Jennie Brosnan

What are Doing History segments?

Women doctors, especially those practicing in the mid to late nineteenth century, played a large role in disseminating information to the public about hygiene and sanitation, as well as being involved in political debate surrounding the female body during the 1860s to 1880s. By examining letters, we can discern much about early networks among women doctors. As you read this Doing History segment, think about how primary sources shape and reshape our understanding of the past.

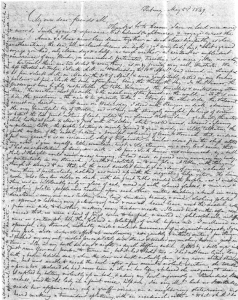

The following letter is an example of many that Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell (See below.) sent to her family in Cincinnati after moving to New York in 1849 to establish her own medical practice. (Click on the image to enlarge.) As can be seen from this letter, the writing is small and fills the whole page, including writing in the margins.

This indicates that while Blackwell had much to say about her experiences in New York, she was also short of money. Paper was expensive during the nineteenth century and it was common practice to use all the available space on the page.

This indicates that while Blackwell had much to say about her experiences in New York, she was also short of money. Paper was expensive during the nineteenth century and it was common practice to use all the available space on the page.

When researching the topic of female medical networks, a number of different areas of history need to be considered. Not only is this a cross-section of gender history and the history of medicine, but the construction of Victorian society and network theory also have a part. This section will look at the development of the female medical network and the implications this had for modern medicine, including the advent of modern birth control. But first, a basic background on the foundational Elizabeth Blackwell will be useful.

A Brief Biography of Elizabeth Blackwell

Elizabeth Blackwell was the first female doctor to graduate with a medical degree. As such, she is an important figure in the history of medicine, especially since she was influential for the path of women doctors on both sides of the Atlantic.

Blackwell, having graduating in 1849 from Geneva College, New York, gained work experience during 1850 and 1851 at La Maternité in Paris and St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London. There, she reveled in her celebrity as the first female doctor and was welcomed with open arms, principally by the middle and upper classes of London society. One particular group who received Blackwell in London was the “Langham Place Circle;” there, she cemented a network of supportive, financially secure, independently-minded women -or “Lady Bountifuls” –including Lady Byron, Barbara Leigh Smith and the Comtesse de Noailles, . Although these women were not particularly well-educated, they had access to money and connections both in Britain and abroad.

Upon Blackwell’s return to New York in 1851, however, she found herself alone. While she still enjoyed letters of support and advice from the “Lady Bountifuls,” she also often received hostile letters. She had to fend off unwanted male attention on her walks home from various patients’ houses late at night. She struggled to establish herself in New York as a mainstream doctor, and to dispel rumors that she was an abortionist. She found herself isolated in her profession.

For more on Blackwell, see the National Library of Medicine: Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell

Female Medical Networks

Elizabeth Blackwell put her medical degree to good use by founding medical schools in both New York and London, becoming the first woman to be on the General Medical Register in Britain in 1858 and publishing several books. She was at the heart of many campaigns to educate the public about ‘moral hygiene’ which can be seen as her own brand of sex education, as well as basic hygiene and sanitation. As the first female doctor, Blackwell is the starting point for female medical networks during the nineteenth century as she mentored and taught many of the first women to practice medicine in both Britain and America

Challenges for women trying to break into the medical field were so great that the first generation of female doctors, both in Britain and America, formed networks consisting solely of other women as a means of financial, social and political support. (For example, groups such as the Langham Place Circle, based in London, provided the financial means for Elizabeth Blackwell to establish the New York Infirmary for Women and Children in 1857.) But the relationships within these female medical networks were often fraught and frequently competitive, especially as these women banded together out of necessity: they were in a predominately male environment which was worlds away from the female dominated private sphere they otherwise would have been familiar with, such as the Victorian home and the homes of families they visited.

