Tashia Dare

What is Coptic?

The modern term “Copt” derives from a corruption of the ancient Greek aigyptos via Arabic qibt, meaning “Egyptian.” This is a reference to native Egyptians as opposed to Greek and Roman settlers. The Coptic period (or Byzantine period) began with the division of the Roman Empire in 395 CE and lasted until 641 CE when the Byzantine Empire was defeated through the Arab conquest.[1] This era belongs to the late Roman or Byzantine Empire through the Arab conquest under the Umayyad, Abbasid, and Fatimid caliphates.[2] During this time Coptic, the Egyptian language that was written using both the Greek alphabet and Demotic (a common form of Egyptian writing), was the lingua franca.

Copt also references the native Egyptian Christian population. Christianity arrived in Egypt during the first century CE, and by the fourth century the region was largely Christianized. After the Arab conquest, and despite periods of persecution by Muslims, Copts were viewed as the intellectual elite and held important positions. However, due to heavy taxation of non-Muslims, many Coptic Christians converted to Islam. In subsequent centuries many more Egyptians became Muslim, resulting in only 10 percent of today’s Egyptian population calling themselves Coptic.

Additionally, the term describes an artistic movement that developed as early as the late third century CE and continued until the twelfth century, when the arts and crafts of Egyptian Christians were no longer produced because the artists were by then largely copying Byzantine and Islamic art.[3] Artistically, the term encompasses both pagan art as well as early and medieval Egyptian Christian art. Iconography found in Coptic textiles includes the ancient Egyptian ankh (for the sign of the cross); Greco-Roman motifs such as nereids, gods and goddesses, putti, dancers, animals, and vegetation; Christian images of Biblical figures, saints, and other depictions of the Church; Persian/Sassanian motifs of birds and other animals, rosettes, and trees; and Islamic non-figural designs and inscriptions.

The majority of the textiles we have today were found in Middle Egypt, primarily in Antinoöpolis/Antinoë (modern Sheikh Abada); Panopolis (modern Akhmim); and the Fayum area. These, along with Alexandria, were textile production centers. Many textiles were found in Christian burials. The dry conditions of Egypt helped preserve these delicate fabrics, which were initially made from linen, but later were made from wool, cotton, and eventually—and more rarely—silk.[4] Mummification ceased beginning in the fourth century CE. The general practice was to place a body on wooden planks or on earth rather than in a coffin. Shrouds were kept in place with narrow bandages, imitating earlier mummies. Each shroud covered different parts of the body. The number of wrappings on a body demonstrated the status of the individual. Bodies could be wrapped in tunics, mantles, and furnishing textiles, such as curtains. Furthermore, many had cushions underneath the head, which were often covered with decorated fabrics. The textile wrappings allowed moisture from the body to be gradually drawn out. Wall hangings have also been found in many graves, having previously been kept as heirlooms for years.[5]

Coptic Weaving

Glossary of Weaving Terms

Most Coptic textiles were produced in plain (also known as tabby weave) and tapestry weave techniques using simple looms that were often very wide. Tapestry weave decorations were commonly woven into a basic linen fabric or sometimes sewn onto the linen. This type of weaving allowed the weaver to achieve greater detail than with other techniques, such as highlighting geometric lines or body features of humans and animals and creating variations of outlines. The preservation of selvage in some fragments indicates that the textile was sewn onto linen rather than woven directly into the fabric.

Although tapestry and plain weave were the most common forms of producing textiles, loop weave and sprang, among others, were also employed. Another decorative weave technique was the “flying shuttle.” For this method, thin weft threads, usually light in color, were added during weaving to provide contrast through fine internal lines or patterned details.[6] This technique appears to be unique to Coptic textiles.

Linen has a long history in Egypt, but outside of Egypt wool was the most important clothing material because it was easier to produce, provided more insulation, and accepted dyes more readily. It was only after the Greeks conquered Egypt in the fourth century BCE and selected flocks of sheep were introduced that wool gained acceptance in Egypt. However, linen remained the dominant fabric, and until Christianity was introduced wool was forbidden to be used in burials. Consequently, mummies buried during the Roman period were wrapped solely in linen.[7] By later periods, flax, from which linen is produced, was still widely grown in Egypt, but it remained a specialized crop, which made it more expensive than local coarse wool.

