Antoine Leveque

In the second half of the eighteenth century, European naturalists started to see the physical diversity of people around the globe differently. More than was previously the case, evolving epistemologies tended to consign a much broader range of accounts, and especially traveler’s tales, to the realm of “fable.” Such was, for instance, the case of accounts telling of giants living in Patagonia or of people with tails. In the 1750s, two naturalists had an impact on the development of theories pertaining to the variability of the human species. Swedish taxonomist Karl Linnaeus (1707–1778) coined the term homo sapiens and, in light of comparative anatomy, was the first to include humankind into the order of primates. He divided mankind into five groups: American, European, Asian, African, and one labelled as “deformed by climate or art.” French zoologist, botanist, and philosopher Louis Leclerc de Buffon (1707–1788) initiated the natural history of man and disseminated a radically new meaning for the concept of species.[1]

In time, the project of first subclassifying human types and then discovering the reasons accounting for intraspecific variability would upset pre-Enlightenment theories about the station of humankind within the natural order. In 1859, British naturalist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) published On the Origin of Species and French biologist Paul Broca (1824–1880) established the world’s first anthropological society. This year may be used to mark the date of final exclusion of a concept known as the Great Chain of Being from scientific literature.[2] According to this concept, nature was God’s creation and he had placed the human form atop all other lifeforms by giving it a common form, or “essence,” residing in the ability to reflect divine intellect.

As ethnology and anthropology became institutional sciences, this worldview, which considered the specificity of the human form as an intentional act of God, would be overturned.[3] The world’s first ethnological society was founded in Paris in the 1830s under the patronage of François d’Orléans, Prince of Joinville (1818–1900), who was a hero in the colonial war that France waged in North Africa.[4] Ethnology was then defined as the scientific study of human races and the concept of race[5] crystalized as a paradigm in this discipline.[6] The Ethnological Society of Paris was founded by William F. Edwards (1777–1842), whose family owned slaves in Jamaica when the British crown abolished slavery.[7] The world’s leading practitioner of anthropology in the second half of the nineteenth century, Paul Broca, credited Edwards for having first stated the scientific objective of his newly institutionalized discipline.[8]

In the second half of the eighteenth century, scholars focusing on the natural history of man often used the concept of variety instead of the concept of race to conduct their research.[9] Yet European explorers and colonialists were still in the process of finishing their survey of the world and of the people inhabiting it as European nations started to administer large-scale colonial empires. This is when the concept of race started to become central in scientific circles. The period ranging from 1750 to 1900 was marked by a profound change of ideas pertaining to the trading of African slaves, whom European colonists had been using as free labor to maximize financial profits.[10] The scientific study of physical differences became a way to legitimize differences pertaining to the legal status of people who had European ancestry and people who did not.

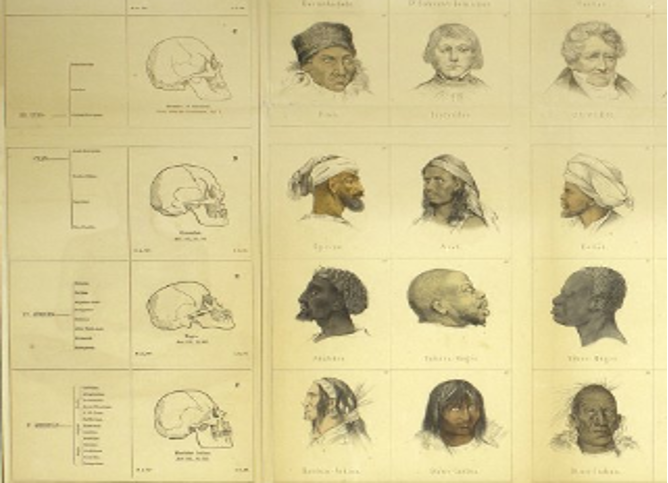

Figure 1. Specimens of human races. Illustration by Peter Kramer, “Ethnographic Tableau: Specimens of Various Races of Mankind” in J. C. Nott. and George R. Gliddon, Indigenous Races of the Earth; or, New Chapters of Ethnological Inquiry (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1857).

Johannes F. Blumenbach (1752–1840) coined the term “Caucasian” and started a seminal study of human skulls, which he deemed representative of each human variety. Using this work, later generations of craniologists would produce theories in which the cranial structures of individual people were typified according to each race. Yet there has never been complete agreement among ethnologists and anthropologists about the exact number of human races or about the precise criteria to distinguish one race from the next. However, throughout the nineteenth century, European naturalists interested in the natural history of man were divided into two camps: those embracing a monogenetic theory of human variability and those embracing a polygenetic one.

In the 1820s, the polygenetic theory, which stated that there were originally different and permanent types, races, or species within mankind, became prevalent in France.[11] This perspective was highly unorthodox because it contradicted the revealed truth of the Bible, which stated that all of mankind descended from a single pair of humans, Adam and Eve. Theories upholding the unity of the human species were called “monogenetic,” but did not uphold a more egalitarian view of the races’ intellectual abilities than “polygenetic” theories. Indeed, nineteenth-century ethnologists and anthropologists recognized the existence of natural differences with regard to the intellectual abilities of the human races they distinguished taxonomically. In the late eighteenth century, European physiologists started to correlate the study of racial types with physiological investigations about the intellect, increasingly consensually considered as the function of an organ. They thought that racial differences entailed specific cranial structures and thus specific mental abilities. Anthropology considered itself useful as a science to ground political decisions because it revealed the physiological specificity of people and thus the function that was best suited to them.

