8 Showing up and Standing with: An Intersectional Approach to a Participatory Evaluation of a Housing First Program

Anna S. Pruitt, Eva McKinsey, Tien Austin & John P. Barile

This case story describes the process of forming a five-year, ongoing participatory evaluation partnership between Housing First program participants, staff, and community psychologist evaluators in the multicultural context of the Island of O‘ahu in Hawai‘i.

The Big Picture

This chapter describes the process of forming a five-year, ongoing participatory evaluation partnership between Housing First program participants, staff, and community psychologist evaluators in the multicultural context of the Island of O‘ahu in Hawai‘i. Housing First is a community-based program that quickly provides permanent housing to individuals experiencing homelessness and emphasizes “consumer choice” in housing and service plans (Tsemberis, 2010). What started out as a top-down evaluation design conducted by traditional academic researchers became a weekly support group that engages in participatory research, often utilizing arts-based methods. Using an intersectional lens (Crenshaw, 1989; Weber, 2009), this case study explores the challenges and successes of building this partnership among individuals from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds with varying degrees of power, housing experiences, and mental and physical health issues. While many members of the partnership experienced challenges that typically deter traditional researchers from engaging in collaborative research, our partnership demonstrates many strengths, including valuable lived experience, resourcefulness, and critical insight that allowed for the creation of a space that is both supportive and conducive to rigorous participatory research and advocacy.

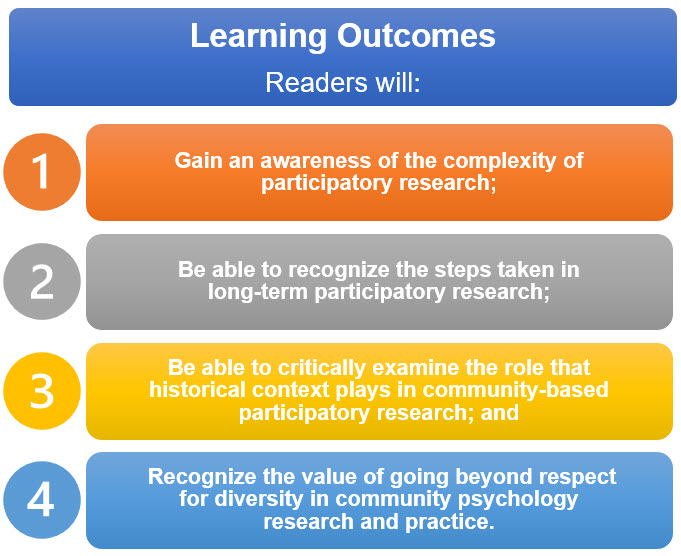

The main objectives of this case study are to demonstrate the application of community psychology values—particularly, respect for diversity, collaboration and participation, and historical context—in building research partnerships among individuals located at multiple axes of oppression. In particular, this case study demonstrates that respect for diversity is incomplete without attention to intersectionality and colonial trauma and argues for community psychology practice that is explicitly intersectional. Learning outcomes are shown below and include (1) gaining an awareness of the complexities of participatory research, (2) being able to recognize the steps taken in long-term participatory research, (3) critically examining the role that historical context plays in community-based participatory research, and (4) recognizing the value of going beyond respect for diversity in community psychology research and practice. The figure below highlights these learning outcomes:

Intersectionality as Critical Praxis

Intersectionality is a field of study, an analytical strategy, and a critical praxis that understands race, ethnicity, class, gender, sexuality, age, ability, and other salient social categories as interconnected, reciprocal phenomena that interact to influence complex social inequalities (Collins, 2015). Within an intersectional framework, these identity categories are not mutually exclusive but rather are socially constructed categories whose intersections manifest in experiences of oppression and privilege (Bilge, 2014; Collins, 2015). For example, an individual identifying as a white, heterosexual, low-income woman is privileged along lines of race and sexual orientation but potentially oppressed along lines of gender and class. Importantly, these identities are tied to systems of power that are embedded within specific geographic, social, political, and historical contexts that have implications for lived experiences (Weber, 2009). For example, a person living in the American South who identifies as a white woman will likely have different experiences than an individual identifying as a Black woman in the same context. And these experiences are likely to shift because identities—and different aspects of identities—have different meanings in different contexts. Indeed, a 20-year-old individual identifying as a Black woman in New York City has different experiences than an 80-year-old individual identifying as a Black woman in the rural American South. An intersectional approach challenges the notion that singular identities can explain lived experiences of oppression and directs attention to the interdependent and structural forces, processes, and practices that result in complex inequalities (Grzanka, 2020).

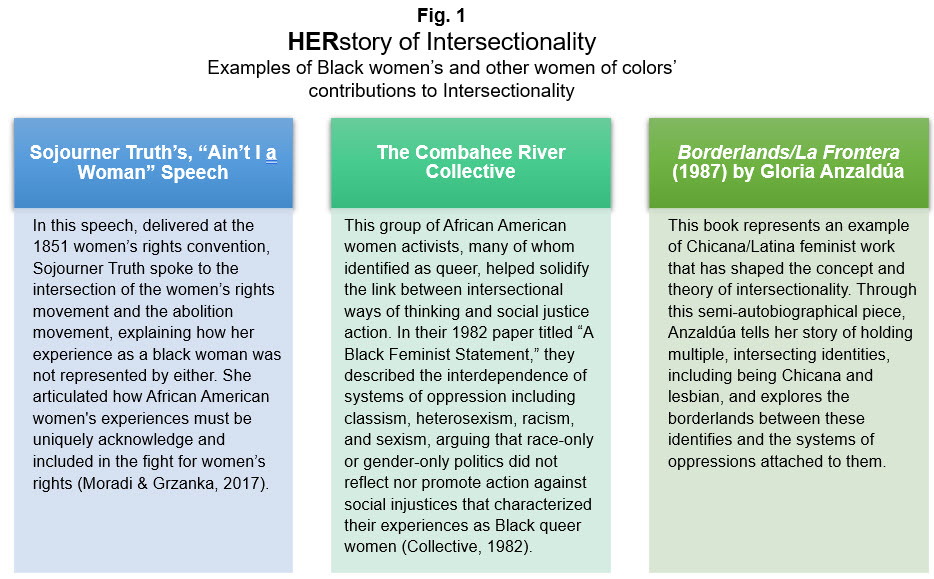

Grounded in Black feminism, the concept and field of intersectionality were created and shaped by African American women and other women of color scholars and activists. In fact, the HERstory of intersectionality traces back centuries, with prominent contributions from Sojourner Truth, the Combahee River Collective, and Gloria Anzaldúa (see Fig. 1). In the late 1980s, Kimberlé Crenshaw applied the framework to the legal realm and introduced the term “intersectionality” to describe the colliding systems of racism and sexism that Black women experience and that result in a unique form of oppression that single identity politics and legal protections had yet to address (Crenshaw, 1989; Crenshaw, 1991). For example, because Black women are discriminated against on the basis of race and gender, they often fall through the cracks in the legal system that implicitly assumes racism to affect Black men and sexism to affect White women.

