Exercise Solutions

Chapter One

First, explicate the following arguments, paraphrasing as necessary and only including tacit premises when explicitly instructed to do so. Next, diagram the arguments.

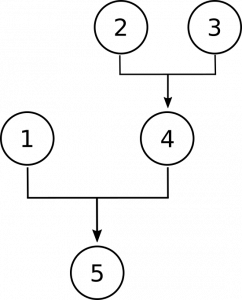

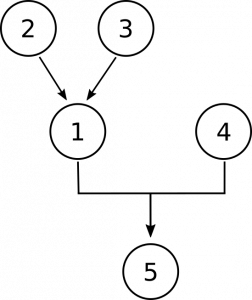

1. Numbers, if they exist at all, must be either concrete or abstract objects. Concrete objects—like planets and people—are able to interact with other things in cause-and-effect relations. Numbers lack this ability. Therefore, numbers are abstract objects. [You will need to add an implicit intermediate premise here!]

- Numbers must be either concrete or abstract objects.

- Concrete objects are able to interact with other objects in cause-and-effect relations.

- Numbers do not interact with other objects in cause-and-effect relations.

- Numbers are not concrete objects. [Implicit intermediate premise]

- [latex]/\therefore[/latex] Numbers are abstract objects.

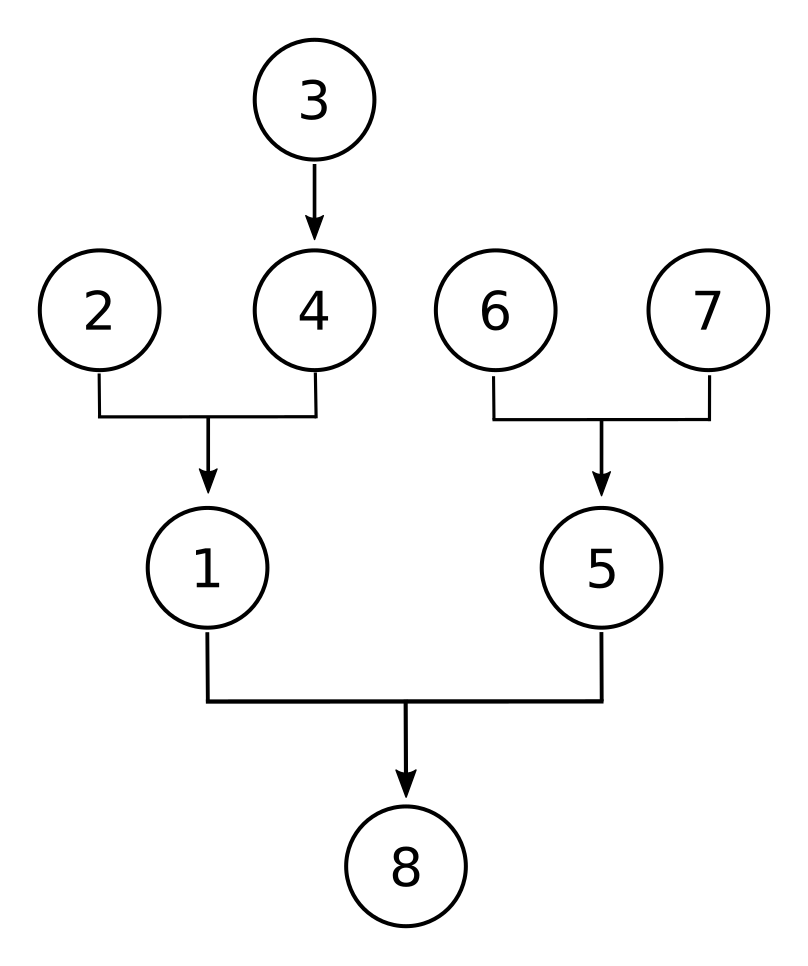

2. Abolish the death penalty! Why? It is immoral. Numerous studies have shown that there is racial bias in its application. The rise of DNA testing has exonerated scores of inmates on death row; who knows how many innocent people have been killed in the past? The death penalty is also impractical. Revenge is counterproductive: “An eye for an eye leaves the whole world blind,” as Gandhi said. Moreover, the costs of litigating death penalty cases, with their endless appeals, are enormous.

