Hodan Osman

NOTE: This sidebar was added for fall 2018, and is not yet reflected in the print edition.

China is like a sleeping giant. And when she awakes, she shall astonish the world.

–Napoleon Bonaparte, 1803

By most accounts, China is considered one of the most entrepreneurial countries worldwide. As the second largest economy in the world, it is also home to 53 percent of the world’s unicorns, a term coined by venture capitalist Aileen Lee in 2013 that refers to startups valued at $1 billion USD or more.[1] The combination of 108 Chinese unicorns in 2017 had a combined worth of more than $445 billion USD, a figure equivalent to the GDP of the world’s 26th largest economy.[2] Many of these rising unicorns are media and technology startups that are positioned to capitalize on the technological, socio-cultural, and socio-economic changes in the country. A report published in 2017 by Chinese startup database IT Juzi indicated that there were 34 new Chinese companies that year alone, with media companies such as Kuaishou, Kuaikan Manhua “Quick Comic,” and Luoji Siwei “Logical Thinking” dominating the list.[3]

The rapid economic developments in China in recent years have fostered technological innovations that have allowed for a new wave of media entrepreneurship to emerge. While some represent efforts by the state to appeal to the younger generations by funding and endorsing new media outlets, most are business ventures created by media professionals or individual entrepreneurs hoping to reach unicorn scale by succeeding within the Chinese markets that cater to 850 million people under the age of 40.[4] The high penetration rate of mobile phones and the Internet in China make it easy for startups to reach vast markets cheaply by tapping into the market of 731 million Internet users, and 695 million mobile phone users in the country.[5] Tencent, Baidu, WeChat, Youku, Weibo and Toutiao are all examples of explosive media enterprises that have witnessed tremendous growth in China in recent years. These platforms gained popularity with Chinese netizens, a term widely used to refer to Chinese Internet users, not only for giving them a platform to share and access information, but also for enabling users to make money as well. These platforms allowed their users to become their own entrepreneurs through multiple innovative methods.

This trend began with the rise of zi meiti or “self-media” in China, such as Tencent blogging in the early 2000s, followed by the later formation of Weibo, the Twitter-like social media app in 2010, and the launching of WeChat in 2011. While blogging spaces and Weibo accounts became important outlets for civic engagement and political participation, the use of platforms such as WeChat opened up the possibilities for users to make a significant financial income, turning their media participation activities into profitable entrepreneurial ventures.

WeChat, which is currently the most popular messaging app in China, has a platform ecosystem of over 200,000 developers and offers an ever-expanding range of services such as chat, voice and video calls, social media, news, payments, hotel booking, and so on to its almost 1 billion monthly active users.

| Communication | Social Network | Value-Added Services |

|

|

|

Illustration of WeChat app functions, screenshot images provided by author.

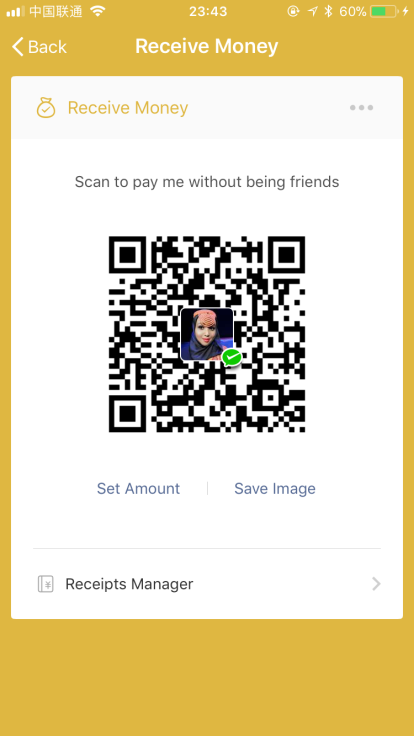

WeChat was developed by Tencent Holdings, Asia’s most valuable listed company with a market capitalization of nearly $500 billion USD on the Nikkei Asian stock exchange at the end of 2017.[6] Tencent, China’s largest social network and gaming firm, rolled out WeChat in 2011 as a mobile-only messaging app that would disrupt SMS messaging and work on any phone and any mobile service. It first had only basic capabilities such as text messaging, creating voice clips, and sending photos. Later on, it added features such as video clips and a “find nearby users” function. The app quickly gained popularity and reached 100 million users in less than 14 months after launching, tripling that number the following year to reach 300 million users in 2013. In 2012, the app added voice and video call services, and opened up to national and international commercial brands by introducing public accounts users could follow by simply scanning a personalized QR code. Soon after that, the app introduced more value-added features including games, mobile payments, WeChat stores, and Mini programs. The app now has more than 1 billion active monthly users, and is currently rolling out its services worldwide in a plan to expand globally.