Part of the ingenuity of this framework is that, despite its grounding in the experiences, scholarship, and activism of Black women and other women of color, it can be used in novel contexts and across diverse interpretive communities (Collins, 2015; Moradi & Grzanka, 2017).

While this chapter relies on all three of these conceptualizations at times, intersectionality’s conceptualization as a form of critical praxis is most relevant to this case study. Critical praxis refers to the merging of critical thinking and social and political activism, with the ultimate goal of transforming systems of oppression (Gramsci, 1971). As a form of critical praxis, intersectionality not only seeks to understand experiences resulting from interdependent identities and systems of oppression but also seeks to critique and change the systems we study in order to create more just systems (Collins, 2015; Grzanka, 2020). Through this conceptualization, authentic community engagement, social and political impact, and centering voices and stories of resistance becomes essential (Moradi & Grzanka, 2017). Indeed, this type of engagement and transformation were major goals of our evaluation partnership.

Intersectionality and Community Psychology

While community psychologists rarely refer to intersectionality explicitly in academic literature, the overlap between intersectionality and community psychology exists, and we (community psychologist evaluators) found that an intersectional approach was helpful in guiding our community psychology practice. From a theoretical standpoint, both intersectionality and community psychology emphasize the impacts of macro-level systems (e.g., policies, economic processes, etc.) on individuals and communities and the role of power in constructing lived experiences. Importantly, both recognize the interactions between macro-and micro-level processes, and both community psychology and intersectionality emphasize the importance of social action and the potential of a collective power to respond to the inequities created by oppressive systems of power. Additionally, community psychology’s focus on context is reminiscent of intersectional frameworks that highlight the interaction of individuals and their context and the fact that different identities and intersections are more or less salient in certain contexts (Weber, 2009). Community psychology has long argued that any community practice and research must begin with an understanding of the social and historical context. In fact, one of community psychology’s four guiding principles is that social problems are best understood by viewing people within their social, cultural, economic, geographic, and historical contexts (SCRA, 2020).

In addition to understanding others in context, community psychologists should engage in ethical and reflective practice—a key competency for community psychologist practitioners (SCRA, 2011). Thus, it is important for community psychologists not only to understand the context that impacts community partners but also to reflect and understand their place within it. Intersectionality also highlights the necessity of the examination of one’s own place within power structures (Weber, 2009). It is especially important for community psychologists to seek out such an understanding given our field’s stated values of respect for diversity and inclusion (SCRA, 2020). We cannot live up to these values without an understanding as to what makes our social experiences diverse. As we turn to the project of focus, consider the potential systems of power interacting and impacting the ongoing partnership and resulting research. We start with attention to historical and sociopolitical context.

Community Context

This partnership takes place on the Island of O‘ahu in Hawai‘i. O‘ahu, known as “The Gathering Place”, is home to almost a million people, with approximately 115,000 tourists visiting the island on any given day, pre-COVID-19 (Hawaii Tourism Authority, 2019a). Hawai‘i is one of the most diverse states in the United States, with no ethnic group holding a majority, and O‘ahu is the most diverse of the islands, with 43% of residents identifying as Asian, 23% identifying as multiracial, 10% Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and only 22% identifying as White only, compared to 76% nationwide (US Census Bureau, 2019). The state capital, Honolulu, as well as the internationally-known tourist hotspot, Waikīkī, are located on O‘ahu. Not surprisingly, tourism is the major economic engine of the state. In 2019, the state brought in over 17 billion dollars in tourism monies and enjoyed one of the lowest unemployment rates in the nation (Hawai‘i Tourism Authority, 2019b; US Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020b). However, tourism also drives up the cost of living and reduces the affordable housing stock. As expensive apartments and tourist lodgings replace affordable housing, rental rates and housing costs increase, and local residents are “priced out” (Moore, 2019). Indeed, Hawai‘i has both the highest cost of living and the lowest wages in the nation (after adjusting for said cost of living (HI Appleseed, 2019). Thus, despite its low rates of unemployment, Hawai‘i has high rates of poverty and homelessness.

Homelessness in Hawai‘i

Hawai‘i has one of the highest homelessness rates in the United States. In 2019, Hawai‘i had the 4th highest homelessness rate in the nation behind Washington D.C., Guam, and New York. Additionally, its homelessness rate has grown since 2007, while the overall national homelessness rate has fallen during this same time period as reported by the National Alliance to End Homelessness. On any given night, approximately, 6,458 individuals were experiencing homelessness in Hawai‘i in 2020 (State of Hawaii Homelessness Initiative, 2020). The majority—4,448 individuals—lived on O‘ahu (Partners in Care, 2020). Notably, the majority of these individuals (53%) were living unsheltered (e.g., in parks, on beaches), making homelessness highly visible (Partners in Care, 2020). Additionally, between July 1, 2018 and June 30, 2019, a total of 16,527 people received some form of housing services or assessment, suggesting that homelessness affects a significant number of people in Hawai‘i (Pruitt, 2019). Given the high visibility and its perceived impact on tourism, the “homelessness problem” is especially salient in local public policy and local media (Pruitt et al., 2020). Unfortunately, due to the economic fallout from the global pandemic, the homelessness rate is expected to increase, and 19,000 low-income people are projected to fall into poverty in the coming year (Hawai‘i Data Collaborative, 2020; Partners in Care, 2020).

Decades of research reveal that homelessness in the United States results from a lack of affordable housing, high rates of poverty, and social exclusion on the basis of certain individual characteristics (Shinn & Khadduri, 2020). While certain individual characteristics are associated with increased risk for homelessness (e.g., experiencing mental illness, being a member of an ethnic or racial minority), social exclusions (e.g., racist housing policies, such as “redlining”) actually “turn individual characteristics into vulnerabilities for homelessness” (Shinn & Khadduri, 2020, p. 52). Homelessness, in turn, exacerbates existing risk factors and can lead to further social exclusion and isolation from community support networks. From an intersectional perspective, individual characteristics interact to produce identities that are associated with different intersecting systems of power that lead to homelessness.

The local context of O‘ahu reflects these research findings. Honolulu’s high fair market rent rate is positively associated with its high homelessness rate (Barile & Pruitt, 2017). Importantly, not all residents are affected by poverty and homelessness equally. Despite prominent narratives that claim Hawai‘i is a “racial paradise,” stark inequalities exist related to race, class, and native ancestry. For example, Native Hawaiians are disproportionately represented in the island’s homeless population, comprising 43 percent of individuals experiencing homelessness, while representing only 19 percent of the general population on O‘ahu (OHA, 2019).

A recent racial equity report suggested that racial disparities may exist in housing services provisions as well (Pruitt, 2019). For example, Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders were less likely to receive permanent supportive housing compared to whites and Asians. Additionally, Native Hawaiians make up a larger percentage of the unsheltered than sheltered homeless (Pruitt & Barile, 2020). In Hawai‘i, large encampments of homeless communities are not uncommon, offering social support and a return to “kauhale” living. Disparities between social classes are prominent as well. Hawai‘i was rated second of all states with the highest rates of taxes on low-income households, further increasing inequities between the wealthiest and the poorest residents (Institute for Taxation and Economic Policy, 2018). Class intersects with race and ethnicity as non-white and non-Asian groups are more likely to live in poverty and rely on housing subsidies.

