Geoffrey Graybeal

Dive In

A business model helps to clarify a company’s main purpose, such as who they’re serving, how they help, and how the company can sustain its operations. A business model is distinctly different from an organization’s strategy, which typically addresses product, pricing, and marketing decisions. A formal business plan, however, may include some of these elements as part of the company’s long-term goals and objectives.

Defining Key Terms

| Business Model | Business Plan | Revenue Model |

|---|---|---|

| A business model provides a rationale for how a business creates, delivers and captures value, and examines how the business operates, its underlying foundations, and the exchange activities and financial flows upon which it can be successful. | A business plan is a formal document that typically describes the business and industry, market strategies, sales potential, and competitive analysis as well as the company's long-term goals and objectives. | A revenue model outlines the ways in which your company will make money (e.g. revenue streams). |

Each business model is unique to a company. There is not an industry-wide business model per se although companies may coalesce around a dominant company’s successful business model and seek to emulate it.

Business models provide a rationale for how a business creates, delivers, and captures value,[1] and examine how the business operates, its underlying foundations, and the exchange activities and financial flows upon which it can be successful.[2]

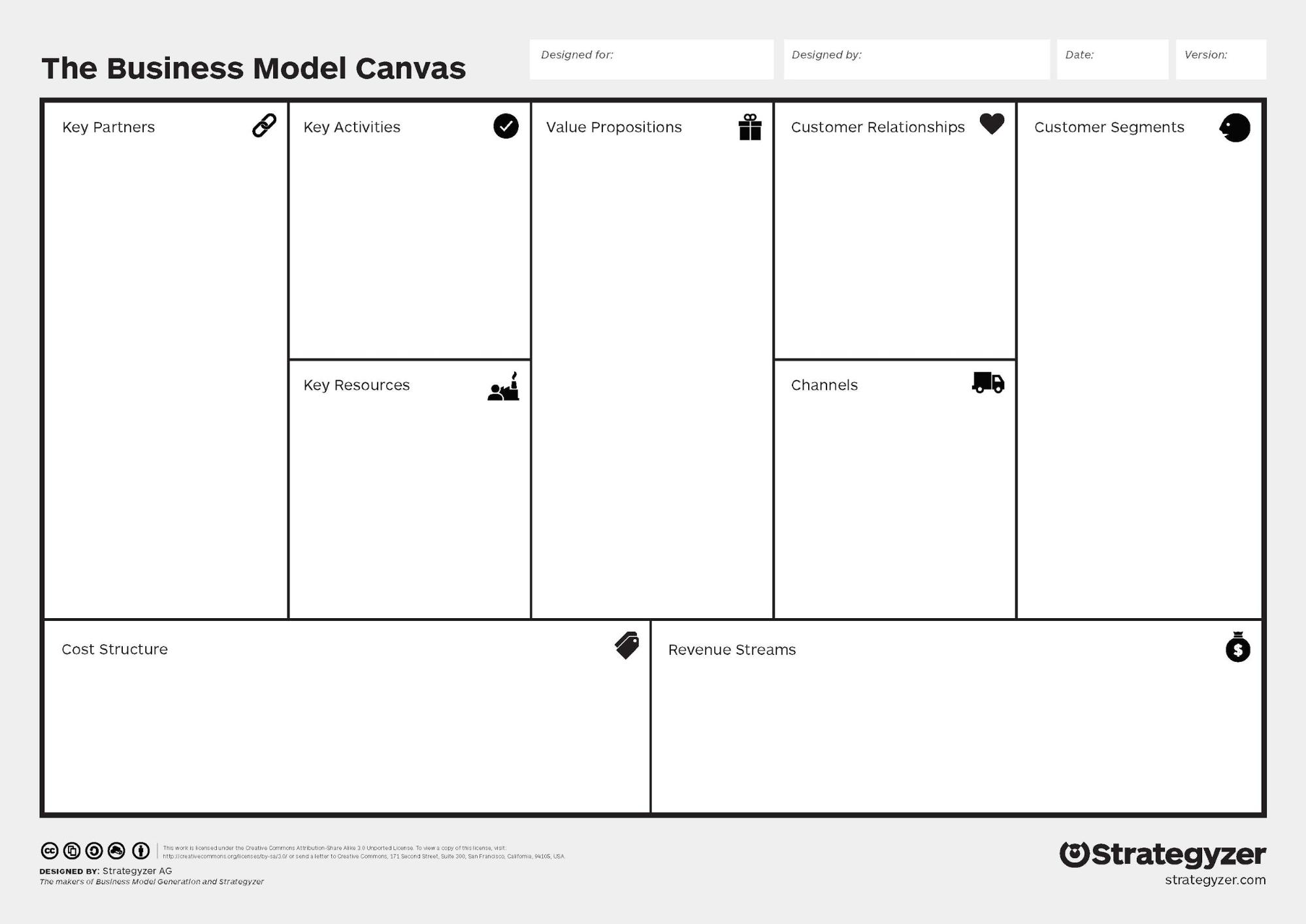

A business model canvas is a tool to map out and plan the different components to a business model. The components vary based on the canvas tool you use, with the most widely used one developed by Osterwalder and Pigneur in the book Business Model Generation, or available online through a series of customizable tools and canvases available for a fee on strategyzer.com.

The Osterwalder and Pigneur canvas blocks[3] include revenue stream, customer segments, value proposition, cost structures, channels, key activities, key partners, key resources, and customer relationships.

