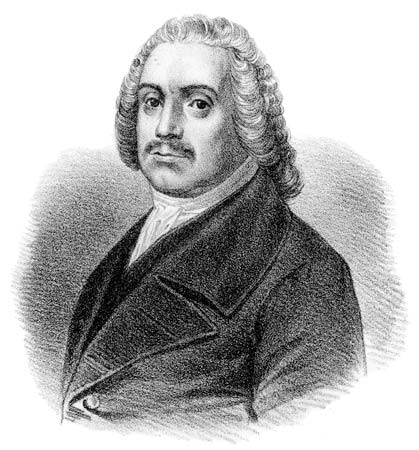

16 Roger Williams (c.1603-1683)

Matt Moore; Ryan Schlom; and Katelyn Metcalf

Introduction

Roger Williams was born in 1603 in London, England to James Williams and Alice Pemberton. The exact date is unknown due to the Great Fire of London in 1666 in which his birth records were burned. During his teenage years, Williams grew up as the protege of well-known jurist, Sir Edward Coke. Coke influenced Williams to attend Charter House in London and then Cambridge University. Williams especially had a knack for different languages and spoke Latin, Greek, and Hebrew. During college, he became a Puritan. He graduated college in 1627.

After graduating, he became a chaplain to the family of a wealthy Puritan gentleman, Sir William Masham. Through Masham, Williams gained connections to Puritans such as Oliver Cromwell and Thomas Hooker. He married Mary Barnard in December of 1629. Together, the couple had six children (all were born later in America).

In 1630, he felt he needed to leave England because of his views on the freedom of worship. On February 5, 1631, he arrived at Boston with Mary. Upon arrival, he denied the invitation to associate with the Anglican Puritans there.

Williams was well-known for his relations with Native Americans and he was one of the first individuals to document and translate a Native American language and ethnographic study in both prose and poetry. In 1632, he moved to the Plymouth Colony, and in the next year returned to Salem when he had a disagreement with the magistrate, claiming that the only fair purchase of land from the Native Americans was a direct purchase.

Because of his views, Williams was banished from the colony. So, in 1636, he set out with his followers to Narragansett Bay where they purchased land (the right way) from the Narragansett Indians, founding a colony in Rhode Island that Williams called the Providence Plantation. Quickly becoming a religious refuge, the colony served as a safe place for Quakers, among others, whose beliefs didn’t really match up with that of the public. In a trip to England to receive a charter for Rhode Island, Williams met and became friends with poet, John Milton.

Until King Philip’s War began in 1675, the Native Americans were peaceful with the English settlers. Rhode Island fell victim to the war, and was burned down.

Williams died in 1683. He is remembered as the founder of Rhode Island, an advocate for the separation of church and state, and for his views on taking land from Native Americans.

Williams’ most famous works were The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution (1644), A Key into the Language of America (1643), and his Letter to the Town of Providence (1655).

A Key into the Language of America

In the first study ever conducted of an Indian language, Roger Williams wrote A Key into the Language of America in 1643. It was published in both New England and, across the Atlantic, in London by Williams’s friend Gregory Dexter. Williams had primarily focused on translating words within the lexicon of the Narragansett tribe which, after the absorption of many of those words into English vernacular, are still used today: moose, squash, and quahog are only a few. Although Williams’s work garnered much attention, it also provoked and jeopardized a deeply ingrained European/Judeo-Christian train of thought and way of life, especially within Williams’s own Puritan communities. This was due to the fact that A Key was as much of a ‘Rosetta Stone’ as it was a work of denouncement towards the Puritans’ perceived superiority relative to the indigenous people. For example, Williams adamantly professes that Europeans and Indians are equal and of the same blood (this is further complicated by Williams’s invocation of his own Christian God to justify this equality). In addition, he challenged the assumptions that the crown was entitled to a right to claim Indian land. This idea that Europeans were equal to the indigenous people was radical for Williams’s time and incited a backlash against him. Moreover, A Key’s multigeneric composition – as a translation, historical document, ethnographic study, and a coalescing of both poetry and prose – proves time and time again that Williams produced an integral, underrated piece of early American literature and socio-political advocacy.

A Key into the Language of America, excerpt (1643)

I once traveled to an island of the wildest in our parts, where in the night an Indian (as he said) had a vision or dream of the sun (whom they worship for a god) darting a beam into his breast which he conceived to be the messenger of his death: this poor native called his friends and neighbors, and prepared some little refreshing for them, but himself was kept waking and fasting in great humiliations and invocations for ten days and nights; I was alone (having traveled from my bark, the wind being contrary) and little could I speak to them to their understandings especially because of the change of their dialect or manner of speech from our neighbors: yet so much (through the help of God) I did speak, of the true and living only wise God, of the creation: of man, and his fall from God, etc. that at parting many burst forth, “Oh when will you come again, to bring us some more news of this God?” . . .

