Tashia Dare

Introduction

Museums have been described in numerous ways over the decades and serve a variety of functions within local, regional, national, and international communities. They are sites of public trust, educating through exhibitions and programs. Museums are a public space of study and are meant to enlighten visitors about the past, the present, and the future. Museum exhibitions today frequently ask visitors to consider how the past is relevant to today and to the future, contemplating where we are heading. They help inform and shape our personal and collective cultural and social identities. Since museums are actively part of our communities it is necessary to understand the history of these institutions. Questions of how, when, and why museums came into existence need to be investigated. This section focuses on the origins of museums from the ancient Near East through the European Renaissance to the Enlightenment period and the Age of Museums.

Etymology

The concept of “museum” or musaeum in Latin is a complex one (see box 1). It encompasses both the private and the public as understood in various time periods; it includes contemplative study, humanistic collecting, and social dynamics of power, prestige, and display.[1] The term brings together intellectual, philosophical, and spatial underpinnings. Museums as they are known today were initially shaped by social, economic, political, and religious dynamics of the 16th and 17th centuries in Europe. They further evolved through the subsequent centuries reaching their zenith in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Today, they continue to modify and challenge conventional methods of exhibiting collections and how and what we learn.

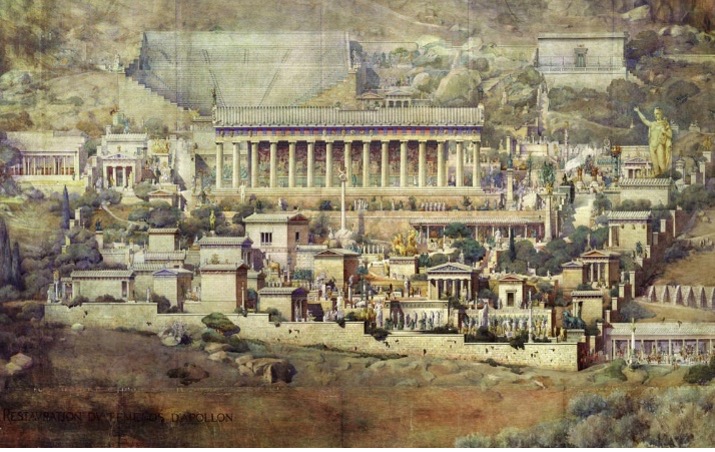

The word “museum” originates from the Greek mouseion, which is “the shrine or home of the muses.”[2] The muses are nine sister-goddesses who are associated with literature, the arts, and sciences. They are thought to be the sources or personifications of knowledge for poets, historians, astronomers, philosophers, musicians, and others.[3] The term was used by Athenian writers metaphorically, but it was also used to refer to a school where letters and the arts were taught. [4] The word was likewise used for the Temple of the Muses or the Museum of Alexandria, which was likely founded by Ptolemy I Soter in the late 3rd century BCE in Alexandria, Egypt and existed until possibly as late as 529 CE when Emperor Justinian closed all pagan schools.[5] The Temple of the Muses (fig. 1) may have held collections of art and natural history, a zoo, and a botanical garden.[6] It may have been connected with the well-known Library of Alexandria. The Museum of Alexandria was open to scholars and students and may have functioned more like a university and research institution than a museum as we know them today.[7] The mouseion was a vital center for Hellenistic intellectual life and several prominent thinkers were associated with it including Euclid, Hero, Claudius Ptolemy, Eratosthenes of Cyrene, and Herophilos of Chalcedon.[8] Ptolemy I Soter’s founding of the mouseion and the library of Alexandria and those who supported the institutions after him not only ensured the survival of many ancient texts, but also connected learning and related materials with the aims of the state that furthered the ruler’s prestige and power. This was common practice centuries later.[9]

The idea of the museum as a place of systematic collecting and studying may have originated with Aristotle during his travels to Lesbos in the mid-340s BCE. While there, Aristotle, along with his student Theophrastus, started collecting, studying, and classifying botanical specimens. As they did so, Aristotle developed an empirical methodology, which led to the need for “social and physical structures to bring into contiguity learned inquiry and the evidence necessary to pursue it.”[10] Aristotle established the Lyceum, a community of scholars and students who methodically studied biology and history among others. The Lyceum included a mouseion and it may have been during this time that the term was associated with scholarly pursuits.[11] The mouseion became a word that would be used centuries later by humanists during the Renaissance with its connection to the glorified ancient Greek past.[12]

The first time the word museum (the Latin variation of mouseion) appears is in the 15th century in reference to the Florentine Medici family’s collection as a means of prestige. The Medici family is credited with creating the first museum. However, during the Renaissance museum was rarely used. In 16th century Italy two new words were introduced to describe the idea of the museum: galleria and gabinetto.[13] Galleria referred to a long large room with lighting on the sides where paintings and sculptures were exhibited while gabinetto means “cabinet” (which will be discussed further below). The word, musée, originally appeared in French dictionaries as late as the 16th century. In 1615, museum is published for the first time in English in George Sandys’ travel book in his description of the ancient ruins of the Temple of the Muses in Alexandria. From that time forward, the word museum referred to an institution housing collections and exhibitions.[14] In Edward Phillips’ 1706 6th ed. of New World of Words: On Universal English Dictionary museum was defined as a “Study or Library; also a College, of Publick Place for the Resort of Learned Men.”[15]

Initially, the museum as it is known today was intended for collectors, scholars, connoisseurs, the educated elite and wealthy. This led to museums appearing imposing, exclusionary, “templelike,” formidable to the average person. Starting in the 19th century this gradually changed due to the increase in a democratic culture and other social factors. Public museums generally are founded with the purpose of revealing to the average person what once was concealed and hidden away.

Ancient to Medieval collecting practices

Collecting or amassing objects has been a human activity for thousands of years. People across the world and time have brought objects together for various reasons, giving these objects meaning and value. The meaning alters based on the context. Grave goods are a good example of this. Sometimes these objects were highly valued by the individual during his or her lifetime. They may also serve as an identity for the individual or as a means of serving the individual’s well-being in the afterlife (as in ancient Egyptian shabtis).