Colonial History

Homelessness in Hawai‘i cannot be understood without an understanding of Hawai‘i’s colonial history. Prior to Western contact, Hawaiians—Kānaka Maoli—lived in kauhale living systems, sharing sleeping and living spaces, often under the stars (Watson, 2010). Each island was divided into ahupuaʻa, wedged-shaped pieces of land that stretched from the mountains to the sea. These ahupuaʻa were ruled by local chiefs, and each ahupuaʻa was meant to be self-sustaining, ensuring that everyone, including commoners (makaʻāinana), had necessary resources from both the land and sea (Minerbi, 1999).

Private land ownership did not exist within a Native Hawaiian system. Native Hawaiian homelessness has been attributed, in part, to two major historical events: The Great Mahele and the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom by the United States. With the dispossession of land and the fragmentation of Hawaiian communities, came Western homelessness. Even after contact with Western nations, The Kingdom of Hawai‘i remained a sovereign nation until the end of the 19th century (Goodyear-Ka‘ōpua, 2014). However, foreign pressures led to changes to the Hawaiian way of life. In 1848, under pressure from foreign advisors, King Kamehameha III introduced the Great Māhele (division of land), marking the beginning of private land ownership in Hawai‘i. To be awarded newly privatized land, makaʻāinana were required to file a claim, provide testimony, pay for a survey of the land to be completed, and obtain a Royal Patent. Only around 30% of makaʻāinana achieved all steps and were awarded on average 3.3 acres. Thus, the Great Māhele displaced a sizable number of maka āinana from their ancestral lands (Stover, 1997).

The late 19th century saw further challenges to the Hawaiian way of life and the sovereignty of the monarchy. In 1887, the Hawaiian League, a group of mostly White American businessmen, forced a new constitution upon King Kalākaua at gunpoint. This “Bayonet Constitution,” diminished the power of the monarchy (Osorio, 2001). In response to later attempts by the king’s successor, Queen Lili‘uokalani, to restore these powers, a group of European and American businessmen backed by the United States military overthrew the monarchy. On January 17th, 1893, Queen Lili‘uokalani surrendered in an effort to save lives and in hopes she would be reinstated. The Kingdom of Hawai‘i was proclaimed to be the “Republic of Hawai‘i” by coup members (“The Overthrow”, 1999).

Since the Great Māhele and the illegal overthrow of the monarchy, Kānaka Maoli have fought to maintain their connection to the land. For example, in the 1970s, the rural communities of Waiāhole and Waikāne successfully resisted evictions meant to make room for suburban and tourism developments (Lasky, 2014). Local “houseless” communities on Oʻahu also continue to fight for their right to define community and access ancestral land. For example, Puʻuhonua O Waiʻanae is a self-governed village, where on average 250 houseless people live, two-thirds of whom are Kānaka Maoli. What began as a village on the edge of the Waiʻanae Boat Harbor has transitioned into a permanent village community meant to be a place of refuge for all people who have been unable to afford the cost of living in Hawaiʻi. There, people have access to social services and a return to kauhale living. Other such communities exist on the Windward and South sides of the island, with Kānaka Maoli community leaders stepping in to address local homelessness. Building a Partnership

Housing First on O‘ahu

In addition to local community leaders responding to the homelessness crisis, government officials have invested in solving the problem. In 2014, the City and County of Honolulu responded to O‘ahu’s increasing homelessness rates with a flurry of housing policies, including funding for a program based on the Pathways Housing First program model. In contrast to “treatment first” models which assume people need to be “housing ready” (e.g., achieving sobriety, employment, etc.) before “earning” housing, Housing First, as a philosophy and program model, consider homelessness to be primarily an affordable housing problem solved by providing individuals with housing quickly and then, providing wraparound services if desired by participants—or “clients” (Tsemberis, 2010). The approach had been successful in other major US cities, and Honolulu government officials hoped the model would have an impact on O‘ahu.

Housing First Evaluation

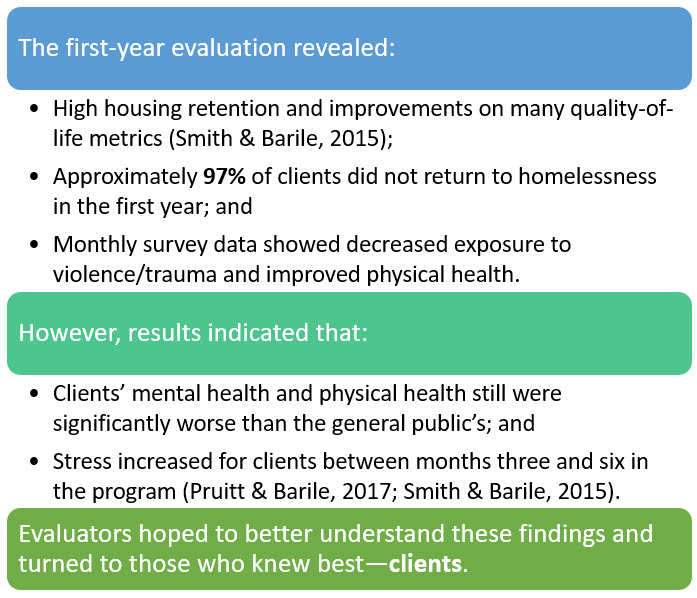

A local service agency implemented the program and contracted with community psychologist evaluators (Drs. Barile and Pruitt) to conduct an evaluation of the program. An evaluation is a systematic investigation of program merits, outcomes, and processes, using social science methodologies (Cousins & Chouinard, 2012). In particular, Drs. Pruitt and Barile were tasked with evaluating the program for fidelity to the model (i.e., how well does the program adhere to the original program model?), housing retention, and cost-benefit analysis (i.e., do the benefits outweigh the costs?). The original evaluation plan was a mixed-methods design, including staff and client interviews as well as monthly client surveys.

Participatory Evaluation

In an effort to better understand the experiences of individuals in the program, community psychologist evaluators decided to engage in a participatory evaluation, which engages non-evaluator stakeholders in the research and evaluation process (Cousins & Chouinard, 2012). Participatory evaluations can be grouped into practical participatory evaluations and transformative participatory evaluations (T-PE). Our project falls within a transformative participatory evaluation approach, which aims to create conditions in which individuals who have traditionally had little access to power can empower themselves. Evaluators felt that T-PE would work well with the Housing First program philosophy, particularly the value of “consumer choice.” By creating a new evaluation process in which the researched become co-researchers, T-PE allowed clients to have more say in the policies and research that affect them. Additionally, with its attention to power and explicit goal of transforming systems, T-PE complemented Dr. Pruitt’s intersectional approach to research and evaluation. Finally, this approach seemed to fit better within the local context, which values cooperation and collaboration over power and competition and traditional hierarchical Western approaches.