Nature knows no difference between Europe and Americans in blood, birth, bodies, etc. God having of one blood made all mankind, Acts 17, and all by nature being children of wrath, Ephes, 2.

More particularly:

Boast not proud English, of thy birth and blood

Thy brother Indian is by birth as good.

Of one blood God made him, and thee, and all.

As wise, as fair, as strong, as personal.

By nature, wraith’s his portion, thine, no more

Till grace his soul and thine in Christ restore.

Make sure thy second birth, else thou shalt see

Heaven ope to Indians wild, but shut to thee.

The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution

Upon his arrival in New England, Williams was offered numerous jobs and positions within the Church. However, Williams declined countless times on the basis of the new church’s inability to further separate itself from the Church of England, which he viewed as corrupt and degraded. Around 1635, due to Williams’s separatist dissent and challenges towards the Salem church’s foundational doctrines, the magistrate of Massachusetts had prepared to ship Williams back to England. Although Williams avoided this deportation by fleeing into the wilderness near the Narragansett Bay, Salem’s minister John Cotton delivered various sermons which were fraught with an anti-Williams rhetoric. During a brief stay in London around the 1640s, Williams responded to Cotton’s pragmatic belief in enforced religious uniformity. From this endeavor the The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution was composed and finally published in 1644. Most scholars agree that The Tenent is a stylistic and compositional catastrophe, however, within is held one of Williams’s key ideas: the liberty of conscience, or, more commonly known as, freedom of religion. Williams argues for the importance of an interfaith dynamic in society and espouses a Christian duty to understand and accept those from different religious backgrounds and denominations. Later, The Tenent would become an essential source for John Locke and become a large influence on Thomas Jefferson’s idea of freedom of religion and, by extension, the First Amendment.

The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution (1644)

Preface:

First. That the blood of so many hundred thousand souls of protestants and papists, spilt in the wars. of present and former ages, for their respective consciences, is not required nor accepted by Jesus Christ the Prince of Peace.

Secondly. Pregnant scriptures and arguments are throughout the work proposed against the doctrine of persecution for cause of conscience.

Thirdly. Satisfactory answers are given to scriptures and objections produced by Mr. Calvin, Beza, Mr. Cotton, and the ministers of the New English churches, and others former and later, tending to prove the doctrine of persecution for cause of conscience.

Fourthly. The doctrine of persecution for cause of conscience, is proved guilty of all the blood of the souls crying for vengeance under the altar.

Fifthly. All civil states, with their officers of justice, in their respective constitutions and administrations, are proved essentially civil, and therefore not judges, governors, or defenders of the spiritual, or Christian, state and worship.

Sixthly. It is the will and command of God that, since the coming of his Son the Lord Jesus, a permission of the most Paganish, Jewish, Turkish, or anti-christian consciences and worships be granted to all men in all nations and countries: and they are only to be fought against with that sword which is only, in soul matters, able to conquer: to wit, the sword of God’s Spirit, the word of God.

Seventhly. The state of the land of Israel, the kings and people thereof, in peace and war, is proved figurative and ceremonial, and no pattern nor precedent for any kingdom or civil state in the world to follow.

Eighthly. God requireth not an uniformity of religion to be enacted and enforced in any civil state; which enforced uniformity, sooner or later, is the greatest occasion of civil war, ravishing of conscience, persecution of Christ Jesus in his servants, and of the hypocrisy and destruction of millions of souls.

Ninthly. In holding an enforced uniformity of religion in a civil state, we must necessarily disclaim our desires and hopes of the Jews’ conversion to Christ.

Tenthly. An enforced uniformity of religion throughout a nation or civil state, confounds the civil and religious, denies the principles of Christianity and civility, and that Jesus Christ is come in the flesh.

Eleventhly. The permission of other consciences and worships than a state professeth, only can, according to God, procure a firm and lasting peace; good assurance being taken, according to the wisdom of the civil state, for uniformity of civil obedience from all sorts.

Twelfthly. Lastly, true civility and Christianity may both flourish in a state or kingdom, notwithstanding. the permission of divers and contrary consciences, either of Jew or Gentile.

To the Right Honorable Both Houses of the High Court of Parliament:

Right Honorable and Renowned Patriots,

Next to saving of your souls in the lamentable shipwreck of mankind, your task as Chrsitans is to save the souls, but as magistrates the bodies and goods, of others. . . .

Two things your honors here may please to view, in this controvsersy of persecution for cause of conscience, beyond what is extant.

First, The whole body of this controversy formed and pitched in true battalia.