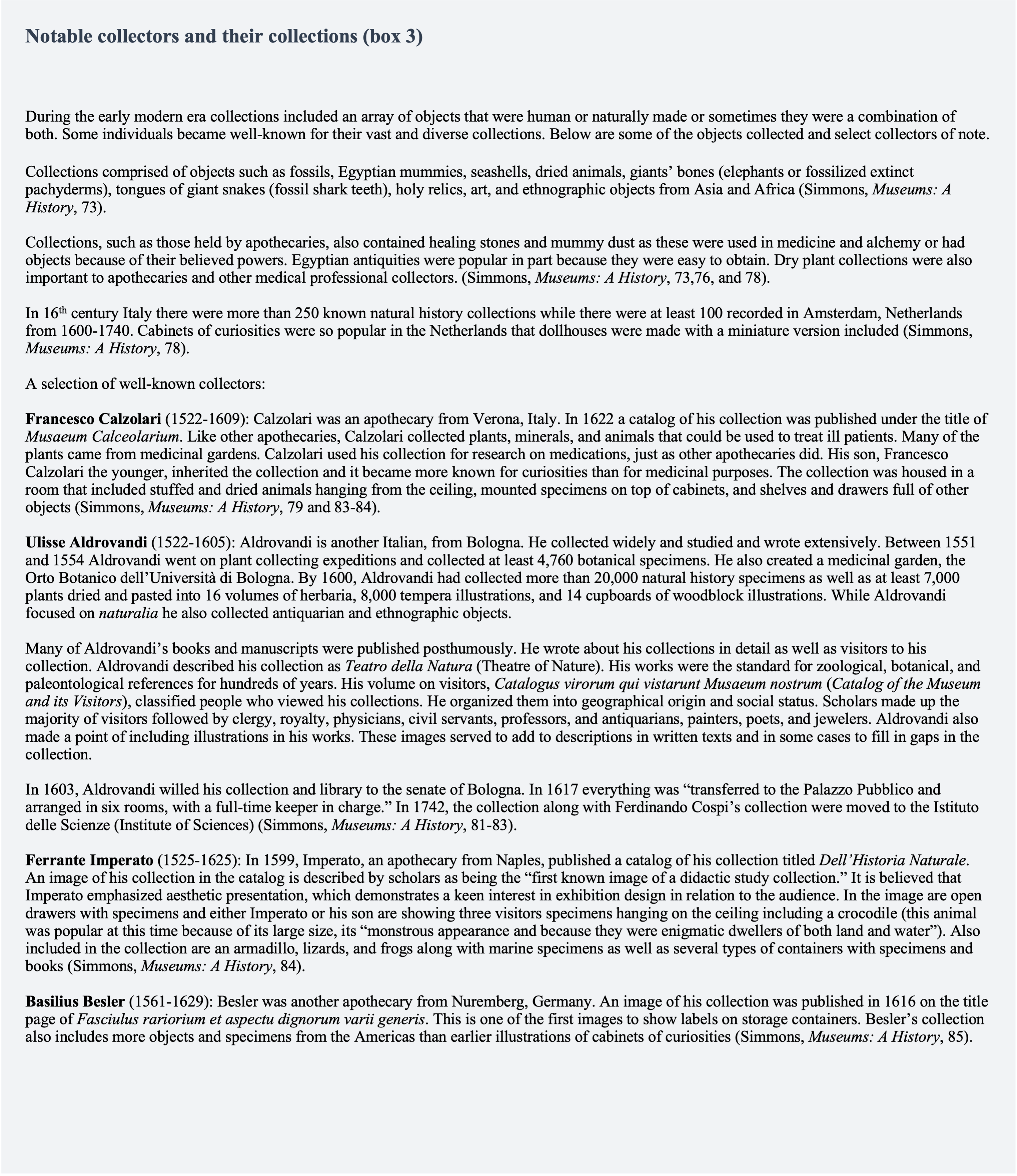

Various accounts in ancient texts and physical evidence depict kings, members of royalty, and other individuals collecting plants, shells, and various types of objects to admire and to study. An example is the Egyptian pharaoh Thutmose III (1479-1426 BCE) (fig. 2) who had an extensive collection of plants and animals from the Near East, including Lebanon and Syria, and possibly collected art and antiquities. He built a chamber or hall at Karnak Temple for a pictorial catalog of his botanical collection to be chiseled. This space is referred to by scholars as the “botanical garden.” Thutmose III built his collection from his various military campaigns, taking some objects as war booty.[16] It was not uncommon for  objects from another culture to be taken by military leaders as booty. An additional example is in Pergamon with Attalus I Soter (269-197 BCE), first king of the Attalid dynasty. Attalus collected statuary and paintings from lands he had conquered or controlled. Some of these were displayed in outdoor spaces while others may have been placed in gallery-like spaces “for local artisans to imitate.”[17]

objects from another culture to be taken by military leaders as booty. An additional example is in Pergamon with Attalus I Soter (269-197 BCE), first king of the Attalid dynasty. Attalus collected statuary and paintings from lands he had conquered or controlled. Some of these were displayed in outdoor spaces while others may have been placed in gallery-like spaces “for local artisans to imitate.”[17]

In ancient Greece, treasuries at public sanctuaries or temples played a valuable role (fig. 3). They were a place where objects donated by individuals were kept for the gods. Moreover, they were a place where spoils of war were on view, military victories commemorated, the city’s wealth and prosperity exhibited, citizens’ piety displayed, and an expression of civic pride. Donated objects included votive offerings and other religious pieces; paintings and sculptures; works made of gold, silver, or bronze; antique weapons ascribed to mythical heroes; and objects considered “unusual” (either artificial or natural).[18] Objects donated to early Greek temples created a sense of the past with the people, which connected with the social bonds of families and related obligations and the social effort that came with making the objects.[19] Many Greeks collected objects for their own homes as well, such as fossils, works of art, precious stones, and ceramics.[20]

During the classical era (early 5th century-323 BCE), in many Greek temples paintings were arranged by schools in the temple picture gallery (pinakothekai) in addition to other objects that were on public display. These objects were continually inventoried by temple guardians (the hieropoei) whose job it was to care for the treasures and offerings. Objects were stored in the entrance vestibules (prodomos) or on shelves in the inner chamber (naos).

As time shifted from Greek to Roman dominance, the use of objects also morphed. In Rome, public art was prevalent, and many people collected objects from various parts of the Empire. For example, the display of Greek statuary in public spaces in Rome, including temples and public buildings, demonstrated the empire’s power and expanse to both the res publica (commonwealth) and to foreign emissaries and traders in the city.[21] Additionally, the Forums of Augustus and Trajan were, in a way, national portrait galleries. Administrative offices already in existence were expanded to include caring for public statuary, usually through the aediles, censors, and later curatores. Sometime between 11 BCE and 14 CE, Emperor Augustus instituted a curatorial board, which “was responsible for the collections and the buildings which housed them.”[22] By circa 200 CE, the positions of adiutor rationis statuarum, person in charge of three-dimensional statues, and the procurator a pinacothecis, curatorial official in charge of pictures, existed. Records show that in 335-7 CE there was a curator of statues.[23] Rome also had several art historians, art advisors, and art markets. In 1st century Rome there was a sizeable market for ancient Egyptian artifacts. Finally, while emperors and other politicians collected works of art or even fossils, families, private individuals, town councils, and temples held their own collections including assemblages of silver and gold plates as well as complete sets of domestic plates, drinking silver, women’s toilet sets, and domestic cult objects.[24]

In medieval Europe (mid. 5th century-mid. 15th century) the church was the primary center of learning and preserving knowledge. Monasteries and churches mainly collected and preserved relics, illuminated manuscripts, religious art, silver, textiles, and other items related to liturgy. They also sometimes collected historical objects, ceramics, classical statuary, natural specimens, and rare and unusual objects. During this period, objects played an integral role in the lives of individuals, particularly those closely linked with saints. Relics of saints, both of a corporeal nature, as well as closely associated objects, were believed to have power. They were where the earthly and divine worlds met.[25] Relics were linked with miracles, which made them even more precious and worthy of being collected by churches and individuals and of pilgrims visiting them.

In the medieval period, the material world could be seen in view of God, connecting humans with the divine. The material world directly showed the divine will of God. The study of and the delight in the material world were spiritual exercises in contemplating rarities that were viewed as miracles, aesthetic expressions, and understanding of material organization that came together “for the greater glory of God.”[26] These ideas persisted, to some degree, throughout the Renaissance, or the early modern era, as well.