Early on, your greatest focus should be on the right side of the canvas because:

- These are in many ways the most critical aspects of starting a new venture (customer segments, value proposition, channels, and revenue streams).

- The most fluid (revenue streams, channels, and value propositions will likely differ for the differing customer segments and as you iterate and pivot throughout the customer discovery process could change).

- It follows a logical temporal order (there’s no need to focus on the costs of building a company if you won’t have customers).

In a follow up to Business Model Generation, the Strategyzer team created a second canvas, the Value Proposition Canvas. Value Proposition Canvas[4] is a new tool that pulls out the customer segment and value proposition blocks of the business model canvas and encourages more in-depth exploration of those blocks to achieve “fit” between the two. The Value Proposition Canvas tool looks at customer pains, gains and jobs-to-be-done on the customer side and painkillers, gain creators, and products and services on the value proposition side.

A revenue model focuses on an organization’s revenue streams, e.g., how a company will make money, whereas a business model also concerns itself with other issues such as who the product is serving, how it is distributed and promoted, and key partnerships used in implementing it. In short, a revenue model is just one component of a business model. A typical business model has multiple elements (nine in the case of the Osterwalder and Pigneur model). A revenue model is primarily focused on how a company will make money.

For traditional legacy media outlets, such as a newspaper, revenue streams typically encompassed advertising and consumer payment either through subscription or alternate payment methods like single-sale purchases.

Hayes and Graybeal (2012) provide an overview of categorizations of online business models from the late 1990s to late 2000s from scholars and industry practitioners, including many online content plays. Revenue models were the most common components found in all forms of business model classifications. Value streams and logistical streams were also equally important in e-commerce models.[5]

Think of a business model canvas as an ideation tool to help brainstorm and flesh out your startup concept. The business model is a more adaptable, flexible tool that can be used to formulate the ideas that would later be fleshed out in a more formal business plan.

A business plan is a formal document, presented to prospective investors, that typically includes elements such as an executive summary, business description, marketing strategy, and competitive analysis. A business plan may also include a business model canvas as supplemental material in an appendix.

You should usually develop a business model before a business plan. But before you get to a business model, first and foremost, you need an idea. There are numerous resources for brainstorming activities and entrepreneurial processes to help develop an idea and flesh it out to be “market-ready.” (see previous chapter on Ideation[6]) Original ideas are sometimes hard to come by.

Early research into competitors helps as a starting point. Who else has had this idea? Has this idea been tried before and failed? That’s not necessarily a dealbreaker. As renowned media economist Robert Picard notes, just because an idea failed at one point in time, under a certain set of circumstances, that doesn’t mean a failed idea can’t be revisited.[7]

Another entrepreneurial startup truism is that no matter how great your idea may be, if no one will use your product, then you’re dead on arrival. So startup ideas need customers to become a business. Thus, the various entrepreneurial processes, whether that is business model canvas tools, lean startup principles and methodologies, or other approaches, focus a great deal on the customer.

