Supporting Open Textbook Creation

20 Project Management

Apurva Ashok and Stefanie Buck

Project management is integral to the role of a program manager. Broadly defined, project management includes “planning, putting the project plan into action, and measuring progress and performance” (Watt 2014). As the project manager, you must oversee each stage of a project’s development by applying relevant knowledge, tools, and techniques to meet given conditions and requirements (Watt 2014). These project management skills are also critical for anyone leading initiatives that support OER creation.

Project Management for OER

OER projects are highly variable and require an adaptable management approach. Each OER project is unique and differs in its goals, outcomes, and team composition. A project can range in size and complexity. For example, you may have an author publishing an open textbook or creating ancillary materials for an existing book. Or you may have an author adopting a text or creating a new course using open pedagogy. Each of these projects is unique and requires different time and resource commitments.

OER projects are rarely the work of just one individual. OER teams typically consist of you, the project manager, the author(s) (both faculty and students), and possibly instructional designers, librarians, and/or technologists across multiple offices at an institution, hopefully with the support of at least one senior administrator. Your team members’ motivations are dynamic, converging on some points and diverging on others (Langille 2019). As a project manager, you will need to guide teams toward their desired results, introduce them to open concepts and approaches, supervise their work, help navigate the challenges of OER creation or remixing, and steer them toward project completion.

It is not our intention to create a complete project management chapter in this book; there are other resources that can help you with the stages of project management. We’ve gathered our best tips and resources based on our experiences as project managers to equip you with the skills to efficiently accomplish the tasks ahead, bring the project to fruition, and assess the results.

Pause and Get Situated

Project management work can be very fast-paced and overwhelming, depending on the rhythm and number of the projects you are supporting. A good place to start is by taking a moment before initiating any projects to familiarize yourself with the network, tools, resources, and landscape of OER more broadly and within your institution. Conduct an environmental scan of your institution’s relationship with OER, and learn about the key tenets of open education and OER (See Chapter 8, Building Familiarity of Campus for guidance on conducting an environmental scan). Familiarize yourself with the major OER repositories and referatories, such as OpenStax and the Open Textbook Library, and the major support networks such as the Open Education Network and the Rebus Community. At the same time, begin building networks and relationships with your colleagues and others in the open education community. Some opportunities for networking and professional development include campus mentorship programs, networking events, and library- and OER-related conferences such as Open Education Global or the Open Education Conference. If your institution is developing an OER program, connecting with others who are doing similar work will help you build a professional support system and sounding board for challenges that you might face.

As a project manager, you are typically the first point of contact for most team members and will be the de-facto expert for intricate questions on all kinds of topics. This means that, at the very least, you need to be well-versed in the basics of open education, licensing and copyright, publishing tools, and the OER landscape. You don’t need to be an expert on all these topics—in fact, one of the major skills of a project manager is knowing where to find answers and how to cultivate a good network so that you have the resources to answer such questions (Ashok and Wake Hyde, “Roles and Responsibilities,” 2019). A frequently requested topic, for example, is copyright and fair use. While you should have a basic understanding of both, connecting with your General Counsel or resident copyright or scholarly communications expert will make it easier to get the answers you need in a timely fashion.

Planning Successful Projects

Project managers often oversee multiple projects at once and work to prove the impact and value of OER initiatives at their institutions. The key to managing a successful OER project is planning. Taking your time at the start of each OER project to lay down the organizational foundation will make it easier for you to spend more time working with the team to implement the project components and make sure that things are progressing smoothly.

If you’re stepping into the role of project manager for the first time, start by identifying the communications and workflow management tools available online and via your institution. Familiarize yourself with the tools, and then begin setting up the organizational structure you need for each OER project. We also recommend that you take time to decide how and what services you can support and which you cannot. This will help prevent “scope creep” because you will have defined a set of options for your authors to choose from. You may not know what all you can offer if you are new to OER project management, so start small and scale up later. For example, you might not want to offer print-on-demand services right away (See Chapter 15, Making OER Available in Print).

Managing Expectations

A critical component of project management is managing expectations. Clarifying expectations (who is responsible for what task or part of the project, the goals, outputs, outcomes, and impact) will make it easier to keep the project organized and on track. Discuss the project’s scope and goals with faculty to create a common understanding. Consider what you want to achieve with each project and what is feasible. Fill out a project summary template or project roadmap and carefully think through key aspects, including the project’s license, audience, structure, and measures of success (Ashok and Wake Hyde, “Roles and Responsibilities,” 2019; Elder 2020).