While much of Europe struggled throughout the period because of declining economies and education, as well as numerous conflicts, there was an expansion in trade and exploration, which enlarged what people collected. Some of the objects collected were brought back to Europe by Crusaders from the Holy Land. They were often given to church and monastic treasuries and, in some cases, kept in private collections. Many objects were listed in church treasury inventories since they were viewed as having generated heavenly rewards for the donor and earthly commemoration.[27] In addition, objects in church treasuries could serve as cash reserves when needed.[28]

Cabinets of Curiosities- The Renaissance or the early modern era

The Renaissance (mid-14th century-1600) (from here on referred to as the early modern era) played a fundamental role in the history of museums. This period was about knowledge and understanding the world in new ways. Collections and the act of collecting represented this. The period was a transition from the medieval era, which was largely centered around the church and was the source of knowledge and learning, to the Age of Enlightenment, where rationality and individuality took precedence. The early modern era saw the beginning of the church more closely align with nation-states and novel philosophical ideas.

Analyzing collections of the early modern era gives us clear insight into the views and thoughts of individuals and families of the period as well as parts of society as a whole. Collections during this time represented the power, prestige, social standing, and intellectual interests and prowess of the collector. They crafted new social practices such as a trade in exotic objects as well as new social relationships, including those between collectors and their patrons. Furthermore, the quality of a collection was a way of expressing identity and social distinctions (the idea that personal identities could be fashioned instead of being solely assigned at birth was relatively recent).[29] Collections could be seen as the universe in microcosm as collectors attempted to obtain a variety of objects and to express their ability to have power over the macrocosm as a result. These collections, as well as libraries, conveyed religious and political ideas with religion and philosophy actively playing a role in the shaping and function of 17th century museums.[30]

Three of the greatest hallmarks of the early modern era are advances in technology, travel, and trade. Advancements in shipbuilding and navigational tools allowed longer-distance travel around the globe, which opened more cultural and economic trade and commodification. With greater diversification in banking and domestic market economies, a new middle class grew. More Europeans had disposable income that they could use to purchase rare and unusual items, and they had more leisure time to enjoy them. Consequently, there was a rapid intensification of private collections, especially among the wealthy. Innovations in glassmaking, better paper quality and quantity, printing with moveable type, increased literacy rates, and improvements of indoor lighting further helped with changes in collecting practices and displaying objects. Collecting was spurred by the dissemination of ancient texts, new discoveries, and exchanges as well as more systematic ways of communication. Because of societal changes, collecting was a way for people to make sense of the material available, of their expanding world, and of “divinely inspired nature.”[31] It was about celebrating the objects themselves and a means of seeing divine skill.

Another hallmark of early modernism is the intellectual framework of natural theology. As with earlier generations intellectualists thought of themselves “as approaching the mind of God.”[32] At the basis of this are two fundamental ideas. The first is the belief in human reason and one’s ability to observe, infer, and understand the workings of the universe and to share this information with others, thus building basic fundamental facts. The second is that the material world is supreme and one can make deductions about the world based on this and the relationship between parts of the material world. It was believed that humans were capable of objective knowledge, and the primary way of achieving this was through material evidence. “Collections, therefore, do not merely demonstrate knowledge; they are knowledge.”[33]

Previously, medieval collections in church treasuries and in private homes represented power and wealth. This was still the case in the early modern era, but they also expanded to be “microcosms of the macrocosm, distillations of the universe” and about the production of knowledge.[34] The rise in collections that led to the eventual creation of the museum parallels with the decline in the church being the center of knowledge and having institutional power “to provide adequate narratives, and their physical depositories.”[35] Furthermore, scientific inquiry intensified during the early modern era, particularly in the second half of the 16th century. As a result, there was an increased enthusiasm in bringing together objects and scientific exploration of the natural world.[36] Since acquiring objects could be expensive, collectors/scholars turned to royalty and the church for patronage. Not only did this type of patronage allow for the creation and maintenance of collections, but it also brought collectors/scholars into European courts “to inspire and entertain.”[37]

modern era, but they also expanded to be “microcosms of the macrocosm, distillations of the universe” and about the production of knowledge.[34] The rise in collections that led to the eventual creation of the museum parallels with the decline in the church being the center of knowledge and having institutional power “to provide adequate narratives, and their physical depositories.”[35] Furthermore, scientific inquiry intensified during the early modern era, particularly in the second half of the 16th century. As a result, there was an increased enthusiasm in bringing together objects and scientific exploration of the natural world.[36] Since acquiring objects could be expensive, collectors/scholars turned to royalty and the church for patronage. Not only did this type of patronage allow for the creation and maintenance of collections, but it also brought collectors/scholars into European courts “to inspire and entertain.”[37]

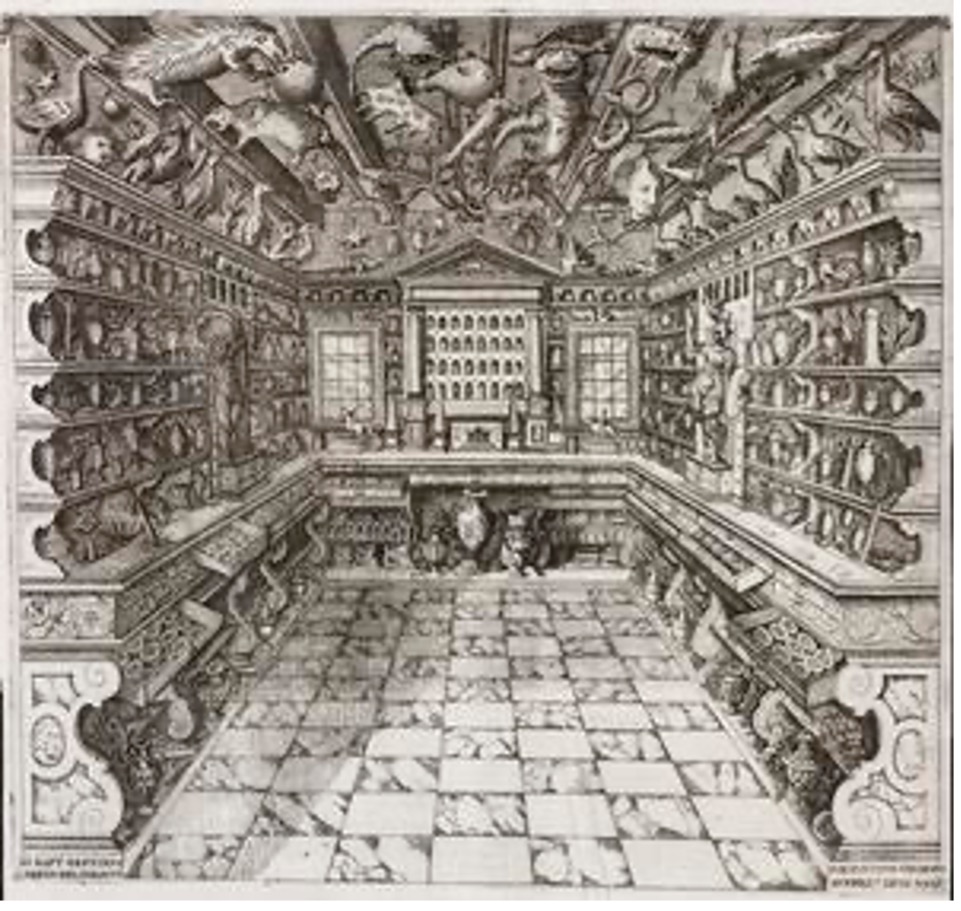

Collections held objects that were viewed as exotic, unusual, rare, extraordinary, or valuable objects and sought to interpret the world and reflect the collector’s learnedness and sophistication.[38] It was at this time that the first “cabinets of curiosities” or “cabinets of the world” came into existence in Europe, which aimed at revealing the order of the world. Many terms were used to describe collections (box 2). Cabinets of curiosities ranged from collections displayed in actual cabinets to rooms to whole wings in palaces (fig. 4).

