Supporting Open Textbook Creation

17 Hosting and Sharing OER

Stefanie Buck

Your OER project will need a home or “host,” which is someplace where you can store your OER project files so others can access, reuse, and remix them, and so that repositories or referatories can link to them for discoverability. You will need to consider what technical formats you will offer the OER in so you can determine where and how to store them. Discoverability and reusability of your OER content are central to being open and can prove to be challenging for OER creators (Amiel 2013; Ovadia 2019).

Where Will You Host the Project?

How and where the OER projects reside and are delivered for use once they are completed is a decision that needs to be considered sooner rather than later (Cuillier et al. 2016). It will impact what you are able/willing to host (and how) and may also have implications for the formats you can accept from your faculty authors. For example, if you are using Pressbooks as your hosting platform, it may be easiest for faculty authors to provide a Word, XML or ePub format. PDF documents, on the other hand, won’t translate well into Pressbooks and should be avoided. And don’t forget about ancillary materials such as videos, slide decks, and question banks, which will need a home as well and in some way connect to the original OER.

OER delivery mechanisms can be divided into three categories:

- Repository: A centralized site that stores the OER locally (e.g., an institutional repository)

- Referatory: a portal or directory that links to the OER and provides the metadata to help locate these resources (e.g., Open Textbook Library)

- A combination of the two (Brahmin, Khribi, and Jemni 2018; McGreal 2017)

Reusability and Revisabillity of Content

Making content available as well as reusable and revisable are major tenants of the open movement. Ovadia (2019) notes that there are technical challenges to overcome. As project manager, you will want to take these into consideration. One is the reusability of the content (can it be downloaded as opposed to just viewed) and if the file format is editable (remixable and revisable) by anyone, not just individuals who have access to proprietary software (Ovadia 2019).

Storing OER Locally

There are many options when considering where to host, but working with what you already have at your institution is certainly a good place to start. Hosting requires technical support and possibly financial support, so rather than starting from scratch, checking with your institution on what is already available can save you time and money.

Local hosting means that the server storing your content is located and managed by you or someone at your institution on site. It could also mean having to manage a server where your content lives, including running system updates and security patches. Hosting locally gives you control over the content but also means you are potentially responsible for everything to do with the server maintenance.

One option is to use your local institutional repository (IR). IRs are quite popular at academic institutions for hosting locally produced materials, usually papers, theses, dissertations, etc. created by the faculty and student authors at the institution. Often, these IRs are managed by the university library. An institutional repository can offer some advantages. One is that it’s often possible to customize metadata (the information that describes your OER). Another advantage is more access points (e.g., your content is findable by title, author, content type, etc.). An IR also needs care and maintenance, although that will not necessarily fall on you. One place to begin is to check with your institution’s library to see if you can use the IR to host your content. This can get tricky if you have many different types of media in your OER, but most IRs can handle the better-known formats.

Examples of institutions that use their university’s IR for their OER include:

Some also create separate OER repositories using the same IR software but not necessarily mixed in with other IR materials such as open articles. Examples of this include:

Another option is to use LibGuides as your hosting platform. Many academic libraries have access to this resource and it’s WYSIWYG content development interface makes it easy to create new sites. However, there may be limitations to using LibGuides so this solution may not work in all instances (Georgia Southern University).

Hosted Solutions

A publishing platform like Pressbooks can act as a hosting space, whether or not the server itself is maintained in-house or if you are outsourcing. The term for this type of hosted service is Software as a Service, abbreviated as SaaS. SaaS is usually built on a licensing model where the access to the necessary software (e.g., Pressbooks) is provided on a subscription basis. The software itself is located on external servers. Platforms that offer hosting are useful because they provide the front end—search function, metadata, search engine optimization—to not only store your content but also make it accessible and discoverable. In many cases, you can either host the platform on-site on a local server or have the platform publisher manage the server for you (usually for a fee). One advantage, however, is that the care and maintenance of the server are done by someone else. Sometimes, as with other software, you can get a free trial or use a free version of the hosting solution as a way to test which platform/hosting solution will work best for you.

There are some institutions that use shared storage services to host their content; Google Drive, Box, and GitHub are among the more common ones. For other media formats, Kaltura, YouTube, Slideshare, or similar platforms can be used. These have the advantage of being open, and many universities have a shared storage solution already in place. However, these solutions may not allow for search engine optimization (SEO), metadata, and search engine functionality, such as being able to search by author or title, unless specifically created. There still needs to be a way to find this content, even if it is stored on a local server.

Portals and Directories/Referatories

There are other ways to host the content elsewhere if you do not have the technical support to do it in-house. There are a few repositories that will actually host your content and/or act as your content creation system.

