Tashia Dare

Material culture is about the social relationship between people and things. It is not only about how humans have shaped objects, but also about how objects have shaped humans. When studying material culture there are several questions that archaeologists, anthropologists, historians, art historians, and others seek answers to. Many of the questions are concerned with social dynamics and power structures, wealth and status, religion, politics, symbolism, priorities and interests, tradition, creativity, and ingenuity. These questions focus on identity formation, relationships, experiences, and how these are communicated. They are also concerned with trade and local and long-distance economies. It is about social interactions among different populations and the adoption and adaption of methods and techniques of producing objects. The questions are also about what was meaningful to individuals and groups of people in a particular time and/or space. What did someone think about when they incorporated a specific image, symbol, and/or text on an object? What was their understanding of certain symbols or images? How did they understand what came before them and how do we see them adapt that to their own time and purpose?

Some questions are reflective of us today and what has been passed down over generations. What are people interested in studying and collecting and why? Where objects are located today, such as in museums or private collections, and how they are displayed says much about our views today as well as where we have come from. It speaks to how we have come to understand certain histories and how we categorize or classify material culture, people, and geography. Our perspectives change over time based on the information we learn and our own societal viewpoints. What was classified as one thing in the past may continue to be passed down to us in that manner, but many people today question the underpinnings behind those classifications.

The questions below focus on objects, but many of them may also be applied to built structures that could be considered material culture, such as temples, churches, and other places of worship; houses; historical buildings; and historical or archaeological sites.

- Who made the object? Was the piece commissioned by an individual, a group, or an institution for a specific reason, or did the creator make the object for their own purpose?

- What material is the object made of? How were the colors created? What is the quality of craftsmanship? What was available to the creator and what was their training?

- What is on the object? What iconography (range or type of images) or text is there and why?

- When was the object created? What was happening at the time of production?

- Why was the object made? What purpose did it have? Was it for rituals, practical daily use, or for another purpose? Was there any symbolic meaning given to the object? How did it function?

- Was the object created in one place and moved to another location, whether local or long distance (for example, an amphora produced in Rome but shipped to Asia Minor or Roman Britain)? What does this say about social, cultural, and economic trade; the rise and fall of empires and colonies; imperialism; creativity; ingenuity; adaption; and nature and climate change?

- Where was the object placed within its original setting? Was it in a home, in or on the exterior of a place of worship or another type of building? How was the object supposed to be seen, such as overhead or at eye level? What was the purpose by the creator and/or patron of placing something at that vantage point? Inside a building the same questions can be asked, as well as others. How was the object placed in relation to other objects? Is it in isolation or in a group? Was it placed in a niche or on an altar or was it hanging on a wall or ceiling? How did the creator and/or patron want people to interact with the object(s)?

- Where was the object found? Was it found in its original context or was it found in another location such as in a museum, in a personal collection, or elsewhere?

- When an object is described as art, and art is an early form of technology, we must ask what makes this object art. Was the object considered “art” when it was first created or do we classify it today as art rather than as it originally was intended? Does it have both artistic and practical qualities? How is the object displayed to the public?

For example, there are ancient Greek stelae or urns on display in art museums. While these have artistic qualities, their original function was as a grave marker or as a storage vessel. The same is true for ancient Egyptian sarcophagi. The decorations on these are often intended to help the deceased through the afterlife and to identify the individual. In this case, the decorations both have practical implications for the deceased but are also artistic.

- Concerning the above questions, who has the authority to name or classify material culture at any given time? The creator, the patron, scholars, or another entity? Why that particular person or persons? What is the reason or goal of making such a classification?

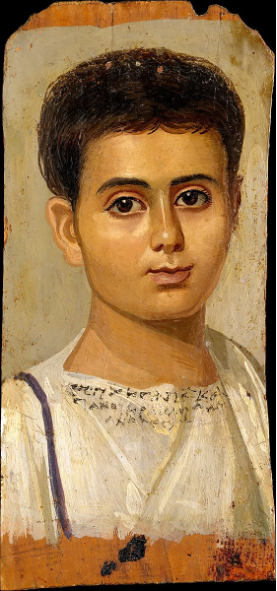

Figure 1. Portrait of the Boy Eutyches, 100–150 CE, Roman Period (30 BCE–323 CE). Encaustic on wood and paint, 38 cm (14 15/16 in.) × 19 cm (7 1/2 in.). New York Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of Edward S. Harkness, 1918, 18.9.2.

In the Roman world portraiture played a significant role as a mode of recording individual appearance and social standing. The portrait genre is an enduring legacy of the Romans that continues to be employed today.[1] From the early first century CE to the third century CE, hundreds of funerary portraits (commonly referred to as mummy portraits) were created for Graeco-Roman elites living in Egypt. These portraits serve not only as a way to memorialize the deceased, but they also record important personal and social identities of the those depicted. They demonstrate the family, religious, cultural, and professional ties of a multicultural and multiethnic Egypt during the Roman Empire (27 BCE–323 CE). The portraits display the interrelations of the Hellenistic (Greek), Roman, and Egyptian worlds.