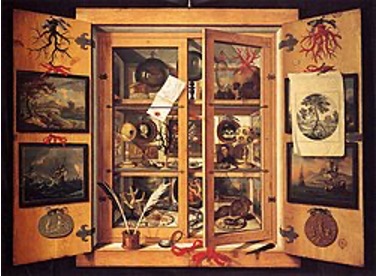

During this time “cabinet” referred to a container, usually a cupboard with shelves and drawers that held a collection of small objects (fig. 5).[39] In Italian gabinetto, or cabinet, was a square-shaped room with small works of art like medallions, statuettes, and curios as well as stuffed animals and botanical rarities.[40] In Britain from the early 17th century onward “cabinet” described a closet past the main bedchamber where the owner displayed his collection of curiosities, pictures, and other small works of art for viewing by close friends and other distinguished guests.[41] In France, “cabinet” referred to a small room as opposed to the “salon” which was used for grand occasions.[42] Early modern collections were owned by royalty, rulers, government officials, and middle class individuals and families including apothecaries, physicians, clerics, scholars, and lawyers. The kind of cabinet depended on the owner of the collection, the type of power of the owner (financial, intellectual, magical, political), and the world view the owner ascribed to. The network of collectors spread greatly, bringing together families, dynasties, and alliances as well as scholarly connections, patronages, gifts, and mercantile exchanges.[43] Objects were traded among collectors, with the quality of the object demonstrating the collector’s value or worth.

Displaying one’s collection within one’s own home was a means of demonstrating and gaining social prestige and standing as collectors were associated with each other through contacts and the circulation of handbooks, manuscripts, and other texts.[44] Many collectors had their collections in their studio or study, which was usually in the innermost room of the house next to the owner’s bedroom. When the studio, or an adjacent space transformed into one, was open to certain people it became a mouseion in the classical sense as it turned into a place where scholarly conversation took place in relation to the collections. As a result of the importance of these conversations to the development of early modern civil society, collections were more and more seen as semi-public forums.[45]

An example of the preceding is the Medici family’s collection. In the 1570s Francesco I de Medici (1541-1587) (fig. 6) designed a secret space in his Florentine palace, known as the studiolo, which was a small room with no windows that resembled a large cupboard. This room held objects within

cupboards that were then painted with images related to the contents. There were paintings on the walls too. The objects were organized according to a hierarchy “of the world as a microcosm of art and nature, in which the prince could appear symbolically as ruler.”[46] The relationship of art and nature to the elements, the humors, and the seasons as seen in mythology, literature, history, and contemporary technology was articulated through the studiolo.[47] The studiolo demonstrated a particular power-knowledge

relationship in which the prince knew the world he reigned over, but also “knowing” in its own right. The closed cupboards mediated the prince’s access to the visible (the contents painted on the exterior of the cupboards) and the invisible (the contents inside the cupboards) and therefore to the order of the cosmos which the cupboard’s contents represented.[48]

Collections of highly valuable objects formed the basis of power and the transmission of that power among the ruling strata of society rather than to the general populace. Consequently, most princely collections were held privately with few people having access to them, namely monarchs, dignitaries, and ambassadors who sometimes brought gifts that were added to collection.[49] Princely painting and drawing collections were a tangible means of demonstrating the prince’s power and wisdom.[50] In turn, visitors supported the prince’s power by viewing the collection. This was the same for Francesco I de Medici until 1584 when he moved his collection to the Uffizi Gallery, in Florence, making it open to the public. The unusual act was intended to show public legitimization of the family’s dynasty.[51] The Medici collection demonstrates what was taking place politically, religiously, and intellectually at the time.[52] The political situation required a shift in relationships of spaces, objects, people, visibility, and accessibility.[53] Previously, Lorenzo de Medici (1448-1492) and his court described the collection using the term “museum” as it connected them with the classical past, adding to the prestige of the Medicis and their collection.[54] In 1743, the Medici collection was bequeathed to the state of Tuscany.[55]

Early on collections were organized in a way that transmitted knowledge. As cabinets of curiosities expanded, new and elaborate systems of classification were necessary. However, a uniform way of classification had not been established at this time. Each collector had his own method, and the collecting and arranging of objects positioned the collector within the system of order. The organization and classification of collections reflected the collector’s own worldview and at times were based on an imperfect understanding of nature. Published books at the time listed objects as falling under supernatural “(miracula, sublimely mysterious miracles and transcendent divine interventions), natural objects (naturalia, the odd wonders of nature-mythic, monstrous, and real), and artificial objects (artificialia, such as technological advances).”[56] Collectors desired that their collections represent the “microcosm,” which in turn helped understand the divine. Observation of the natural world took on fervor. The world was divided into the macrocosm, that of God whose results were understood as Nature, and the microcosm, that of human beings whose results were understood as art.[57] There was a desire to bring nature and art together, the artificial with the natural, as well as an appeal to see a continuity between nature and art. Collections confirmed the “existence of a divine order in the world.”[58] The interrelationship between objects placed in either category relates to the interrelationship between God and humans, of the macrocosm and the microcosm, of the unity of creation (box 3).[59]

By 1565 collections and classification systems had advanced enough that Samuel von Quiccheberg, librarian for the Duke of Bavaria, wrote a book about collection organization titled, Inscriptiones; vel, tituli theatric amplissimi (Inscriptions; or, Titles of the Most Ample Theater). This book is considered to be the first museological treatise focused on the systematic organization of collections, large and small, that was used from the mid-16th to early 18th centuries.[60] Quiccheberg believed that cabinets of curiosities should promote collecting in an encyclopedic manner and be a place of research and display, be considered a form of scholarship that promoted knowledge, and be a site of education in the arts, crafts, and sciences.[61] He thought that collecting gave collectors a way to access knowledge outside of texts alone.[62] Furthermore, Quiccheberg believed that bringing together objects and categorizing them added value to them and promoted new knowledge of the world. He identified five primary classes of collections that linked with the universe as a whole with ten or eleven further subdivisions or specifications: paintings and sacred objects; artificialia (such as sculptures, numismatic, and applied arts); naturalia representing the realms of earth, air, and water; artifacts (such as those related to science and mechanics, games, sports and pastimes, arms and armor, and costumes); and objects “glorifying the founder” of the collection (such as heraldry, portraits, genealogy, engravings and paintings, textiles, and furnishings).[63] Quiccheberg thought there should be a library, printing shop, and various workshops connected with the display of objects as well.

The practice of classifying objects and collections helped move people from merely collecting to the idea of a museum as we know it today. Cataloging was an indispensable feature of this. This aspect of collecting started in the late 16th century. Catalogs allowed for interpretation and analysis of collections.[64] They were sometimes published, giving further status to collectors. The catalogs were scholarly and practical, demonstrating the value of collections. They allowed people to study collections and the relationship between objects even when not in the presence of the collections.[65] Over time, many catalogs became elaborate publications with text and illustrations of objects, just as we do today.