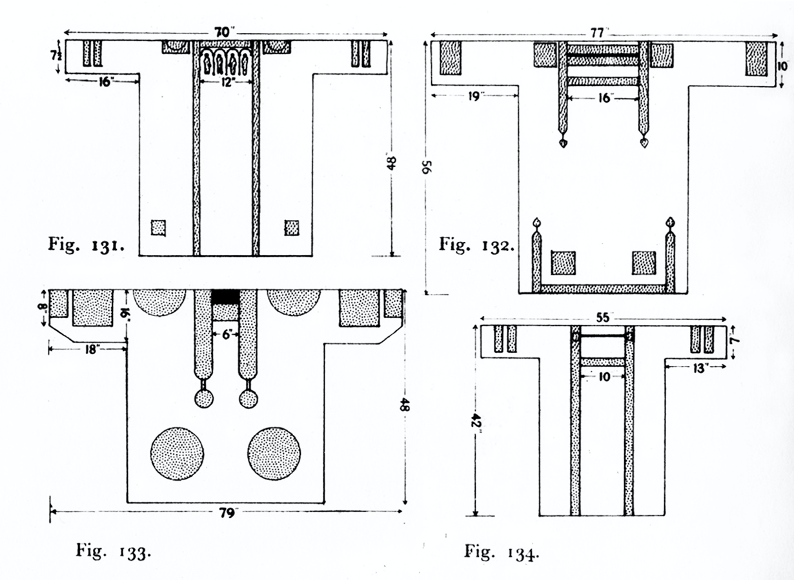

The earliest known examples of Coptic clothing are from circa 300 CE. At the time that Christianity was rapidly spreading in Egypt, clothing for both men and women of different classes began to be more decorative after centuries of having largely been plain. Beginning in the third century, limited areas of patterning were added, which eventually developed into pictorial designs. Sleeveless tunics were replaced with sleeved tunics that included decorative vertical double bands. Clavi, or shoulder stripes, which were initially full-length, now stopped at the waist and had decorative finials (fig. 1).

Figure 1: Diagrams of ornamented tunics. Originally in M. Houston, Ancient Greek, Roman and Byzantine Costume and Decoration (London: A&C Black Publishers, Ltd., 1931). Reproduced in Thelma K. Thomas, “Coptic Byzantine Textiles Found in Egypt: Corpora, Collections, and Scholarly Perspectives,” in Egypt in the Byzantine World, 300–700, edited by Roger S. Bagnall (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 151 . Permission Cambridge University Press.

Over time, ornaments were enlarged and true tapestry weave became progressively significant. Designs were borrowed from traditional tapestry furnishings and became more representational even though they were still mainly monochromatic. Human figures were increasingly consistently depicted within a pictorial scene.[8]

By the sixth century, stylization became prominent and was characteristic of later Coptic textiles. Short, stocky human figures with enlarged eyes are the most notable stylized form. This stylization is due to three possible factors: simplification due to repetition of conventional designs, a reflection of a change in aesthetic tastes, and the growing desire for more elaborate weaves through integration of traditional technique with advanced weaves and repetitive designs.[9]

Persia briefly occupied Egypt in the seventh century and it was then that a Persian/Sassanian influence on Coptic textiles emerged. This notably appears in the form of various motifs, including birds, rosettes, and trees, as well as the outlining of motifs (fig. 2).

Figure 2. Coptic textile fragment with braided cord surround, circa ninth century CE; wool and linen. Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, William Bridges Thayer Memorial, 1928.0129. a,b.

This fragment is representative of Sassanian art. The winged tree in the center is typically Sassanian, as is the symmetry of the birds nesting in the branches and the quadrupeds at the foot of the tree. While the date of this textile is later than the Sassanian dynasty (third to seventh century CE), the artistic style and motifs did not vanish. This is also true of Greco-Roman motifs that continued to be used well into the early Christian era. Later, Islamic styles and motifs would overlap with earlier styles and motifs.

In addition to traditional Coptic tunics and shawls, there were also Persian fitted garments, including outer coats, that had long slender sleeves, were sewn to follow the contour of the torso, and opened down the front.[10] Fitted leggings also went with the outer coat.

Although there were entire silk garments and panels of silk appliquéd onto clothing, silk weaving was generally underdeveloped in Egypt, likely because of the continued significance of the linen industry. Egyptian linen continued to be exported and was highly valued by the Arabs. For finer linen textiles, tapestry bands were woven in, but with colored silk instead of wool.[11] Early Fatimid and Abbasid (tenth through early eleventh centuries) textiles were relatively plain compared to later Fatimid textiles of the late eleventh through twelfth centuries, which had multiple bands of complex decoration. This may reflect the changes in representational art in the early Arab period. During this early period, decoration was typically limited to tiraz (Persian for “embroidery” and for the current ruler or caliph) inscriptions in Kufic lettering. The last definable examples of Coptic textiles are characterized by the use of inscriptions by Christian weavers who were imitating Arabic artists.[12] After this, Coptic textiles and dress become nearly indistinguishable from those of their Arab rulers.