When managing projects, you need to set the guidelines on how communication will happen, how work will be assigned, when parts of the project are due, and who is responsible for which aspects of the project. Ideally, these expectations are a part of your Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) or placed in a written document so that everyone is on the same page. Take a look at these templates and examples to reuse or adapt for your projects:

- Contributor MOU Template (Ashok and Wake Hyde, “Roles and Responsibilities,” 2019)

- Adaptable OER Publishing Agreement (Creative Commons USA, Open Education Network, and Rebus Community 2017)

- Service Level Agreement and Statement of Work Template (University System of Georgia 2021; Gallant 2020)

Get Acquainted with Your Tools

There are many free tools available if your budget is restricted, but these often have some limitations. When selecting a tool, think about the following:

- How many people need access? Who needs to see what stage the project is in and why?

- What data or information about a project do you need?

- How much can you afford?

- Are there any ethical considerations?

- What do you need the tool to do?

Then take an inventory of what is used on campus. You may have a selection of tools available to use, but you should limit your final choice to two or three. The more tools you use, the more complicated tracking your projects will be. However, you need to have enough tools to keep on track. The basics are a project management tool for each project, a communications tool, and a project overview tool. Let authors know which tools will be used. For example, if you prefer all communication go to your university email account, make that the standard.

Free trials are often a good way to start but don’t spend too much time reviewing every product. Choose the tools you need and stick to them. Take the time to learn them, be aware of their limitations, and make the most of the features available to you.

Tools Overview

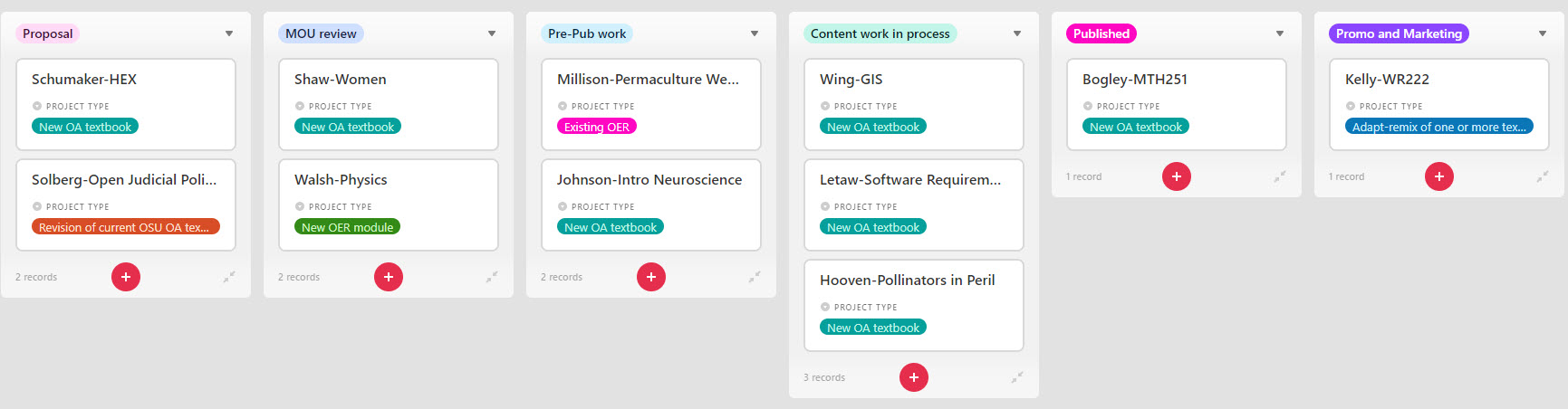

An overview tool is useful if you are managing around 10 or more projects at once. Different projects will have different milestones or stages and due dates, so an overview tool is something that gives you an “at a glance” overview of each project’s status and stage. This helps to keep everything moving forward even though each project may be at a different stage. These milestones or stages can be broad but with enough detail to tell you in which stage the project currently resides. This will help you prioritize what you need to work on next and/or which projects need more attention than others, depending on the stage they are in. Some examples of tools include:

Features to look for:

- Can you see multiple due dates on a timeline or calendar?

- Is there a way to sort projects by status, due date, or other milestones?