- The death penalty is immoral.

- Studies show that there is a racial bias in the application of the death penalty.

- DNA testing how exonerated scores of inmates on death row.

- Innocent inmates have been subject to the death penalty

- The death penalty is impractical.

- Revenge is counterproductive.

- The costs of litigating death penalty cases are enormous.

- [latex]/\therefore[/latex] The death penalty ought to be abolished.

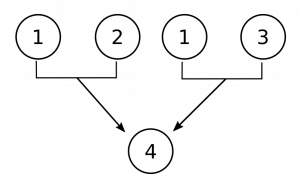

3. A just economic system would feature an equitable distribution of resources and an absence of exploitation. Capitalism is an unjust economic system. Under capitalism, the typical distribution of wealth is highly skewed in favor of the rich. And workers are exploited: despite their essential role in producing goods for the market, most of the profits from the sales of those goods go to the owners of firms, not their workers.

- Just economic systems feature an equitable distribution of resources and an absence of exploitation.

- Within capitalist systems, the typical distribution of wealth is highly skewed in favor of the rich.

- Within capitalist systems, workers are exploited.

- [latex]/\therefore[/latex] Capitalism is an unjust economic system.

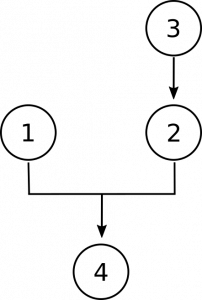

4. The mind and the brain are not identical. How can things be identical if they have different properties? There is a property that the mind and brain do not share: the brain is divisible, but the mind is not. Like all material things, the brain can be divided into parts—different halves, regions, neurons, etc. But the mind is a unity. It is my thinking essence, in which I can discern no separate parts.

- Identical objects must have the same properties.

- The mind and the brain do not have the same properties.

- The brain is divisible, whereas the mind is not.

- [latex]/\therefore[/latex] The mind and the brain are not identical.

5. Every able-bodied adult ought to participate in the workforce. The more people working, the greater the nation’s wealth, which benefits everyone economically. In addition, there is no replacement for the dignity workers find on the job. The government should therefore issue tax credits to encourage people to enter the workforce. [Include in your explication a tacit premise, not explicitly stated in the passage, but necessary to support the conclusion.]

- Every able-bodied adult ought to participate in the workforce.

- The more people working, the greater the nation’s wealth.

- Working provides irreplaceable dignity to individuals.

- Some individuals will not be able to work without tax credits. [Implicit intermediate premise]

- [latex]/\therefore[/latex] The government should issue tax credits to encourage people to work.

Chapter Two

Exercise One

For each argument decide whether it is deductive, inductive, or abductive. If it contains more than one type of inference, indicate which.

1.

- Chickens from my farm have gone missing.

- My farm is in the British countryside.

- [latex]/\therefore[/latex] There are foxes killing my chickens.

This is an abductive argument because it is attempting to explain some known phenomena, namely the chickens’ going missing, by inferring a hypothesis from all the information the individual has available to them: that the foxes killed the chickens.

2.

- All flamingos are pink birds.

- All flamingos are fire breathing creatures.

- [latex]/\therefore[/latex] Some pink birds are fire breathing creatures.

This is a deductive argument because it is attempting to demonstrate that it’s impossible for the conclusion “Some pink birds are fire breathing creatures” from the premises “All flamingos are pink birds” and “All flamingos are fire breathing creatures.”

3.

- Every Friday so far this year the cafeteria has served fish and chips.

- If the cafeteria is serving fish and chips and I want fish and chips then I should bring in £4.

- If the cafeteria isn’t serving fish and chips then I shouldn’t bring in £4.

- I always want fish and chips.

- [latex]/\therefore[/latex] I should bring in £4 next Friday.