Secondly, . . . your Honours shall see the controversy is discussed with men as able as most, eminent for ability and piety — Mr. Cotton, and the New England ministers. . . .

Right Honourable, soul yoke, soul oppressions, plunderings, ravishings, &c., are of a crimson and deepest dye., and I believe the chief of England’s sins — unstopping the vials of England’s present sorrows. . . .

Thirdly. [That] whatever way of worshipping God your own consciences are persuaded to walk in, yet, from any bloody act of violence to the consciences of others, it may never be told at Rome nor Oxford, that the parliament of England hath committed a greater rape than if they had forced or ravished the bodies of all the women in the world.

Chapter 3: [excerpt]

. . . I acknowledge that to molest any person, Jew or Gentile, for either professing doctrine, or practising worship merely religious or spiritual, it is to persecute him; and such a person, whatever his doctrine or practice be, true or false, suffereth persecution for conscience.

But withal I desire it may be well observed, that this distinction is not full and complete. For beside this, that a man may be persecuted because he holdeth or practiseth what he believes in conscience to be a truth, as Daniel did, for which he was cast into the lions’ den, Dan. vi. 16, and many thousands of Christians, because they durst not cease to preach and practise what they believed was by God commanded, as the apostles answered, Acts iv. and v., I say, besides this, a man may also be persecuted because he dares not be constrained to yield obedience to such doctrines and worships as are by men invented and appointed. So the three famous Jews, who were cast into the fiery furnace for refusing to fall down, in a nonconformity, to the whole conforming world, before the golden image, Dan. iii. 21.5 So thousands of Christ’s witnesses, and of late in those bloody Marian days, have rather chosen to yield their bodies to all sorts of torments, than to subscribe to doctrines, or practise worships, unto which the states and times (as Nebuchadnezzar to his golden image) have compelled and urged them.

A chaste wife will not only abhor to be restrained from soul in God’s worship, like her husband’s bed as adulterous and polluted, but also abhor (if not much more) to be constrained to the bed of a stranger. And what is abominable in corporal, is much more loathsome in spiritual whoredom and defilement.

The spouse of Christ Jesus, who could not find her soul’s beloved in the ways of his worship and ministry, . . . abhorred to turn aside to other flocks, worships, &c., and to embrace the bosom of a false Christ. . . .

Chapter 9: [excerpt]

. . . Breech of civil peace may arise when false and idolatrous practices are held forth, and yet no breach of civil peace from the doctrine or practice, or the manner of holding forth, but from that wrong and preposterous way of suppressing, preventing, and extinguishing such doctrines or practices by weapons of wrath and blood, whips, stocks, imprisonment, banishment, death, &c.; by which men commonly are persuaded to convert heretics, and to cast out unclean spirits, which only the finger of God can do, that is, the mighty power of the Spirit in the word.

Hence the town is in an uproar, and the country takes the alarm to expel that fog or mist of error, heresy, blasphemy, as is supposed, with swords and guns. Whereas it is light alone, even light from the bright shining Sun of Righteousness, which is able, in the souls and consciences of men to dispel and scatter such fogs and darkness.

Chapter 16: [excerpt]

And this is the more carefully to be minded, because whenever a toleration of others’ religion and conscience is pleaded for, such as are (I hope in truth) zealous for God, readily produce plenty of scriptures written to the church, both before and since Christ’s coming, all commanding and pressing the putting forth of the unclean, the cutting off the obstinate, the purging out the leaven, rejecting of heretics. As if because briars, thorns, and thistles may not be in the garden of the church, therefore they must all be plucked up out of the wilderness. Whereas he that is a briar, that is, a Jew, a Turk, a pagan, an anti-christian, today, may be, when the word of the Lord runs freely, a member of Jesus Christ tomorrow, cut out of the wild olive and planted into the true.

Mr. Cotton’s Letter, Lately Printed, Examined and Answered.

. . . After my public trial and answers at the general court, one of the most eminent magistrates, whose name and speech may by others be remembered, stood up and spake:

“Mr. Williams,” said he, “holds forth these four particulars:

“First, That we have not our land by patent from the king, but that the natives are the true owners of it, and that we ought to repent of such a receiving it by patent.”

“Secondly, That it is not lawful to call a wicked person to swear, [or] to pray, as being actions of God’s worship.

“Thirdly, That it is not lawful to hear any of the minsters of the parish assemblies in England

“Fourthly, that the civil magistrate’s power extends only to the bodies, and goods, and outward state of men, &c.

I acknowledge the particulars were rightly summed up, . . . I shall be ready for the same grounds not only to be bound and banished, but to die also in New England, as for most holy truths of God in Christ Jesus.