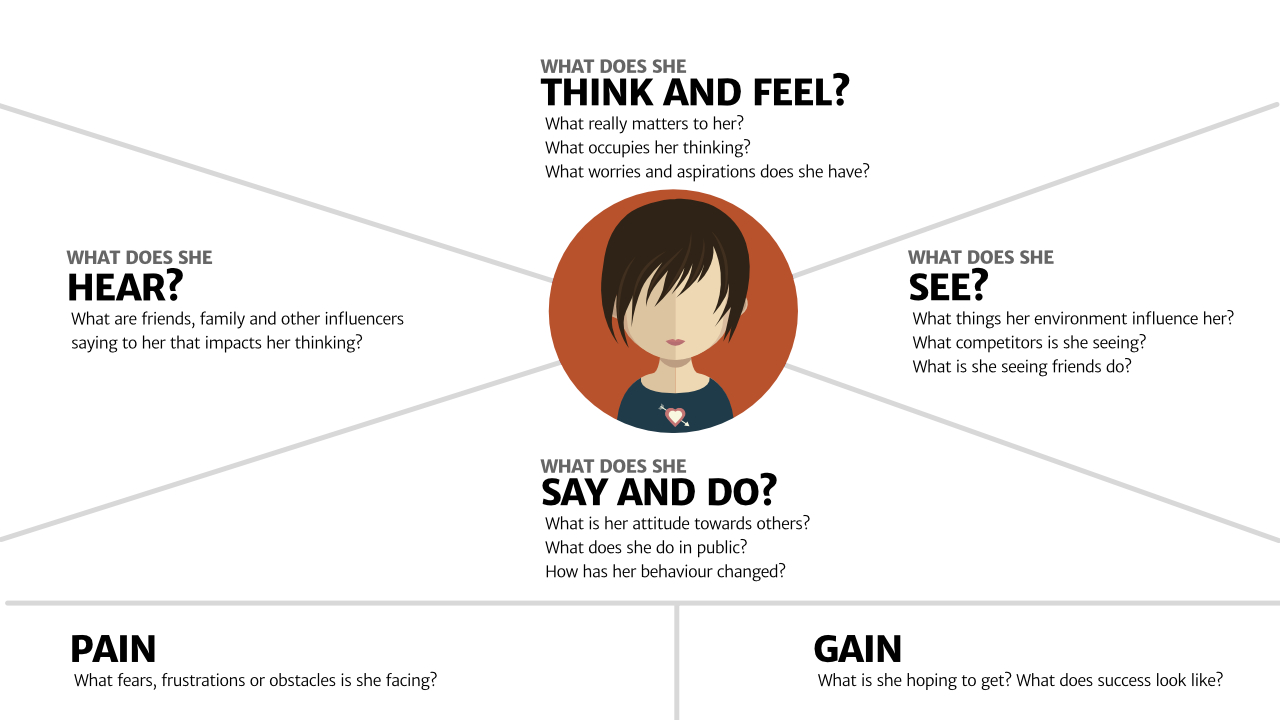

The Osterwalder and Pigneur book describes a process of creating a customer empathy map to distill down your ideal target customer. Bring to life an individual, and delve into his or her fears, dreams, aspirations, and what she or he does in the everyday life. After identifying your target customer, you can begin to segment your audience. But start with an individual customer, idealized or actualized, and distill deeply into that customer profile.[8]

The Customer Empathy Map is an idealized portrayal of your fictionalized target customer, the most promising candidate from your customer segments. Give him or her a name and demographic characteristics, such as income, marital status, and so forth, before delving into the pains, gains, thoughts, feelings, and surroundings of this individual you bring to fruition.

This is an approach that has long been used in media and communication fields such as advertising and strategic communication. Advertisers and marketers often create customer personas–fictional, generalized representations of ideal or existing customers–as part of campaign plans, pitches, strategy, and creative concept delivery.

When you peel away the language used to describe business models, the early startup planning stages come down to asking a series of questions. Another popular framework used in entrepreneurial circles when it comes to formulating a business model for a startup concept is that of desirability-feasibility-viability.

This forces the entrepreneur to address broad questions about the startup concept.

Desirability: How desirable is the product? Who will use it and why?

Feasibility: How feasible is this idea? What are the costs to make it? How practical is the concept?

Viability: Will this idea remain viable? How will it make money? How will it be sustained over time?

These questions then begin to connect together to form a narrative about where the startup concept came from, who it serves, why it’s needed, how it will make money, and how it will be sustained in the future.

Strategyzer also has a great “Ad-lib” template[9] that will help you figure out a few potential value propositions. They also offer other resources[10] you can access after signing up for a free account.

Business Models

Although there is not a single definition to the term business model and usage varies widely, in standard business usage a “business model” can denote how costs will be covered as well as how a business creates and delivers value for itself and its customers, including the ways in which products are made and distributed. Academic strategists tend to use the term business model to describe the configuration of resources in response to a particular strategic orientation.[11][12][13]

Most people are familiar with Business to Consumer models (also referred to as BTC or B2C). In a Business-to-Consumer model, the business primarily provides services to consumers. Many of the common media content plays are considered B2C. Newspapers, television shows, films, and video games are primarily B2C companies. Many apps that individual users download and then consume content from are B2C. Because media companies are typically providing content that is of value to consumers, they look like a B2C, however, they use the attention of those consumers to sell advertising space to businesses, effectively operating as a B2B. Business to business to consumer (or B2B2C or BtoBtoC) is another prominent e-commerce model, that combines Business to Business and Business to Consumer in a complete product or service transaction.

Nascent startup Shine, which officially launched its inspirational text message service in Spring 2016, is an example of following a classic Business-to-Consumer model. (Full disclosure: I taught one of the founders.) Through automated texts, Shine delivers daily self-help, encouragement and advice to its subscribers via either SMS or Facebook Messenger. Anyone can use the free service, but it is primarily aimed at millennials and about 70 percent of users are female.

On the Brooklyn-based company’s one-year anniversary in April 2017, the Shine team announced that it had obtained half a million users. Co-founders Marah Lidey and Naomi Hirabayashi raised $2.5 million to further develop Shine in a funding round led by Betaworks and Eniac Ventures, and including Female Founders Fund, Felix Capital, Comcast Venture, BBG Ventures, The New York Times, and Ed Zimmerman.

They want to expand the service to be included on other platforms like Line and WeChat.

The problem Shine tackles is that “self-help is broken” and its value proposition addresses in part what is known as “the confidence gap,” often cited as a barrier that holds women back when it comes to advancing in their careers, raising money, investing, and planning retirement.

Shine has four pillars it is built to address: mental health, confidence, daily happiness, and productivity.

In 2015, Hirayabashi and Lidey began to focus on turning their idea into a reality. The two met at and worked together at DoSomething.org, a youth-oriented global nonprofit organization. They conducted a closed test with 70 individuals before publicly releasing Shine in beta in October 2015. They formally left DoSomething.Org in April 2016 and Shine was born.

While the messaging service is free, the company has experimented with adding revenue streams through additional consumer services. Shinevisor provides advice and guidance from real people who are certified life, career, and school coaches. That service currently runs $15.99 per week billed on a 12-week basis. Shinevisor is an early effort of Shine to add additional services that bring in revenue, as multiple revenue streams are most often needed for a company to succeed.

While Shine, apps and a majority of content plays are primarily B2C, the other predominant business model is that of a Business to Business, also commonly referred to as B2B or BTB. Whereas Shine is a business whose product serves customers, in a Business to Business model, a company primarily serves other businesses, not individual consumers.