This argument has both inductive and deductive components. To deductively infer that I should bring in £4 next Friday, in conjunction with the second and fourth premises, we need to know that every Friday the cafeteria serves fish and chips. However, at present we don’t know this. We only know that every Friday so far this year the cafeteria has served fish and chips. So, we need to make an inductive inference (i.e. an inference from observed instances to as of yet unobserved instances) from the first premise before we can deduce the conclusion using the other premises. So, made fully explicit the argument would look like this:

- Every Friday so far this year the cafeteria has served fish and chips.

- The cafeteria serves fish and chips every Friday (from first premise by induction).

- If the cafeteria is serving fish and chips and I want fish and chips then I should bring in £4.

- If the cafeteria isn’t serving fish and chips then I shouldn’t bring in £4.

- I always want fish and chips.

- [latex]/\therefore[/latex] I should bring in £4 next Friday.

Note that premise three isn’t actually needed in the argument, but this isn’t a problem. Lots of arguments have superfluous content.

4.

- If Bob Dylan or Italo Calvino were awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, then the choices made by the Swedish Academy would be respectable.

- The choices made by the Swedish Academy are not respectable.

- [latex]/\therefore[/latex] Neither Bob Dylan nor Italo Calvino have been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

This is also a deductive argument, as it’s attempting to demonstrate that it’s impossible for the conclusion to be false if the premises are both true. It’s also a valid argument, and is of the form:

- If A then B

- Not B

- [latex]/\therefore[/latex] Not A

which is known as Modus Tollens.

5.

- In all the games that the Boston Red Sox have played so far this season they have been better than their opposition.

- If a team plays better than their opposition in all their games then they will win the World Series.

- [latex]/\therefore[/latex] The Boston Red Sox will win the league.

This argument has both inductive and deductive components. To use premise 2 to deductively infer the conclusion requires us to know that the Boston Red Sox have played better than all of their opponents, yet this isn’t what premise one tells us. So to derive the claim that “The Boston Red Sox will play better than all of their opponents this year” we need to make an inductive inference from premise one (i.e. an inference from observed instances to as of yet unobserved instances). So, made fully explicit the argument would look like this:

- In all the games that the Boston Red Sox have played so far this season they have been better than their opposition.

- The Boston Red Sox will be better than all their opposition this year (from first premise by induction)

- If a team plays better than their opposition in all their games then they will win the World Series.

- [latex]/\therefore[/latex] The Boston Red Sox will win the league.

6.

- There are lights on in the front room and there are noises coming from upstairs.

- If there are noises coming from upstairs then Emma is in the house.

- [latex]/\therefore[/latex] Emma is in the house

This is a deductive argument, as it’s attempting to demonstrate that it’s impossible for the conclusion to be false if the premises are both true. It’s also a valid argument, and is of the form:

- A and B

- If B then C

- [latex]/\therefore[/latex] C

This form of argument is known as Modus Ponens.

Exercise Two

Give examples of arguments that have each of the following properties:

1. Sound

Here you want to provide an argument which is valid and which has actually true premises. Here is an example:

- All mammals are animals

- Bears are mammals

- [latex]/\therefore[/latex] Bears are animals

2. Valid, and has at least one false premise and a false conclusion

Here you need to provide an argument whose conclusion must be true if all the premises are true, but that actually at least one of the premises is false and the conclusion is false. Here’s an example:

- All fish are mammals

- Piranhas are fish

- [latex]/\therefore[/latex] Piranhas are mammals

3. Valid, and has at least one false premise and a true conclusion

Here you need to provide an argument whose conclusion must be true if all the premises are true, but that actually at least one of the premises is false and the conclusion is true. Here’s an example:

- All birds can fly

- Seagulls are birds

- [latex]/\therefore[/latex] Seagulls can fly

4. Invalid, and has at least one false premise and a false conclusion

Here you need to provide an argument whose conclusion can be false even if all the premises are true, and also that actually at least one of the premises and the conclusion is false. Here’s an example:

- All birds can fly

- Seagulls are birds

- [latex]/\therefore[/latex] Piranhas can fly

5. Invalid, and has at least one false premise and a true conclusion

Here you need to provide an argument whose conclusion can be false even if all the premises are true, and also that actually at least one of the premises is false but the conclusion is true. Here’s an example:

