Thou ill-form'd offspring of my feeble brain, Who after birth did'st by my side remain, Till snatcht from thence by friends, less wise than true, Who thee abroad expos'd to public view, Made thee in rags, halting to th' press to trudge, Where errors were not lessened (all may judge). At thy return my blushing was not small, My rambling brat (in print) should mother call. I cast thee by as one unfit for light, Thy Visage was so irksome in my sight, Yet being mine own, at length affection would Thy blemishes amend, if so I could. I wash'd thy face, but more defects I saw, And rubbing off a spot, still made a flaw. I stretcht thy joints to make thee even feet, Yet still thou run'st more hobbling than is meet. In better dress to trim thee was my mind, But nought save home-spun Cloth, i' th' house I find. In this array, 'mongst Vulgars mayst thou roam. In Critics' hands, beware thou dost not come, And take thy way where yet thou art not known. If for thy Father askt, say, thou hadst none; And for thy Mother, she alas is poor, Which caus'd her thus to send thee out of door.

17 Anne Bradstreet (1612-1672)

Shana Rowe

Introduction

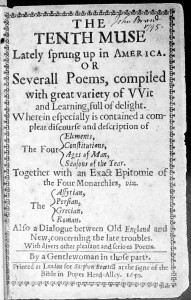

Anne Bradstreet was a distinguished English poet and the first female Colonialist to be published. Bradstreet (neé Anne Dudley) was born on March 20th, 1612 in Northampton England. Bradstreet was born into a prominent and wealthy Puritan family, allowing her to grow up in a cultured environment where she was tutored in history, literature and language. Bradstreet was an extremely well-educated young woman, especially for her time when education was a field reserved specifically for men. At the age of sixteen Bradstreet married Simon Bradstreet (who would later become the governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony) and shortly thereafter in 1630 Bradstreet, her husband and family left for Massachusetts. After their arrival to Cambridge, Massachusetts (which at the time as named Newe Towne) Bradstreet gave birth to her first child Samuel in 1632. Throughout her life Bradstreet gave birth to eight children. Due to the credibility of her husband and father, Bradstreet achieved a high social standing within the town and lived a very comfortable life. Bradstreet’s life, in accordance to the social standards and expectations of the time, would have been considered extremely successful based off of her husband’s achievements and her ability to bear eight children. Bradstreet, however, being an educated woman wanted more for herself and presumably felt it was important for her to express herself. Bradstreet’s poetry is incredibly groundbreaking for its time and deals with issues such as politics, medication, history and religion. One of the major themes throughout her poetry is the role of Puritan women. Bradstreet often questions the social expectations of Puritan women by using metaphors and a sarcastic tone. For example, in her poem The Prologue, Bradstreet sarcastically notes that many men may believe her hand, as a woman, is not fit to be a writer but rather say “my hand a needle better fits” (Bradstreet). Due to the fact that Bradstreet’s poetry was so brazen not only because she was a woman but because of the subject matter as well, Bradstreet’s brother in law, Reverend John Woodbridge, felt it was necessary to include a preface in her first published book of poems (which was published in London in 1647) called The Tenth Muse, Lately Sprung Up in America, By a Gentlewoman in those parts.

Woodbridge, in his preface, essentially convinces readers (who were presumably mostly male) that Bradstreet is a well behaved lady whose main concerns are her husband and household and that her poetry is written only in her free time. The Tenth Muse…is the only book of Bradstreet’s poems to be published during her lifetime. Bradstreet died on September 16th, 1672 at the age of sixty. Shortly after her death in 1678, her self-revised book of poetry called Several Poems Compiled with Great Variety of Wit and Learning…is published. Bradstreet was an incredibly prominent figure in literature due not only to her talent but also to her audacious ability to speak out against the societal norms of women. Bradstreet certainly helped to change the expectations of women and made it more acceptable for women to seek out an education and to express themselves artistically.

The Author to Her Book

The Flesh and the Spirit

In secret place where once I stood

Close by the Banks of Lacrim flood,

I heard two sisters reason on

Things that are past and things to come.