Collaborative Partners

In general, participatory evaluations focus on relationships as an important outcome, and this project, likewise, prioritized building relationships between partners. Collaborative partners have included program staff, community psychology evaluators, and program participants—“clients”. While the individuals who hold these roles have changed over time, the partnership has remained stable. In particular, consistency in lead evaluators and a core group of clients has helped maintain the partnership even as case managers and other program staff have shifted. The initial community psychology evaluators consisted of Drs. Barile and Pruitt. Dr. Pruitt was in graduate school at the beginning of the partnership and has now taken on a leadership role in the project. Another community psychologist (McKinsey) joined in 2018 and, along with Dr. Pruitt, worked closely with community partners, attending weekly meetings. These two community psychologist evaluators—two White women in their 20s and 30s from the southern United States—had the most on-the-ground contact with partners. While evaluators stayed relatively stable, program staff has shifted over time. At any one time, program staff consisted of four case managers, two housing specialists, two administrative staff, and an interfaith chaplain/community liaison. However, the individuals who have served in these roles have changed over time. Clients involved in the partnership have also changed over time; however, for the most part, the core group of clients has remained consistent.

In evaluation, it is important to consider the ways in which different partners had different stakes in the project and varying levels of power. An intersectional approach to evaluation necessitates attention to power. In our partnership, clients had the least amount of power—both within the program and within the greater community—and also had the most at stake (e.g., their housing). Program staff also had much at stake (e.g., their jobs) but had considerably more power than clients. Various levels of power also existed among program staff. Case managers, for example, had less decision-making power than upper-level administration. While evaluators had significant power (e.g., determining what results and recommendations are passed along to funders), they were under contract with the program and largely depended on program staff for access to data and ultimately, a successful evaluation project. For the partnership to be successful and equitable, evaluators knew they had to consider these dynamics and how they were informed by the larger socio-historical context. For example, as members of the colonizer group, the community psychologist evaluators were constantly considering the ways in which systems of power attached to their social identities were impacting the group dynamics. In this case, intersectionality was employed as an analytical tool.

Community Assets/Needs

Despite power differentials, the partnership offered the potential to meet the various needs of the diverse partners involved. The T-PE approach was embraced by the program, which was looking for a way to build client feedback into the program model. The participatory evaluation was one way to formalize that process. Additionally, community psychologist evaluators initially had difficulty accessing program data. Clients were hesitant to fill out monthly surveys and case managers were hesitant to encourage clients to complete them for fear of compromising program fidelity related to consumer choice. Case managers who were overburdened with high caseloads in the first year needed a way to see multiple clients at once (Smith & Barile, 2015). Clients expressed a desire for social support, community, structure, and something meaningful to do. The chaplain/community liaison was looking for a way to address these issues. Overall, community psychologist evaluators were looking for a way to better engage with the program without adding to the workload of program staff or stress of the clients.

Assets and Strengths

Thankfully, the partnership allowed for partners to meet these needs by capitalizing on the existing strengths and resources of various partners. For example, one of the biggest strengths was the ongoing commitment to building community and social support among program staff and clients as part of an optional weekly support group. Led by the chaplain/community liaison, the group met to discuss challenges with housing, to provide peer support, and to (re)learn “life” skills. Case managers also participated, some of them having had experienced similar challenges in the past. Dr. Pruitt began attending the group as part of an initial Photovoice project aimed at engaging clients and staff in the evaluation through the use of photography. Building the project and partnership into an ongoing program component was beneficial in that trust between group members had already been established. Over the next five years, the Housing First Community Group, comprising HF clients, program staff, and community psychologist evaluators became an integral part of the program and evaluation design. Additional strengths included the fact that upper-level program staff had important contacts in the community that paved the way for future Photovoice exhibits and dissemination of evaluation findings. The program evaluators had training in participatory and arts-based methods and were able to use this training to inform the evaluation research project. Importantly, program staff and clients were open to collaboration, and all partners were committed to learning from each other from the start. Perhaps most notable were the clients’ strengths. Rarely are individuals who have experience with homelessness or severe poverty considered to have strengths and assets that are beneficial to society. Our work together revealed that this is a significant miscalculation by “housed” individuals. We identified the following:

- Clients were resourceful and insightful, making connections between quantitative outcomes and qualitative outcomes.

- They helped case managers check in on other clients in the program who may have been dubious of case management.

- They assisted in outreach.

- They helped the evaluators interpret survey results and were invested in the evaluation process as a whole.

For example, when survey data showed a decrease in physical and mental wellbeing after six months of housing, program staff and evaluators assumed clients were struggling with transitioning to housed life and considered offering more “life skills” classes. However, the interpretations from the client co-researchers revealed a more complex story. They explained that it took many months of housing before they felt safe enough to come out of the constant state of “fight or flight” they experienced prior to housing. Once they emerged from this state, they were able to take stock of their wellbeing and recognize the trauma they had endured. Some described their reactions in terms similar to post-traumatic stress disorder. Due to their insights, the program was able to address this issue by providing more comprehensive services beyond life skills classes. The value of such contributions is often overlooked in evaluation projects that do not take a participatory approach, and the value of the contributions of those who have traditionally been excluded from the process cannot be overstated.

Participatory Research Project: Photovoice Studies

Throughout our partnership, the Community Group—or “the group”—has collectively produced multiple evaluation reports, participated in community arts projects, and conducted participatory research projects. This section focuses on the two biggest projects which both used Photovoice, a participatory research methodology.

Photovoice Project One

In January 2016, the group chose to conduct a Photovoice project that examined clients’ experiences in the program and gave them the opportunity to speak to the program and the larger community about these experiences. Photovoice seemed an appropriate choice given that it is a community-based participatory research method in which participants use photography to(a) identify and record their personal and community strengths and concerns;(b) engage in critical dialog about them; and(c) communicate these strengths and concerns to policymakers (Wang & Burris, 1997).

As a participatory method, all partners are involved at each stage of the research process, from the development of the research question to the dissemination of findings. Photovoice works to center the voices and experiences of individuals traditionally left out of the research process (Tsang, 2020; Wang, 1999). Thus, the method worked well with our T-PE and intersectional approach. Individuals experiencing homelessness, particularly those who also experience severe mental illness or chronic health conditions, rarely have a say in the research and policies that greatly impact them. This exclusion is largely due to social exclusionary policies and assumptions by the larger society that such individuals are incapable of meaningful contribution to research and practice. Photovoice allowed for both the creation of an inclusive space that centered on client voices and analysis of the processes that tend to restrict inclusion and voice.