In the second part of the nineteenth century, anthropology was not only the science in charge of researching the taxonomical lines between human races, it also tried to decipher the connection between bone structure and behavior.[12] Physical anthropology applied not only to human races but also to differences between the sexes and political ‘classes’.[13] It was a way to use the natural sciences in order to justify political inequalities. Between 1830 and 1870, ethnology and anthropology were founded as institutional disciplines in all the countries of Western Europe and in the United States of America. As sciences, they sought to establish the nature of the cause-and-effect relationship between the biological makeup of the human races and their historical development. The use of comparative anatomy for taxonomical purposes had started in the late eighteenth century, and, at this time, authors could still classify great apes among humans.[14]

The classification of bones according to their sizes was seemingly neutral and objective: it allowed ethnology and anthropology to gain the repute of being able to solve conflicts of interest impartially. People of different geographical ancestry coexisted in the colonies established by Europeans, and the scientific status of ethnology gave the white race a powerful rhetorical tool to argue that nonwhites were physiologically unfit for political life. For instance, the physician Josiah Nott (1804–1873), based in Mobile, Alabama, fought to preserve the legal right of whites to own African slaves: he was eager to spread the findings of French and British ethnological science in the United States.[15] Paul Broca measured 180,000 human skulls in an attempt to establish racial classifications and made discoveries pertaining to the localization of brain functions. However, his work did not create a precedent for the discipline that is called anthropology today. Nowadays, anthropology is typically defined as “the study of people, culture and society through all time and everywhere around the world.”[16]

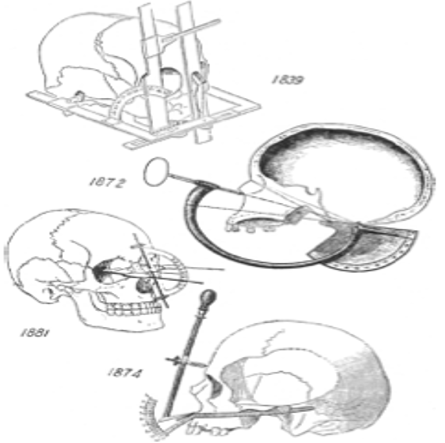

Figure 2. Anthropological instruments used for measuring human skulls. Lucile E. Hoyme, “Physical Anthropology and Its Instruments: An Historical Study,” in Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 9, no. 4 (Winter 1953): 416.

[1]. Ernst Mayr, The Growth of Biological Thought (Harvard: Harvard University Press, 1982), 260–63.

[2]. This notion had been continuously prevalent in the discourse of European scholars since Greco-Roman antiquity and through the Middle Ages, as well as during the Enlightenment and modern period. Michael Ruse, Monad to Man: The Concept of Progress in Evolutionary Biology (Harvard: Harvard University Press, 1996), 21–23.

[3]. Jennifer Michael Hecht, The End of the Soul: Scientific Modernity, Atheism, and Anthropology in France (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005).

| [4]. M. Alfred Nettement, Histoire de la conquête d’Alger: écrite sur des documents inédits et authentiques(Paris: J. Lecoffre, 1870), 207-08. |

[5]. The term “race” has a long history in the Romance languages: it started to be used in the vocabulary of animal and plant breeders in the 15th century, before French royal and noble families started to use it in the sixteenth and seventeenth century. Historians generally agree that the contemporary meaning of the term was first used in a scientific theory in 1684. This date marks the first occurrence in science of the idea that there is a natural division among people according to their geographical ancestry. The new use of the term conveyed the notion that physical differences are worth correlating with people’s geographical ancestry. However, scientific interest for this topic remained marginal until the 1780s. See Siep Stuurman, “François Bernier and the Invention of Racial Classification,” History Workshop Journal 50, no. 1, (2000): 1–21, https://doi.org/10.1093/hwj/2000.50.1.

[6]. Robert Rondinelli, “An Historical Review of Racial Studies in Physical Anthropology from a Kuhnian Perspective, ” Steward Anthropological Society Journal 6, no. 1 (Fall 1974): 49–69, 56.

[7]. Frank Spencer, ed., History of Physical Anthropology: An Encyclopedia, vol. 2 (New-York: Garland Publishing, 1997), 357–59.

[8]. Claude Blanckaert, De la race à l’évolution, Paul Broca et l’anthropologie française (Paris: Harmattan, 2009).

[9]. Nancy Stepan, The Idea of Race in Science: Great Britain, 1800–1960 (Hamden, CT: Archon Books, 1982).

[10]. In 1750, this commercial practice had reached its apex, but it was definitively abolished in England, France, and the United States by the time that the nineteenth century came to a close. Pierre Boulle, “In Defense of Slavery: Origins of a Racist Ideology in France,” in History from Below, Studies in Popular Protest and Popular Ideology, Frederick Krantz, ed. (Oxford: B. Blackwell, 1988), 220–24.

[11]. Martin S. Staum, Labelling People: French Scholars on Race, Society, and Empire, 1815–1848 (New York : McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2003).

[12]. John W. Stocking, Jr., Bones, Bodies, Behavior: Essays on Biological Anthropology, History of Anthropology, vol. 5 (Madison: Wisconsin University Press, 1988).

[13]. Londa L. Schiebinger, Nature’s Body: Gender in the Making of Modern Science (Boston: Beacon Press, 1993).

[14]. James Burnet, Lord Monboddo, Orangutans and the Origins of Human Nature (Bristol: Thoemmes Press, 2000).

[15]. Josiah Clark Nott, Two Lectures on the Natural History of the Caucasian and Negro Races (New York: Barlett and Welford, 1849), 7–8.

[16]. James H. Birx, Encyclopedia of Anthropology, vol. 1 (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2005), 142. (Italics added.)