- Can you assign tasks to project team members?

- How does the tool integrate with others you are using (e.g., Outlook or Gmail)?

Use a comparison chart (e.g., Airtable vs. Asana vs. Trello) to evaluate the features, pricing, and value of different overview tools to see which one best suits your needs.

Specific Project Tools

For each project, you may want to have a separate project management planner so you can track the details of an individual project. If you do not have too many projects (e.g., less than 10), you may be able to just use the overview tool discussed above to meet this need. However, some projects may be more complex than others, with additional stages or milestones, and may need additional tracking to keep them on task. You can consider using the following:

- Google Sheets or Excel, with one sheet per project

- Example content tracking sheet (Hendricks and Rebus Community 2020)

- Trello

- Basecamp

You may also have additional guides or templates for each project to share with authors. Project-specific tools can help you organize and manage these resources.

Communications and File Management Tools

You will undoubtedly communicate a great deal with your authors/adaptors and other project team members. Keeping track of correspondence is critical. You should create one folder per project, no matter which system you are using. Outlook, Gmail, and Slack are all suitable communication tools, but we recommend that you choose one and stick with it. It’s tricky to follow a conversation that takes place across multiple tools. Ask your authors/adaptors to do the same.

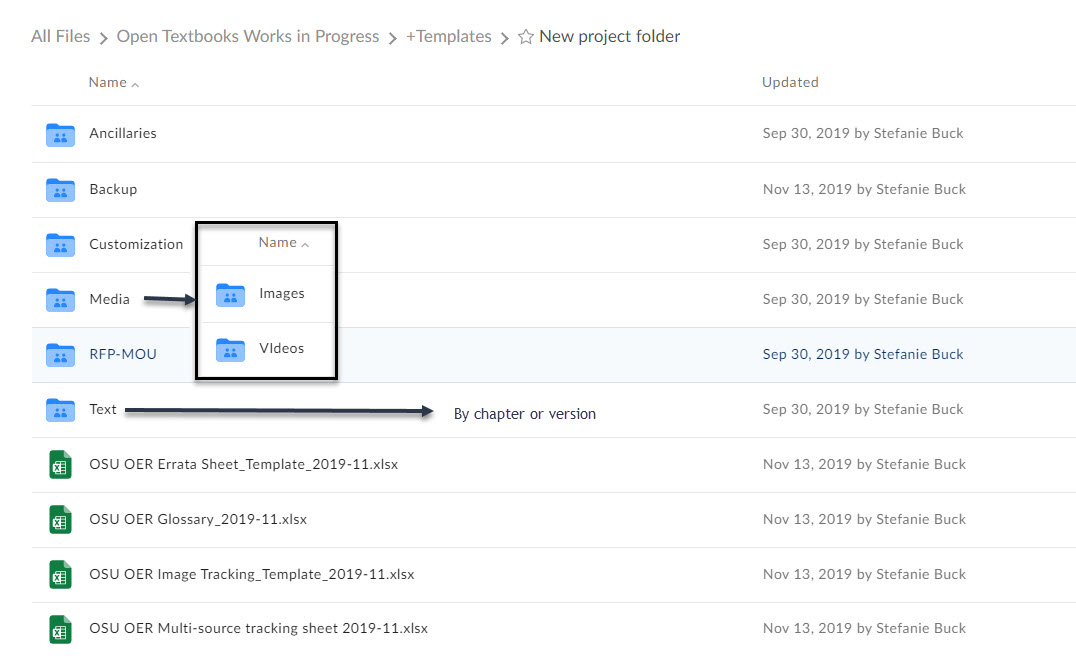

You will also have many shared files and documents for each project. These could include drafts, guidelines, agreements, templates, and media. You should supplement your tracking tools with a file management system. These may include the following:

Create one folder per project. You can break the content down into further subfolders. These folders are where all the documents related to a project must be hosted. Avoid emailing documents back and forth; it will be very hard to keep track of the document version if you do that. Ask your authors to make all changes in the master document in their project folder. Make sure you have ownership over all the folders and their contents; authors may leave the institution, so it is critical that you have access to the content.

