Karen Garvin

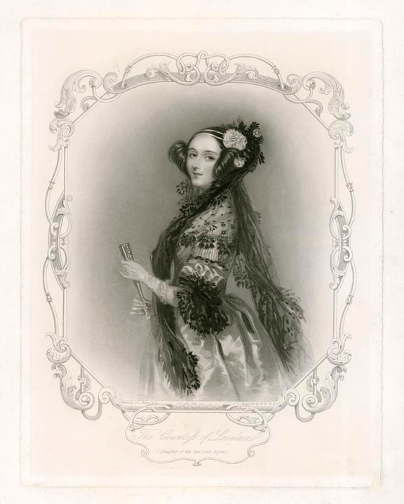

Ada King, Countess of Lovelace (1815–1852), was an English mathematician who collaborated with the mathematician Charles Babbage (1791–1871), the inventor of the mechanical analytical engine. Although Babbage’s intent was to use the machine for arithmetic calculations, Ada realized that by using numbers to represent more than just quantities the analytical engine could become a computing machine instead of a mere computational device. Her analysis led to her being credited with inventing the first computer program.

Ada Lovelace was born Augusta Ada Byron (1815–1852), on December 10, 1815, in Piccadilly Terrace, Middlesex, now part of the city of London.[1] Her parents were the poet Lord George Gordon Byron (1788–1824) and Lady Byron, Anne Isabella Milbanke (1792–1860), who was nicknamed Annabella.

A few weeks after Ada’s birth, her mother separated from Byron because of his ongoing extramarital affairs. For financial reasons, she took Ada and went to stay with her parents in Leicestershire. Initially Lady Byron remained affectionate toward Byron and wrote letters to him, but eventually she sought a legal separation from her husband and was awarded custody of Ada. Meanwhile, Lord Byron had run up considerable debt. He fled the country for Continental Europe, sailing from Dover in April 1816, just barely ahead of the debt collectors.[2] Byron never returned to England.

Despite the scandal created by the couple’s breakup, Lady Byron did all she could to shield her daughter from the worst of it.[3] Lady Byron was well educated and strongly believed that her daughter should receive a good education.[4] From age four, Ada was homeschooled in topics that included geography, mathematics, music, and French. Lady Byron, fearful that Ada might inherit some of her father’s worst tendencies, insisted that Ada be tutored in mathematics because she believed that the rigors of studying the subject would dampen any wild imaginings that Ada might be prone to. Consequently, Ada was closely supervised during her early years to ensure that she develop self-control and learn to be a dutiful child. Ada was often ill during her childhood with severe headaches, and for a while she was prevented from continuing her studies.[5]

Meanwhile, Lord Byron had become involved in the Greek War of Independence from Turkey and died from fever on April 19, 1824. Freed from her former husband’s constraints over what she could do with Ada, Lady Byron was now able to take her daughter on a Grand Tour of Europe. Mother and daughter sailed for the Continent in June 1826, returning to England fifteen months later during the fall of 1827.[6]

After their return, Lady Byron rented a country house called Bifrons, located about sixty miles from London. She was away much of the time, and during her absence Ada became fascinated with the idea of flying. She envisioned a steam-powered winged horse and wrote to her mother about the idea. Lady Byron reacted to this outburst of imagination by immediately hiring a very expensive mathematics tutor for her daughter.[7]

On May 10, 1833, Ada was presented at court to King William IV and Queen Adelaide.[8] At this time, Ada was considered to be an adult woman of marriageable age, and as such, was eligible to attend society functions.[9]