The Institutionalization of Museums

While scholars agree that the first building intended to function as a museum was constructed by the end of the Renaissance, there is debate about which specific building should be considered the first purpose-built museum. Some historians think that the oldest purpose-built museum is the Mint (Münzhof) in Munich, Germany. This was designed by Wilhelm Egkl and built from 1563-1567. It housed the collections of paintings and antiquities of Wilhelm IV (1493-1550) and Albrecht V of Bavaria (1528-1579), which were created during the 1560s and 1570s, as well as the Bavarian mint from 1809-1983. Various parts of the building held different aspects of the collections. This includes the Antiquarium, established in 1568, which displayed antiques and sculptures on the ground floor, while a library was on the top floor. Early on, the collections were only open to princes, ambassadors, artists, and scholars.[66] Another suggested structure is one commissioned by Archduke Ferdinand II (1529-1595) for his collection at Schloss Ambras, in Innsbruck, Austria, in 1573, where he expanded the Lower Castle (fig. 7). This structure was for the first time specifically intended to house collections. Schloss Ambras was made up of four interconnected buildings. Three were for arms and armor, including the Turkenkammer (holding trophies from the Turkish wars) and the Helden Rüstkammer (the Heroes Armory). The fourth was the innermost, the Kunstkammer, which had twenty display cases and all the rooms were connected to each other. This building also had an Antiquarium.[67]

At the end of the Renaissance, a shift took place. The philosophical underpinnings of the cabinets of curiosities, the interest in the marvels, made way for advanced scientific viewpoints. As a result, many collections were either consolidated or expanded and started to open more to the public, leading to the first modern museums. As this occurred collections began to become fragmented and specialized in disciplines such as art, history, and the natural sciences.[68] In addition, most purpose-built museums by this time had a library attached to it. The library, just as much as the museum itself, organized the expansion of knowledge and classification during the 16th and 17th centuries.[69]

Museums in the Enlightenment Period

The Age of Enlightenment or Reason (18th century) and the birth of the scientific revolution (16th-17th centuries) coincide with one another.[70] Travel, discovery, and imperialism intensified during this time. Learning changed as empiricism, experimentation, and inductive methods of reasoning became the primary mode of knowledge formation in addition to the “institutionalization of science through the formation of the first scientific organizations.”[71] Collections became vital to growing scientific inquiry and reasoning. During this time collecting, classifying, studying, arranging, and displaying objects became ever more critical to examining the relationship of humans and the world around them.[72]

Collections became more extensive with the surge in scientific discoveries and methods. “The encyclopaedic vision of knowledge, born of the humanist desire to recapture the knowledge of the ancient world, was used for a variety of purposes by the seventeenth century,” including for pedagogy, expanding knowledge, social and political messages, and for proselytizing.[73] During the 18th century people focused on finding the basic natural laws that governed the universe and human beings. Scholars of the time wanted to preserve this information through museums by collecting natural specimens, artistic works, and scientific creations.[74] The idea was that these collections would help educate people and aid in humankind’s “steady progress toward perfection.”[75] Museums maintained the encyclopedic or universal idea “of the world-in-microcosm” inherited from the previous generation.[76]

While collections became more encyclopedic they also became more specialized, most of which could fall under three broad categories of museums: art, history, and nature.[77] The categories are based on the type and use of the objects within collections, with art gaining much greater prestige than the other types of collections. In 1727 Caspar F. Neickel (Neikelius) published in Latin Museographia where he defines museum as a “chamber of treasures-rarities-objects of nature or art and of reason,” with art referring to human-made objects including works of art and books.[78] He writes that knowledge of the physical world can only be acquired through collections and libraries. Neickel notes that museums help people to understand themselves and the world around them, “both divine creations, and so should contain naturalia and artificialia, and books.”[79] Neickel broke down naturalia into three groupings: regno animali, regno vegetabili, and regno minerali. Artificilia (art) was divided into fine art, which Neickel stated should be original and produced by famous masters, and applied art of all types. While the classification of nature and art was possible, historical objects such as weapons, personal items, household items, and so forth were much harder to classify, as they still are today. As a result, art as well as natural history became “morally respectable and intellectually acclaimed,” thus leading to the founding of several museums focused on these subjects and being open to the general public.[80] On the other hand, historical and exotic objects were commercialized and became part of popular culture.[81]

By 1700 science collections moved away from focusing on the rare and the odd to demonstrating similarities of types of plants and animals. Classification systems continued to evolve, becoming more and more complex and were based on differentiating groups of objects rather than unifying them.[82] Classificatory methods were a source of power and knowledge.[83] These systems were fostered by scientists Carl Linnaeus, Georges-Louis Leclerc Buffon, Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, and Chevalier de Lamarck. Linnaeus’ methods of classification were primarily used by several collectors and scientists as a means of arranging their collections in a way that is somewhat similar to how museums function today (fig. 8).

Classification systems, or having a patterned system of nature, fit in with the deist ideas of the era, matching the beliefs “that the physical process of material observation and measurement by a rational man could result in objective knowledge and truth.”[84] The methodical way of observing and comparing objects was a key element in natural science. Individual collections as well as museums increasingly viewed themselves as the primary way of bringing together and mapping the world and seeing patterns. While there were still a variety of ways of organizing collections based on understandings of the world, people’s worldviews, and interests of collectors by the end of the Enlightenment period classifying objects was in the process of being standardized.[85]

Throughout the 18th century, natural history collectors turned their attention to the commonplace objects rather than the exotic or unusual. This was in part because of a new scientific rationale that aimed to discover the laws of nature seen through recurrences in objects of the commonplace or average rather than singular phenomena.[86] There was a concern of how to communicate this information so it could be used “in the productive exploitation of nature.”[87] Consequently, classification and exhibition arrangements changed. Exhibitions became more pedagogic with the goal of making the arrangement of collections easily understood to the average person.

In addition to natural history museums changing, art museums were no longer organizing their exhibitions merely based on aesthetics but as a pedagogical tool. Linnaeus and Buffon’s system of hierarchical scientific nomenclature inspired a new classification system of art. As a result, exhibitions and gallery spaces were grouped by schools and artists. Within each school art was placed chronologically, creating art historical periods (something that can still be observed in art museums today) and a journey through history for visitors. Works of art were placed within uniform frames and clearly labelled.[88] However, unlike natural history collections which sought commonality among objects, the singularity of individual works of art was still essential.[89] Visitors now not only saw beautiful works of art, but also learned about the history of art.[90] Doing so allowed visitors to learn rather than just merely appreciate something. It produced historical depth for those just understanding that their present was a result of the past.[91] During the 18th century, royal collections that were made public continued to validate the sovereign’s power by making the collection available to the public. Furthermore, the development of putting royal art collections into national schools and art historical time periods codified visibility of a nation’s history and art history in a new way.[92]

As more museums were built, they were also seen as a tool that could be used to promote nationalism and bring together ideas and concepts in more accessible ways for the public. Many royal collections started to open to the public while numerous private collections were turned over to the state and transformed into public museums. A notable example of the latter is Elias Ashmole’s collection that was eventually donated to his alma mater, Oxford University, thus founding one the first university museums in 1683 (the Ashmolean Museum). Through national museums individuals could connect with the state and be educated by the state.[93] By the end of the 19th century, most western European countries had a national museum.[94]

It was during the Enlightenment Period that two prominent national museums were inaugurated, the British Museum and the Louvre. The British Museum (fig. 9) was founded by an act of Parliament in 1753 after Sir Hans Sloane’s (1660-1753) immense encyclopedic collection was purchased by the British government. Sloane was a physician who spent time in Jamaica as the island’s governor’s personal doctor. His collecting began in Jamaica gathering naturalia, which he then supplemented with various purchases including three other naturalists’ entire collections. Sloane’s collection and two libraries (the Harleian Library and Sir Robert Cotton’s library) initially formed the British Museum “as a public repository of objects and texts” that were to be permanently maintained by the English government.[95] A third library (the Royal Library) was added in 1757. The libraries were a key addition as they served as a research tool while the museum continued to collect widely. The museum slowly opened to the public as a national, imperial, and encyclopedic museum and actively supported scholars.[96] This initial slowness to open to all members of the public was from a desire to regulate which members of society could enter.