- All birds can fly

- Seagulls are birds

- [latex]/\therefore[/latex] Piranhas can swim

6. Invalid, and has true premises and a true conclusion

Here you need to provide an argument whose conclusion can be false even if all the premises are true, and also that actually the premises and the conclusion are true. Here’s an example:

- All mammals are animals

- Bears are mammals

- [latex]/\therefore[/latex] Piranhas can swim

7. Invalid, and has true premises and a false conclusion

Here you need to provide an argument whose conclusion can be false even if all the premises are true, and also that actually the premises are true but the conclusion is false. Here’s an example:

- All mammals are animals

- Bears are mammals

- [latex]/\therefore[/latex] Piranhas can fly

8. Strong, but invalid [Hint: Think about inductive arguments.]

Here you need to provide a strong argument, that is an argument whose premises support its conclusion, which isn’t deductively valid. The easiest way to do this is to provide an inductively strong argument:

- The Sun has risen every day for the past two-thousand years

- [latex]/\therefore[/latex] The Sun will rise tomorrow

Chapter Three

Exercise One

Using a truth-table, show that the following argument, which is known as the fallacy of affirming the consequent, is invalid: [latex]A \rightarrow B[/latex], [latex]B[/latex]; [latex]/\therefore A[/latex].

| [latex]A[/latex] |

[latex]B[/latex] | [latex]A \rightarrow B[/latex] | [latex]B[/latex] | [latex]A[/latex] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | T | T | T |

| T | F | F | F | T |

| F | T | T | T | F |

| F | F | T | F | F |

The truth-table above shows that the argument is invalid, because there is one circumstance in which both premises are true and the conclusion is false (provided by the third row of the truth-table).

Exercise Two

Using a truth-table, how that the following argument, which is known as the hypothetical syllogism, is valid: [latex]A \rightarrow B[/latex], [latex]B \rightarrow C[/latex]; [latex]/\therefore A \rightarrow C[/latex]. [Hint: Your truth-table should have eight rows, as there are three propositional variables—A, B, and C—that you need to include within it.]

| [latex]A[/latex] | [latex]B[/latex] | [latex]C[/latex] | [latex]A \rightarrow B[/latex] | [latex]B \rightarrow C[/latex] | [latex]A \rightarrow C[/latex] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | T | T | T | T |

| T | T | F | T | F | F |

| T | F | T | F | T | T |

| T | F | F | F | T | F |

| F | T | T | T | T | T |

| F | T | F | T | F | T |

| F | F | T | T | T | T |

| F | F | F | T | T | T |

The truth-table above shows that the argument is valid, as there no circumstances (rows in the truth-table) in which both premises are true and the conclusion is false.

Exercise Three

Evaluate whether the following arguments are valid or invalid. First, identify their logical form, and then use truth-tables to establish their (in)validity.

1. We now know the situation. The Yankees either have to beat the Red Sox or they won’t make it to the World Series, and they won’t do the former.

- The Yankees have to beat the Red Sox or the Yankees won’t make it to the World Series

- The Yankees won’t beat the Red Sox

- [latex]/\therefore[/latex] The Yankees won’t make it to the World Series

A = The Yankees have to beat the Red Sox

B = The Yankees will make it to the World Series

- [latex]A \vee \neg B[/latex]

- [latex]\neg A[/latex]

- [latex]/\therefore \neg B[/latex]

| [latex]A[/latex] | [latex]B[/latex] | [latex]A \vee \neg B[/latex] | [latex]\neg A[/latex] | [latex]\neg B[/latex] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | T | F | F |

| T | F | T | F | T |

| F | T | F | T | F |

| F | F | T | T | T |

The truth-table above shows that the argument is valid, as the only circumstance in which both premises are true (row four of the truth-table) is also a circumstance in which the conclusion is true. This form of argument is known as the disjunctive syllogism.

2. Sarah will only pass the discrete mathematics exam if she knows her set theory. Fortunately, she does know set theory well, so she will pass the exam.