MailChimp, an Atlanta-based company, began as a B2B in 2001. More than 15 million people and businesses around the world use MailChimp. MailChimp enables many B2B marketing transactions. A leading marketing automation platform, MailChimp sends more than a billion emails a day. MailChimp’s primary customers were businesses that used the platform to send marketing emails, automated messages, and targeted campaigns to its individual users.

Historically, media companies that provide analytic services have sold that data and analysis to other businesses. Bloomberg’s financial terminals sold to businesses around the world is a classic example of a B2B service.

Küng, Picard & Towse (2008) also note “elements of different business models can be combined [so] in that sense, every business model of a company is unique.”[14] For those reasons, a business model can be a source of competitive advantage, with business model design and product-market strategy serving as complements, not substitutes.[15] Strategy functions like an architect creating a homeowner’s design, while the detailed floor plan based on choices in the design process would constitute a business model design.[16]

When you go to get funding for your startup (more on this in a later chapter),[17] having an understanding of your business model will come in handy.

Regulation

Media are among the handful of industries that face industry-specific policies and regulations that other businesses do not face. The broadcast industry is regulated in the U.S. through the Federal Communication Commission. The print media industry is impacted by certain postal and governmental notice regulations. Banking and pharmaceuticals are other industries that face such industry-specific regulations. Reduced barriers to entry, promotion of trade, promotion of small enterprises, and regulation of consolidation and concentration are among some of the policies and regulations media must face. Media strategy can be influenced by these environmental factors, firm factors, industry factors, and media-specific factors, among others.[18] Some regulation can hinder startups.

That’s why policy is one of the domains of enabling an entrepreneurial ecosystem. Government supports can come in the forms of tax breaks and incentives, regulatory frameworks, venture-friendly legislation, institutional investments, financial support, and policy initiatives.[19] Regulation and policy limitations to the strategic choices available to media companies are two examples of media-specific characteristics.

Regulation can help or hinder incumbents or startups based on policies that are set. For example, regulations pertaining to net neutrality have been debated for years, with many startups of the past decade arguing that without net neutrality they would have faced disadvantages instead of the environment that enabled them to grow and prosper. Many technology startups, for example, banded together in July 2017 to form a protest over FCC proposals to eliminate Obama-era net neutrality rules. Y Combinator, a popular technology startup incubator, was among the backers of the protest, along with companies like Kickstarter, Etsy, GitHub, Amazon, and Reddit.

Government policies can also support entrepreneurship. Some U.S. cities have staff dedicated to innovation and entrepreneurship. New York City for example uses revenue from its film and television projects to fund media entrepreneurship efforts like the NYC Media Lab.

New York City’s media and tech startup scene, so-called “Silicon Alley,” is no longer confined to a small alleyway in NYC’s financial district and is more of a concept than a location. Media companies such as Google and IAC/InterActiveCorp make up part of NYC’s media ecosystem. In 2012, the Center for Urban Future proclaimed that NYC witnessed over 1,000 media startups including Tumblr and Mashable.

During this time, NYC was also witnessing the growth of media cooperative working spaces, accelerators and incubators including New York University’s (NYU) Polytechnic Institute Tandon Future Labs supported by the New York City Economic Development Corporation. During this time Mayor Bloomberg advanced tax breaks and funding opportunities for media startups in NYC as part of his five-borough economic plan.

The NYCEDC, in a public-private partnership, also helped launch the NYC Media Lab in 2010. The primary goal of NYC Media Lab is to connect the media industry during the dot-com revival in NYC and colleges and universities in the area to advance media entrepreneurship. The consortium, which includes Columbia University, New York University, The New School, the City University of New York (CUNY), the IESE Business School, and the Pratt Institute, work under the NYC Media Lab umbrella to generate media research and development and advance media entrepreneurship. The Combine serves as NYC Media Lab’s incubator and its main goal is to position NYC as the media capital of the world by advancing and launching “one-of-a-kind” media and communication technologies. Specifically, the Combine aims at supporting and growing media startups from faculty and students from collaborating universities with a high potential to launch. The Combine is funded by the NYCEDC, the Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment, and NYC Media Lab’s corporate members.

Some current projects include an experiment with metadata extraction from book manuscripts for Audible, a market research project for MBA students in New York City on augmented reality products for Hearst Ventures, an augmented reality fellowship in design and engineering through Bloomberg and Lampix, and a virtual reality fellowship for Viacom NEXT.

Many European countries also provide funding for entrepreneurial initiatives. In 2004, the Flemish government established iMinds, a digital research center and business incubator to focus on information and communication technology. The European Union and other European nations routinely fund innovation and entrepreneurial projects.

Applicable Techniques

Content Models

Revenue streams are a common element of most definitions of business models, particularly ones used to address electronic commerce.[20] Many online news business models, historically, have been similar to traditional business models, as subscription, advertising, and transactional are the most common categories of online business models.[21][22]

Advertising and subscription still remain the most dominant forms of revenue streams used in most content business models. Content plays involve the creation and dissemination of content, such as news or entertainment, which users will want to receive.

Here’s an example to help you better understand what I mean by a content company. There’s an excellent episode in the first season of Startup,[23] the podcast about creating a startup from Gimlet Media in which the founders, Alex Blumberg and Matthew Lieber, debate whether Gimlet is a content company or a technology company. In the episode, Gimlet Media thus far has gone the route of being a content company. The company produces content—in this case compelling podcasts—that are then distributed on other technology platforms, such as through Apple or Spotify. If Gimlet became a technology company, it would launch a proprietary podcast-playing platform. For comparison’s sake, Spotify provides a platform for streaming audio but does not produce the content—the music, the songs, the podcasts that play on that platform.