Biographers of nineteenth-century female doctors have tended to associate these networks with friendship, and, certainly, relationships of a significant length blurred the lines of professionalism and friendship. But the equation of female relationship with friendship is highly gendered and factually incorrect. While it is necessary to highlight that many of the relationships within the female medical network were amicable, many were also strictly professional—just as they would have been with male professionals. Until recently, scholars have belittled these female networks while seeing male networks as legitimate and more tangible.

There were a number of issues the female medical networks faced:

- The relationship that existed within the male-dominated field of medicine and the women who dared to challenge the medical establishment was complex.

- The connections between medical women who struggled to find common ground whilst maintaining a united front was often fraught.

- The groups of respectable middle and upper class women who came together to provide financial support for women in medicine took serious risks by associating themselves with the women who existed on the fringes of the medical establishment.

There are other reasons as to why the female medical network was problematic: the first was competition. Excluded from the standard systems of mentorship and apprenticeship, these women wanted to shine individually—they did not want to share their accomplishments with other women who were also emerging in their field. Nor did they want to share the limelight with others; each had her own agenda. The second reason is that, being first women in their field, these women had no system of mentoring or apprenticeship to avail themselves of; they didn’t understand how profession relationships worked. Men who wished to pursue medicine did so under a system of apprenticeship, often ‘walking the wards’ at hospitals, under the guidance of senior doctors and flourished accordingly. For women, the only way for them to gain experience or gainful employment was to set up their own dispensary.

It is clear from the work of Roy Porter that pioneer women were unable to partake in the kind of fostering activities in their early careers that their male counterparts enjoyed because of the misogynistic attitudes surrounding the patriarchal society they worked in. The atmosphere within medicine at this time was equal to a “fraternity”, thus making it nearly impossible for a woman to break into the ranks.

Finally, not all relationships within the female medical network were amicable. For example, Elizabeth Blackwell and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson clashed on the Contagious Diseases Acts, as well as on a number of other medical issues. These acts, in place between 1864 and 1884, sought to regulate prostitution and venereal disease within Britain and its empire by calling for the forced gynecological examination of women suspected of being prostitutes.

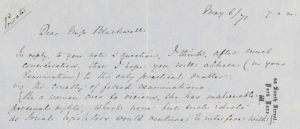

Blackwell had been Garrett Anderson’s mentor. But while Anderson chose to side with the mainstream stance of the medical profession and backed the acts, Blackwell did not. Instead, Blackwell joined another network consisting of the Ladies’ National Association for the Repeal of the Contagious Disease Acts. This letter from Florence Nightingale to Elizabeth Blackwell, 6th May 1871, discusses the issue of ‘forced examination’. (Click on the image to enlarge.)

While there are no existing letters of the conflict between Blackwell and Garrett Anderson, it has been well-documented by biographers of both women, as well as other secondary sources on the history of women in medicine.

While there are no existing letters of the conflict between Blackwell and Garrett Anderson, it has been well-documented by biographers of both women, as well as other secondary sources on the history of women in medicine.

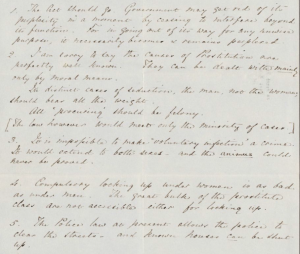

Of course, there is plenty of evidence that suggests that many women in medicine did provide support for one another, as well. For example, Florence Nightingale and Blackwell also discussed the government policy on the Contagious Diseases Acts and agreed as to the implications these laws had for women suspected of being prostitutes. In other correspondence the two medical women discussed the infection rates for soldiers with syphilis and the impact this had on the ability of the British army to carry out their duties. As explored in the following letter, Nightingale and Blackwell contemplated many options as alternatives to the Contagious Diseases Acts, and sought their repeal. (Click on the image to enlarge.)

