Richard McGaha

Figure 1. Early Cannon from Walter de Milemete’s De Nobilitatibus Sapientii Et Prudentiis Regum Manuscript, 1326. Wikimedia Commons.

By the fourteenth century Europe was on the cusp of a revolution in warfare, one that would have a profound impact on war and the state. The utilization of gunpowder as a military weapon along with the invention of the gun would profoundly alter Europe. The English philosopher Francis Bacon (1561–1626) ranked gunpowder weapons alongside printing and the compass as the three critical discoveries of humankind.[1]

The first unequivocal description of a cannon is a Florentine document dating to 1326 authorizing the manufacture of brass cannon and iron cannonballs. Cannon technology spread quickly across Europe, first being used on the battlefield in 1340.[2]

While early cannon were ineffective tactically, they were effective psychologically. (See fig. 2) At the Battle of Crècy in 1346 the English king Edward III (1312–1377) “struck terror into the French Army with five or six pieces of cannon, it being the first time they had seen such thunderous machines.”[3] While cannon may have been ineffective on the battlefield they did prove their worth in siege operations. Sieges had been an important part of warfare from ancient times. An effective fortification could keep an enemy occupied until either the castle or keep fell or the enemy had to retreat because winter was approaching. Sieges in the ancient and medieval world were incredibly time-consuming.[4] At the siege of Harfleur in 1415 Henry V (1386–1422) used twelve cannon to force the town to surrender. The defenders told him that “he schuld make his gunneres to sese, for it was to [t]hem intollerabil.”[5]

Figure 2. Cannon at the Siege of Orleans from Les Vigiles de Charles VII, manuscrit de Martial d’Auvergne, ca. 1484. Wikimedia Commons.

Early cannon were incredibly heavy and could only be transported easily by sea or on rivers. It was only with difficulty that cannon could be transported overland given the poor road conditions in Europe. Some cannon were cast on the spot of sieges with workshops, men and materials transported to the site. A good example is the siege of Constantinople in 1453, where Sultan Mehmed II (1432–1481) had cannon cast on site for use against the city.[6] Casting cannon on site was incredibly expensive as it required the building of workshops and forges to cast the cannon. It also required the movement of raw materials to the battlefield which required the creation of a logistical train.

Early cannon suffered from several limitations. First, metallurgy was not refined enough to make an iron cannon solid enough to withstand the pressure of exploding gunpowder. Firing a cannon could be hazardous to the operator with the very real risk of the cannon exploding. Some smaller and mid-size iron cannon were wrapped in leather straps so that if the barrel ruptured, the pieces would not fly off and kill or injure the gunners. Larger cannon were cast in bronze. While bronze was stronger than iron, it was also three times more expensive, although the benefits justified the expense.

Second, early gunpowder was not powerful enough to show the true potential of cannon. It was not until the 1420s that “corned powder” was developed. It had larger granules which meant it was faster burning, 30 percent more powerful and resistant to moisture.[7] Early cannon also fired arrows or stones that had been chiseled down to fit the barrel of the cannon. This required access to a ready supply of stone to use as cannonballs which were generally transported to the siege site. The introduction of standard iron cannonballs in the fifteenth century alleviated this concern. Iron cannonballs combined with corned powder and improved metallurgy were more effective at penetrating fortress walls than stone cannonballs.[8] By the end of the fifteenth century cannon had become powerful enough and mobile enough to cause European warfare to change in the early modern period.

Fortresses

Figure 3. Magnus Manske, Muiden Castle. (CC BY-SA 2.0)

The standard castle in the medieval period was made of high stone walls with towers on the four corners surrounded by a moat which was basically a water-filled ditch. (See fig. 3) Indeed, in the Middle Ages, this was the standard design of castles, which was more than adequate for the age. The moat prevented an attacker from digging and undermining the integrity of the wall. Stone was resistant to most weapons of the age, including trebuchet which were basically catapults designed to hurl stones over walls. The height of the walls gave several advantages to a defender. First, the defender could throw down objects at attackers. Second, an attacker had to either build assault towers to roll up to the wall or put up ladders to allow their men to scale the walls. Assaulting a medieval castle was a costly and time-consuming effort. Cannon made those castle designs obsolete almost overnight and turned the advantage back to the attacker.[9]