China is considered a mobile-first market, since the vast majority of its consumers joined the Internet on a mobile device before a computer, an important factor that contributed to the popularity of chat apps such as WeChat. However, one of WeChat’s key elements of success was its deep understanding of Chinese digital culture, which carries unique societal norms into the digital space. For example, the platform introduced Hong Bao or “Red Envelopes” — a traditional form of cash gifts in red envelopes culturally considered auspicious — in a digital format as a form of payment between users within the app instead of normal transfers. Combining the traditional Hong Bao with digital instant money transfers became one of the innovative approaches that gained popularity in the country.

With the convenience of online payment portals in China, and the rising number of WeChat users, social networks became important e-commerce hubs. In 2016, Chinese consumers spent $31.3 billion USD on digital content purchases, including novels, audio, and videos, a 28 percent jump compared to the same period in 2015.[7] To capitalize on the trend of social commerce, facilitating online shopping with the use of user ratings, referrals, online communities, and social advertising on online social networks, WeChat began to open up its platform for developers to build e-commerce stores as early as 2014. By 2016, 31 percent of WeChat users were making e-commerce purchases on the platform according to a report published by Silicon Valley venture capitalist Mary Meeker.[8] Some startup companies embedded entire e-commerce platforms inside WeChat. WeChat Stores or “Wei Dian,” an interface akin to Shopify that connects to the menu of WeChat public accounts and allows one-click-payments for WeChat users, became one of its most popular and convenient e-commerce platforms.

WeChat Stores allowed for users to build well-designed stores for free in a simple-to-follow process that took less than 10 minutes to complete. And while it didn’t allow for product searches like traditional e-commerce sites, it had a successful marketing strategy of linking users from your public WeChat account to your WeChat store. As such, WeChat’s public accounts became important incubators for emerging entrepreneurs and startups that began by featuring innovative media products and services on the platform and offering deals and coupons for group purchases to drive traffic to their stores. For example, Luoji Siwei, or “Logical Thinking,” an online talk show anchored by its founder Luo Zhenyu, started out as a WeChat public account and successfully capitalized on its model. Eventually it secured investment from venture capitalists and completed Series B financing in October 2015, when it was valued at more than $460 million USD,[9] making it one of the most valuable WeChat-born unicorns.

Since WeChat’s launch, media entrepreneurs in China largely used WeChat as a platform for their businesses instead of developing their own apps or websites. Startups such as Luoji Siwei conducted innovative content marketing by offering creative products, introduced by stories, in a limited quantity and time. It offered a daily 60-second audio from the host at 6:30 am every day, in which he shared interesting perspectives on common issues such as parenting. His WeChat store sold books and other products he mentioned in these talks to 3.5 million followers, and 30,000 paid members. Occasionally, Luoji Siwei launched very successful e-commerce campaigns, such as the Mooncake campaign in which 2.7 million people participated in a game that involved buying and receiving Mooncakes, popular festive delicacies shared as gifts. Later on, Luoji Siwei continued to expand his business offline by offering talks and seminars in popular cities with ticket prices as high as $2,200 USD as fans rushed to attend these activities.

Another example of media entrepreneurship within WeChat is Uncle Tongdao, a brand that was founded by Cai Yuedong, a 28-year-old illustrator on WeChat. His Uncle Astrology cartoon series about the 12 astrology zodiac signs became an instantaneous hit as they combined the Chinese culture of Tucao or “sarcastically complaining” with the hip culture of astrology. Its success depended on WeChat’s integrated ecosystem that allowed for multiple online and offline revenue streams including advertising, creating customized products, emojis, WeChat shops, and creating an offline presence such as setting up the Uncle Tongdao Cafe and Store in Shanghai, and organizing the astrology gala in Guangzhou where they sold products worth 2 million RMB (approx $317,000 USD at time of writing). On December 2016, Cai Yuedong went from freelance illustrator to millionaire after he sold 73 percent of his startup Tongdao Culture Studio to Shanghai-listed media company Meisheng for $25 million USD.

