Karen Garvin

Nikola Tesla (1856–1943) was a Serbian American inventor whose major works included designing and building an alternating current (AC) induction motor and developing and promoting a workable AC power distribution system. His interests ran the gamut from alternating current and motors to wireless power and communication, radio control, radar, and even early robotics.

Tesla was an eccentric genius and visionary, yet this “underappreciated mastermind” is less well-known today than his one-time employer and rival, Thomas Edison (1847–1931).[1] Whereas Edison had a systematic approach to inventing, Tesla was less methodical, and was often criticized by his contemporaries for making vague statements about his projects, many of which were considered to be impractical.[2]

Despite being a prolific inventor with more than three hundred patents to his name, Tesla was a poor businessman. He tore up what could have been a lucrative royalty contract with George Westinghouse (1846–1914) and signed over control of lighting patents to J. P. Morgan (1837–1913).[3] A dreamer and idealist, as Tesla aged he became increasingly distant from people, and in his later years developed a phobia of germs that led him to become even more isolated.[4]

Tesla was born at the stroke of midnight on July 10, 1856, during a thunderstorm.[5] His birthplace was Smiljan, Serbia, a part of the Austrian Empire that later became Croatia. Tesla was the fourth of five children of Milutin Tesla, an Eastern Orthodox parish priest, and Djuka Tesla. In 1863, Tesla’s older brother Dane was killed in a riding accident, after which Milutin moved the family to Gospić. Tesla attended the Real Gymnasium (junior high school) until 1870 and went to the Higher Real Gymnasium in Carlstadt, where he excelled in mathematics and became interested in electricity and magnetism.[6]

In 1875, Tesla received a scholarship to the Joanneum Polytechnic School (now the Graz University of Technology), where he studied engineering and electricity.[7] Tesla became disheartened by his father’s criticism and dropped out of school, although he later continued his education at the University of Prague.[8]

In 1881, Tesla moved to Budapest, Hungary, where he did electrical work. In the fall of 1882, Tesla moved to Paris and began working for the Continental Edison Company, where he tried unsuccessfully to interest Edison’s engineers in adopting his new AC motor design.[9]

Tesla, now twenty-eight years old, was invited by Charles Batchelor (1845–1910), one of Edison’s advisors, to travel to New York City and meet Edison in person.[10] Tesla was encouraged to make the move by Tivadar Puskás (1844–1893), an Edison associate, who sent a letter of introduction to Edison.[11]

Tesla arrived in New York City in June 1884 and met with Edison the day after his arrival. Edison hired Tesla that afternoon, but their working relationship was short-lived: the two men were very different from one another, Tesla worldly and reserved, Edison blunt and straightforward.[12] Tesla worked at the Edison Machine Works in Manhattan for six months, but Edison’s personality soon rubbed him raw, and after a disagreement over money, Tesla left the company. With the help of several investors, he established the Tesla Light and Manufacturing Company in 1886.[13]

Despite the hard work that Tesla put into the company, he showed a lack of business acumen by allowing the company to take control of his patents; he received only a stock certificate and was soon pushed out of the company.[14] Almost broke, he did menial work for a year, and then after meeting Alfred Brown, the director of Western Union, and Charles Peck, a New York City attorney, he formed the Tesla Electric Company, which launched in 1887. This time, Tesla was contracted to receive a third of the company’s profits.[15]