The Louvre, opened in 1793, is thought to be the first national museum of art (fig. 10). It was founded in the wake of the French Revolution when the Cabinet due Roi and the Cabinet d’Histoire Naturelle became the property of the French people rather than the king. The name, muséum, was chosen for these collections and other public collections because it evoked the glories of the past, of ancient Alexandria, “and implied intellectual achievement and monumental architecture.”[97] Through a decree in 1789 French revolutionaries took church property and property from the king, émigrés, and the royal academies, including paintings and other works of art, transferring ownership to the people and creating a national patrimony from this. The Grand Gallery in the Louvre Palace was renamed the Muséum Français (in 1796 the name was Musée Central des Arts and in 1803 Musée Napoléon).[98] During his reign, as Napoleon took over territory in Europe he confiscated countless works of art as war indemnities with the aim of designing a unified French museum system that exhibited France’s imperial goals. The Louvre served as the central museum. With more time, 15 public museums were conceived to house artwork no longer beneficial to the Louvre.[99] While Napoleon’s plan did not come to fruition because he was dethroned, the idea of the museum being an instrument of national glory expanded throughout Europe.[100] In addition, many central museums in territories occupied by Napoleon were modeled after the Louvre, such as The Galleria dell’Accadmia in Venice (1807), the Pinocoteca di Brera in Milan (1809), and the Prado in Madrid (1809).[101] Moreover, French imperial expansionism caused many European countries to construct their own national museums as a means to counter this expansion and promotion of the French nation, instead elevating their own culture and region or nation.[102]

The Age of Museums

During the 19th to mid-20th centuries museums flourished. They became even more specialized and diversified. The French Revolution led to a shift in museum practices in which collections were no longer just personal and private but increasingly more open to the public. Through the Revolution a democratic culture emerged. The museum was a tool used to expose the decadence and tyranny of the previous mode of governance, the ancient régime, and to strengthen the recently founded Republic. In France the newly inaugurated public museums were used by the state to educate and lead the general population, unaware, to activities that made them useful to the state. The museum not only presented knowledge and provided it to the general public, but also sought to control the public’s behavior through architecture, the creation of divided space, and methods of displaying objects.

There are many reasons why museums grew exponentially in Europe, including the rise in egalitarianism and democratic culture, an emerging market that allowed more disposable income for the middle class, an increase in literacy rates, as well as more people moving to cities. In addition, reliable and more accessible indoor gas lighting, public transportation improvements, decreased prices for plate glass, and modern aesthetic theories concerning art and architecture similarly contributed to the spread of museums.[103]

In the 19th century the idea of collecting “old things” remained a respectable practice by upper- and middle-class individuals and gained strength during this time. With the increase in middle-class income more people had opportunities to collect objects. The thought that the museum was a place to safely keep objects of the past and that older objects were worthy of collecting became more prominent because of new ideas of historicism where the past was seen as a “foreign country” that we cannot visit and “by the organizing principle of the temporal series.” The desire to collect and to look to the past was from a desire to save that past in the face of rapid, transient time. Time was understood as irreversible and change was persistent, thus the past became more recent and things quickly became “old.”[104]

Museums were both temples of the elites and utilitarian institutions for democratic education. The newly created museum instrument spread across Europe, altering ways of collecting and displaying objects.[105] New curatorial practices emerged. Additional ways of classifying objects were established and objects gained alternative meaning in the wake of the French Revolution, in large part reflecting ideas of the Revolutionaries and rewriting history in light of liberation. Ideas about storage and reserve collections surfaced and space was divided into repositories and exhibition areas. The concept of temporary exhibitions likewise began. Objects were organized according to viewing observable differences between objects, which led to seeking representative objects rather than the exotic and to seeing objects as parts of a series instead of being unique.[106] Since museums were now used to shape the general public as a beneficial tool for the state, explanatory texts were added to exhibitions and inexpensive catalogues and guides were provided to further educate visitors who were “made” into citizens of the state, through exposure to “symbols of civilization.”[107]

Methods of exhibiting museum collections also reformed. Some exhibits were based on culture history, arranged by period rooms or halls of different stages of national history. In addition, museums attempted to display as much of their collection as possible with orderly packed cases and well-organized walls full paintings and drawings. This gave the public as much access to objects from around the world as possible.[108] Museums expanded their collections through the practice of having a complete series of something such as artwork from a particular time period, and through the idea of evolution. Some museums filled in gaps in series of sculptures and skeletons with plaster casts or other replicas, though some museums preferred to have the real object.[109]

Taxonomy (classification) became an increasingly important principle concerning natural science collections. It was associated with a modern understanding of stratification and evolution. The Linnaean system was perfected and universally adopted in the 19th century (fig. 11). This created a “chronological series of flat planes of knowledge” that allowed for the description of nature based on the realization of a span of points in the geological past. This was at the same time in which the fossil record was beginning to be understood.[110] Stratigraphy (usually attributed to R. Murchison and Adam Sedgwick) developed during this time, which helped construct a chronology of time. In addition, Charles Darwin’s ideas about evolution provided a chronological structure and a hierarchy that could explain the diversity of life on earth. It was thought that geology, biology, anthropology, and history were connected to each other to develop a universal time.[111] All of this in turn helped people understand human history, including creating a national character and moral virtue as well as demonstrating human progress from “primitive” to “civilized.”[112]

Early on museums had requirements for discourse (freedom of speech and the rule of reason, for example) as well as decorum (no brawling, no eating or drinking, no spitting, no touching exhibits, no loud talking, etc.) and what to wear or not to wear. This was a way of controlling visitors and reforming certain undesired behaviors by the general populace. Initially, this was intended to distinguish between the bourgeoise and the working class, who were originally excluded from museums. However, as museums opened up, they saw themselves as places of instruction, not only in terms of knowledge gained about the world but also in terms of desired behavior.[113] The aim was for “the rough and raucous” working class visitors to learn civil behavior by modeling themselves after middle-class codes of behavior that they would have been exposed to during a museum visit.[114] Though this did not necessarily always work in practice, the idea was part of the construction of museums. Modes of public conduct were established and policed through the organization of museum spaces.[115] For example, museum exhibition space was not only arranged in an orderly fashion, controlling the way objects and knowledge were made visible and available to the public, but also controlled people’s behaviors as visitors were watched by each other and by staff. Visiting a museum turned into being “an exercise of civics.”[116] Museums during this period generated their own patterns of exclusion and discrimination of visitors.[117]

During the 19th century to mid-20th century there was an explosion of national museums. This type of museum played a significant role for newly developed and developing nation-states. They were a means for nation-states to exhibit the longevity of their past thus legitimizing their existence in the present and to provide a national culture, while in some cases also representing multiple cultures within one. Moreover, the further back in time a nation could trace its history “the more distinguished the present-nation is.”[118] Through exhibitions national museums attempted to prove continuous occupation of a territory that extended as far back in time as was possible.[119] Furthermore, this type of museum has very political implications as identity/identities are navigated and articulated. National identities as depicted in national museums are formidable “cultural forces” with the pivotal “power to shape political communities.” These identities are viewed as “knowledge-based” and therefore are touted as objective and valid.[120] That said, the national narratives or identities presented are typically that of the majority population that override any divergent narratives or identities.[121] Art and history museums were the primary types of museums for early national museums because they “contribute to the expression, links to, visualization and imagination of the past, present and future.”[122]