Platforms and repository combinations:

Outsourcing your content also has some potential drawbacks. One thing to consider is what will happen to your content should the repository go away or no longer be maintained. A recent example is Florida’s Orange Grove, which lost funding and was shut down in 2020. If you are hosting locally, you should be OK as long as the server support is there. But if you are hosting somewhere not under your control, it is something that you need to consider (and always have a local backup).

Remember that the hosting platform, whether it is local or external, can inadvertently create a barrier to access (e.g., needs too much bandwidth, material is hard to download or discover), so consider those issues as you select your platform. Simple is usually better or you might consider offering a low-bandwidth version of your OER if you find it necessary. Remember that in order for your OER to be remixable and revisable, they need to be in an editable format and the user needs to be able to download editable source material. Without this ability, a “license offers only theoretical rights” (Ovadia 2019).

How Do You Share What Has Been Created?

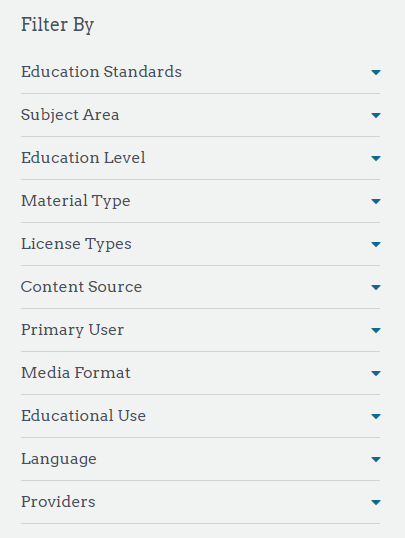

Most repositories or portals don’t actually host your content; they just point to it. These types of platforms might more precisely be called referatories since your content actually lives elsewhere. An example here is the Open Textbook Library, which is a very large referatory of OER content. It provides the search interface and metadata to make your OER findable. Another is OER Commons, which both hosts and points to OER resources. Both referatories ask you to submit content for review; you need to actually submit a link to where your content is stored to these referatories, since it won’t find its way in there automatically.

If one exists, you may also want to consider submitting your metadata to a subject-specific repository, such as Humanities Commons. These are a little harder to find and may not be as well-known, but specialists in the field or discipline may know of or already use these. Most likely you will want to submit your content to several repositories or referatories for maximum exposure. Keep track of this in case you need to upload a new edition or version of the OER.

Metadata for OER

“Metadata are the key elements for repositories to represent and organize educational resources” (Mouriño-García et al. 2018). The term ”metadata” refers to the descriptive data about your OER, such as the author, title, date created, format, length, license (e.g., Creative Commons), etc. Keep in mind that most people use a basic search engine to find OER and few people use the advanced search functions to refine their searches (Dichev and Dicheva 2012). Currently, there are no agreed-upon metadata standards for OER repositories. Different repositories may have different metadata standards, although there are some better-known schemas, such as IEEE Learning Object Metadata (LOM), ISO/IEC MLR, or Dublin Core Metadata (Mouriño-García et al. 2018). Because each repository is unique, you will likely use the metadata standard of the hosting platform. Be sure to fill in as much of the metadata as you can. It will improve the discoverability of your resources.

Keep in mind that you will need to generate some of the metadata for your resources, such as determining the appropriate subject headings. This can take some time and should be a part of your workflow (Mouriño-Garcia et al. 2018).

Dissemination

Dissemination for use and reuse is a key element of OER. Yes, there are faculty who have created wonderful free course materials but have them behind a firewall (e.g., a learning management system). OER created within your program (e.g., potentially funded by a grant) need to be openly available to be truly OER. How will you get the OER out into the world? This is where large repositories and referatories like OER Commons or the Open Textbook Library and meta-search engines like Mason OER Metafinder (MOM) are very useful. While there is, at the time of this writing, no place that stores/hosts/amalgamates all the OER out there into one easy-to-use searchable database, there are some larger repositories, referatories, and search engines that are serving that purpose in an ad hoc way. In order for people to find your content, you will want to make sure your OER materials are represented in these repositories or referatories.

Unfortunately, using Google to search for OER is less than satisfactory, although there is search engine optimization you can do to improve how your OER displays in a Google search. But if you have ever tried a search like “Analytical chemistry OER” (559,000 results as of this writing!), you’ll know how overwhelming the results can get. A major faculty complaint is that they cannot find viable OER for their course (chances are they are searching Google). A repository or referatory generally allows for more refined searching and therefore more satisfactory results, so you will want your content to be well represented in the repositories/referatories your faculty might use to find OER content.

Getting OER into the Library Catalog

It is also helpful to consider your local library catalog or discovery system. This is where users search for content that is available to them, and having your OER materials—especially textbooks—included in the library catalog is one way to help students and faculty discover what is available to them. Work with your library’s course reserves services or technical services department (cataloging) to make your OER findable. Here again, there will be metadata requirements, so it’s best to know what you need before you start. Sobotka, Wheeler, and White (2019) highlight some of the challenges of getting OER into a library catalog, and their article is worth reviewing if you plan to do this.