Prior to the Roman era the Greeks governed Egypt from approximately 332 BCE–27 BCE. One of Alexander the Great’s generals, Ptolemy I, took over Egypt, founding the Ptolemaic Dynasty that ended with the death of the famous Cleopatra VII in 30 BCE. The early settlers in the Greek region of the Fayum Oasis were given land, and many throughout Egypt married native Egyptians.[2] In 27 BCE the Roman Emperor Augustus gained control of Egypt. Greek-speaking residents likely saw themselves as both Greek and Egyptian. It was common in the Roman East to have dual or plural identities, to retain both local identification and pride as well as to take part in metropolitan culture in the Greek regions of the Roman Empire.[3] Roman authorities put the descendants of the early Greek settlers in charge of towns and villages of the Fayum, giving them privileged status and a poll-tax rate reduction.[4] When the Ptolemies and Romans arrived in Egypt they brought with them their language, cultural practices, clothing and hairstyles, and artistic techniques. In turn, they adopted aspects of ancient Egyptian religious beliefs and burial practices. This included the adoption of some Egyptian gods and goddess, notably Osiris and Isis (many Greek and Roman temples were dedicated to Isis). Additionally, like ancient Egyptians before them, many of the elite were mummified and wrapped in linen and then placed in a sarcophagus decorated with Egyptian hieroglyphs and a portrait covering the deceased’s face. Early Roman-Egyptian portraits are particularly lifelike, utilizing Roman verism or naturalism, and are exemplars in Greek painting techniques, while later portraits and funerary masks are less personalized. It is important to note that these portraits are some of the only surviving works of Greek painting. Wet and humid conditions in Greece did not allow much for the preservation of ancient Greek paintings, unlike in Egypt, where the arid environment preserved most organic material.

The funerary portrait of the boy Eutyches is a beautiful example of a Roman-Egyptian funerary portrait (sometimes referred to as a panel) (fig. 1). We can apply many of the questions listed above to this portrait. To begin, who made this portrait? At this point, scholars do not know. Throughout much of the ancient Near East artists usually did not sign their names. Since this portrait is of a child, we can imagine that his parents or at least his father may have commissioned the portrait, although there may have been another individual who commissioned the panel, as noted below. While some scholars suggest that this type of portraiture was commissioned during the lifetime of the individual, in this case it was likely commissioned shortly after the child’s death.

Second is the question of how the portrait was created, what materials were used, and the quality of craftsmanship. While many portraits were painted in tempera, most were produced with encaustic on wood or on linen shrouds. In tempera, the pigments are mixed with a water-soluble agent, usually an animal glue. In encaustic, the pigments are mixed with hot or cold beeswax and other ingredients such as resin, egg, or linseed oil. Brushes and hard tools were used to execute the portrait. Sometimes only a brush was used throughout, while in others we see the use of a brush before a hard tool was utilized to blend colors and to add “wound” marks that create texture and depth.[5] Eutyches’s portrait was created with encaustic directly applied to wood without a distemper ground (a type of whitewash), as evidenced at the top and bottom of the portrait where there is no paint (linen wrappings would have hidden these bare areas).[6] We can see the brushstrokes and the use of a hard tool, especially in Eutyches’s neck and clothes, as well as in the background. The craftsmanship of this portrait is of exceptionally high quality, a symbol of both the painter’s skill as well as the status of the person or persons who commissioned or paid for the panel. The style of painting, which originated in Classical Greece in the fifth and fourth centuries BCE, the shadowing, the modeling of his face, and other features are Greek in nature, while the use of naturalism in depicting the child’s face is Roman.[7] Furthermore, the artist depicts Eutyches’s fleshy face as a golden brown. Having tanned skin was an important social aspect for Greek males.

Next is the question of what is on the object, the iconography and/or text, and why. The depiction of Eutyches’s clothes indicates a Roman affiliation. He wears a white Roman tunic with a narrow purple clavus (a vertical stripe) over the right shoulder and a mantle draped over the left shoulder.[8] Typically, the clavi (plural of clavus) in Rome indicated social rank, but in Egypt it may have demonstrated the individual’s general sense of affiliation with Roman customs.[9] In black or dark purple ink along the neckline of Eutyches’s garment is a Greek inscription. Greek was one of the primary languages in the ancient Mediterranean. Additionally, it is not uncommon to see Greek inscriptions on funerary portraits, which includes the name of the deceased and a short epitaph. These can often be found around the neck area. Other times the identity of the portrayed may appear on the sarcophagus itself, just as ancient Egyptians had previously done with their deceased. Scholars debate over aspects of the inscription on Eutyches’s portrait. What is clear is the boy’s name, “Eutyches, freedman of Kasanios.” What is in question is the rest of the inscription, which either says “son of Herakleides Evandros” or “Herakleides, son of Evandros.” It is also uncertain whether the “I signed” at the end of the inscription indicates the act of manumission (freeing a slave) or is the painter’s signature.[10] It is very uncommon for painters to sign their name on a funerary portrait. In addition, the verb used here is different than what is typically used by artists signing their work.[11] The combination of Eutyches’s Roman clothes and the Greek inscription demonstrate his and possibly his parents’ (or his father’s) plural identity in Egypt.