Many national museums were built based on existing individual collections. National museums were a way of authorizing the newly formed nation as “collector,” demonstrating their identity and existence as owners of collections. It was a means of stating that the nation was part of an educated group while expressing their individual distinctiveness in addition to stating that they were equal and on par with other nations. Nation-states could demonstrate their possession and mastery of the world through their collections. Colonial powers were especially adept at this as they collected objects and specimens from their colonies and placed them in their own museums, encouraging wholesale looting of the world to fill their museums. Imperialism was also present in many national museums, illustrating the extent that nation-building took place in an empire.[123] National museums were a way of “celebrating the achievements of the empire.”[124] Later, nationalists in colonized countries used the idea of a national museum as they sought independence from their colonizers and established a postcolonial nationality and citizenship.[125]

Archaeological museums became especially meaningful for many nations because of their connection with the distant past. These museums were often supplemented by history museums. These museums aided in creating a national narrative and were in some ways an extension of archaeological museums in tracing the nation’s history into the recent past. Folk history museums were a type of museum that focused on rural, agricultural peasant traditions. They were particularly crucial in countries with a strong peasant tradition in depicting the national narrative. They showcased what was specific to a country’s landscape and architecture and often had a Romantic and nostalgic view of national history.[126] All three types of museums place an emphasis on continuity of history and where discontinuity existed it was important to explain it and find ways to bridge those discontinuities. They similarly exhibited continuous civilizational progress that showed the prominent role of the nation.[127]

Art museums were a significant aspect of exhibiting the nation. Masterpieces illuminated national genius and illustrated events of great national importance. Art was often classified according to national lines. “Nationalized art was supposed to reflect national character.”[128] The public display of this art was to place the distinction of one’s nation against that of others.

Natural history museums exhibited fauna, flora, lakes, and other landscapes according to middle- and upper-class societies’ national imaginations. This was frequently through 0the use of dioramas.[129] During the 19th century, science was used to transform the world and to create authority. “Museums interpreted objects scientifically and presented narratives validated by science. By doing this they themselves claimed authority over the stories contained in their exhibitions.”[130]

Regional museums played noteworthy roles as well. They displayed regional diversity of empires while also demonstrating that these regions were critical building blocks for the formation of nation-states.[131] Regions, with their own cultural, linguistic, ethnic and political specificities, had to be compatible with the nation that they were in. Regional identities were important because nation builders generally understood that they had existed long before national ones. Frequently, regional museums existed before national museums.[132] Some regional or provincial museums later turned into national museums. Provincial museums became part of negotiating relationships between people from the provinces and the central government.[133]

Over the centuries, the development of museums has closely followed the path society has taken, particularly regarding education and the acquisition of knowledge. Displays of one’s social status and power were equally important. Today, museums continue to follow the path of educating the public and building knowledge. Museums continue to seek new ways of engaging audiences, often focusing on significant societal issues such as social justice and equality. They seek to democratize information, making it available to all.

Bibliography

Abt, Jeffery. “The Origins of the Public Museum.” A Companion to Museum Studies, Ed. Sharon Macdonald. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, Ltd., 2006. 115-134.

Alexander, Edward P. “Introduction.” Museum Masters: Their Museums and Their Influence. American Association for State and Local History: Nashville, 1983. 3-15.

______. “What is a Museum?” Museums in Motion: An Introduction to the History and Function of Museums. American Association for State and Local History: Nashville, 1979.: 3-15.

Bennett, Tony. The Birth of the Museum: History, theory, politics. London and New York: Routledge, 1995.

Berger, Stefan. “National Museums in Between Nationalism, Imperialism and Regionalism, 1750-1914.” National Museums and Nation-Building in Europe 1750-2010, eds. Peter Aronsson and Gabrielle Elgenius. Routledge: London and New York, 2015. 13-32.

Blake, Janet. “Cultural Heritage Law: Contextual Issues,” International Cultural Heritage Law. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2015. 1-22.

Elgenius, Gabrielle. “National Museums as National Symbols: A survey of strategic nation-building and identity politics; nations as symbolic regimes.” National Museums and Nation-Building in Europe 1750-2010, eds. Peter Aronsson and Gabrielle Elgenius. Routledge: London and New York, 2015. 145-166.

Findlen, Paula. “The Museum: Its Classical Etymology and Renaissance Genealogy.” Grasping the World: the Idea of the Museum, eds. Donald Preziosi and Claire Farago. Farnham, England and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2004. 159-191.

Hooper-Greenhill, Eilean. Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge. London and New York: Routledge, 1992.

Latham, Kiersten F. and John E. Simmons. “Defining Museums (and Museum Studies).” Foundations of Museum Studies: Evolving Systems of Knowledge. Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited, 2014. 3-21.

______. “The Origins of Museums.” Foundations of Museum Studies: Evolving Systems of Knowledge. Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited, 2014. 23-35.

MacDonald, Sharon. “Collecting Practices.” A Companion to Museum Studies, ed. Sharon MacDonald. Blackwell: Malden, MA, 2006. 81-97.

Pearce, Susan M. “Museums: the Intellectual Rationale,” Museums, Objects, and Collections: A Cultural Study. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institute Press, 1993. 89-117.

______. On Collecting: An investigation into collecting in the European tradition. London and New York: Routledge, 1995.

Simmons, John E. Museums: A History. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016.

Further Reading:

Impey O. and A. MacGregor, eds. The Origins of Museums: The Cabinet of Curiosities in Sixteenth and Seventheenth-Century Europe. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985.

[1] Paula Findlen, “The Museum: Its Classical Etymology and Renaissance Genealogy,” in Grasping the World: the Idea of the Museum, eds. Donald Preziosi and Claire Farago (Farnham, England and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2004), 160.

[2] Susan M. Pearce, On Collecting: An investigation into collecting in the European tradition (London and New York: Routledge, 1995), 96. John E. Simmons, Museums: A History (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016), 1. Jeffery Abt, “The Origins of the Public Museum,” in A Companion to Museum Studies, ed. Sharon Macdonald (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, Ltd., 2006), 115.

[3] Kiersten F. Latham and John E. Simmons, “Defining Museums (and Museum Studies),” in Foundations of Museum Studies: Evolving Systems of Knowledge (Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited, 2014), 3.

[4] Pearce, On Collecting, 97.

[5] Pearce, On Collecting, 97-98.

[6] Kiersten F. Latham and John E. Simmons, “The Origins of Museums,” in Foundations of Museum Studies: Evolving Systems of Knowledge (Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited, 2014), 25.

[7] Latham and Simmons, “Defining Museums,” 3.

[8] Simmons, Museums: A History, 36.

[9] Abt, “The Origins of the Public Museum,” 116.

[10] Abt, “The Origins of the Public Museum,” 116.

[11] Abt, “The Origins of the Public Museum,” 116.

[12] Pearce, On Collecting, 98.

[13] Edward P. Alexander, “What is a Museum?,” in Museums in Motion: An Introduction to the History and Function of Museums (American Association for State and Local History: Nashville, 1979), 8.

[14] Latham and Simmons, “Defining Museums,” 3-4.

[15] Eilean Hooper-Greenhill, Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge. (London and New York: Routledge, 1992), 89.

[16] Information about Thutmosis III from Simmons, Museums: A History, 24.

[17] Abt, “The Origins of the Public Museum,” 117.