See the additional resources included at the end of this chapter for lists of many revenue streams for many digital media, mobile, and e-commerce companies.

Some of the most common forms of revenue streams used in content companies include:

Subscription

When the newspaper industry moved into online content delivery, many companies initially gave its content away online for free. Within the past decade or so, most newspaper companies have offered digital-only subscriptions and bundled online delivery along with the traditional print product. Within the United States, the leading paywall system was developed by PressPlus. Paywalls offer users a certain number of free page visits, before being blocked with subscription, the primary means to gain additional access.

Many digital media companies that offer content, particularly those that offer content that compete with traditional companies such as newspapers, magazines, and broadcasters, have implemented a Paywall approach. A paywall can be hard where the only way to access the content is to pay for it, usually through a subscription, or soft, where the user is given a certain number of free visits or views per month before being asked to subscribe.

Another common subscription model used for content and technology plays is that of a freemium model. Under a freemium model, access to basic content is free, but users can choose to subscribe to premium content for a fee that provides improved access (such as an ad-free experience) or additional services. The online music streaming service Spotify is a classic example of a freemium model, with basic access to ad-supported music online available for free, with monthly premium subscriptions for a fee. Dropbox is another commonly used digital startup that relies on a freemium model. The cloud-based file storage service offers free storage up to a certain amount, and charges a monthly fee beyond that.

Membership is another subscription model. Under a membership model, the content can either be free or paid, but users who purchase a membership receive perks and bonus materials, exclusive access to supplemental materials, and so forth. In many instances, these content companies have been focused on a certain content form (technology, politics, sports) rather than general interest publications. Musician fan clubs and sporting teams are classic examples of non-digital content entities that excel at offering memberships. That same model is applied to media companies, typically ones that diversify their offerings through some of the other miscellaneous revenue streams discussed later (such as events and conferences; archival data, etc.).

Classic subscriptions, of course, are the most prevalent. Netflix is probably the most well-known media content company that offers access to its content through monthly subscription options. As previously mentioned, some media companies offer subscription access based on content delivery mechanism (online, mobile delivery/web, all access).

Increasingly, more and more entertainment content is being sold through subscription packages, with over-the-top services independent of cablevision subscriptions being offered for individual channels (HBO, Showtime, ESPN) or in packaged bundles (Sling, Hulu, Amazon Prime, etc.).

Advertising

There are various forms of advertising for content and technology companies, with many forms specific to the delivery mechanism and form of the company. Traditional legacy media companies sell local direct advertising (newspapers, broadcasters), classified advertisements, sponsorships (most common in broadcasting) and are part of national advertising networks, among other forms.

Advertising networks are still prevalent for digital media content and technology companies, alongside selling direct advertising on various platforms. Native advertising, the use and sale of microsites dedicated to paid clients, the use of Google AdSense, and the sale of Outbrain-style links to external sites are common on web-based content and technology plays.

Content and technology companies can sell display advertising, search advertising, video ads, text/SMS advertising, mobile and digital forms of advertising, and location-based advertising among other forms, particularly in the mobile space. Content and technology startups can also develop their own proprietary forms of advertising content based on the system. For example, Twitter developed and sold promoted tweets and sponsored ads in its platform. Sponsorships, particularly used in podcasts, are another form of advertising available for content and technology plays.

Mobile advertising (“in-app ads” and “mobile display” ads) and variations of charging for content are the most prominent ways traditional media have sought to monetize content thus far, but there are many other alternative business models under consideration, including free and paid SMS alerts, social media platform distribution, and free applications.

Sponsored Content

One sometimes controversial revenue stream is brand storytelling, or advertisements that are written in the form of articles in the “voice” of the publication, and displayed alongside regular editorial content. Brand-sponsored content typically falls under the larger umbrella of “native advertising” as the ads appear “native” to the environment in which they’re displayed. Many top traditional journalistic outlets have an entire team or division dedicated to creating sponsored content for brands (e.g. New York Times’ T Brand Studio, HuffPost’s Partner Studio, Washington Post’s WP BrandStudio, Conde Nast’s 23 Stories and Forbes’ BrandVoice).

Transactional/e-Commerce

Content and technology plays often employ various forms of transactional, or e-commerce revenue streams. Some of these allow for an in-between option for users who want access to content, whether that be one-time or more, but don’t want a full subscription option. Let’s explore some of the most common.

Micropayments

Micropayments are small payments, typically $5 or less, for an individual piece of content. Every time you buy an individual song from Apple for download, for instance, you’ve made a micropayment. The iPod popularized the consumption of individual forms of music, chiefly song downloads, disaggregating individual song purchases from complete albums.

Virtual currencies can be a form of micropayment, typically employed within videogames or on online platforms, such as Facebook or Twitch, where users are making individual small purchases for virtual items, such as increased game playing ability, items used within game, or donations to other users.

Newspapers, magazines, and other forms of micropayments for news and digital delivery of content were tried unsuccessfully in the late 1990s and early 2000s, with companies like Flooz, Beenz, CyberCash, Bitpass, Peppercoin and DigiCash just a few examples of failed micropayment companies from its first era.

From about 2010 or so onward, additional efforts at micropayments have had varying success, usually within various regions. Blendle, a Dutch-based online news startup, has probably had the most success at selling access to individual news articles and magazine content, both in Europe and the United States.