As part of this initial three-month study, 18 Housing First clients and two case managers took more than 300 photographs over a four-week period. At that point, most clients had been housed less than a year, and thus, the group decided to focus on the initial transition from homelessness to housing. They took photographs in response to prompts aimed to examine this process (e.g., “How is your life different now?” “What is everyday life like for you?”). Each week, clients and case managers shared photographs with each other and discussed their relevance to the prompt and the overall research question. Then, the group collectively conducted participatory analysis on the photos (see Image 2) and reported the findings in the yearly evaluation report (Pruitt & Barile, 2017). After the conclusion of the Photovoice project, Dr. Pruitt continued attending the weekly community group. As staff turned over, she often took on a facilitator role. A core group of clients also continued to attend and contribute to group agendas. This commitment helped ensure the group continued even in the midst of staff turnover. As several clients noted, having that consistency was meaningful. Throughout the next year, the group engaged in continued participatory evaluation research and practice, assisting in evaluation reports, helping interpret evaluation results, providing peer support to others in the program, and assisting Dr. Pruitt in her research on local media coverage of homelessness. Importantly, the group co-authored an academic journal article in 2017.

Photovoice Project Two

In 2017, HF clients in the group asked Dr. Pruitt to help them design and conduct a follow-up Photovoice study. With increased knowledge of the research process, clients wanted to examine the long-term and continuous nature of the recovery process from homelessness. The group applied for and was awarded a Society for Community Research and Action Mini-Grant to purchase higher-quality cameras. From August–November of 2018, 22 individuals participated in this project (15 clients, four staff members, and three evaluators), most of whom had participated in the 2016 study and had been housed for an average of 3.4 years.

Participatory Analysis

In both projects, the community group conducted a participatory analysis of the photos. During meetings, group members would select a few meaningful photos to share, with the photographer contextualizing the photo by describing where and when it was taken, why it was meaningful, and/or what it represented. The group, then, collectively analyzed the photos by identifying patterns in photos and drawing connections to previously shared photos. In 2018, the group coded photographs using large theme boards (see Image 3). The ultimate goal of the analysis was to identify key themes relevant to the long-term process of transitioning into housing and recovering from the trauma of homelessness. Based on the themes identified during the participatory analysis stage, community psychologist evaluators also conducted a secondary content analysis of all meeting transcripts. Content analysis is a classification process consisting of codifying and identifying themes within qualitative data (e.g., transcripts; Collins et al., 2016). The goal of the secondary analysis was to examine the unique contributions of the Photovoice method and to gain a comprehensive understanding of the recovery process.

Outcomes

Participatory and content analyses of the projects suggested that although housing brought stability to many aspects of life, challenges such as stress, stigma, and everyday struggles persisted for many clients once housed. Additionally, social support and community reintegration continuously appeared as prominent indicators and promoters of recovery from the trauma of homelessness. Other prominent themes identified as relevant to transition to housing and recovery included:

- the importance of projects, hobbies, and goals;

- appreciation of people and environment;

- the stigma surrounding homelessness; and

- reflection on life before and after housing.

While both studies demonstrated the difficulties clients faced with stigma, the first study found that clients felt that the level of the interpersonal stigma they experienced had been reduced with their housed status. However, the pain of previous treatment was still poignant. In the second study, clients continued to discuss stigma; this time, from a macro-level perspective. They discussed the stigma toward “the homeless” that they perceived in the media, local policies, and in the larger community’s attitudes (see Image 4). Notably, they wanted to use the findings from these projects to try to address this stigma and advocate for the homeless community. For more information on study findings, please visit our website at www.hf-photovoiceprojects.com (or see Pruitt et al., 2018).

Dissemination

With social and political transformation as central goals of Photovoice methodology, dissemination of findings was essential to the project. Further, clients consistently explained that part of their motivation for participating in the project was its potential to create social change. As such, extensive dissemination of findings is an important piece of these projects.

Photo courtesy of Dr. Anna Pruitt

Given that findings are informed by the lived experiences of individuals whose perspectives are rarely seen in the dominant public discourse, exhibits were one of the main dissemination tactics to reach a broad audience. In 2016, the group held an exhibit for the first Photovoice project’s photos and findings at Honolulu Hale (City Hall) in collaboration with the program, the City and County of Honolulu, and the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. The exhibit was also displayed at the university’s Hamilton Library in November 2018, along with the second project’s photos and findings. In 2019, the second project’s exhibit was displayed at two other community events, including the Hawai‘i Art and Mental Health Summit and the Homelessness Interfaith Summit. The goal was to reach diverse audiences with varying levels of power and stakes in the program and to center the perspectives of individuals from the margins. Findings have also been disseminated within the academic community. Throughout 2017, HF clients and program evaluators co-authored a research article that reported findings from the first project, which was published in the American Journal for Community Psychology in January 2018 (see Pruitt et al., 2018). Evaluators are currently in the process of preparing a manuscript that shares both participatory analysis findings of the second Photovoice project and secondary content analysis findings. Findings and corresponding recommendations have also been included in annual evaluation reports to the program. Lastly, evaluators developed a website detailing the PV process, projects, and findings.

Impact

The two Photovoice projects also resulted in varied impacts—transformative change, knowledge creation, and methodological insights:

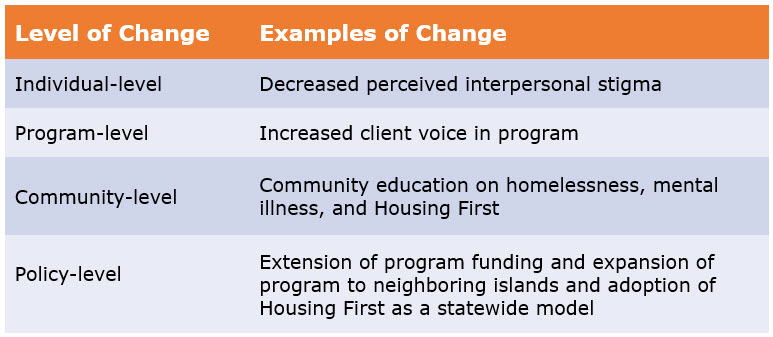

Transformative impact: Both projects sought to achieve a transformative impact by providing a time and space for HF clients to actively reflect on their own lived experiences, offer feedback to the program, and to engage in social action. Recognizing that they had “won the lottery” in being chosen for this pilot program, they wanted to help others by sharing findings from the studies in an effort to change the local homeless service system. Analysis of the impacts of the first Photovoice project revealed transformative change on the individual, program, community, and policy levels (see Table 1; Pruitt et al., 2018).

Table 1. Transformative Impacts

Knowledge Creation: The projects also built knowledge as a result of the lived experiences of the transition to housing and the recovery from homelessness by taking a phenomenological approach to community-based participatory research (Bush et al., 2019). Phenomenology is a research approach grounded in the belief that knowledge can be derived from experience (Racher & Robinson, 2003), and seeks to build knowledge by relying on the accounts of those experiencing the phenomenon of interest (Giorgi et al., 2017). Indeed, as the field of community psychology teaches, the true experts on any given issue are those most impacted by that issue.