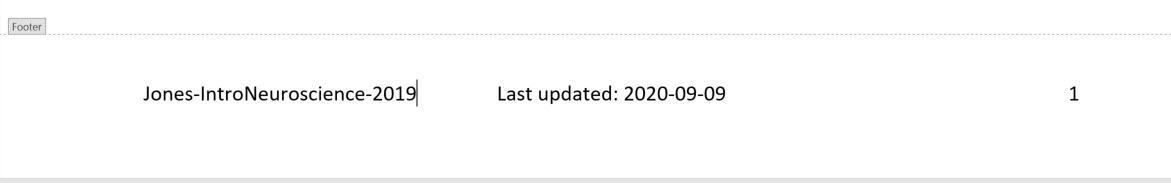

The naming convention for projects is very important so that your Box folders, Asana, Outlook, Gmail, etc. all match and so that all your team members are on the same page and you can easily find all the components of the project. Create a standard for how to name projects before you start working on any. Ensure that these are descriptive and allow you to differentiate between projects easily and that the folder will automatically sort in a way that is meaningful to you. For example, you might standardize file names as Author-Title-Date or Cohort-Title-Author. Use this format consistently and ask your authors to do the same.

- Example 1: Jones-IntroNeuroscience-2019

- Jones-IntroNeuroscince-2019-Text

- Jones-IntroNeuroscince-2019-Media

- Example 2: Cohort4-IntroNeuroscience-Jones

- Example 3: 2019-IntroNeuroscience_Jones

Every document should have a date when it was last updated. This is easy to do in Microsoft Office or Google Docs and will make life much easier when trying to find the latest version. Adding page numbers to all your documents and templates will make it easier to reference an exact page or section.

Figure out your work style and adapt accordingly. For example, with multiple overlapping projects, it may be easier to organize by project rather than by the date of project creation (See Figure 16.2 above).

What Data Do I Need to Track?

While this will vary across the board, it is helpful to keep track of basic project details, data around project progress, and data to report the impact of completed projects. Part 7 offers a deeper dive into data collection and reporting. Here, we’ll discuss some key fields and data points that may be good to consider when setting up your project management tools. Conduct an inventory of these fields, tailor them for your needs, and be attuned to them from the start of your project management role.

In general, it will be helpful for you to keep basic project information handy. This can include details such as:

- Project title

- Author details (contact information, department, campus, etc.)

- Project start and due dates

- Creative Commons license

- Funding (total amounts, disbursement schedule, business office details)

- Courses and term when the OER will be used (include type such as Gen. Ed., Honours, dual enrollment, and number of students enrolled)

- Publishing platform

Once projects are underway, tracking their progress will be essential. We have outlined some major milestones in the following list:

- Manuscript drafted

- Images and ancillaries created

- Drafts copyedited

- Review complete (accessibility review, peer review, student review, and other quality assurance)

- Formatting complete

- Communications plan created

- Project complete (it is a good idea to have a common understanding with your faculty author about what “complete” means)

- Communications plan implemented

Finally, after a project is completed, you should gather some data to evaluate and report the impact as the resource is being used. During this phase, you can also review your own workflows and identify areas of improvement for future projects. The following markers can be useful to report the efficacy and success of your project:

- Downloads of OER (disaggregated by format type, device, etc.)

- Page visits, shares, or views of the digital OER

- Adoption numbers (on your campus or around the world)

- Student savings generated or cost avoidance

- Changes in graduation rates, withdrawal rates, and drop rates

- Student feedback

- Instructor feedback

Your institution may provide other reporting requirements, so be sure to get a sense of what fields are necessary in order to set up your project tracking tool accordingly.