- If Sarah passes her discrete mathematics exam then she knows set theory

- Sarah knows set theory

- [latex]/\therefore[/latex] Sarah will pass her discrete mathematics exam

A = Sarah will pass her discrete mathematics exam

B = Sarah knows set theory

- [latex]A \rightarrow B[/latex]

- [latex]B[/latex]

- [latex]/\therefore A[/latex]

| [latex]A[/latex] | [latex]B[/latex] | [latex]A \rightarrow B[/latex] | [latex]B[/latex] | [latex]A[/latex] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | T | T | T |

| T | F | F | F | T |

| F | T | T | T | F |

| F | F | T | F | F |

The truth-table above shows that the argument is invalid, because there is a circumstance in which both premises are true and the conclusion is false (provided by the third row of the truth-table). This is another instance of the formal fallacy known as asserting the consequent.

3. It just isn’t the case that you can be a liberal and a Republican, so either you’re not a Republican or you’re not a liberal.

- One cannot be both a liberal and a Republican

- [latex]/\therefore[/latex] Either you’re not a Republican or you’re not a liberal

A = You are a liberal

B = You are a Republican

- [latex]\neg (A \wedge B)[/latex]

- [latex]/\therefore \neg B \vee \neg A[/latex]

| [latex]A[/latex] | [latex]B[/latex] | [latex]\neg (A \wedge B)[/latex] | [latex]\neg B \vee \neg A[/latex] |

|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | F | F |

| T | F | T | T |

| F | T | T | T |

| F | F | T | T |

The truth-table above shows that the argument is valid, as every circumstance in which the premise is true is also one in which the conclusion is true. This argument is an instance of one of the DeMorgan laws, which states propositions of the form [latex]\neg (A \wedge B)[/latex] are equivalent to those of the form [latex]\neg A \vee \neg B[/latex]. How do you think we show the truth of this law? [Hint: We’ve already achieved one of the two required steps]

4. If Dylan goes to law or medical school then he’ll be OK financially. Fortunately, he’s going to law school.

- If Dylan goes to law school or Dylan goes to medical school he’ll be OK financially

- Dylan is going to law school

- [latex]/\therefore[/latex] Dylan will be OK financially

A = Dylan goes to law school

B = Dylan goes to medical school

C = Dylan will be OK financially

- [latex](A \vee B) \rightarrow C[/latex]

- [latex]A[/latex]

- [latex]/\therefore C[/latex]

| [latex]A[/latex] | [latex]B[/latex] | [latex]C[/latex] | [latex](A \vee B) \rightarrow C[/latex] | [latex]A[/latex] | [latex]C[/latex] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | T | T | T | T |

| T | T | F | F | T | F |

| T | F | T | T | T | T |

| T | F | F | F | T | F |

| F | T | T | T | F | T |

| F | T | F | F | F | F |

| F | F | T | T | F | T |

| F | F | F | T | F | F |

The truth-table above shows that the argument is valid, as in the only two circumstances in which both premises are true (the first and third rows of the truth-table) the conclusion is also true. This argument is an instance of asserting the antecedent, otherwise known as modus ponens, but in which the antecedent is a disjunction rather than a singular proposition.

Chapter Four

Exercise One

For each statement identify the informal fallacy.

1. It’s not wrong for newspapers to pass on rumours about sex scandals. Newspapers have a duty to print stories that are in the public interest, and the public clearly have a great interest in rumours about sex scandals since when newspapers print such stories, their circulation increases.

This argument deals on an equivocation of the meaning of “public interest.”

The argument might seem plausible because in the first instance of “public interest,” this means “in the public good,” but in the second instance, “great interest” just means, “the public find it interesting.” Given that in the public good and the public find it interesting don’t mean the same thing, the argument rests on an equivocation.

2. Free trade will be good for this country. The reason is patently clear. Isn’t it obvious that unrestricted commercial relations will bestow on all sections of this nation the benefits which result when there is an unimpeded flow of goods between countries?

This argument begs the question, for it simply presupposes that free trade will be good for the country by restating the conclusion in more complicated terms.

3. Of course the party in power is opposed to shorter terms, that’s just because they want to stay in power longer.

This is an ad hominem argument, in that it attempts to undermine the argument (or opinion) of the political party purely in virtue of their motivations, and not by actively engaging with the argument.

4. A student of mine told me that I am her favorite professor, and I know that she’s telling the truth, because no student would lie to her favorite professor.