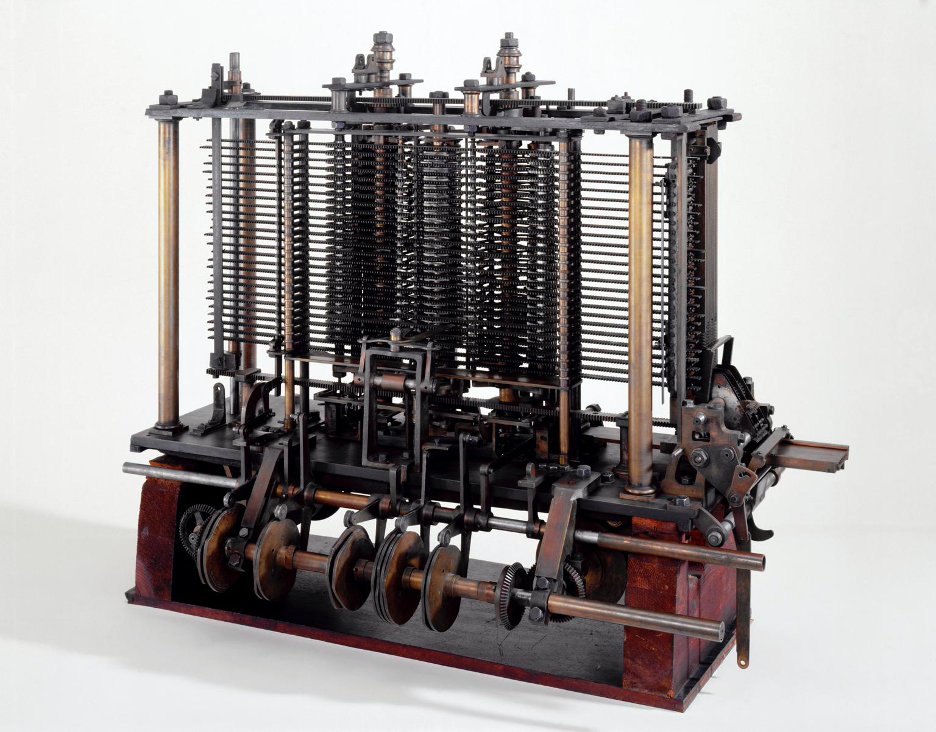

In early June 1833, Lady Byron and Ada were introduced to the scientist Charles Babbage at a society gathering. Babbage enthusiastically described his ideas for a calculating machine to them, which he called the Difference Engine, and invited them to see the prototype of the device.[10] Lady Byron and Ada duly visited Babbage’s London home on June 17, where Babbage’s machine, which Lady Byron referred to as a “thinking machine,” was on display.[11] The machine used cogwheels arranged in vertical columns to represent numbers. When the gears turned, they carried out a mathematical calculation. Ada immediately understood the mathematics involved and became fascinated by the idea that she could write an algorithm to “program” Babbage’s machine, which was in essence an early mechanical computer.[12]

Around this time, Dr. William Frend, who had taught mathematics to both Lady Byron and Ada, introduced them to Mary Somerville, an accomplished mathematician and astronomer and one of the first woman members of the Royal Astronomical Society.[13] By the spring of 1834, Ada and her mother had established a friendship with Babbage and Somerville and they began attending Babbage’s fashionable Saturday evening events, which attracted a wide range of intellectuals.[14] Babbage encouraged Ada to continue to pursue mathematics, so Ada worked with Somerville until 1838 and later studied with the mathematician and logician Augustus De Morgan.[15]

Later that year, Lady Byron began looking for a suitor for Ada. Insisting that her daughter marry an aristocrat, in the spring of 1835 Lady Byron introduced the nineteen-year-old Ada to thirty-year-old William King-Noel, and after a short courtship they were married on July 8, 1835. The couple had three children, Byron (1836), Ralph Gordon (1839), and Anne Isabella (1837). In 1838, William was made the first Earl of Lovelace and Viscount Ockham, and Ada became the Countess Lady Lovelace.

In December 1834, Babbage introduced a new invention that he called the Analytical Engine. Unlike its predecessor, this machine did not need to be manually reset for each new calculation, and it was not hampered by rounding errors. Babbage intended the machine to be programmed with punch cards modeled on those used with Jacquard looms.[16] This loom, invented by French weaver Joseph-Marie Jacquard (1752–1834) and patented in 1804, used interchangeable cards with small holes punched in them to control the raising and lowering of warp threads during the weaving process, which allowed for highly detailed textile designs that could be inexpensively mass produced.[17]