[18] Simmons, Museums: A History, 30.

[19] Pearce, On Collecting, 92.

[20] Simmons, Museums: A History, 30.

[21] Abt, “The Origins of the Public Museum,” 118.

[22] Pearce, On Collecting, 92.

[23] Pearce, On Collecting, 92.

[24] Pearce, On Collecting, 93-4.

[25] Pearce, On Collecting, 100.

[26] Pearce, On Collecting, 107.

[27] Simmons, Museums: A History, 47-48.

[28] Simmons, Museums: A History, 63.

[29] Sharon MacDonald, “Collecting Practices,” in A Companion to Museum Studies, ed. Sharon MacDonald (Blackwell: Malden, MA, 2006), 85.

[30] Findlen, “The Museum,” 172.

[31] MacDonald, “Collecting Practices,” 84-5.

[32] Pearce, On Collecting, 110.

[33] Pearce, On Collecting, 111.

[34] Simmons, Museums: A History, 61.

[35] Susan M. Pearce, “Museums: the Intellectual Rationale,” in Museums, Objects, and Collections: A Cultural Study (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institute Press, 1993), 92.

[36] Simmons, Museums: A History, 62.

[37] Abt, “The Origins of the Public Museum,” 120.

[38] Simmons, Museums: A History, 71.

[39] Hooper-Greenhill, Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge, 86.

[40] Alexander, “What is a Museum?,” 8.

[41] Hooper-Greenhill, Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge, 86.

[42] Hooper-Greenhill, Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge, 88.

[43] Simmons, Museums: A History, 64.

[44] Simmons, Museums: A History, 72.

[45] Abt, “The Origins of the Public Museum,” 122.

[46] Pearce, On Collecting, 112.

[47] Hooper-Greenhill, Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge, 105.

[48]Tony Bennett, The Birth of the Museum: History, theory, politics (London and New York: Routledge, 1995), 36.

[49] Bennett, The Birth of the Museum,” 27; Hooper-Greenhill, Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge, 103.

[50] Pearce, “Museums: the Intellectual Rationale,” 93.

[51] Bennett, The Birth of the Museum, 27.

[52] Pearce, On Collecting, 105.

[53] Hooper-Greenhill, Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge, 108.

[54] Pearce, On Collecting, 105.

[55] Simmons, Museums: A History, 77.

[56] Simmons, Museums: A History, 65.

[57] Hooper-Greenhill, Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge, 90.

[58] Simmons, Museums: A History, 73.

[59] Hooper-Greenhill, Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge, 90 and 123.

[60] Simmons, Museums: A History, 66; Pearce, “Museums: the Intellectual Rationale,” 95.

[61] Simmons, Museums: A History, 68-9.

[62] Simmons, Museums: A History, 69.

[63] Pearce, “Museums: the Intellectual Rationale,” 95; Hooper-Greenhill, Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge, 108-109.

[64] Simmons, Museums: A History, 63.

[65] Simmons, Museums: A History, 64.

[66] Hooper-Greenhill, Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge, 112.

[67] Simmons, Museums: A History, 86; Pearce, On Collecting, 112; Hooper-Greenhill, Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge, 88-9.

[68] Simmons, Museums: A History, 86.

[69] Findlen, “The Museum,” 173.

[70] Simmons, Museums: A History, 93.

[71] Simmons, Museums: A History, 93.

[72] Simmons, Museums: A History, 93.

[73] Findlen, “The Museum,” 175.

[74] Alexander, “What is a Museum?,” 8.

[75] Alexander, “What is a Museum?,” 8.

[76] Pearce, “Museums: the Intellectual Rationale,” 99.

[77] Simmons, Museums: A History, 95.

[78] Edward P. Alexander, “Introduction,” in Museum Masters: Their Museums and Their Influence (American Association for State and Local History: Nashville, 1983), 3.

[79] Pearce, “Museums: the Intellectual Rationale,” 99.

[80] Pearce, On Collecting, 124.

[81] Pearce, On Collecting, 124.

[82] Simmons, Museums: A History, 128.

[83] Hooper-Greenhill, Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge, 170.

[84] Pearce, On Collecting, 124.

[85] MacDonald, “Collecting Practices,” 84; Simmons, Museums: A History, 137.

[86] Bennett, The Birth of the Museum, 41.

[87] Bennett, The Birth of the Museum, 41.

[88] Pearce, On Collecting, 127.

[89] Bennett, The Birth of the Museum, 44.

[90] Simmons, Museums: A History, 126.

[91] Pearce, On Collecting, 126.

[92] Bennett, The Birth of the Museum, 36.

[93] Pearce, “Museums: the Intellectual Rationale,” 100.

[94] Simmons, Museums: A History, 98.

[95] Abt, “The Origins of the Public Museum,” 126.

[96] The majority of information in this paragraph comes from Simmons, Museums: A History, 113.

[97] Simmons, Museums: A History, 125.

[98] Abt, “The Origins of the Public Museum,” 128; Hooper-Greenhill, Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge, 172.

[99] Abt, “The Origins of the Public Museum,” 129.

[100] Alexander, “What is a Museum?,” 8.

[101] Abt, “The Origins of the Public Museum,” 129.

[102] Stefan Berger, “National Museums in Between Nationalism, Imperialism and Regionalism, 1750-1914” in National Museums and Nation-Building in Europe 1750-2010, eds. Peter Aronsson and Gabrielle Elgenius (Routledge: London and New York, 2015), 21.

[103] Simmons, Museums: A History, 155.

[104] Information in this paragraph comes from MacDonald, “Collecting Practices,” 88.

[105] Hooper-Greenhill, Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge, 171.

[106] Hooper-Greenhill, Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge, 180-181; Bennett, The Birth of the Museum, 95-96.

[107] Hooper-Greenhill, Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge, 182.

[108] Simmons, Museums: A History, 153.

[109] Information in this paragraph comes from MacDonald, “Collecting Practices,” 87.

[110] Pearce, On Collecting, 133.

[111] Bennett, The Birth of the Museum, 39.

[112] Pearce, On Collecting, 133-134; Bennett, The Birth of the Museum, 39.

[113] Bennett, The Birth of the Museum, 28.

[114] Bennett, The Birth of the Museum, 28.

[115] Bennett, The Birth of the Museum, 101.

[116] Bennett, The Birth of the Museum, 99 and 101-102.

[117] Bennett, The Birth of the Museum, 100.

[118] Berger, “National Museums,” 13.

[119] Gabrielle Elgenius, “National Museums as National Symbols: A survey of strategic nation-building and identity politics; nations as symbolic regimes” in National Museums and Nation-Building in Europe 1750-2010, eds. Peter Aronsson and Gabrielle Elgenius (Routledge: London and New York, 2015), 160.

[120] Elgenius, “National Museums as National Symbols,” 149.

[121] Elgenius, “National Museums as National Symbols,” 148.

[122] Elgenius, “National Museums as National Symbols,” 161.

[123] Berger, “National Museums,” 13.

[124] Berger, “National Museums,” 16.

[125] Berger, “National Museums,” 29; Simmons, Museums: A History, 165.

[126] Berger, “National Museums,” 16.

[127] Information in this paragraph comes from Berger, “National Museums,” 14-16.

[128] Berger, “National Museums,” 16.

[129] Berger, “National Museums,” 18.

[130] Berger, “National Museums,” 18.

[131] Berger, “National Museums,” 22.

[132] Berger, “National Museums,” 25.

[133] Elgenius, “National Museums as National Symbols,” 158.