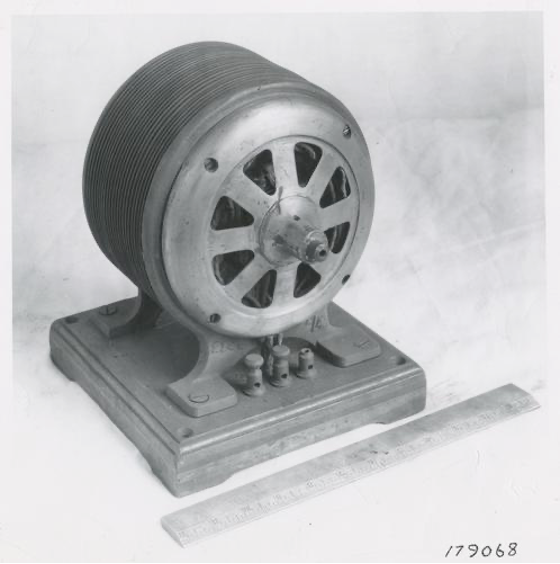

With a reliable paycheck and a laboratory to work in, Tesla turned his mind to inventing. He worked on improvements to direct-current (DC) motors and other projects, but his true interest lay in continuing the development of his AC induction motor. Tesla began working on a motor that utilized a rotating magnetic field to produce an alternating current. This new motor did not use a commutator, which is a rotary electrical switch that reverses the direction of electrical current. Because commutators have physical contacts they quickly wear down, but Tesla’s induction motor used a rotating magnetic field to provide torque.[16]

Within months, Tesla applied for seven patents, including one for his two-phase AC induction motor, and in May 1888 he was awarded a patent for the “Electro Magnetic Motor.” On May 16, 1888, Tesla presented his research paper, “A New System of Alternate-Current Motors and Transformers,” at a meeting of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers. Tesla’s work was well received at the meeting, and the major engineering trade journals reprinted his work. Investors soon became interested, and in July 1888 George Westinghouse signed an agreement with Tesla for the use of several polyphase patents in exchange for shares of stock and royalty payments. Westinghouse also hired Tesla to move to Pittsburg and oversee construction of an AC system.[17]

Tesla’s new polyphase motor was a significant acquisition because it allowed Westinghouse to compete with Edison’s DC system; it was simpler and easier to maintain than Elihu Thomson’s (1853–1937) competing AC motor and was thus more affordable.[18] The polyphase motor was able to handle high voltages and heavy loads, making it ideal for industrial applications.[19] Tesla also patented several modifications to his motor, including a variable speed option, that remain in use today.[20]

During the 1880s, electrical pioneers were competing to distribute electricity on a national level. Some, including Edison, pushed for a DC power distribution system, while others, including William Stanley (1858–1916), George Westinghouse, and Tesla, believed that AC was more efficient. Because existing AC power systems, which were used primarily for arc lighting in cities, had already caused several deaths from high-voltage lines sparking,[21] there was aversion to using it, and the differing opinions on which power system was best eventually turned into a bitter rivalry known as the “War of the Currents.”[22]

In 1893, Westinghouse won the contract to electrify the Columbia Exposition in Chicago. It was the first world’s fair to be lit by electricity, and was powered by Tesla’s polyphase AC electrical system. The Electricity Pavilion showcased new electrical inventions, and Tesla had a personal exhibit in part of the Westinghouse space. On display were several of Tesla’s alternating motors, some high-frequency apparatus, and an array of phosphorescent bulbs and tubes.[23]

After the success at the World’s Fair, Westinghouse was invited to bid on a hydroelectric project at Niagara Falls. The Westinghouse Company published a book in which it described its alternating current system and noted that the polyphase systems was the “original discovery of Mr. Tesla.”[24] Two large generators, based on Tesla’s design, went online November 16, 1896.[25]

In early 1895, Tesla established the Nikola Tesla Company with investor Edward Dean Adams, with the aim of manufacturing and selling electrical equipment, but on March 13 a fire gutted the laboratory and destroyed all of Tesla’s notes and equipment.[26] Devastated, Tesla nonetheless rebuilt his workshop. Intrigued by the work of Wilhem Röentgen (1845–1923), for a while Tesla dabbled in X-ray research but soon returned to working on wireless communications, which he demonstrated in 1898 using a remote-controlled boat at an electrical exposition at Madison Square Garden in New York.[27]

During the 1890s, Tesla began experimenting with wireless power and high voltage generators. In 1891, the same year he became a U.S. citizen, he patented an oscillating transformer capable of producing an electrical current that changed 30,000 times a second. This transformer became popularly known as the “Tesla coil,” arguably his most well-known invention.[28]

In 1899, Tesla moved to Colorado Springs, where he spent eight months experimenting with wireless power transmission. He constructed a laboratory with a retractable roof and installed a large copper ball at the top of a 142-foot metal tower, which in turn was mounted to an 80-foot tower on the roof of the laboratory. Tesla believed that the Earth behaved as a massive conductor, and that by sending signals into the planet he could deliver free electricity without the use of wires. He also mistakenly believed that this would be a lossless system; however, electromagnetic fields weaken over distances, which makes a true lossless system impossible.