Methodological Insight: Lastly, the use of various research methods throughout the projects increased understanding of research approaches used to study lived experience. Intersectionality scholarship argues that research on any given issue calls for diverse approaches and methods (Moradi & Granzka, 2017). In line with this argument, community psychologist evaluators conducted both participatory and content analysis to draw meaning from photos and discussions. Comparison of these methods further emphasized the need for multiple research approaches to comprehensively capture the essence of lived experience. For instance, evaluators found that some themes that were prevalent in photos were not frequently discussed and that some themes prevalent in discussions were not frequently photographed. These findings signal that some topics are hard to put into words, while others are hard to capture visually. Additionally, evaluators encountered difficulty interpreting themes identified through content analysis themselves, revealing how participation and insight from HF clients were crucial to being able to comprehensively and accurately analyze data generated from the projects.

Lessons Learned

Overall, this partnership has been a process of mutual learning for all partners, and this section details the lessons learned engaging in the participatory research process. Notably, this section reflects the lessons learned by the community psychology evaluators involved in the projects. The initial plan for this case study was to include the perspectives of all partners. However, due to COVID-19, this collaboration has not been possible. Thus, this section may be most useful for community psychologist evaluators working in multicultural environments with marginalized communities. We recognize that given the lack of our partners’ voices, this section is necessarily incomplete. Perhaps the first lesson, then, is for community psychologists to be aware that our perspectives are not universal but are situated in a larger context informed by intersecting systems of power. One of the most important lessons included learning that taking on the researcher role could be difficult for clients.

While participatory researchers generally assume that more ownership of and voice in the research project is desirable and “empowering,” our work showed that taking on this role comes with unique challenges (McKinsey & Pruitt, 2019). For example, clients did not take any photographs the first few weeks of the second Photovoice project, despite the fact that they had initiated the project themselves. While one staff member worried that this hesitancy meant they did not want to participate, group discussions suggested that clients were taking more time because they wanted to “do it right,” and that they were extremely anxious about potentially making a mistake. Community psychologists working with marginalized groups should consider these challenges and address them throughout the project for some of the strategies we used to address these challenges).

Another lesson learned through the partnership is that dissemination can be one of the most power-laden stages of research. For example, balancing power among stakeholders during exhibit planning proved difficult. During the first exhibit at Honolulu Hale (city hall) in 2016, homelessness was a hot topic in the local media, and the exhibit was taking place during an election year. The program also wanted to use the exhibit as an opportunity to educate the community on its other housing programs. Thus, many higher-powered stakeholders now had a vested interest in the project—which we acknowledged could be both advantageous and challenging for the group’s goals. Beforehand, we talked as a group about the potential for the media or politicians to usurp our project to push agendas not necessarily in line with our own. The group collectively decided that the risk was worth the potential benefit of advocating for the program and others still experiencing homelessness. The exhibit received significant press coverage and was attended by the mayor and other prominent politicians, and the group was satisfied with the overall event. However, the negotiation and planning were daily stressors for evaluators, who served as mediators in these negotiations.

Additionally, the co-authoring of the journal article revealed the power dynamics inherent in academic writing. As hooks (1989) reminds us, the writing of research takes place within a context and that this context often supports white dominance. For example, hooks (1989) points out that White scholars make the mistake of not recognizing that writing occurs within a “culture of domination” and fail to understand power and context, and thus, their work often reinforces that domination. As White community psychologists, we found that we must be cognizant of the impact of this context at all stages of the research process if we were to (co)produce socially responsible research. In fact, researcher self-reflexivity, while necessary, was not enough. In addition to being aware of our own positionality within this web of power, we also needed to be critical of the very conventions that we relied upon and the process of power inherent in those conventions. We found that we needed to shift our focus from identity groups (based on race, gender, homeless status, etc.) to context or process.

Other lessons learned included learning to balance calling attention to differences among partners (e.g., related to power and skills) with recognizing our similarities. We also discovered that relationships were the most integral part of the research and knowledge-building process. It was clear that clients found the relationships they built with each other, the staff, and the evaluators to be most important to their continued investment in the partnership and even to their own recovery processes. Similarly, staff and evaluators found these relationships enriching and sustaining. Evaluators realized that they were as much a part of the group as any other members and found that to over-emphasize differences between them and the group members, however well-intentioned, could be offensive to some group members. For example, Dr. Pruitt found that calling attention to client “expertise” in understanding homelessness and the housing process served to distance herself from clients, and clients responded by emphasizing that they were more similar to her than different. One of the strategies that helped to reconstruct the assumed hierarchy of knowledge and skills (in any direction) was engaging in arts-based projects. With these projects, we were all simultaneously learning new skills and at times, learning from other clients with art backgrounds helped teach the group. In this way, clients, staff, and evaluators were on the same level, learning together.

Looking Forward

Photo courtesy of Dr. Anna Pruitt

Recognizing the value of art in relationship-building, self-healing, and social action, at the conclusion of the second Photovoice project, the community group decided to form an arts hui (group) to learn various art techniques and to create art for themselves and for social action. For example, one of the art projects included a “positive signs project.” During one of the Photovoice discussions on stigma, group members questioned why public signs were always so negative, saying “don’t do this; don’t do that.” So, the group decided to engage in a sign project that distributes positive messages (see Image 7). For example, in response to signs instructing people not to sit or lie on public sidewalks (effectively criminalizing homelessness), one group member suggested the group make signs that inform people where they can sit (see Image 8). The group has also engaged in the art of cooking, learning new methods for creating affordable and healthy dishes.

Photo courtesy of Dr. Anna Pruitt

Unfortunately, in March 2020, the COVID-19 Pandemic halted the weekly group meetings that have sustained this partnership. While all partners hope to continue the weekly meetings as soon as it is safe, it is unclear when or how to go about reconvening given the fact that many group members (including staff, clients, and evaluators) experience chronic health conditions that put them at risk for severe disease. While the group attempts to stay in contact via phone and email, many group members lack regular access to this technology. Some of us have remained in contact via the mail, and evaluators are working to build capacity to meet virtually. For now, however, the future of the group is uncertain although the overall partnership continues.

Recommendations

Based on this partnership experience, the community psychologist evaluators have recommendations for other community psychologists working in similar settings with similar groups—particularly those community psychologists interested in intersectional and participatory approaches. First, rigorous qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods research can be conducted collaboratively with individuals who have significant housing, mental health, and physical health challenges. Even individuals with ongoing psychosis were significant and essential contributors to the research project and were core leaders in the partnership. Community psychology practitioners working with such groups should not discount the abilities of community partners, and rather, should consider amending their practice by:

- Remaining flexible. Always have a plan but be willing to change it based on partner needs or changes in the context. Importantly, be willing to try something new and continue to seek ways to use the strengths of the community in meeting the needs and goals of the partnership.

- Thinking outside the box. Consider multiple avenues for participation and contribution. For example, we found that having a non-hierarchical, flexible group format with less structure helped produce a more inclusive environment for individuals who may have mental health challenges. It was also more culturally appropriate. Additionally, consider alternative or innovative research methods and ways of disseminating findings. We have already pointed to the value of arts-based approaches when working to center voices typically overlooked in research and practice. Intersectional community psychology practice might consider engaging in similar methods.