Coptic Dyes

Our knowledge of dyes in Coptic textiles comes, in part, from historical sources. These include two late third/early fourth century CE Egyptian papyri written in Greek concerning dyeing methods. Papyrus X Leidensis includes eleven recipes on dyeing wool, while Papyrus Graecus Holmiensis has seventy instructions on dyeing wool.[13] While colored linens are not common, since linen is resistant to dyeing, wool and cotton easily accept and retain color. Colors were produced from a variety of natural dyestuffs. Blues were achieved using indigo or woad (a yellow cabbage-like plant indigenous to Southeast Europe and Central Asia); yellows from saffron, pomegranate, safflower, or weld (originally from the Mediterranean and West Asia); reds from madder root (Southeast Europe, Southwest Asia, and the Mediterranean), henna, lac-dye (India and Southeast Asia), the kermes insect, or the Polish cochineal insect (Eastern Europe); browns from barks, gall, or various fruits; and purples from orchil (extracted from lichen) or the glands of certain snails. Greens were created by double dyeing weld and woad, while oranges were produced by double dyeing madder and weld.[14] Deeper shades were achieved by double dyeing. Unfortunately, some colors, such as the purples and yellows, have now faded to a dull brown.

When Coptic textiles were first produced, dyeing wool and silk was an established technique. One of the most important colors was “true” purple, which was extracted from sea snails. True purple ranged from red-purple to blue-purple, with red-purple having the most important social status since clothing with this color was associated with kingship. In the archaeological record, the darker blue-purple is most commonly found, and often in smaller quantities, on clavi or other ornaments against an undyed background. However, even the blue-purple was too expensive for many individuals and imitations were created, primarily from a combination of madder with woad. A Greek list of colors composed in 327 CE has a recipe for an inexpensive version of purple made from madder and the costly Tyrian purple, as well as orchil.[15]

By 600 CE true purple fell out of use because it was a color more suited for wool and did not work well with silk. Nonetheless, the color was so important that the madder-woad imitation served as the primary color and the combination of purple-undyed textiles remained a favorite even after the Arab conquest. By the sixth century, red became an acceptable alternative background for clothing decorations. Through Sassanian influence new color combinations were developed, including several simple bright colors brought together, while purple was replaced with variations of blue. In addition, with the increased usage of silk a new group of animal dyes were employed. Here, insects were utilized, specifically the Armenian cochineal from Turkey, which produced a pinkish red, and the Indian lac, which generated a bright red.[16]

Social Implications

In the first centuries CE, Egypt was a land of multiplicity with Greeks, Romans, and Arabs having conquered the area. With this multiplicity came various religious beliefs, as seen in Coptic textiles. Most textiles are either neutral, in that they depict vegetation or geometric patterns (this is particularly the case with early monochromatic textiles) or else have pagan imagery from the Hellenistic-Roman period, which extended well beyond the collapse of the Roman Empire. There are several instances of overt Christian images, but this is not as prevalent as pagan or neutral images. Moreover, while some textiles have pagan images, these images may be interpreted as Christian. The Spencer Museum of Art at the University of Kansas, for example, has a textile fragment of a decorative roundel possibly from a tunic or curtain that depicts an unidentified male figure in the upper register (horizontal band) in the center seated on a throne (fig. 3). He is surrounded by a nimbus (halo) and is holding a scepter. This figure may represent Jesus or a saintly figure. However, the other figures surrounding him, as well as the figures in the third register (winged putti carrying offerings), are not clearly Christian, nor are the geometric designs in the second register. Consequently, this textile could be interpreted as either Christian and/or pagan.

Figure 3. Coptic textile fragment, circa sixth to eighth century CE; linen and wool. Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, William Bridges Thayer Memorial, 1928.0018.

Like other early Christians, Coptic Christians adopted many pagan motifs as their own, in turn Christianizing them. This was commonplace in part because the Hellenistic-Roman style and motifs immediately preceded the Coptic period and overlapped with it. This is seen in the Coptic textiles, particularly in the third and fourth centuries, but even as the style changed to be more abstract, reflecting Byzantine art, for the most part classical motifs stayed the same. This was also the case for other parts of the ancient Near East, such as in Syria, where textiles with classical motifs and styles were found at Dura-Europos, Palmyra, and Halabiyeh (Zenobia).[17]

The effects of multiplicity on Coptic art in general, as well as the textiles specifically, recall the influence of multiplicity seen in mummy portraits, which were found primarily in the Fayum region. These portraits were produced between 30 CE and as late as the mid-fourth century CE (fig. 4).