Kachingle, CarrotPay, Knack.it, and Ganxy are a few other companies that offered various forms of micropayment platforms for content companies to utilize in recent years.

My colleague Jameson Hayes and I developed theoretical modified micropayment models for news and media content that introduce the ability for users to microearn for sharing content in addition to having to micropay for it but there are no functioning platforms that fully execute that conceptual vision.[24][25] Many tend to agree that micropayments must be used in tandem with other revenue streams and can’t alone sustain a media operation.

Failure itself is widely embraced by the entrepreneurial community, as the entrepreneurial process encourages and promotes a series of failures along the way that lessons can be learned from (pivots, etc.) Entrepreneurs have even held annual FailCon conferences in which speakers share entrepreneurial failures and lessons learned in cities around the world.

Failure doesn’t mean an idea can’t be revisited. Micropayments were tried unsuccessfully in the 1990s, but with the advent of Blockchain and Ethereum digital transactions have found more success in recent years. With the creation of browsers like Brave, some predict micropayments and digital transactions to become more mainstream in the not-too-distant future. Management and economics scholars have predicted that blockchain has the potential to transform intellectual property and content licensing, access to information and digital goods, and increase the value of curation of digital content. They envision artists who license music on Apple or Spotify being able to easily track how many times songs are played by consumers, backers on crowdfunding sites obtaining royalties each time a song is played, digital goods priced and delivered using a blockchain for payment, contract enforcement, and authentication.

Some newspapers abandoned early efforts at digital subscriptions and for the better part of two decades the industry norm was free online content. Now, of course, digital content payments have been adapted by many companies. Blockchain enables an easy ability for micropayments to be implemented in a browser where users could pay a single subscription and navigate between different newspapers.

Donations

Some media organizations, such as The Guardian, allow for direct donations from readers. These outlets may make a direct plea on their homepage, or at the beginning or end of articles. Donations are also much more commonly used in nonprofits as outlined in the next chapter, but soliciting donations from users can also be done by for-profit media ventures.

Merchandise

Whether you’re a nascent startup or a more established company, selling merchandise with your company’s brand, name, logo, and slogans can serve as an additional revenue stream in addition to serving marketing purposes. T-shirts, mugs, keychains, and hats are commonly sold merchandise. Google, for example, has a physical store on its main campus that sells all sorts of Google-branded merchandise. Companies can also sell merchandise online.

Some other forms of e-commerce:

Crowdfunding

Crowdfunding, defined as “an open call, essentially through the Internet, for the provision of financial resources either in form of donation or in exchange for some form of reward and/or voting rights in order to support initiatives for specific purposes.” offers a novel way of funding projects.[26]

Crowdfunding involves creators of a project soliciting donations from funders, or backers, of the project, through an online platform that features the project request.

Five basic kinds of crowdfunding models have attained widespread reach: donation-based, pre-purchase-based, reward-based, lending-based, and equity-based.[27] In donation-based crowdfunding, the backers support a particular cause with no expectation of any kind of returns.[28] However, in reward-based crowdfunding, the backers are provided with non-monetary benefits in exchange for their support. Kickstarter and Indiegogo are the most well-known and commonly used rewards-based crowdfunding platforms.

A pre-purchase model is similar to rewards. A backer receives the product the entrepreneur is making, such as a music album. Lending-based crowdfunding platforms offer a loan to small-scale lenders with an expectation for a return on capital investment. For instance, Kiva is the most premier lending crowdfunding platform that operates in 66 countries. Equity-based crowdfunding is that in which the backers receive an equity or stake in the profits of the project they have invested in. The Jumpstart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act of 2012 allowed equity funding in the U.S. for the first time. Title III of this act allows small-sized business owners and entrepreneurs to retail investment that was previously restricted to select accredited investors and potential investors on various Internet-based crowdfunding platforms.

Crowdfunding gained popularity somewhere in the late 2000s. Since then it has shown unprecedented growth and is particularly common among startup entrepreneurs and investors. Circleup, Equity Net, AngelList, and Wefunder are examples of some popular equity-based crowdfunding sites.

Retail/Marketplace

One revenue stream for media startups could come from a “digital retail mall” or “transactional experiences” like shopping purchases through a digital credit card or online payment system.

Group Buying

Popularized and most well-known by the startup Groupon, this method provides discounted deals en masse to groups of consumers who scoop up the coupon-like savings that can be purchased and used at a later date.

Applicable techniques

Technology Plays

Many of the models previously mentioned for content plays (subscription, advertising, and transactional) are also applicable for technology plays, and we’ll discuss some miscellaneous categories beyond the Big Three for both.

One of the considerations for technology plays is the distribution mechanism, whether the product is available online, or mobile, some combination of the two, or neither. If the technology play is an Internet-dependent one, such as an app, then the choices are whether it is accessible through the mobile web (HTML5 is a common tool), or proprietary app stores. If it’s an app, then you must decide whether it will be formatted and available in Apple’s iOS format or Google and Android capability. Many universities and cities hold appathons or hackathons that bring together interdisciplinary teams to work on the creation of an app and/or the business plan and pitch for an app concept over a weekend. These are useful and can help flesh out some of the necessary steps and considerations for startup tech plays. Look for such efforts at your university or city. MediaShift also sponsors a popular hackathon several times a year that brings together students, faculty, and professionals from universities across the country.