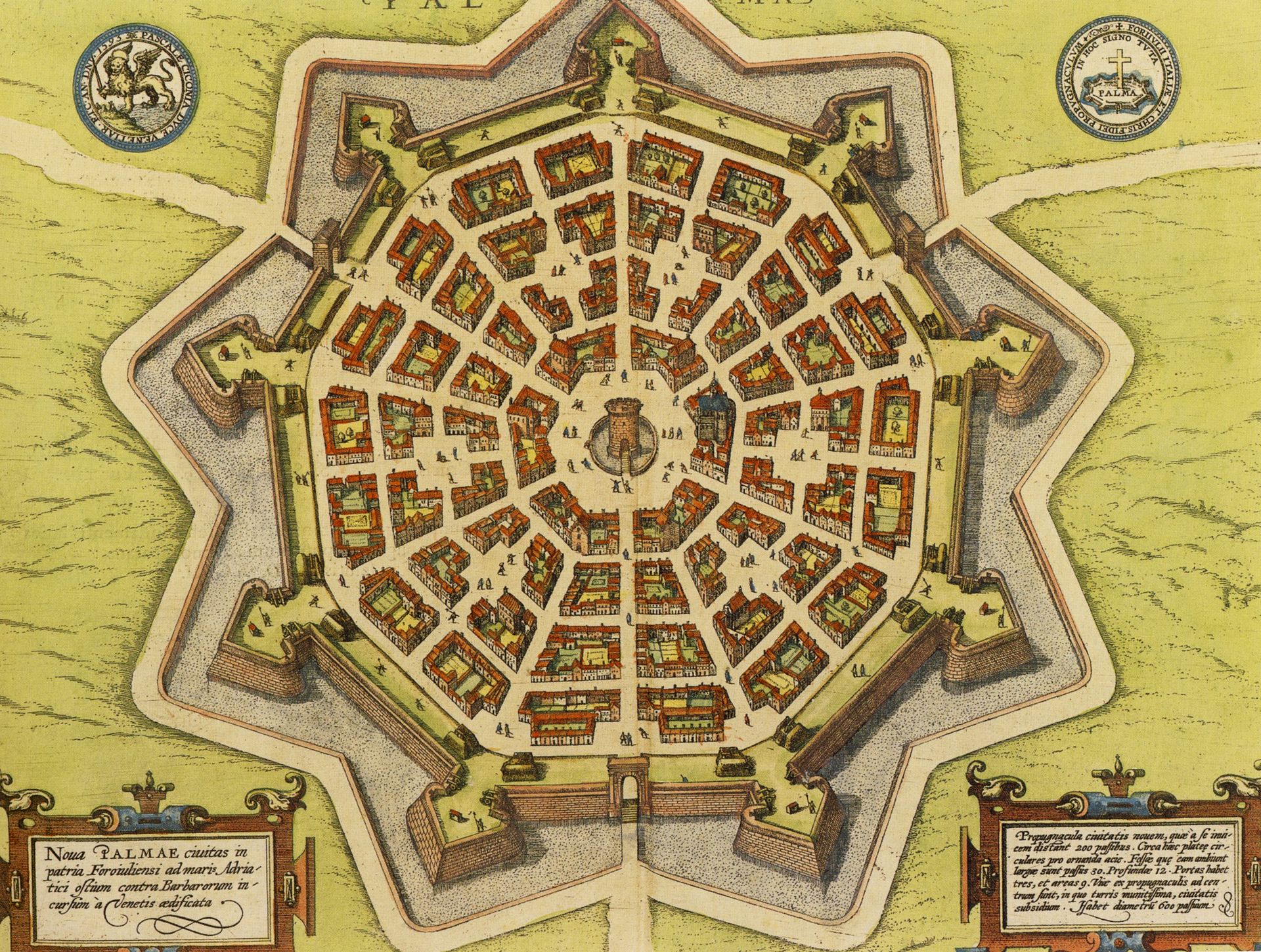

The impetus for this change happened in the constantly warring Italian peninsula during the late fifteenth century. Charles VIII of France (1470–1498) invaded Italy in 1494 with an army of 18,000 men and forty siege guns. As the military historian Geoffrey Parker points out, “even contemporaries realized that this marked a new departure in warfare.”[10] The Italian city-states scrambled to find a way to counter this potent new threat. Their solution was a fortress that became known as the trace italienne. (See fig. 4) Instead of building higher walls the walls were instead lowered and made thicker. Since this made them vulnerable to a surprise attack, flanking fire was needed, and as a result the bastion was developed. The bastion was an angled quadrilateral that jutted out from the main wall of a fortification, which allowed defenders to see every part of the wall and eliminated the blind spots that straight walls and round turrets contained. Bastions also provided mutually supporting fields of fire that caught attackers in a deadly crossfire. Over time, artillery was put on bastions to keep enemy siege guns as far away as possible. A ditch or moat was put around the wall to make it more difficult to undermine the wall. These star-shaped forts allowed a fortress to control up to fifty square miles (eighty square kilometers) of territory.[11]

Figure 4. Palmanova Trace Italienne Fortress ca 1600 from Civitates Orbis Terrarum. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Palmanova1600.jpg Wikimedia Commons.