Metrics

When you add your material to a repository or referatory, check to see what kind of usage statistics or metrics you can get. Downloads, shares and views are one good indicator of the impact the OER is having outside the institution. Faculty will appreciate having this information available to them to improve their content but also demonstrate the impact of their work, especially in the promotion and tenure process. Most repositories or referatories will provide you with the number of views and/or downloads but some will also provide your faculty author with alt-metrics, such as the number of times a resource has been tweeted and retweeted. You may not always know how the OER is being used but you can certainly find out where and when it is being used. It will also be useful for you to collect this data for reporting purposes.

Marketing Your OER

Once your project is complete, you may want to provide your faculty with some marketing tools to help them share their work. For example, a one-page flyer announcing the publication of the work or a notice to a list such as LibOER or subject-specific lists can help spread the word about the new resource. If your library or institution has a social networking presence or even a marketing department, an announcement here will raise awareness of the resource as well as the work of your unit or department.

Conclusion

There are many ways to host and share your OER. You can either host your resources locally or have them hosted for you. Either option will probably incur some costs, so keep that in mind as you decide on the hosting solution that is best for you. Dissemination of your OER is also key to making your content findable and reusable. You will want to make your OER as widely available as possible. You can do this by submitting it to a variety of referatories and repositories so that they are easily found. Remember that these referatories and repositories generally require that you submit the OER to them; they won’t automatically add your content. It’s also useful as the project manager to think about how you might market your OER. This is often overlooked but is important to get as wide a reach as possible. And don’t forget to add your OER to the library catalog or discovery system at your institution.

Recommended Resources

- Leveraging Cataloging and Collection Development Expertise to Improve OER discovery (Sobotka, Wheeler, and White 2019)

- Think about how and where you want to make your OER available. This could be locally, for example, in an institutional repository or in a repository/referatory such as OER Commons. A good strategy will likely consist of a bit of all these suggestions. For maximum dissemination, submitting to multiple repositories and referatories as well as hosting your own gives you maximum exposure. One of the advantages of OER is that many copies can be created and live in multiple spaces so don’t limit yourself to only one.

- People need to be able to find your resources before they can use them. Think about including your OER in your library’s catalog or discovery system.

- Make sure you have enough metadata to make your OER findable. Metadata requirements will differ from repository to repository or referatory to referatory. Learn about what metadata is needed for each repository/referatory where you plan to submit your OER.

- Market your OER. Send out announcements and flyers. For example, you could have a book launch. After all, you’ve worked hard so you want as many people as possible to know about your work.

References

Amiel, Tel. 2013. “Identifying Barriers to the Remix of Translated Open Educational Resources.” The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 14 (1): 126–44. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v14i1.1351

Brahmin, Hejer Ben, Mohamed Koutheair Khribi, and Mohamed Jemni. 2018. “Towards Accessible Open Educational Resources: Overview and Challenges.” In 2017 6th International Conference on Information and Communication Technology and Accessibility (ICTA). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICTA.2017.8336068

Cuillier, Cheryl, Amy Hofer, Annie Johnson, Kathleen Labadorf, Karen Lauritsen, Peter Potter, Richard Saunders, and Anita Walz. 2016. Modifying an Open Textbook: What You Need to Know. Open Education Network. https://oen.pressbooks.pub/oenmodify/

Dichev, Christo, and Darina Dicheva. 2012. “Is it Time to Change the OER Repositories Role?” Proceedings of the 12th ACM/IEEE-CS joint conference on Digital Libraries – JCDL ’12: 31–34. https://doi.org/10.1145/2232817.2232826

Georgia Southern University. “Creating and Hosting OER using Libguides: LibGuides Pros and Cons.” https://georgiasouthern.libguides.com/c.php?g=1059406&p=7700307

McGreal, Rory. 2017. “Special Report on the Role of Open Educational Resources in Supporting the Sustainable Development Goal 4: Quality Education Challenges and Opportunities.” The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(7). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i7.3541

Mouriño-García, Marcos, Roberto Pérez-Rodríguez, Luis Anido-Rifón, Manuel Fernández-Iglesias, and Victor M. Darriba-Bilbao. 2018. “Cross-Repository Aggregation of Educational Resources.” Computers & Education 117: 31–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.09.014

Ovadia, Steven. 2019. “Addressing the Technical Challenges of Open Educational Resources.” portal: Libraries and the Academy 19 (1): 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2019.0005

Sobotka, Clare, Holly Wheeler, and Heather White. 2019. “Leveraging Cataloging and Collection Development Expertise to Improve OER Discovery.” OLA Quarterly 25 (1): 17–24. https://doi.org/10.7710/1093-7374.1971