Tesla’s experiments pulled huge amounts of power from the local electrical company. When he performed one of his experiments, large sparks of man-made lightning flew off the mast and overloaded the El Paso Electric Company’s generating plant, bringing down the entire city’s power system.[29] Despite his lofty humanitarian goal of providing free energy to the world, Tesla again showed that he did not understand business: it did not occur to him that the El Paso company had to buy fuel to generate power and pay its employees for their labor, which meant they needed to charge for their energy generation.

Tesla also detected a weak oscillating signal that he believed came from outer space. Although Tesla initially kept the information to himself, he eventually told a reporter about the discovery. Tesla did not believe that the signals could be natural emanations from the sun or Earth, and he gushed about the possibility of a message from another world; almost immediately he was ridiculed in the press for speaking to Martians.[30]

Returning to New York in January 1900, Tesla had ambitions to build a large transmission tower that he hoped would produce a handsome profit. Buoyed by the possibilities, he moved into the fashionable Waldorf Astoria hotel.[31] That year, he wrote an article for Century Magazine in which he prophesied a future with wireless communications and a host of other fantastic-sounding schemes. Most thought his predictions to be hyperbole, but Morgan offered Tesla $150,000 to build his power plant.[32]

Tesla bought land along Long Island Sound and hired the architect Stanford White (1853–1906) to design a laboratory.[33] Construction began in November 1901. Tesla had originally calculated his transmission tower’s height at 600 feet, but rapidly rising costs, partially due to Tesla’s penchant toward the grandiose, forced him to reduce his expectations. He settled on a design for a 187-foot tower topped by a 68-foot dome, which resembled a mushroom with a long stalk.[34] The Wardenclyffe Tower project continually needed more cash, but unable to convince Morgan—or any other financier—to invest more funds into it, Tesla struggled along for a few years and reluctantly abandoned the project in 1905.[35]

After the failure of Wardenclyffe, Tesla suffered from a nervous breakdown.[36] The inventor was short of money and he spent several years working as a consultant. After designing a successful bladeless turbine engine in 1912, he was unable to build a successful working model because the materials available to him at the time used were unable to take the strain.[37] Tesla’s financial condition continued to worsen, and in 1917 the Waldorf evicted him for unpaid bills.[38] Tesla grew increasingly isolated after the death of several friends and relatives.

In 1917, Tesla was awarded the seventh annual Edison Medal from the American Institute of Electrical Engineers for “early original work in polyphase and high-frequency electric currents.”[39] The award ceremony was scheduled for May 18, but midway through the event Tesla disappeared and was found sitting on a park bench covered in pigeons.[40] His fascination with these birds eventually morphed into a “delusional obsession” and Tesla began taking injured birds back to his hotel room to nurse them back to health.[41]

After World War I, when it seemed likely that another war would break out in Europe, Tesla began working on an energy source that he claimed would make warfare obsolete. He wrote a paper called “The New Art of Projecting Concentrated Non-dispersive Energy through Natural Media” and canvassed several countries for support. Tesla’s device was essentially a charged particle beam weapon, and the only country interested was the Soviet Union, which paid Tesla $25,000 for the idea.[42] Another of Tesla’s ideas was a vertical takeoff-and-landing vehicle, for which he filed and received a patent in 1928.[43]

One August evening in 1937, the 81-year-old Tesla was hit by a taxi and suffered three broken ribs. He was bedridden and refused both medical care and visitors. Tesla’s health began to decline, and on January 7, 1943, he died in his sleep.[44]

His death soon sparked controversy. Tesla’s nephew Sava Kosanovic, administrator of his estate, went to Tesla’s hotel room shortly after his death. Kosanovic claimed that several of Tesla’s technical papers were missing, as well as a black notebook.[45] Tesla had claimed to have perfected his “death beam,” which led to the FBI becoming “vitally interested” in his papers, but because Kosanovic was not an American citizen the case was turned over to the Alien Property Custodian Office, which spent weeks attempting to locate all of Telsa’s papers and ended up with more than sixty containers of materials.[46]The FBI asserted that it never had any of Tesla’s papers in its possession, yet in 2016 the agency declassified 250 pages of documents related to Tesla.[47] Additional documents remain missing, and what happened to them remains a mystery.