Timelines and Scheduling

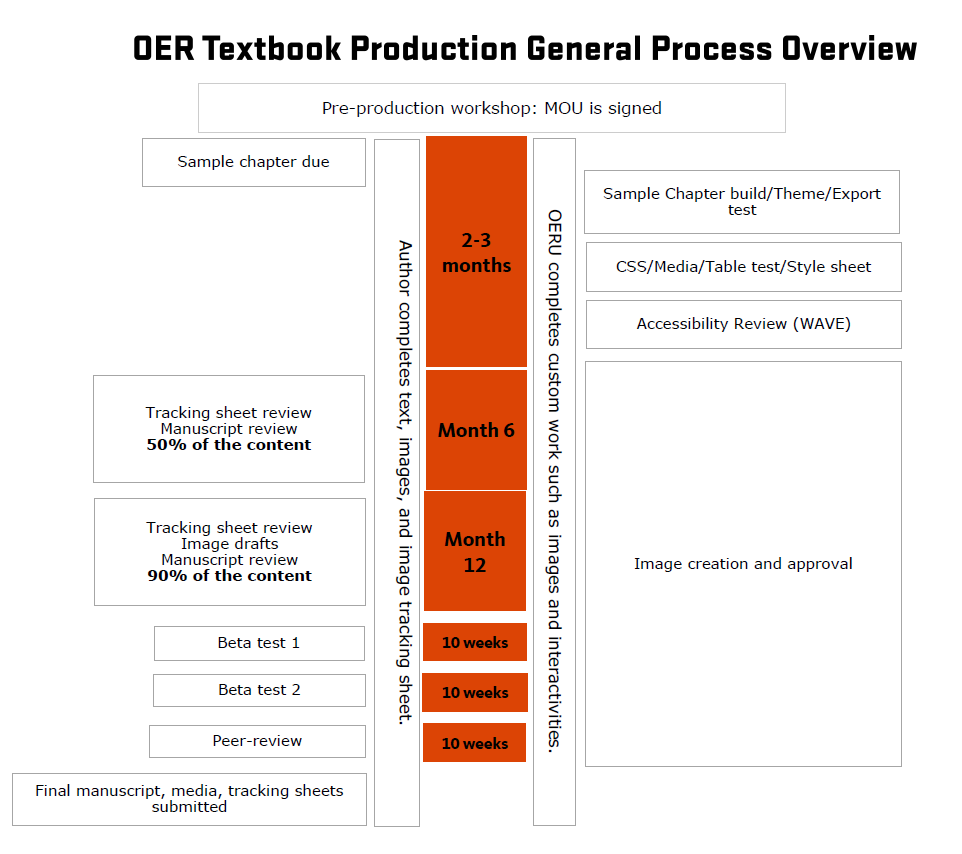

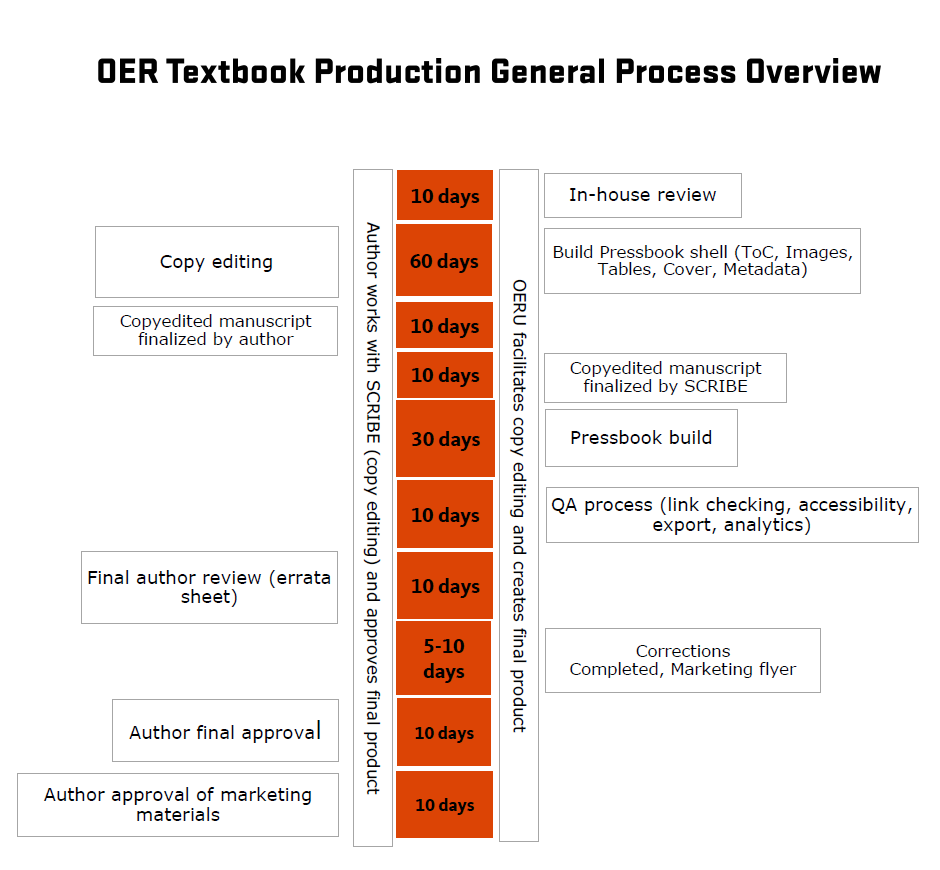

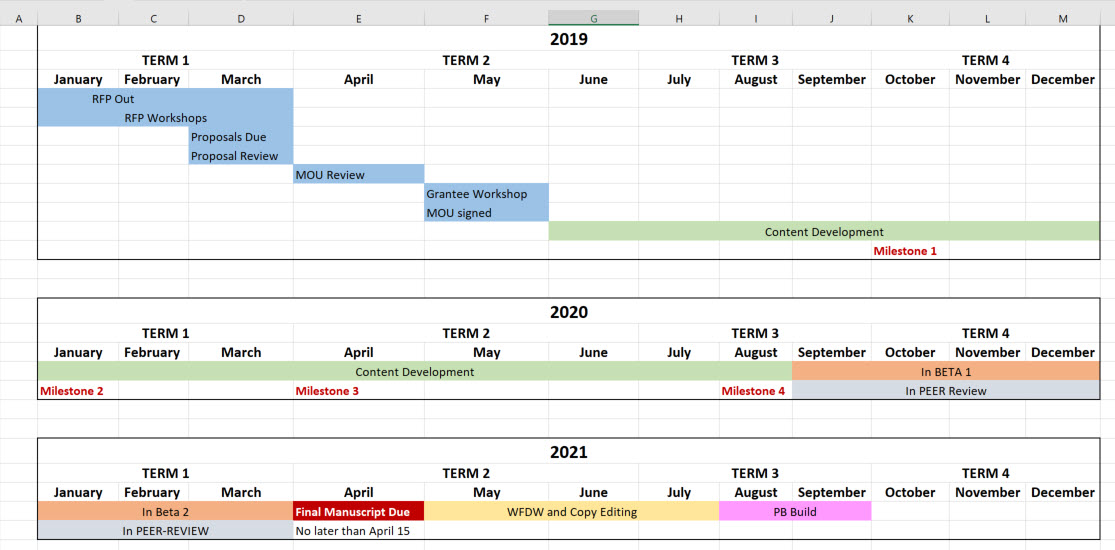

Be explicit about when things are due and what’s going to happen. Finishing the manuscript is a milestone, but implementing the OER is the larger goal. Give yourself some cushion when setting due dates so you have time to work with authors to transform their manuscript into a fully usable OER. With the final date for implementation in mind, work backward to set the deadlines.

Give your authors a simple breakdown of the timeline, as it pertains to their deliverables. However, make sure you continuously reference a more detailed timeline that captures all the moving parts. By giving your authors an overview of specific due dates relevant to them, they can stay focused on their tasks. Reminders around due dates for milestones should also be simple, and will come in very handy as authors are often juggling multiple projects at once. You can always rely on your project management tools to assist with setting reminders to help your authors and team stay on track to meet these deadlines.

To manage an individual project and keep it on time and task, you will want something more specific and detailed. For example, you will want to map out each individual project timeline as each project is unique. You can use something like Excel to create a Gantt style chart to help you visualize the timeline.

For a new textbook creation project, you may want to calculate a timeline of around 18 to 24 months. The timeline can vary based on the complexity of your project. As project manager, you will need to make sure the project is completed in a timely fashion. As described earlier, you can use the date when the author wants to use the OER in a course as the final due date, and calculate backward from here to estimate other deadlines. For example, if the author wants to use the OER in the fall term, then you may want to have the manuscript due 4 to 6 months in advance to give you the time to complete steps like copyediting, review, formatting, and final checks.

Some deadlines can be more flexible while others need to be hard deadlines. You want to give yourself some leeway if the author needs to push the deadline back by a week or two, but in some cases, the deadline needs to be firm. If possible, this should be part of your MOU. If you do not have an MOU, work with the author to establish deadlines via a mutually understood and agreed-upon project timeline. Make sure the author understands that if they miss the hard deadlines, you may not be able to guarantee that the OER will be ready by the original due date or that any funding contingent on these deliverables will be released in a timely way.