The cost of these new fortresses was staggering. Smaller city-states and cash- strapped monarchs struggled to pay for these fortresses and ensure their continued survival. Constructing and garrisoning fortresses became the state’s single biggest expense. For example, in the early sixteenth century the Papal States planned a series of eighteen trace italienne style fortresses to protect Rome. The plan was scrapped when it was discovered that the cost of a single fortress was 44,000 ducats—the modern equivalent of 6.6 million dollars. To show how much that was, Venice, easily one of the most powerful city-states on the Italian peninsula had an annual income of 1,150,000 ducats. Siena, another powerful city-state was annexed by Florence when it could not afford to complete the fortifications it had started to build.[12]

In such an environment the state, such as it was in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, was the only body capable of building and financing trace italienne style fortresses in the numbers needed to protect their territory. By promising protection to local lords in exchange for subservience, the early modern nation-states were able to collect taxes to finance their military needs. This led to the creation of a bureaucracy to manage the size of the newly emerging “fiscal-military state.”[13] The consolidation of power and resultant monopoly on violence led to the creation of the modern nation-state. In the words of historian Charles Tilly, “war made the state, and the state made war.”[14] It should be noted that this is not a universally held view and the idea of a technologically driven “military revolution” has drawn some criticism. As historian Steven Gunn points out, there are “those who think war hindered or perverted processes of state formation based on the rule of law, the realization of an ideal model of sovereignty, or the construction of social coalitions based on religious or moral interests.”[15]

The Israeli political scientist Azar Gat and English historian Jeremy Black have argued that the “military revolution” was preceded by political change instead of the reverse. Gat argues that the increase in army size and cost is illusory when compared to the rise in European population during the early modern period. Even Louis XVI’s (1754–1793) massive army of 500,000 was only about 2.5 percent of the total French population which is estimated to have been 20 million. Black argues that only a modern nation-state could have “formed the political pre-condition for military growth.” [16]

In some ways the arguments described above are a chicken-or-egg conundrum. The emergence of firearms and trace italienne style fortresses in the fifteenth century would bring a period of warfare to Europe that would continue almost unabated until 1815. Cannon added a new element ushering in the development of new types of fortresses as well as the creation of governmental bureaucracies to support the armies formed during this period.

[1]. Geoffrey Parker, The Military Revolution: Military Innovation and the Rise of the West 1500-1800 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 160.

[2]. Ian V. Hogg, A History of Artillery (London, Hamlyn Publishers, 1974), 14–15.

[3]. Hogg, A History of Artillery.

[4]. Kelly DeVries and Robert Douglas Smith, Medieval Military Technology, 2nd ed. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012), 165–67.

[5]. Clifford J. Rogers, “The Military Revolutions of the Hundred Years War,” in Clifford J. Rogers, ed., The Military Revolution Debate: Readings on the Military Transformation of Early Modern Europe (Boulder, CO,: Westview Press, 1995), 65–66.

[6]. Parker, The Military Revolution, 7; and Roger Crowley, 1453: The Holy War for Constantinople and the Clash of Islam and the West (New York: Hachette Books, 2006), 90–92.

[7]. For a good discussion of early cannon and technology see Hogg, A History of Artillery, particularly chapters one and two; and Crowley, 87–88.

[8]. Simon Pepper and Nicholas Adams, Firearms and Fortifications: Military Architecture and Siege Warfare in Sixteenth Century Siena (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986), 8.

[9]. See Parker, The Military Revolution, particularly chapter one.

[10]. Parker, The Military Revolution, 9; and Michael Mallett, “Diplomacy and War in Later Fifteenth Century Italy,” Proceedings of the British Academy, 67 (1982), 270.

[11]. J. R. Hale, “The Early Development of the Bastion: An Italian Chronology, c. 1450–c. 1534,” in John Hale, Roger Highfield and Beryl Smalley, eds., Europe in the Late Middle Ages (London: Faber & Faber, 1965), 466–94 and Parker, The Military Revolution, 11.

[12]. Parker, The Military Revolution, 12, 39; and Roger Crowley, City of Fortune: How Venice Ruled the Seas (New York: Random House, 2013), ch. 16.

[13]. This was a state whose only function was national defense and who devoted all of its resources to the military. See especially the argument of Jan Glete in War and the State in Early Modern Europe: Spain, the Dutch Republic and Sweden as Fiscal-Military States (London: Routledge, 2001).

[14]. This is the thesis of Charles Tilly’s, Coercion, Capital and European States, AD 990–1992 (London: Wiley-Blackwell, 1992).

[15]. Steven Gunn, “War and the Emergence of the State: Western Europe, 1350-1600,” in Frank Tallett and D.J.B. Trim eds, European Warfare, 1350-1750 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 50.

[16]. For Gat’s argument see Azar Gat, War in Human Civilization (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 466–71 and 474–76. The quote is from Geoffrey Parker, “In Defense of the Military Revolution,” in Rogers, The Military Revolution Debate, 340. Black’s argument can be found most prominently in “A Military Revolution? A 1660-1792 Perspective,” in Rogers, The Military Revolution Debate, ch 4. Wayne E. Lee also has a valuable discussion of the critiques of the military revolution in Wayne E. Lee Waging War: Conflict, Culture and Innovation in World History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 244–47.