of the seated Marduk, engaged in what appears to be a conversation, and below the two figures, epigraphists were able to decipher almost 300 laws. Hammurabi’s innovative code of law indicates the transitional nature of his society because he standardized a set of rules that laid the foundation for advanced forms of governance. Hammurabi erected a stele or tablet within each city-state to regulate the daily lives of its occupants and make people aware of the punishments that would be exacted if the rules were broken.

Hammurabi took Sargon’s consolidation a step further by unifying a set of laws that each city-state within the Babylonian territory had to follow and setting in stone the action to be taken if the laws were broken.[1] Additionally, Hammurabi’s cunning use of Marduk’s authority as chief god allowed him to depict himself as a benevolent, divine authority. He also ensured that he was not himself directly responsible for enforcing punishment if the laws were broken, as they were really dictated by Marduk. From this centralized code of law, historians and cultural anthropologists have gained insight into the daily lives of people in ancient Mesopotamia and the challenges their societies faced.

While the registers display the same set of laws, punishments were different for property owners, freed men, and slaves. Laying the foundation for modern judicial reasoning, Hammurabi’s laws addressed issues such as property, theft, trade, contracts, resources, and family matters. They also demonstrated Hammurabi’s vision for a collectivized community of people who were forced to share responsibility: not just for their own actions, but for the actions of others. One law, for instance, highlights the importance of truth, “If any one bring an accusation of any crime before the elders, and does not prove what he has charged, he shall, if it be a capital offense charged, be put to death.”[2] Another law regarding theft also demonstrates that punishments were determined by an individual’s social class: “If any one steal cattle or sheep, or an ass, or a pig or a goat, if it belong to a god or to the court, the thief shall pay thirtyfold therefor; if they belonged to a freed man of the king he shall pay tenfold; if the thief has nothing with which to pay he shall be put to death.” [3]

Concerning slaves, the law stated, “If anyone find runaway male or female slaves in the open country and bring them to their masters, the master of the slaves shall pay him two shekels of silver… If he hold the slaves in his house, and they are caught there, he shall be put to death… If the slave that he caught run away from him, then shall he swear to the owners of the slave, and he is free of all blame.”[4] These law codes and many others demonstrate the need to enforce order among the people, but the punishment was administered based on social class distinctions.

Hammurabi’s code of law represents an amalgamation of technology and epistemological knowledge that fused traditional behavior, religious authority, and political conformity into a body of law that predates the Old Testament. Introducing the principle of lex talionis (an eye for an eye) into the process of nation-building, Hammurabi managed to solidify his position as one of the great leaders of ancient Mesopotamia. Swift and clear punishment proved to be an efficient means of regulating the behavior of the masses, allowing Hammurabi to control more important elements of state-building, such as bureaucratic efficiency, territorial expansion, and economic prosperity.

[1] In the 3rd Dynasty of Ur the King Ur-Nammu constructed a basic set of laws that were the precursor to Hammurabi’s Codes. See A Library of Knowledge of the Cuneiform Digital Library: http://cdli.ox.ac.uk/wiki/doku.php?id=laws_ur_nammu

[2]. “Ancient History Sourcebook: Code of Hammurabi, c. 1780 BCE, ” Internet History Sourcebooks, https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/ancient/hamcode.asp#horne.

[3]. Code of Hammurabi.

[4]. Code of Hammurabi.