Medical Women’s Impact on Hygiene and Sanitation

Medical Women’s Impact on Hygiene and Sanitation

These women doctors were highly involved with developing hygiene and sanitation reform. For example, Elizabeth Blackwell founded the National Health Society in 1871 as a means of communicating knowledge about sanitation and hygiene to the lower classes through lectures and classes. In America and Britain, the establishment of female-led medical schools for women doctors helped develop further female medical networks and elevated the position of the woman doctor in the medical profession. Medical Women were involved in a series of public health campaigns throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The Contagious Diseases Acts, mentioned earlier, were a prime example of the role female doctors played in shifting public health policy. Elizabeth Blackwell later called on women doctors in the empire to continue their work in campaigning against the Contagious Diseases Acts, as well as providing excellent medical care to infected women, long after the legislation had been repealed in Britain.

The well-educated, capable female doctors trained by women’s medical schools, such as the London School of Medicine for Women, played an important role in the First and Second World Wars, helping to develop and establish the woman doctor’s place within medicine.

Advent and Impact of Modern Birth Control

The nineteenth century brought about new advances in the development of modern birth control, as well. The vulcanization of rubber in 1839 during the industrial era brought the condom as a viable method of contraception for men; family limitation and sexual health manuals introduced women to a new world of contraceptive measures. Texts like Richard Carlile’s Every Woman’s Book; or What is Love? Containing Most Important Instructions for the Prudent Regulation of the Principle of Love and the Number of the Family in 1826 described methods of birth prevention including the withdrawal method, the use of the ‘sponge’ for women and the use of the ‘glove’ for men.

The Neo-Malthusians, inspired by the economic theorist Thomas Malthus who favored population control, advocated the use of such measures. The beliefs of Neo-Malthusianism in the mid to late nineteenth century were loosely based on Thomas Malthus’ Essay on the Principle of Population (1798). Malthus, an economic theorist, advocated the use of moral restraint as a means of controlling the population, preventing starvation and unrest. The Neo-Malthusian movement, later called the Malthusian League, was founded in 1877 by C.R. Drysdale. Even though the Neo-Malthusians adapted the name of Malthus, he did not advocate the use of artificial contraception in his writings. Instead, Malthus believed that late marriage and abstinence were the means to population control. Two prominent Neo-Malthusians, Annie Besant and Charles Bradlaugh, were arrested for the publication and distribution of Charles Knowlton’s Fruits of Philosophy which followed in the same vein as Richard Carlile’s text describing methods to avoid conception.

This slow but steady advent of contraception provided women with the opportunity to limit their family size and eventually pursue careers of their own.

Further Reading

Bashford, Alison, and Joyce E. Chaplin. The New Worlds of Thomas Robert Malthus: Rereading the Principle of Population. Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2016.

Boyd, Julia. The Excellent Doctor Blackwell: The Life of the First Female Physician. London: Sutton Publishing, 2005.

Caine, Barbara. “Feminism in London circa 1850–1914.” Journal of Urban History 27, no. 6 (2001): 765–78.

Freedman, Estelle. “Separatism as Strategy: Female Institution Building and American Feminism, 1870–1930.” Feminist Studies 5, no. 3 (1979): 512–29.

Garton, Stephen. Histories of Sexuality: Antiquity to Sexual Revolution. London: Equinox, 2004.

Hall, Lesley. Sex, Gender and Social Change in Britain Since 1880. London: Macmillan Press, 2000.

Hurren, Elizabeth. Dying for Victorian Medicine: English Anatomy and Its Trade in the Dead Poor, c. 1834–1929. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

Levine, Philippa. “Love, Friendship and Feminism in Later 19th-Century England.” Women’s Studies International Forum 13, no. 12 (1990): 64.

Manton, Jo. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson. London: Metheun, 1965.

Newman, Charles. The Evolution of Medical Education in the Nineteenth Century. London: Oxford University Press, 1957.

Porter, Roy. Blood and Guts: A Short History of Medicine. London: Penguin Books, 2002.

Riznik, Barnes. “The Professional Lives of Early Nineteenth-Century New England Doctors.” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 19, no. 1 (1964): 1–16.

Sherrod, Drury. “The Bonds of Men: Problems and Possibilities in Close Male Relationships,” in The Making of Masculinities: The New Men’s Studies, ed. Harry Brod. London: Unwin Hyman Ltd., 1987, pp. 213–40.