- Being willing to be wrong. Rarely do we get it right the first time. Making mistakes and conflict is an unavoidable part of any partnership and indeed, any authentic relationship. We found that some of our community partners reacted to conflict differently and more subtly than we expected. This reaction was an interaction of power differentials and also cultural and class differences. Indeed, differences even existed amongst community psychologist evaluators. Therefore, we had to ask for input from partners regularly and to investigate acceptable ways to address conflict. Importantly, we had to be willing to be wrong and work toward making it right without being defensive.

- Building authentic relationships. Partnerships will be greatly enriched if they are built upon authentic relationships between people who genuinely enjoy each other’s company. We found that laughing together, eating together, and being vulnerable with each other were important aspects of building relationships among partners.

Additionally, we encourage relying on intersectionality analysis and praxis at each stage of the partnership. This approach will likely require constant attention to power and researcher flexibility. Often our community contexts can unintentionally reinscribe hierarchical and oppressive structures. While partnerships consist of multiple and complex relationships, and these relationships worked together to produce new knowledge, community psychologists should consider how power affects the knowledge produced and what role they might be unintentionally playing in the reproduction of oppressive structures. With such attention to power, community psychologists can facilitate the co-production of meaningful, transformative knowledge which extends beyond the patronizing trope of researchers “giving voice” to marginalized groups. Of course, this approach will require flexibility. As TallBear asserts, “A researcher who is willing to learn how to “stand with” […] is willing to be altered, to revise her stakes in the knowledge to be produced” (2014, p. 2). For community psychology practitioners, especially those working with marginalized populations, the importance of showing up and doing what you say you are going to do cannot be underestimated.

In Hawaiʻi, as in homelessness services, people come and go frequently. Hawaii sees high rates of turnover in residents and is said to be a “revolving door,” and homeless services is a field notorious for high turnover in social workers, outreach workers, and case managers. Many clients simply expected evaluators and other group members to leave, and they frequently mentioned how much it meant to them that we continued to come every week. One of us (Dr. Pruitt) recalls how one of the core client members continued to be shocked that she remembered his name every week, more than 4 years into the project. In other words, consistency was key to building trust. One of the clients mentioned that it meant a lot to him to know that he was an important part of the group and that if he didn’t show up, other group members would wonder where he was. Indeed, if someone did not show up for a couple of meetings in a row, the group would often designate someone to check in on them to see if they were doing alright. Showing up, while it may seem like the least we can do, makes all the difference in building a strong partnership among those who have been socially excluded.

The reframing of the role of the trained researcher from offering expertise and “teaching” to showing up, standing with, and learning from the community is central to achieving equitable engagement and partnerships. Indeed, it became abundantly clear early in the Photovoice projects that HF clients did not expect perfection from us (i.e., in the ways we facilitated discussions or explained certain research concepts), but they did expect us to be present. It was this shared dedication to the project’s goals, commitment to showing up every week, and excitement in creating transformative change that strengthened the partnership most. Additionally, it can be easy to get caught up in the notion that trained researchers have something to teach community members, especially marginalized community members. However, it can be more difficult to see the ways in which traditional researchers can learn from community members. As trained researchers, we often left Photovoice sessions shaken and awakened by clients’ insights.

Conclusion

We have found that when an alternative type of space is created, people and knowledge thrive, allowing us to move beyond respect for diversity. Going beyond respect for diversity, this project demonstrates a space in which individuals of multiple races, classes, and genders worked together to build community, conduct rigorous research, and advocate for social justice. Ultimately, this case study sought to emphasize how to use community psychology values to conduct rigorous, long-term participatory research using innovative methods, and we argue that community psychology practice is incomplete without an intersectional approach. Community psychologist researchers and practitioners should not assume that collaboration and participation are enough to overcome pre-existing power dynamics and oppressive structures. Instead, they should also engage in constant reflexivity and recognize moments of subtle resistance. We hope we have demonstrated in this case study that community psychology practice should involve an intersectional critical praxis that investigates power dynamics related to various and intersecting oppressions and identities. “Practitioners who would be drawn to intersectionality as critical praxis seek knowledge projects that take a stand; such projects would critique social injustices that characterize complex social inequalities, imagine alternatives, and/or propose viable action strategies for change.” (Collins, 2015)

For the detailed Field Notes and Reflections on Field Notes for this case study, please contact Dr. Anna Pruitt.

From Theory to Practice Reflections and Questions

- How is the theory of intersectionality helpful in a participatory evaluation process? What are other areas where using an intersectionality approach might be beneficial?

- Pruitt et al. (2021) shared, “We hope we have demonstrated in this case study that community psychology practice should involve an intersectional critical praxis that investigates power dynamics related to various and intersecting oppressions and identifies.” Reflect on how “power dynamics” and research further what this means in general and provide a short statement.

- Name one way you can think outside of the box within your own work or area(s) of interest as a community psychologist or other field if not community psychology.

References

Anzaldúa, G. (1987). Borderlands/La frontera: The new mestiza (4th ed.).

Barile, J. P., & Pruitt, A. S. (2017). The impact of place and time on homelessness rates in major U.S. cities. Paper presented at the Society for Community Research and Action Biennial Conference, Ottawa, ON, Canada.

Bilge, S. (2014). Whitening intersectionality. In W. D. Hund and Lentin (Eds.). Racism and sociology (pp. 175-205). Münster, Germany: LIT Verlag.

Bush, E. J., Singh, R. L., & Kooienga, S. (2019). Lived experience of a community: Merging interpretive phenomenology and community-based participatory research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919875891

Collective, C. R. (1982). A Black Feminist Statement: The Combahee River Collective. In G. T. Hull, P. Bell-Scott, & B. Smith (Eds.), All the women are White, all the Blacks are men, But some of us are brave: Black women’s studies (pp. 13–22). The Feminist Press at CUNY.

Collins, P. H. (2015). Intersectionality’s definitional dilemmas. Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 1-20. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112142

Collins, S. E., Jones, C. B., Hoffmann, G….& Clifasefi, S. L. (2016). In their own words: Content analysis of pathways to recovery among individuals with the lived experience of homelessness and alcohol use disorders. International Journal of Drug Policy, 27, 89–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.08.003

Cousins, J. B., & Chouinard, J. A. (2012). Participatory evaluation up close: An integration of research-based knowledge, Information Age Publishing, Inc.

Crenshaw, K. W. (1989). Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 139–67.

Crenshaw, K. W. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241-1299.

Giorgi, A. P., & Giorgi, B. M. (2003). The descriptive phenomenological psychological method. In P. M. Camic, J. E. Rhodes, & L. Yardley (Eds.), Qualitative research in psychology: Expanding perspectives in methodology and design (p. 243–273). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10595-013

Gramsci, A. (1971). Selections from the prison notebooks of Antonio Gramsci. (Eds. and trans., Q. Hoare and G. Nowell Smith): International Publishers.