One Flesh was call’d, who had her eye

On worldly wealth and vanity;

The other Spirit, who did rear

Her thoughts unto a higher sphere.

“Sister,” quoth Flesh, “what liv’st thou on

Nothing but Meditation?

Doth Contemplation feed thee so

Regardlessly to let earth go?

Can Speculation satisfy

Notion without Reality?

Dost dream of things beyond the Moon

And dost thou hope to dwell there soon?

Hast treasures there laid up in store

That all in th’ world thou count’st but poor?

Art fancy-sick or turn’d a Sot

To catch at shadows which are not?

Come, come. I’ll show unto thy sense,

Industry hath its recompence.

What canst desire, but thou maist see

True substance in variety?

Dost honour like? Acquire the same,

As some to their immortal fame;

And trophies to thy name erect

Which wearing time shall ne’er deject.

For riches dost thou long full sore?

Behold enough of precious store.

Earth hath more silver, pearls, and gold

Than eyes can see or hands can hold.

Affects thou pleasure? Take thy fill.

Earth hath enough of what you will.

Then let not go what thou maist find

For things unknown only in mind.”

Spirit

Be still, thou unregenerate part,

Disturb no more my settled heart,

For I have vow’d (and so will do)

Thee as a foe still to pursue,

And combat with thee will and must

Until I see thee laid in th’ dust.

Sister we are, yea twins we be,

Yet deadly feud ‘twixt thee and me,

For from one father are we not.

Thou by old Adam wast begot,

But my arise is from above,

Whence my dear father I do love.

Thou speak’st me fair but hat’st me sore.

Thy flatt’ring shews I’ll trust no more.

How oft thy slave hast thou me made

When I believ’d what thou hast said

And never had more cause of woe

Than when I did what thou bad’st do.

I’ll stop mine ears at these thy charms

And count them for my deadly harms.

Thy sinful pleasures I do hate,

Thy riches are to me no bait.

Thine honours do, nor will I love,

For my ambition lies above.

My greatest honour it shall be

When I am victor over thee,

And Triumph shall, with laurel head,

When thou my Captive shalt be led.

How I do live, thou need’st not scoff,

For I have meat thou know’st not of.

The hidden Manna I do eat;

The word of life, it is my meat.

My thoughts do yield me more content

Than can thy hours in pleasure spent.

Nor are they shadows which I catch,

Nor fancies vain at which I snatch

But reach at things that are so high,

Beyond thy dull Capacity.

Eternal substance I do see

With which inriched I would be.

Mine eye doth pierce the heav’ns and see

What is Invisible to thee.

My garments are not silk nor gold,

Nor such like trash which Earth doth hold,

But Royal Robes I shall have on,

More glorious than the glist’ring Sun.

My Crown not Diamonds, Pearls, and gold,

But such as Angels’ heads infold.

The City where I hope to dwell,

There’s none on Earth can parallel.

The stately Walls both high and trong

Are made of precious Jasper stone,

The Gates of Pearl, both rich and clear,

And Angels are for Porters there.

The Streets thereof transparent gold

Such as no Eye did e’re behold.

A Crystal River there doth run

Which doth proceed from the Lamb’s Throne.

Of Life, there are the waters sure

Which shall remain forever pure.

Nor Sun nor Moon they have no need

For glory doth from God proceed.

No Candle there, nor yet Torch light,

For there shall be no darksome night.

From sickness and infirmity

Forevermore they shall be free.

Nor withering age shall e’re come there,

But beauty shall be bright and clear.

This City pure is not for thee,

For things unclean there shall not be.

If I of Heav’n may have my fill,

Take thou the world, and all that will.’

References

“Anne Bradstreet.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 05 Oct. 2015. Web. 06 Oct. 2015.

Pechman, Alexandra, and Anne Bradstreet. “Prologue.” Poetry Foundation. Poetry Foundation, 2015. Web. 06 Oct. 2015.