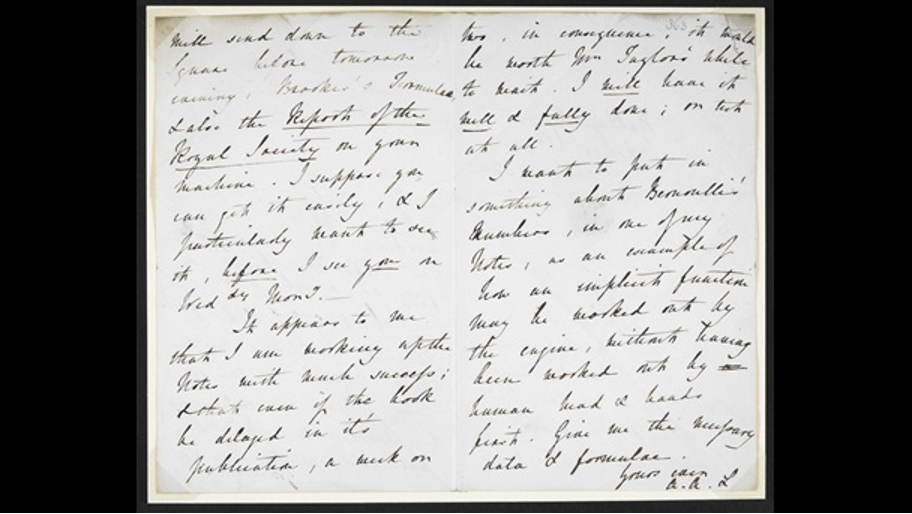

In 1842, the inventor and scientist Charles Wheatstone (1802–1875) approached Ada and asked her to translate a scientific article about Babbage’s machine, written in French by the Italian engineer Luigi Federico Menabrea (1809–1896). Entitled “Notions sur la machine analytique de Charles Babbage,” (“Elements of Charles Babbage’s Analytical Machine”), Menabrea’s article had appeared in the October 1842 edition of the Bibliothèque Universelle de Genève. Ada embraced the challenge and began work immediately. However, when she spoke to Babbage about her work on the translation, he inquired why she had not written an original paper.[18]

The thought had simply not occurred to Ada. At the time, few women wrote for scientific publications; most who dabbled in science aimed their work at a nonprofessional female audience and stuck to explaining concepts and discoveries made by men.[19] Babbage suggested that Ada write and publish her own notes on Menabrea’s article—a task for which Ada was highly qualified, but one that would put her in the novel position of being a woman writing for a male scientific audience.[20]

Ada’s copious notes were very detailed, and she explained how Babbage’s analytical engine differed from his earlier construct, the difference engine. She completed the translation within a few months, but the notes took her nearly a year to complete and during that time she corresponded regularly with Babbage.[21] Finally, in 1843 her translation and notes were published in Taylor’s Scientific Memoirs, a series of books published between 1837 and 1852 that contained collections of scientific papers translated into English.

Ada’s translation of Menabrea’s article ran for 25 pages, but her own “Notes by the Translator” section was more than 40 pages long and offered extensive explanations. In it, she discussed the possible uses of computing machines and provided a set of instructions, or algorithm, for programming them.[22] While Ada published the paper using her initials rather than her full name, she was quickly discovered to be the author, which unfortunately led to the article being taken less seriously than it might have been if she had been a male author.[23]

For the rest of her life, Ada, whom Babbage had called the “Enchantress of Number,” maintained an interest in mathematics, but she was also intrigued by philosophy and other scientific discoveries of the era, including mesmerism. Mesmerism was a form of hypnosis (also known as animal magnetism) promoted by the German doctor Franz Mesmer (1734–1815), who believed it had curative properties. Ada also wanted to try her own hand at practical science and even contacted Michael Faraday (1791–1867) about the possibility of repeating some of his experiments.[24]

By the late 1840s, though, Ada’s health was in decline. Over the summer of 1851 she began to exhibit symptoms of uterine cancer, including heavy bleeding.[25] Ada took laudanum and other drugs to relieve her bouts of pain, but they did nothing to stem the progress of the disease. She died on November 27, 1852, and was buried in the family vault at Hucknall Torkard in Nottinghamshire.

Ada’s mathematical insights, combined with her flair for language (skills that she inherited from both parents), allowed her to make significant contributions to the early field of computer science through her programming ideas and her ability to explain the mathematics behind them.

During the late 1970s, the U.S. Department of Defense wanted a standard programming language for use in military systems. A new language was created, DoD-1, which was later renamed Ada. In 1982, the Association for Women in Computing established the Ada Lovelace Award to honor women working in the computing field for technical achievement and extraordinary service to the computing community.

Further Reading:

Charman-Anderson, Suw. “Ada Lovelace: Victorian Computing Visionary,” Ada User Journal 36, no. 1 (March 2015): 35–41.

Elliott, Francesca. “Weaving Numbers: The Jacquard Loom and Early Computing.” Science and Industry Museum (Manchester), October 17, 2017. https://blog.scienceandindustrymuseum.org.uk/weaving-numbers-jacquard-loom-early-computing/.

Essinger, James. Ada’s Algorithm: How Lord Byron’s Daughter Ada Lovelace Launched the Digital Age. New York: Melville House, 2014.

Hollings, Christopher, Ursula Martin, and Adrian Rice. Ada Lovelace: the Making of a Computer Scientist. Oxford: Bodleian Library, 2018.