Roger Williams to the Town of Providence

In this brief letter to the town of Providence, Williams, again, preaches for what he calls a “liberty of conscience.” Although Williams draws upon specific, concrete examples – “papists, Protestants, Jews, [and] Turks” – the letter relies heavily on a savvy use of symbolism and extended metaphor. The imagery of a ship at sea (representing a society) and the diverse crew and passengers aboard (citizens and individuals subscribing to different faiths and religious denominations, or none at all) offers an insight into the turbulent forces at work within politics and religion. Williams’s letter illustrates the power literature holds in unveiling the injustices of a world in a concise and poetic fashion. In Williams’s case, and lifelong fight, this would take the form of separation of church and state and the empathy and human understanding required in accepting those from all different walks of life. An issue he not only observed within interfaith dynamics, but also cultural collisions between European settlers and the indigenous people amidst the colonization of America.

A Letter to the Town of Providence (1655)

That ever I should speak or write a tittle, that tends to such an infinite liberty of conscience, is a mistake, and which I have ever disclaimed and abhorred. To prevent such mistakes, I shall at present only propose this case: There goes many a ship to sea, with many hundred souls in one ship, whose weal and woe is common, and is a true picture of a commonwealth, or a human combination or society. It hath fallen out sometimes, that both papists and protestants, Jews and Turks, may be embarked in one ship; upon which supposal I affirm, that all the liberty of conscience, that ever I pleaded for, turns upon these two hinges–that none of the papists, protestants, Jews, or Turks, be forced to come to the ship’s prayers of worship, nor compelled from their own particular prayers or worship, if they practice any. I further add, that I never denied, that notwithstanding this liberty, the commander of this ship ought to command the ship’s course, yea, and also command that justice, peace and sobriety, be kept and practiced, both among the seamen and all the passengers. If any of the seamen refuse to perform their services, or passengers to pay their freight; if any refuse to help, in person or purse, towards the common charges or defence; if any refuse to obey the common laws and orders of the ship, concerning their common peace or preservation; if any shall mutiny and rise up against their commanders and officers; if any should preach or write that there ought to be no commanders or officers, because all are equal in Christ, therefore no masters nor officers, no laws nor orders, nor corrections nor punishments;–I say, I never denied, but in such cases, whatever is pretended, the commander or commanders may judge, resist, compel and punish such transgressors, according to their deserts and merits. This if seriously and honestly minded, may, if it so please the Father of lights, let in some light to such as willingly shut not their eyes.

I remain studious of your common peace and liberty.

Research and Discussion Questions for Roger Williams

The first two questions listed are intended to be “in class” discussion questions, answerable without need for further reading/research. The following three address research interests and may require further reading.

- Roger Williams is someone who we credit with America’s – and now, really, the West’s – governing philosophy that separates the church and the state. How did his actions embody the spirit that seeks to separate the church and state? Where is it reflected in his writings?

- By establishing the Providence Plantation, Williams set a precedent for political resistance based on morality in the country’s early history that numerous other early American authors followed. Name one such author, their text, and discuss their conscience-centered resistance.

- As evidenced in his “A Key Into the Language of America,” Williams respected the American natives – certainly more so than the majority of his contemporaries did. How does the relationship that he draws between Europeans and American natives in “A Key” interact with the statement he makes in “A Letter to the Town of Providence”?

- In what ways did Roger Williams influence, or even give rise to, the fragmented, multi-denominational tradition of Christianity in America?

- Chapter ten of “A Fellowship of Differents: Showing the World God’s Design for Life Together” should give anyone interested in exploring this question a good place to start. (https://books.google.com/books?id=CfN9BAAAQBAJ&pg=PT70&lpg=PT70&dq=roger+williams+and+thoreau&source=bl&ots=vIIAMTFc2s&sig=B19TinnCBb6k_XEcu315CVrNlTY&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwilu7aY-ODQAhXCzFQKHQQ3A9wQ6AEIKzAC#v=onepage&q=roger%20williams%20and%20thoreau&f=false)

- Long (and still) a tricky thing for America and once even a dicey concept to Roger Williams, tolerance is a presiding theme in his writing. Two of his texts, published within a year of each other (A Key, 1643, and Bloudy Tenet, 1644), though focused on two different subjects, share an important intersection at that theme: tolerance. Compare his arguments for cultural and religious tolerance in those two texts.

- This article (title: A Key into The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution: Roger Williams, the Pequot War, and the Origins of Toleration in America, author: Stern, Jessica), which can be found in the MLA International Bibliography, is a good place to look for inspiration.

References

http://www.history.com/topics/roger-williams

https://www.nps.gov/rowi/learn/historyculture/philipswar.htm

http://www.rogerwilliams.org/biography.htm

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Roger-Williams-American-religious-leader