Overseeing Multiple Projects

Managing multiple projects is exponentially trickier than managing one or a few. Your projects will be at different stages, following different timelines, and will likely not be moving at the same pace. Juggling demands across projects can be overwhelming for both first-time and experienced project managers. This is when your preparation comes in handy. Maintain your project management tools so you can refer to them at critical points. Set aside some time in your workflow (be it a few minutes a day or week) to fill them in and ensure they are up to date. It’s important to build this into your work schedule. The most elaborate setup is useless if not properly maintained. Any setup is only as good as your investment in it, and your future self will thank you for it.

For those managing grants or who have a grant budget, it’s important to keep up to date with your funds. You need to make some decisions about when you will pay out the funds. Where should you spend your money (e.g., copyediting, contributing authors)? How much will you set aside for each?

Let’s say you have a budget of $5,000 for your project with two contributing authors:

| Task | % of $5,000 | Cost |

| Copyediting | 20% | $1,000 |

| Contributing authors | 20% x 2 | $2,000 |

| Formatting | 20% | $1,000 |

| Review honorarium | 10% | $500 |

| Contingency (emergency funds) | 10% | $500 |

Set aside a bit for emergencies. For example, copyediting is something you can usually estimate based on word count. But if the work needs heavier copyediting than anticipated, you’ll have a little set-aside. By setting your budget early, you’ll have a clear sense of the project costs (including contributor honorariums) and how funding will be distributed. As the budget owner, you should review the budget regularly until the project is complete.

- You’re in charge. As project manager, you negotiate with faculty members to plan out the project. People appreciate flexibility while being told up front what is needed. You might receive many requests over the course of the project, so carefully consider these and remember that, ultimately, you are the decision maker. Don’t be afraid to call the shots and say “no” to certain requests to keep your project on track. Be clear about the resources and capacity you have, things you can’t do or that are outside the project scope, and look for manageable alternatives.

- Get organized. Keep running notes on each project and review them before you meet with authors. With multiple projects at different stages, it is easy to lose your place (Walz 2020). Notes will refresh your memory!

- Each project is different. Share your project tracking sheet or dashboard with authors so they can monitor progress. Find ways to highlight priority items, indicate who is working on what, leave comments and questions, and generally identify what is done and what is left to do. Be prepared to tweak the dashboard to fit the project (Walz 2020).

- Communicate regularly. Work with each project’s lead author to identify a meeting frequency that is helpful to them. This will vary depending on the project stage. Use this time to listen to their progress reports and questions; celebrate achievements; update goals; encourage their progress; reassess needs; discuss issues and possible solutions; and discuss important upcoming decisions, milestones, or deadlines. This will help you keep the project moving even if something goes wrong (Walz 2020).

- Set expectations and timelines. With your author(s) and other members of your team, establish a timeline for each project. Be clear about roles, expectations, schedules, and deadlines. You can discuss overlapping schedules and thus help plan your (and others’) workload. Also, know and remind your team that timelines change, and that’s okay (Walz 2020).

- Projects are more than a number. Projects can start to blur together when you are managing multiple ones. However, for the faculty member involved in only one project, their project carries the most weight. Projects can be a lifelong dream for contributors, so try to treat each one with the care and attention that you would give your first.

- Process the emotional labour. Managing multiple projects and people while giving all the due diligence they warrant can be overwhelming. It’s okay to feel out of your depth at times. Know that you’re not alone and that your gut instincts will often lead you down the right path. Trust yourself and lean on your support team as often as you need.

Conclusion

Your primary goal as project manager is to see projects through to publication. Since collaborating with others is an essential part of this process, a successful project manager balances tasks and deadlines with empathy and understanding. You should make sure teams enjoy the work of creating and publishing OER. Sometimes this will involve offering extensions when life gets in the way. Be kind and willing to renegotiate deadlines as situations demand. This will help make sure that your collaborators can contribute without compromising their mental or physical health. Remember that you will be viewed as an example and that your behaviour on projects models your expectations for the team. So heed your own advice and know that it’s okay to step away from project work if you need a break. Your planning will ensure the projects run smoothly even during a brief hiatus.

Coordinating on a successful and engaged project can be one of the most fulfilling aspects of being a project manager. Even the pride of producing a large number of OER does not compare to the joy of the individual relationships you build with your team members, as this is what will be remembered with fondness later on. Moreover, yours is a unique position that connects distant offices and departments to create an OER network on campus. These newly established connections will outlive the initial project work and form the basis to sustain future OER efforts at your institution.