Figure 4. Portrait of a Woman, Egyptian (Antinoöpolis), Roman Period (130–161 CE). Encaustic on wood panel with gilt stucco, 17 l/2x 6 3/4 inches (44.5 x 17.1 cm). The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 37-40. Photo courtesy Nelson-Atkins Media Services / Jamison Miller.

The Hellenistic and Roman Egyptians made a concerted effort to exhibit not only their social status, but also their religious and ethnic affiliation. For visitors to the home during a person’s lifetime, and for future generations who would see a portrait on that person’s mummy, it was important to include features that indicated who the deceased had been in society. This was especially true regarding ethnicity. When the Greeks first arrived in Egypt, many married locals. In the process, Greeks, and subsequently Romans, adopted Egyptian religious practices and beliefs. In turn, the Greeks brought their skills as artists and their educational system. The mummy portraits reflect these changes in the Egyptian landscape. There was a sense of multiple belonging, if not by blood, then by cultural and religious ties.

While for the Copts this multiple belonging is more organic, there is still a realization and, at least to some degree, acceptance of their cultural connections with the classical past that long remained in the region. After the Arab invasion, this idea continued. As previously mentioned, Arabic/Islamic motifs and color schemes entered Coptic art and textiles, almost melding both worlds together.

Art represented on textiles was a means for Copts to express their sense of multiple belonging. Two roundels from the Spencer Museum of Art demonstrate this sense of belonging and multiplicity well (figs. 5 and 6). They show a change in style from Hellenistic-Roman to indigenous, but the iconography is pagan, remnant of the classical period, or perhaps is pagan that has been transformed to represent Christian beliefs.

Finally, it is important to note that, from at least the period of the Persians (525–404 BCE) through the Roman Empire to the Islamic Conquest, Egypt was one of the first known multi-cultural civilizations. This was in large part because of Egypt’s proximity to Africa, Asia, and Europe. Egypt is at the confluence of these three continents and all that they bring with them.

Figure 5. Coptic textile fragment, circa sixth to eighth century CE; wool and linen. Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, William Bridges Thayer Memorial, 1928.0126.

These two ancient roundels were cut from larger textiles and may have been sewn together in the modern period to sell to tourists. The center roundel has two winged putti (nude young males) and two wingless putti. The central figure, possibly a young female, is holding a blue bird. The two figures above are holding a bowl of fruit, which is a symbol of plenty. The two-winged figures are presenting offerings, which is typical of putti. Between the putti are quadrupeds. The outer roundel shows Sassanian Persian horsemen, wearing short tunics and leggings, fighting lions. The Sassanians (also referred to as Sassanids, third to seventh century CE) were in Egypt between the sixth and seventh centuries CE, having originated in Persia.

Figure 6. Coptic textile fragment, circa sixth to eighth century CE; wool and linen. Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, William Bridges Thayer Memorial, 1928.0126 (detail of inner roundel; photo taken by Tashia Dare).

Loom: Tool used to stretch warp threads in equal tension while weaving; often includes heddle rods, lashes, and pedals.

Loop Weave (short and long): Added weft threads that protrude from the surface of the fabric; used as decoration.

Plain Weave (also known as tabby weave or cloth weave): One of the simplest weaves. One weft thread is woven under and over alternate warp threads and the next weft thread is woven over and under alternate warp threads. Each warp and weft thread is visible.

Selvage: The finished edge of a textile that is parallel to the warp and is often of a heavier weave than the body of the textile.

Sprang: Threads stretched across a frame and twisted and interlaced.

Tapestry weave: A weave that has more wefts than warps with the warp being nearly invisible; in patterns, the wefts are woven back and forth as needed.

Warp: Threads stretched across a loom between the warp and cloth beams that forms the groundwork of a fabric. Warp threads run lengthwise.

Weft: Threads run widthwise across a textile, passing over and under the warp threads.

Bibliography

Baginski, Alisa, and Amalia Tidhar. “Glossary.” In Textiles from Egypt, 4th–13th Centuries C.E., 24–33. Jerusalem: L. A. Mayer Memorial Institute for Islamic Art, 1980.

Granger-Taylor, Hero. “Coptic Textiles in the Detroit Institute of Arts.” Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts 79, no. 1/2 (2005): 46–59. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41505003.

Hunt, Lucy-Anne, Hero Granger-Taylor, and Dominic Montserrat. “Coptic Art.” Oxford Art Online. Grove Art Online. (2003). http://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000019365.