Tesla’s preferred method of inventing was to work alone, rather than as part of a team.[48] He is credited with having created the modern electrical world, but without his close association with the Westinghouse company, his work on alternating current may never have made it out of the laboratory. Despite his foibles and quirks, Tesla’s legacy of engineering lives on in the electrical grid, AC motors, and communications systems that we use every day.

Although, in the end, Tesla ended up being part of a team, he just might have been the most valuable player.

Further Reading:

Bolotin, Norman, and Christine Laing. The World’s Columbian Exposition: The Chicago World’s Fair of 1893. Champaign, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2002.

Carlson, W. Bernard. Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013.

Christopher Newport University, “Primary Sources: Energy: Tesla, Nikola,” https://cnu.libguides.com/psenergy/nikolatesla (accessed August 15, 2019).

Cooper, Christopher. The Truth about Tesla: The Myth of the Lone Genius in the History of Innovation. New York: Quarto, 2015.

Federal Bureau of Investigation, FBI Records: The Vault, “Nikola Tesla,” https://vault.fbi.gov/nikola-tesla (accessed August 15, 2019).

Garvin, Karen S. “Electricity, War of the Currents,” in Technical Innovation in American History vol. 2, ed. Rosanne Welch and Peg A. Lamphier. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2019, 61–63.

Jonnes, Jill. Empires of Light: Edison, Tesla, Westinghouse, and the Race to Electrify the World. New York: Random House, 2004.

Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, “The Invention of the Electric Motor 1856–1893,” https://www.eti.kit.edu/english/1390.php (accessed August 15, 2019).

Martin, Thomas Commerford. The Inventions Researches and Writings of Nikola Tesla. New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1894.

Munson, Richard. Tesla: Inventor of the Modern. New York: W.W. Norton, 2018.

“Nikola Tesla Becomes the Recipient of Edison Medal,” May 19, 1917, Electrical World 69, no. 20, 980–81, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/electricalworld69newy/page/980 (accessed May 16, 2019).

PBS, “Colorado Springs,” Tesla Life and Legacy, https://www.pbs.org/tesla/ll/ll_colspr.html (accessed August 7, 2020).

PBS, “The Missing Papers,” Tesla Life and Legacy, https://www.pbs.org/tesla/ll/ll_mispapers.html (accessed August 15, 2019).

PBS, “Tesla: Master of Lightning,” https://www.pbs.org/tesla/index.html (accessed May 9, 2019).

PBS, “Race of Robots,” Tesla Life and Legacy, https://www.pbs.org/tesla/ll/ll_robots.html (accessed August 15, 2019).

Rutgers School of Arts and Sciences, Thomas A. Edison Papers Project, http://edison.rutgers.edu/.

Schiffer, Michael Brian. Power Struggles: Scientific Authority and the Creation of Practical Electricity before Edison. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008.

Tesla, Nikola. My Inventions: The Autobiography of Nikola Tesla. New York: Experimenter Publishing, 1919.

Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company, Transmission of Power: Polyphase System, Tesla Patents (Pittsburg: Westinghouse, 1893).

[1]. Richard Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern (New York: W.W. Norton, 2018), 1.

[2]. Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 6–7.

[3]. Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 173–74.

[4]. Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 223–24.

[5]. Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 9, 11, 15.

[6]. Carlson, Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age, 21–22, 26–28.

[7]. Carlson, Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age, 34; Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 23, 27.

[8]. Carlson, Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age, 47; Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 29.

[9]. PBS, “Coming to America,” Tesla Life and Legacy, https://www.pbs.org/tesla/ll/ll_america.html (accessed May 5, 2019); Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 43.

[10]. Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 45.

[11]. Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 46.

[12]. Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 48, 52–53.