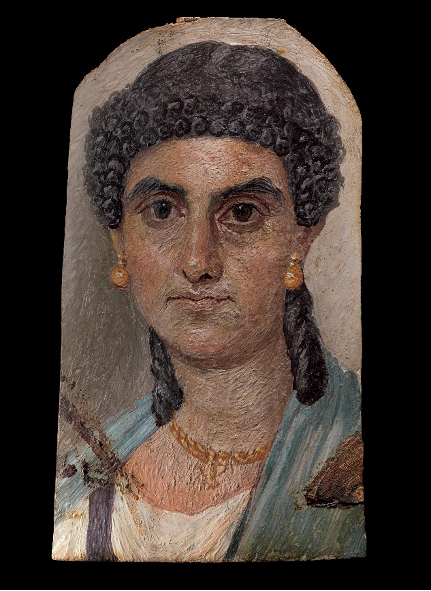

One of the most important questions is when an object was created. This helps scholars to better understand the object they are studying and to place that object in a wider context. For funerary portraits, dating is often based on clothing, hairstyles, and/or women’s jewelry. It also is dependent on the context of where the mummified human remains were found. If they were found within their original location, scholars can date an object based on other objects found with the mummified human remains. This is possible because even in remote parts of the Roman Empire people generally attempted to follow imperial fashion and certain aspects of daily life, such as Latin handwriting and tableware, which were fairly consistent across the empire. In the case of the portraits, many individuals may have been engaged in the local administration on behalf of the empire, which explains the desire to dress like those living in Rome. We also see this in portraits in Syria and Libya of the same time period as the Roman-Egyptian portraits.[12] A great example of dating based on features depicted in the portrait is that of a panel of a young woman wearing a blue mantle (fig. 2). Scholars date this portrait to Emperor Nero’s reign (54–68 CE) based on the woman’s hairstyle, which is modelled after Nero’s mother, Agrippina. Eutyches’s portrait dates to 100–150 CE, during Trajan, Hadrian, or Antoninus Pius’ reigns. Scholars date this portrait based on his clothing, the orderliness of his hair, and by the high quality of the portraiture.[13]

Another important question is why an object was created and what its purpose was. As previously noted, Roman-Egyptian funerary portraits were created to record an individual’s personal and social identities. Scholars debate whether the funerary portraits were produced during the lifetime of the individual depicted or posthumously. If they were created during the lifetime of the individual, then the image would have been placed within the person’s home, likely hanging on a wall as a reminder to any viewer of the cultural and social status of the person. It is much like what people have done over the centuries who have had their portraits painted or their picture taken. Upon death, the Roman-Egyptian portraits would have been cut in the upper corners to fit over the face of the mummified body within a sarcophagus and inserted into linen wrappings. Portraits may have been processed (ekphora) along with the body through the hometown or village of the deceased before being taken to embalmers to be mummified.[14] The ekphora was a Greek rite. It was custom to keep mummies of loved ones in the home or in a chapel for quite a length of time, which also allowed family members and others to view the portrait and remember that person. The Roman practice of the Cult of the Ancestor was significant throughout the empire and was related to the above custom. On the other hand, some portraits were painted at the time of death, notably those of children. In the case of Eutyches, his death may have been unexpected and thus his parents (or his father) or Kasanios, who freed Eutyches, commissioned the portrait after his death as a means of memorializing him and his place within society.[15] Slavery in ancient Rome was different than we understand slavery today. Individuals could be freed by their owners or buy their own freedom. We do not know what the situation was for Eutyches. If his parents, or specifically his father, commissioned the portrait, that may also be a sign of his parents’ or his father’s status in Egypt at the time and indicate the socio-economic situation Eutyches would have grown up in and what he would have been expected to be as an adult. However, if Kasanios commissioned the portrait, that demonstrates his position in local society and may also indicate his love for Eutyches, almost as if he was his own son.