This argument begs the question. The argument concludes that a student believes that the professor is her favorite, but relies upon this very fact in appealing to “no student would lie to her favorite professor” to establish the conclusion.

5. Anyone who tries to violate a law, even if the attempt fails, should be punished. People who try to fly are trying to violate the law of gravity, so they should be punished.

This argument deals on an equivocation of the meaning of “law.” In the first instance, in “violate a law,” we are meant to interpret this as “legal law,” whereas in the second instance, “people who try to fly are trying to violate the law of gravity,” what is obviously meant is a law of nature, and not a legal law.

6. There are more Buddhists than followers of any other religion, so there must be some truth to Buddhism.

This is a simple appeal to popularity.

Chapter Five

Exercise One

For each pair, decide whether the first member of the pair is either a necessary condition for the second, a sufficient condition, or neither.

1.

Bob drew the eight of Spades from an ordinary deck of playing cards.

Bob drew a black card from a deck of ordinary playing cards.

As Spades cards are black, but not the only black cards, Bob drawing a Spade is sufficient but not necessary for him to draw a black card.

2.

Alice has a brother-in-law.

Alice is not an only child.

Alice’s having a brother-in-law is neither sufficient nor necessary for Alice’s not being an only child. It fails to be sufficient because Alice could have a brother-in-law in virtue of her spouse having a brother. Additionally, Alice could have a sibling who is not married to a man. Thus, Alice’s having a brother-in-law is not necessary for her failing to be an only child.

3.

Alice’s daughter is married.

Alice is a parent.

Alice’s daughter being married is sufficient for Alice to be a parent, as it ensures its truth. However, it isn’t necessary for her being a parent. She could, for example, have only sons, or unmarried daughters.

4.

Alice’s daughter is married.

Alice is a grandmother.

Alice’s daughter being married is neither necessary nor sufficient for Alice being a grandmother. It fails to be necessary because Alice could be a grandmother with only sons, or with daughters who are unmarried. It fails to be sufficient because Alice’s daughter could be married without children.

5.

Some women pay taxes.

Some taxpayers are women.

Some women paying taxes is both necessary and sufficient for some taxpayers being women, as the two claims are synonymous.

6.

All women pay taxes.

All taxpayers are women.

All women paying taxes is neither necessary nor sufficient for all taxpayers being women. It fails to be necessary because it may be that while only some women pay taxes, no non-women do, and it fails to be sufficient because even if all women pay taxes, some non-women may also pay taxes.

7.

Being a mammal

Being warm blooded

Being a mammal is sufficient for being warm-blooded, as being mammal ensures being warm blooded. However, it fails to be necessary, as one can be warm blooded and a non-mammal, such as a bird.

8.

Being warm blooded

Being a mammal

Being warm blooded is necessary for being a mammal, as being mammal requires being warm blooded. However, it fails to be sufficient, as in addition to being warm blooded one must also possess certain other characteristics, such as possessing hair and giving birth to live young.

Exercise Two

For each claim, rewrite it in terms of necessary and/or sufficient conditions.

1. You must pay if you want to enter.

Payment is necessary for entrance.

2. A cloud chamber is needed to observe subatomic particles.

A cloud chamber is necessary to observe subatomic particles.

3. If something is an electron it is a charged particle.

Being an electron is sufficient for a charged particle.

4. Your car is only cool if it’s a Honda.

Your car’s being a Honda is necessary for its being cool.

5. Being a triangle just is being a three-sided two-dimensional shape.

Being a triangle is necessary and sufficient for being a three-sided two-dimensional shape.

An argument that aims to be valid.

An argument that moves from observed instances of a certain phenomenon to unobserved instances of the same phenomenon.

An argument that attempts to provide the best explanation possible of certain other phenomena as its conclusion. Also known as inference to the best explanation.

An argument in which it is impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion false.

An event or proposition which is required for another event to occur or proposition to be true. Conditionals express that the consequent is a necessary condition for the antecedent.

An event or proposition which ensures that another event occurs or another proposition is true. Conditionals express that the antecedent is a sufficient condition for the consequent.