[13]. Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 54.

[14]. Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 54–55.

[15]. Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 56.

[16]. Karen S. Garvin, “AC Induction Motor,” in Technical Innovation in American History vol. 2, ed. Rosanne Welch and Peg A. Lamphier (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2019), 10–11.

[17]. Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 61–65; Tesla Universe, “Tesla’s Speech Before AIEE,” https://teslauniverse.com/nikola-tesla/timeline/1856-birth-nikola-tesla#goto-281 (accessed August 15, 2019).

[18]. All about Circuits, “Tesla Polyphase Induction Motors,” EETech Media, https://www.allaboutcircuits.com/textbook/alternating-current/chpt-13/tesla-polyphase-induction-motors/ (accessed May 10, 2019).

[19]. Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 63.

[20]. PBS, “Anatomy of a Motor,” Inside the Lab, https://www.pbs.org/tesla/ins/lab_acmotor.html (accessed August 15, 2019).

[21]. Ernest Freeburg, The Age of Edison: Electric Light and the Invention of Modern America (New York: Penguin Books, 2013), 80–84.

[22]. Karen S. Garvin, “Electricity, War of the Currents,” in Technical Innovation in American History vol. 2, ed. Rosanne Welch and Peg A. Lamphier (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2019), 61–63; Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 91–101.

[23]. Thomas Commerford Martin, The Inventions Researches and Writings of Nikola Tesla (New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1894), 477–85; Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 105–110.

[24]. Transmission of Power: Polyphase System, Tesla Patents (Pittsburg: Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company, 1893), iv.

[25]. Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 113.

[26]. Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 136–39.

[27]. PBS, “Race of Robots,” Tesla Life and Legacy, https://www.pbs.org/tesla/ll/ll_robots.html (accessed August 15, 2019).

[28]. Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 74.

[29]. PBS, “Colorado Springs,” Tesla Life and Legacy, https://www.pbs.org/tesla/ll/ll_colspr.html (accessed August 7, 2020); Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 163–64.

[30]. Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 163–64.

[31]. Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 167.

[32]. PBS, “Tower of Dreams,” Tesla Life and Legacy, https://www.pbs.org/tesla/ll/ll_todre.html (accessed August 15, 2019); Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 167, 173.

[33]. Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 175.

[34]. Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 177–78; PBS, “Tesla’s Tower with Dome Frame, Completed in 1904,” Tesla Life and Legacy, https://www.pbs.org/tesla/ll/td_tow2_pop.html.

[35]. PBS, “Tower of Dreams.”

[36]. PBS,” Tower of Dreams.”

[37]. PBS, “Poet and Visionary,” Tesla Life and Legacy, https://www.pbs.org/tesla/ll/ll_poevis.html; Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 193, 196–198.

[38]. Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 216.

[39]. “Nikola Tesla Becomes the Recipient of Edison Medal,” Electrical World 69, no. 20, 980–81, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/electricalworld69newy/page/980 (accessed May 16, 2019).

[40]. Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 209.

[41]. Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 217.

[42]. PBS, “A Weapon to End War,” Tesla Life and Legacy, https://www.pbs.org/tesla/ll/ll_wendwar.html (accessed may 17, 1029); Nikola Tesla, “The New Art of Projecting Concentrated Non-dispersive Energy through Natural Media,” Inventions and Experiments of Nikola Tesla, https://teslaresearch.jimdo.com/death-ray/the-new-art-of-projecting-concentrated-non-dispersive-energy-through-natural-media-briefly-exposed-by-nikola-tesla-circa-may-16-1935/ (accessed May 17, 2019); Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 230.

[43]. Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 198–99.

[44]. Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 232–33.

[45]. Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 239; PBS, “The Missing Papers,” Tesla Life and Legacy, https://www.pbs.org/tesla/ll/ll_mispapers.html (accessed August 15, 2019).

[46]. PBS, “The Missing Papers”; Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 238–40.

[47]. Sarah Pruitt, “The Mystery of Nikola Tesla’s Missing Files,” May 3, 2018, History, A&E Television Networks, https://www.history.com/news/nikola-tesla-files-declassified-fbi (accessed May 17, 2019).

[48]. Munson, Tesla: Inventor of the Modern, 244.