Grzanka, P. R. (2020). From buzzword to critical psychology: An invitation to take intersectionality seriously. Women & Therapy, 43(3–4), 244–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703149.2020.1729473

Goodyear-Ka‘ōpua, N. (2014). Introduction. In N. Goodyear-Ka‘ōpua, I. Hussey, & Wright, E. K. (eds.) A nation rising: Hawaiian movements for life, land, and sovereignty. Duke University Press.Hawai‘i Data Collaborative (8 May 2020). (Updated) Modeling Suggests Substantial Increases in the Financial Vulnerability of Hawaii’s Families. Retrieved from: https://www.hawaiidata.org/news/2020/5/8/updated-modeling-suggests-substantial-increases-in-the-financial-vulnerability-of-hawaiis-families

Hawai‘i Tourism Authority. (2019a). 2019 Annual visitor research report. Retrieved from: https://files.hawaii.gov/dbedt/visitor/visitor-research/2019-annual-visitor.pdf

Hawai‘i Tourism Authority. (2019b). Fact sheet: Benefits of Hawai‘i’s tourism economy. Retrieved from: https://www.hawaiitourismauthority.org/media/4167/hta-tourism-econ-impact-fact-sheet-december-2019.pdf

Books, B. (1989). Talking back: thinking feminist. Thinking black. South End Press.

Lasky, J. (2014). Waiāhole-Waikāne. A nation rising: Hawaiian movements for life, land, and sovereignty. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822376552-006

McKinsey, E., & Pruitt, A. S. (2019). “Am I doing this right?”: Helping Housing First clients navigate difficulties conducting community-based participatory research. The Community Psychologist, 52(3), 65-68.

Minerbi, L. (1999). Indigenous management models and protection of the Ahupuaʻa. The ethnic studies story: politics and social movements in Hawaiʻi. University of Hawai‘i Press.

Moradi, B., & Grzanka, P. R. (2017). Using intersectionality responsibly: Toward critical epistemology, structural analysis, and social justice activism. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(5), 500–513. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000203

National Alliance to End Homelessness. (2020). State of Homelessness: 2020 Edition. https://endhomelessness.org/homelessness-in-america/homelessness-statistics/state-of-homelessness-2020/

Office of Hawaiian Affairs (OHA). (2019). Native Hawaiian homeless population on Oʻahu: Data from point-in-time count, January 2019. Presentation at the 2019 Homeless Awareness Conference, Honolulu, HI. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44567-6_10

Osorio, J. K. (2001). “What kine Hawaiian are you?” A Moʻolelo about nationhood, race, history, and the contemporary sovereignty movement in Hawaiʻi. The Contemporary Pacific,13(2), 359-379. 10.1353/cp.2001.0064

Padgett, D., K. Henwood, B. F., & Tsemberis, S. J. (2016). Housing first: ending homelessness, transforming systems, and changing lives. Oxford University Press.

Partners in Care. (2020). 2020 Oahu Point in Time Count Comprehensive Report. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5db76f1aadbeba4fb77280f1/t/5efa984a8ae4f774863509e8/1593481306526/PIC+2020+PIT+Count+Report+Final.pdf

Plunkett, R., Leipert, B. D., & Ray, S. L. (2012). Unspoken phenomena: using the photovoice method to enrich phenomenological inquiry. Nursing Inquiry, 20(2), 156-164. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1800.2012.00594.x

Pruitt, A. S. (2019). Racial Equity in Honolulu County Homelessness Services. Prepared for Partners in Care, O‘ahu’s Continuum of Care, Honolulu, HI.

Pruitt, A. S., & Barile, J. P. (2017). Housing First program, year two evaluation. Prepared for the City and County of Honolulu and the Institute for Human Services, Honolulu, HI

Pruitt, A. S., & Barile, J. P. (2020). Unsheltered in Honolulu: Examining Unsheltered Homelessness in Honolulu from 2017-2020. Prepared for the City & County of Honolulu and Partners in Care, Honolulu, H.I.

Pruitt, A. S., Barile, J. P., Ogawa, T. Y., Peralta, N., Bugg, R., Lau, J., Lamberton, T., Hall, C., & Mori, V. (2018). Housing First and photovoice: Transforming lives, communities, and systems. American Journal of Community Psychology, 61(1–2), 104–117. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12226

Pruitt, A. S., McKinsey, E., & Barile, J. P. (2020). “A State of Emergency”: Dominant Cultural Narratives on Homelessness in Hawai‘i. Journal of Community Psychology, 48(5), 1603-1619.

Racher, F. & Robinson, S. (2003). Are phenomenology and postpositivism strange bedfellows? Western Journal of Nursing Research, 25(5), 464-481. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945903253909

Shinn, M., & Khadduri, J. (2020). In the midst of plenty: Homelessness and what to do about it: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Smith, A., & Barile, J. (2015). Housing First program one-year evaluation. Prepared for the City and County of Honolulu and the Institute for Human Services, Honolulu, HI

Society for Community Research and Action (SCRA). (2011). Competencies for Community Psychology Practice. http://scra27.org/what-we-do/practice/18-competencies-community-psychology-practice/

Society for Community Research and Action (SCRA). (2020). Who we are: Principles. http://scra27.org/who-we-are/

Stover, J. S. (1997). The Legacy of the 1848 Māhele and Kuleana act of 1850: A Case Study of the Lāʻie Wai and Lāʻie Maloʻo Ahupuaʻa, 1846-1930. [Masterʻs thesis, University of Hawaiʻi]. Scholar Space.

TallBear, K. (2014). Standing with and speaking as faith: A feminist-indigenous approach to inquiry [Research note]. Journal of Research Practice, 10(2), Article N17 http://jrp.icaap.org/index.php/jrp/article/view/405/371

The Overthrow. (1999, June 16). Star-Bulletin. http://archives.starbulletin.com/1999/06/16/millennium/story7.html

Truth, S. (1851). Ain’t I a Woman? Ohio Women’s Rights Convention, Akron, OH.

Tsang, K. K. (2020). Photovoice Data Analysis: Critical Approach, Phenomenological Approach, and Beyond. Beijing International Review of Education, 2(1), 136–152. https://doi.org/10.1163/25902539-00201009

Tsemberis, S. (2010). Housing First: The pathways model to end homelessness for people with mental illness and addiction. Hazelden.

US Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2020a). Economy at a glance. https://www.bls.gov/eag/eag.hi.htm

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2020b). Local area unemployment statistics. https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LASST150000000000003?amp%253bdata_tool=XGtable&output_view=data&include_graphs=true

U.S. Census Bureau. (2019). American Community Survey, 2019. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/honolulucountyhawaii

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). (2012). Homeless Definition. https://files.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/HomelessDefinition_RecordkeepingRequirementsandCriteria.pdf

Wang, C. C. (1999). Photovoice: A participatory action research strategy applied to women’s health. Journal of Women’s Health, 8(2), 185-192. http://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.1999.8.185

Wang, C., & Burris, M. A. (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior, 24(3):369-387. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F109019819702400309

Watson, T. K. (2010). Homelessness. In C. Howes & J. Osorio (eds.) The value of Hawaii: Knowing the past, shaping the future. University of Hawaii Press.

Weber, L. (2009). Understanding race, class, gender, and sexuality: A conceptual framework (2nd ed). Oxford University Press.

Feedback/Errata