If you are creating an app, decisions include whether the download is free or if you charge a one-time download fee. Then, you can consider some of the above-mentioned revenue streams, such as subscription, and mobile advertising.

Some other revenue models commonly employed in technology plays include:

Auction

eBay is probably the most well-known auction site, where users can post items for sale and get bids from other users.

Sharing Economy

Apps and websites that take advantage of the sharing economy have proliferated in recent years. Also referred to as the collaboration economy, this business model is predicated on collaboration, whether that is sharing an apartment or home (as is the case in Airbnb), sharing a ride (Lyft or Uber), or sharing office space (coworking spaces).

Miscellaneous revenue streams for both content and technology plays:

Events/Conferences

Mainstream media outlets like The New York Times excel at organizing live events and conferences as an alternative revenue stream, but startups can also do the same. Media organizations sponsor live events, such as conferences and banquets, and charge a fee to attend.

Foundation Funding

See resources elsewhere in this textbook for lists of foundation funding sources. Many nascent entrepreneurs and media startups have benefited from foundation funding in the past. The Knight Foundation historically has been a large funder of media entrepreneurial efforts. The Lenfest Institute for Journalism is a new funding source for entrepreneurial journalism efforts. And organizations like the Kauffman Foundation and VentureWell fund entrepreneurial efforts writ large. Grants and competition prizes from foundations focusing on entrepreneurship are worth exploring as a funding source.

Sell Archival Access

Content companies who have created archives of past content can sell access to the archives to users for a fee.

Sell Data and/or Analytic Services

Analytics are usually more of a B2B play, where the business sells access to user data and analytics to other companies. In some instances, companies can sell analytic tools and services to users as well.

Licensing

Commonly used in technology plays, licensing as a revenue stream involves licensing out some form of proprietary technology, such as software or analytics tools, for use by other companies for a fee.

Conclusion

This chapter has introduced the concepts of business model, revenue model, and business plan. You should have an understanding of what comprises a business model and business plan, some common revenue streams used in traditional media companies, and revenue streams available for content and technology startup plays, along with the role regulations and government can play among startups. You can start to develop the business model for your startup concept by sketching out the basic idea and its target customer, then identifying how it will make money through one or more revenue streams discussed in this chapter.

Exercise

TRY IT: NAPKIN SKETCH

Sketch out the start of a startup concept on the back of a napkin.

I would encourage doing this assignment after you’ve developed a customer empathy map and have a target customer segment in mind for your concept.

Address the following questions in your napkin sketch:

- What is your idea (concept) and why is it valuable (value proposition)?

- Who will it serve (target customer)?

- How will it make money (revenue streams)?

For the first question, you’ll want to keep it succinct. The equivalent of a 140-character or less tweet is a good starting point. This forces brevity, as does using an actual napkin for this exercise. There’s only so much space on a napkin.

Napkin sketches are a commonly used brainstorming tool. The napkins at Walk-Ons Bistreux and Bar, a sports bar started by Louisiana college basketball players in 2001, include the original napkin sketch for the sports bar concept.

When my Lede, LLC cofounder Jameson Hayes and I first sketched out our idea for a news micropayment business model, we did so on a napkin over beers and fried pickles at the Blind Pig Tavern in Athens, Georgia. While the napkin sketch is somewhat of a cliché, I can attest firsthand that when inspiration hits you have to use whatever you have handy to put it on paper– even if that is in fact an actual napkin.

If your concept is a content play or a technology play, you may want to mention that as well.

The napkin sketch and brainstorming activities, such as the customer empathy map, are good tools to begin the process of formulating a business model for your startup concept. The customer segments and revenue streams are two of the nine blocks for the business model canvas tool anyway.

This chapter has discussed a number of different revenue streams and business models that are ideal for media startup companies. You can pull one or more revenue streams from some of the models mentioned in this chapter for the third question.

Value chiefly what’s referred to as the value proposition, is also important to consider. This directly connects to the customer segments. What value will you offer the customer? Essentially this also addresses the “why?” question. Why you? Why would anyone use this product and/or pay for it? What value is offered?

Before fleshing out additional blocks of the business model canvas, it’s useful to continue to ask and answer a series of questions.

Chris Guillebeau’s book, The $100 Startup, provides a nice resource in the form of the one-page business plan. You’re encouraged to answer each question on the form with one to two short sentences.

Suggested Readings

- Guillebeau, Chris. The $100 Startup: Reinvent the way you make a living, do what you love, and create a new future. Crown Pub, 2012.

- Osterwalder, Alexander, and Yves Pigneur. Business Model Generation: a handbook for visionaries, game changers, and challengers. John Wiley & Sons, 2010.

- Ries, Eric. The Lean Startup: How today’s entrepreneurs use continuous innovation to create radically successful businesses. Crown Books, 2011.

- Maurya, Ash. Running Lean: iterate from plan A to a plan that works. “O’Reilly Media, Inc.,” 2012.

Resources

-

The Ultimate Master List of Revenue Models Used by Web and Mobile Companies[32]

- 76 Ways to Make Money in Digital Media[33]

Geoffrey Graybeal is a clinical assistant professor in the Entrepreneurship and Innovation Institute at Georgia State University. He is a media management scholar and entrepreneur who uses economic and management theory to explore issues of media sustainability. Graybeal teaches courses on media entrepreneurship, media management, media economics, and innovation. Reach him on Twitter at @graybs13.