Recommended Resources

- Project Summary Template (Ashok and Wake Hyde, “Project Summary Template,” 2019)

- OER Mini-Grant Project Roadmap Worksheet (Elder 2020)

- Comparison Chart (Capterra, n.d.)

- Example Content Tracking Sheet (Hendricks and Rebus Community 2020)

- Contributor MOU Template (Ashok and Wake Hyde, “Contributor MOU template,” 2019)

- Adaptable OER Publishing Agreement (Creative Commons USA, Open Education Network, and Rebus Community 2017)

- Service Level Agreement and Statement of Work Template (University System of Georgia 2021; Gallant 2020)

- The project manager is the main point of contact for faculty or staff working on OER projects and the de facto expert for any related question. To manage this work, you should conduct an environmental scan of your institution and region’s work in OER, and cultivate a network that you can tap into for support.

- Work with faculty to create a shared understanding of the project, including its goals, timeline, budget allocations, and individual expectations. Revisit all of these regularly to stay on target.

- Review and select free or paid tools for tracking projects, file management, and communication. You may opt to use tools that are already part of your institution’s digital infrastructure, which will make it easier to collaborate with colleagues and track multiple projects.

- Think about what data to gather early on and build tracking into your project management workflow. Use this information in your regular reporting about the impact of OER.

- Being a project manager not only involves adapting workflows to suit projects’ needs and seeing them through to completion, but it also requires emotional labour to cultivate a motivated group of open practitioners. Treat your collaborators with respect and empathy, and they will do the same for you.

References

Ashok, Apurva and Zoe Wake Hyde. 2019. “Contributor MOU Template.” In The Rebus Guide to Publishing Open Textbooks (So Far), edited by David Szanto. Rebus Community. https://press.rebus.community/the-rebus-guide-to-publishing-open-textbooks/chapter/roles-responsibilities/

Ashok, Apurva and Zoe Wake Hyde. 2019. “Project Summary Template.” In The Rebus Guide to Publishing Open Textbooks (So Far). Rebus Community. https://press.rebus.community/the-rebus-guide-to-publishing-open-textbooks/chapter/project-summary-template/

Ashok, Apurva and Zoe Wake Hyde. 2019. “Roles & Responsibilities.” In The Rebus Guide to Publishing Open Textbooks (So Far). Rebus Community. https://press.rebus.community/the-rebus-guide-to-publishing-open-textbooks/chapter/roles-responsibilities/

Capterra. n.d. “Comparing 3 Collaboration Software Products.” Accessed February 14, 2022. https://www.capterra.com/collaboration-software/compare/146652-120550-72069/Airtable-vs-Asana-vs-Trello

Creative Commons USA, Open Education Network, and Rebus Community. 2017. “Adaptable Open Educational Resources Publishing Agreement.” Accessed March 14, 2021. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1HHf0GKoSLlNt1IgFurRwZxLiPfoI9NAE16VynhUpXmA/edit

Elder, Abbey. 2020. “OER Mini-Grant Project Roadmap Worksheet.” Accessed March 12, 2021. https://www.google.com/url?q=https://drive.google.com/drive/u/1/folders/1_ASpZImatERw8nrSrPIYEmcf7G6UgL-N&sa=D&ust=1600301164647000&usg=AFQjCNF_CmINJwc6gqJHIyKrAFQwuQYUew

Gallant, Jeff. 2020. “Statement of Work Template.” In Service Level Agreement. University System of Georgia. Accessed March 12, 2021. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1upxOUZJspMnUBP_aCYXxovNibmLRdSRo/view?usp=sharing

Hendricks, Christina, and Rebus Community. 2020. “Example Content Tracking Sheet.” Google Sheets. Accessed June 7, 2021. https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1rZgU_KMjnIAhHHoe_lYNKvC0HJg1y5Uy2F6J80GooSg/edit#gid=121348099

Langille, Donna. 2019. Rebus Community Reports: Insights from OER Project Leads. Montreal, Quebec: Rebus Foundation. https://press.rebus.community/rebuscommunityreports/.

University System of Georgia. 2021. “Service Level Agreement.” Accessed March 12, 2021. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1upxOUZJspMnUBP_aCYXxovNibmLRdSRo/view?usp=sharing.

Walz, Anita. 2020, September 22. “Lessons Learned from a Manager of Multiple Projects.” Email to authors.

Watt, Adrienne. 2014. Project Management-2nd Edition. BCCampus. https://opentextbc.ca/projectmanagement/