The provenance, or origin, of this portrait is unknown. One source suggests that it may originate from the Philadelphia area because the name Kasanios was popular in the area during the second century CE.[16] Philadelphia is in the Fayum Oasis region. The Fayum is where many funerary portraits were found, although several others have been found in Middle Egypt and as far north as near Alexandria. Another source suggests the portrait is from Antinoöpolis, which is in Middle Egypt, although this is in question.[17] Regardless, the portrait would likely have been produced locally rather than having been made in a distant city. The materials used to create the portrait would also likely have been available locally.

Today, many funerary portraits are in museums, specifically art museums, either on display or in storage. The majority of portraits were discovered by archaeologists in the late nineteenth to early twentieth centuries, although several were found much earlier and more recently. Some portraits were found with their mummified human remains and were preserved intact, while others had been previously detached from the mummified human remains, such as that of Eutyches. In some cases, the mummified human remains to which the portrait was attached either were not preserved or were discarded completely, as the portrait was viewed as being more valuable. While today we view the portraits as works of art, we also must remember that these portraits in their time had very real implications for the individuals portrayed and for their families. They were created to record a person’s personal, social, cultural, and religious identities and were a reminder to anyone seeing the portrait, whether in the home where it was hung on the wall or before burial, who this person is and was. Furthermore, in death, the portraits serve to immortalize and memorialize the individual. Consequently, the people depicted in these portraits must be viewed by us with respect, as any human being deserves. For us today, these portraits are beautiful works of art that give us a glimpse into the lives of those living in Egypt and in the Roman empire nearly 2,000 years ago.

Figure 2. Panel painting of a woman in a blue mantle, 54–68 CE, Roman Period (30 BCE–323 CE). Encaustic on wood, 38 cm (14 15/16 in.) × 22.3 cm (8 3/4 in.). New York Metropolitan Art Museum. Director’s Fund, 2013, 2013.438.

Bibliography

Doxiadis, Euphrosyne. The Mysterious Fayum Portraits: Faces from Ancient Egypt. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1995.

Campbell, Thomas P. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Guide. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012.

“Portrait of the Boy Eutyches.” Metropolitan Art Museum. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/547951?searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&where=Egypt&ft=mummy+portrait&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=2; and Susan Walker and Morris Bierbrier, with Paul Roberts and John Taylor. Ancient Faces: Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt. London: British Museum Press, 1997.

Further Reading:

Bierbrier, Morris L. Portraits and Masks: Burial Customs in Roman Egypt. London: British Museum Press, 1997.

Borg, Barbara E., and G. W. Most. “The Face of the Elite (Complexities of Cultural Identity Illustrated by Mummy Portraits from Graeco-Roman Egypt).” Arion: A Journal of Humanities and Classics 8, no. 1 (2000): 63–96.

Geoffroy-Schneiter, Bérénice. Fayum Portraits. New York: Assouline, 2004.

Montserrat, Dominic. Sex and Society in Graeco-Roman Egypt. London: Kegan Paul International, 1996.

Montserrat, Dominic. “Your Name Will Reach the Hall of the Western Mountains”: Some Aspects of Mummy Portrait Inscriptions.” Archaeological Research in Roman Egypt: The Proceedings of the Seventeenth Classical Colloquium of the Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities, British Museum, held on 1–4 December 1993. Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series Number 19, ed. Donald M. Bailey, 177–86. Ann Arbor, MI: Thomson-Shore, 1996.

Riggs, Christina. “Facing the Dead: Recent Research on the Funerary Art of Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt.” American Journal of Archaeology 106, no. 1 (2002): 85–101.

Thompson, David L. Mummy Portraits in the J. Paul Getty Museum. Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1982.

[1]. Susan Walker and Morris Bierbrier, with Paul Roberts and John Taylor, Ancient Faces: Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt (London: British Museum Press, 1997), 14.

[2]. Walker and Bierbrier, Ancient Faces, 15.

[3]. Walker and Bierbrier, Ancient Faces, 20.

[4]. Walker and Bierbrier, Ancient Faces, 15.

[5]. Walker and Bierbrier, Ancient Faces, 22.

[6]. Euphrosyne Doxiadis, The Mysterious Fayum Portraits: Faces from Ancient Egypt (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1995), 33.

[7]. “Portrait of the Boy Eutyches,” Metropolitan Art Museum,

[8]. “Portrait of the Boy Eutyches.”

[9]. Walker and Bierbrier, Ancient Faces, 16.

[10]. “Portrait of the Boy Eutyches.”

[11]. Walker and Bierbrier, Ancient Faces, 116.

[12]. Walker and Bierbrier, Ancient Faces, 14.

[13]. Walker and Bierbrier, Ancient Faces, 116.

[14]. Walker and Bierbrier, Ancient Faces, 15.

[15]. Thomas P. Campbell, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Guide (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012), 59.

[16]. Doxiadis, The Mysterious Fayum Portraits, 33.

[17]. Walker and Bierbrier, Ancient Faces, 116.