Leave feedback on this chapter.

- Osterwalder, Alexander; Pigneur, Yves. Business Model Generation (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2013). ↵

- Picard, Robert. “Changing Business Models of Online Content Services: The Implications for Multimedia and Other Content Producers.” International Journal on Media Management 2 (2000): 60-68. ↵

- Osterwalder, Alexander; Pigneur, Yves. "Business Model Canvas," https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Business_Model_Canvas#/media/File:Business_Model_Canvas.png. ↵

- "The Value Proposition Canvas," Strategyzer, https://strategyzer.com/canvas/value-proposition-canvas. ↵

- Hayes, Jameson L and Graybeal, Geoffrey M. “Synergizing Traditional Media and the Social Web for Monetization: A Modified Media Micropayment Model.” Journal of Media Business Studies 8 (2011): 19-44. ↵

- Michelle Ferrier, "Ideation," Media Innovation and Entrepreneurship, https://press.rebus.community/media-innovation-and-entrepreneurship/chapter/ideation-2/. ↵

- Picard, “Changing Business Models,” 60-68. ↵

- Osterwalder and Pigneur, "Business Model Generation." ↵

- "Ad Lib Value Proposition Template," Strategyzer, https://assets.strategyzer.com/assets/resources/ad-lib-value-proposition-template.pdf. ↵

- "Resources," Strategyzer, https://strategyzer.com/platform/resources. ↵

- Johnson, Mark. Seizing the White Space: Business Model Innovation for Growth and Renewal (Boston: Harvard Publishing Company, 2010). ↵

- Küng, Lucy. Strategic Management in the Media: From Theory to Practice. (Los Angeles: Sage, 2008). ↵

- Picard, “Changing Business Models,” 60-68. ↵

- Küng, Lucy, Picard, Robert and Towse, Ruth. The Internet and the Mass Media (Sage: Los Angeles 2008). 153. ↵

- Zott, Christoph and Amit, Raphael. “The Fit Between Product Market Strategy and Business Model: Implications for Firm Performance.” Strategic Management Journal 29 (2008): 1-26. ↵

- Zott, Christoph, Amit, Raphael, and Massa, Lorenzo. “The Business Model: Recent Developments and Future Research.” Journal of Management 37 (2011): 1019-1042. ↵

- CJ Cornell, "Startup Funding," Media Innovation & Entrepreneurship, https://press.rebus.community/media-innovation-and-entrepreneurship/part/startup-funding/. ↵

- Picard, Robert. “Environmental and Market Changes Driving Strategic Planning in Media Firms.” In R.G. Picard (Ed.). Strategic Responses to Media Market Changes 2. (Sweden: Jonkoping International Business School, 2004): 65-82. ↵

- Isenberg, Daniel. "The Entrepreneurship Ecosystem Strategy as a New Paradigm for Economic Policy: Principles for Cultivating Entrepreneurship." Presentation at the Institute of International and European Affairs (2011). ↵

- Laudon, Kenneth C. and Traver, Carol Guercio. E-commerce: Business. Technology. Society (Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall, 2008). ↵

- Graybeal, Geoffrey M. and Hayes, Jameson L. “A Modified News Micropayment Model for Newspapers on the Social Web.” International Journal on Media Management 13 (2011). 129-148. ↵

- Mings, Susan B. and White, Peter B. “Profiting From Online News: the Search for Viable Business Models.” In Internet Publishing and Beyond. Kahin, B. & Varian, H.R. (Eds.) The President and Fellows of Harvard College (2000). ↵

- StartUp podcast, https://gimletmedia.com/startup/. ↵

- Graybeal and Hayes, "Modified News Micropayment Model" ↵

- Hayes and Graybeal, "Synergizing Traditional Media" ↵

- Schwienbacher, Armin and Larralde, Benjamin, Crowdfunding of Small Entrepreneurial Ventures (September 28, 2010). Handbook of Entrepreneurial Finance, Oxford University Press. ↵

- Mitra, Devashis. "The Role of Crowdfunding in Entrepreneurial Finance." Delhi Business Review 13, no. 2 (2012): 67. ↵

- Bradford, C. Steven. "Crowdfunding and the Federal Securities Laws." (2012). ↵

- Strategyzer video series, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wwShFsSFb-Y. ↵

- "Ad Lib Value Proposition Template," Strategyzer, https://assets.strategyzer.com/assets/resources/ad-lib-value-proposition-template.pdf. ↵

- "Web And Mobile Revenue Models (final)," Hackpad, Accessed July 13, 2017. https://hackpad.com/Web-And-Mobile-Revenue-Models-final-EgXuEtSibE7. ↵

- Kumar, Abash, "The Ultimate Master List of Revenue Models Used by Web and Mobile Companies," YourStory.com, March 20, 2014, Accessed July 13, 2017, https://yourstory.com/2014/03/ultimate-master-list-revenue-models-web-mobile-companies/. ↵

- Plotz, David, "76 Ways to Make Money in Digital Media," Slate Magazine, August 29, 2014, Accessed July 13, 2017, http://www.slate.com/blogs/moneybox/2014/08/29/_76_ways_to_make_money_in_digital_media_a_list_from_slate_s_former_editor.html. ↵

The most valuable design sits at the intersection of three questions: can we do this; should we do this; do they want this?

A scenario in which people can use parts of a product for free, but must pay for upgraded functionality or features.