Hollings, Christopher, Ursula Martin, and Adrian Rice. “The Early Mathematical Education of Ada Lovelace,” Journal of the British Society for the History of Mathematics 32, no. 3 (2017): 221–34.

Hollings, Christopher, Ursula Martin, and Adrian Rice. “The Lovelace–De Morgan Mathematical Correspondence: A Critical Re-Appraisal,” Historia Mathematica 44 (2017): 202–31.

Kim, Eugene Eric, and Betty Alexandra. “Ada and the First Computer.” Scientific American, May 1999: 76–81.

Lovelace, Ada. “Notes by the Translator,” in Scientific Memoirs, Selected from the Transaction of Foreign Academies of Science and Learned Societies and from Foreign Journals, vol. 3, ed. Richard Taylor London: Richard and John E. Taylor, 1843: 691–731, https://archive.org/details/scientificmemoir03memo.

Taylor, Brian W. “Annabella, Lady Noel-Byron: A Study of Lady Byron on Education,” History of Education Quarterly 38, no. 4 (Winter 1998): 430–55.

Toole, Betty Alexandra Toole, ed. Ada, the Enchantress of Numbers: A Selection from the Letters of Lord Byron’s Daughter and Her Description of the First Computer. Mill Valley, CA: Strawberry Press, 1992.

Woolley, Benjamin. The Bride of Science: Romance, Reason, and Byron’s Daughter. London: Macmillan, 1999.

[1]. James Essinger, Ada’s Algorithm: How Lord Byron’s Daughter Ada Lovelace Launched the Digital Age (New York: Melville House, 2014), 30; Kara Rogers, “Ada Lovelace, British Mathematician,” Encyclopædia Britannica, n.d., https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ada-Lovelace.

[2]. Essinger, Ada’s Algorithm, 5, 33; Benjamin Woolley, Ada Lovelace, The Bride of Science: Romance, Reason and Bryon’s Daughter (London: Pan Books, 2015), 81.

[3]. Essinger, Ada’s Algorithm, 33.

[4]. Brian W. Taylor, “Annabella, Lady Noel-Byron: A Study of Lady Byron on Education,” History of Education Quarterly 38, no. 4 (Winter 1998): 446; Essinger, Ada’s Algorithm, 35–36.

[5]. Woolley, Ada Lovelace, 88; Essinger, Ada’s Algorithm, 43–44.

[6]. Woolley, Ada Lovelace, 109; Essinger, Ada’s Algorithm,4 9–51.

[7]. Essinger, Ada’s Algorithm, 3, 51–55.

[8]. Woolley, Ada Lovelace, 132.

[9]. Essinger, Ada’s Algorithm, 79–80.

[10]. Essinger, Ada’s Algorithm, 81, 85.

[11]. Woolley, Ada Lovelace, 129–30.

[12]. Essinger, Ada’s Algorithm, 87–90.

[13]. Essinger, Ada’s Algorithm, 62, 121; Rubenstein Library, “Guide to the Ada Lovelace Letter, August 5, [1841 or 1847],” Historical Note, Duke University Libraries, https://library.duke.edu/rubenstein/findingaids/lovelaceada/#historicalnote; Woolley, Ada Lovelace, 136.

[14]. Essinger, Ada’s Algorithm, 143; Woolley, Ada Lovelace, 128.

[15]. Essinger, Ada’s Algorithm, 134; Wooley, Ada Lovelace, 200.

[16]. Essinger, Ada’s Algorithm, 114–16.

[17]. “Programming Patterns: The Story of the Jacquard Loom,” Science and Industry Museum (Manchester), June 25, 2019. https://www.scienceandindustrymuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/jacquard-loom.

[18]. Woolley, Ada Lovelace, 259–60.

[19]. Woolley, Ada Lovelace, 260.

[20]. Essinger, Ada’s Algorithm, 192.

[21]. Woolley, Ada Lovelace, 259–60.

[22]. Ada Lovelace, “Notes by the Translator,” in Scientific Memoirs, Selected from the Transaction of Foreign Academies of Science and Learned Societies and from Foreign Journals, vol. 3, ed. Richard Taylor (London: Richard and John E. Taylor, 1843): 691–731, https://archive.org/details/scientificmemoir03memo.

[23]. Essinger, Ada’s Algorithm, 192.

[24]. Woolley, Ada Lovelace, 307–08.

[25]. Essinger, Ada’s Algorithm, 207.