When Tencent first launched WeChat in 2011, no one predicted that the mobile-only messenger app designed to reinvent SMS messaging would in less than five years grow to become one of the world’s largest e-commerce and social media platforms. In China, WeChat eclipses many of the country’s former social media giants such as Renren and Weibo, and within minutes of meeting someone new in China, it is very likely that you will connect on the popular app. Today, teachers communicate with parents through WeChat groups, and some companies even make important staff announcements on their public accounts, making the app an essential part of professional and social life in China. On the other hand, WeChat not only provides space to stay connected with people, it also offers essential services such as news and shopping. Today, we find a WeChat payment QR code stuck to counters everywhere in the country as the app increasingly becomes a popular payment method in transactions from buying coffee to paying utility fees. The app also continues to provide entrepreneurs with innovative new ways of reaching customers and selling their products and services, such as WeChat’s latest Mini Programs–lightweight apps embedded within WeChat that don’t need to be installed, and offer a range of services from hailing rides and food delivery to live-streaming, and coupons for group purchases. Since Mini Programs were launched in 2017, developers introduced more than 580,000 Mini Programs aimed at capitalizing on the large potential of social commerce on WeChat’s network of 1 billion users.

Factors for successful WeChat entrepreneurship

Analysis of the above-mentioned examples shows that the success of media entrepreneurship attempts on WeChat depends on the capitalization of the following factors:

- Monetization through multiple channels – WeChat offers a complex environment that combines social content with e-commerce, and allows for user engagement both online through social media content and offline through QR code scanning.

- Designing unique products – by designing their own unique products, entrepreneurs on WeChat were able to align their content with products and further enhance user experience and entice user interaction.

- Ensuring an offline presence alongside the online presence – keeping an offline presence through physical shops or events allows for a better user experience and a more strategic immersion into the daily interactions of users.

- Grounding a brand and product within the popular culture – the digitization of the red-envelope cash-gifts culture by WeChat, and how Uncle Tongdao playfully allowed for the culture of Tucao “sarcastically complaining” to combine with astrology zodiac signs, are both examples of media and digital innovations that are grounded within popular culture.

- Commitment to your original voice – in order to ensure long-term user engagement, staying true to your brand and original voice is key in ensuring user loyalty.

Hodan Osman is the executive director of the Center for East African Studies, vice director of The Center for African Film and TV Research, and a research fellow & lecturer at The Institute of African Studies at Zhejiang Normal University. Find her on Twitter at @DrHodanOsman.

- “It’s the Age of Unicorns and Here’s How China is Ranking,” World Economic Forum, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/07/its-the-age-of-unicorns-and-heres-how-china-is-ranking. ↵

- “It’s the Age of Unicorns and Here’s How China is Ranking,” World Economic Forum, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/07/its-the-age-of-unicorns-and-heres-how-china-is-ranking. ↵

- “4 Takeaways from 34 New Chinese Unicorns: It Juzi Report,” TechNode, https://technode.com/2018/01/04/itjuzi-chinese-unicorns/. ↵

- “China Population,” World Population Review, http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/china-population/. ↵

- The 39th statistical report on the development of the internet in China, China Internet Network Information Center, 2017. ↵

- "Tencent and Alibaba Top Asia's Market Cap Ranking in 2017," Nikkei Asian Review, https://asia.nikkei.com/magazine/20180111/Business/Tencent-and-Alibaba-top-Asia-s-market-cap-ranking-in-2017. ↵

- "Internet Players Cash in on Content Windfall," China Daily USA, http://usa.chinadaily.com.cn/epaper/2017-08/03/content_30344557.htm. ↵

- “2018 Internet Trends,” Kleiner, Perkins, Caufield, Byers, https://www.kleinerperkins.com/perspectives/internet-trends-report-2018/. ↵

- Eds Picker Colin, Wang Heng & Zhou Weihuan. The China-Australia Free Trade Agreement: A 21st-Century Model. (Oxford, England: Hart Publishing, 2018). ↵