Hofmann-de Keijer, Regina. “Dyestuffs in Coptic Textiles.” In Verletzliche Beute: Spätantike und frühislamische Textilien aus Ägypten (Fragile Remnants: Egyptian Textiles of Late Antiquity and Early Islam), edited by Peter Noever, 26–36. Vienna: Hatje Cantz,

Thomas, Thelma K. “Coptic Byzantine Textiles Found in Egypt: Corpora, Collections, and Scholarly Perspectives.” In Egypt in the Byzantine World, 300–700, edited by Roger S. Bagnall, 137–62. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Van Strydonck, Mark, Antoine De Moor, and Dominique Bénazeth. “14C Dating Compared to Art Historical Dating of Roman and Coptic Textiles from Egypt.” Radiocarbon 46, no. 1

(2004): 231–44.

Völker, Angela. “Late Antique and Early Islamic Textiles.” In Verletzliche Beute: Spätantike und frühislamische Textilien aus Ägypten (Fragile Remnants: Egyptian Textiles of Late Antiquity and Early Islam), edited by Peter Noever, 8–19. Vienna: Hatje Cantz, 2005.

Further Reading

Carroll, Diane Lee. Looms and Textiles of the Copts: First Millennium Egyptian Textiles in the Carl Austin Reitz Collection of the California Academy of Science. (Memoirs of the California Academy of Sciences). Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1988.

Hoskins, Nancy Arthur. The Coptic Tapestry Albums and the Archaeologist of Antinoé, Albert Gayet. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2004.

Lewis, Suzanne. Early Coptic Textiles. Stanford Art Gallery. Stanford University. May 4 to May 25, 1969. Stanford: Stanford University Department of Art, 1969.

Maguire, Eunice Dauterman. Weavings from Roman, Byzantine and Islamic Egypt: The Rich Life and the Dance. Champaign, IL: Krannert Art Museum and Kinkead Pavilion, 1999.

Rutschowscaya, Marie-Hélène. Coptic Fabrics. Paris: Adam Biro, 1990.

Trilling, James. The Roman Heritage. Textiles from Egypt and the Eastern Mediterranean 300 to 600 AD. Washington, DC: Textile Museum, 1982.

[1]. Mark Van Strydonck, Antoine De Moor, and Dominique Bénazeth, “14C Dating Compared to Art Historical Dating of Roman and Coptic Textiles from Egypt,” Radiocarbon 46, no. 1 (2004): 231.

[2]. Hero Granger-Taylor, “Coptic Textiles in the Detroit Institute of Arts,” Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts 79, no. 1/2 (2005): 48, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41505003.

[3]. Lucy-Anne Hunt, Hero Granger-Taylor, and Dominic Montserrat, “Coptic Art,” Oxford Art Online, Grove Art Online, 2003, https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T019365.

[4]. Granger-Taylor, “Textiles,” 48.

[5]. Granger-Taylor, “Coptic Textiles,” 48.

[6]. Angela Völker, “Late Antique and Early Islamic Textiles,” in Verletzliche Beute:Spätantike und frühislamische Textilien aus Ägypten (Fragile Remnants: Egyptian Textiles of Late Antiquity and Early Islam), ed. Peter Noever (Vienna: Hatje Cantz, 2005), 17; Alisa Baginski and Amalia Tidhar, “Glossary,” in Textiles from Egypt, 4th–13th Centuries C.E. (Jerusalem: L.A. Mayer Memorial Institute for Islamic Art, 1980), 26.

[7]. Granger-Taylor, “Coptic Textiles,” 48.

[8]. Granger-Taylor, “Coptic Textiles,” 49–50.

[9]. Granger-Taylor, “Coptic Textiles,” 51.

[10]. Thelma K. Thomas, “Coptic Byzantine Textiles Found in Egypt: Corpora, Collections, and Scholarly Perspectives,” in Egypt in the Byzantine World, 300–700, ed. Roger S. Bagnall (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 150–51.

[11]. Granger-Taylor, “Coptic Textiles,” 53.

[12]. Granger-Taylor, “Coptic Textiles,” 53.

[13]. Regina Hofmann-de Keijer, “Dyestuffs in Coptic Textiles,” in Verletzliche Beute: Spätantike und frühislamische Textilien aus Ägypten (Fragile Remnants: Egyptian Textiles of Late Antiquity and Early Islam), ed. Peter Noever (Vienna: Hatje Cantz, 2005), 27.

[14]. Hofmann-de Keijer, “Dyestuffs in Coptic Textiles,” 31.

[15]. Hofmann-de Keijer, “Dyestuffs in Coptic Textiles,” 27.

[16]. Information in this paragraph is indebted to Granger-Taylor, “Coptic Textiles,” 55–56.

[17]. Thomas, “Coptic Byzantine Textiles,” 154.