7 Program Evaluation: A Fundamental Component in Effective Community Practice

Dr. Patricia O’Connor. Ph.D.

This case story expands the traditional single-case study format to include multiple mini-case studies from which “lessons learned” are extracted through evaluation-based community psychology practice.

The Big Picture

In this chapter I modify and expand the traditional single-case study format to include multiple mini-case studies from which I extract “lessons learned” through my evaluation-based practice of community psychology (CP).

Program evaluation plays an important, structural role in its contributions to the assessment of the intervention work of change agents, here CP practitioners, and relevant stakeholders who work together to design and implement needed community-based programs. My aim here and in all of my work is to encourage an evaluation mentality in CP practitioner-change agents. If these change agents develop interventions with an evaluation mentality, that is, with program evaluation as a core part of planning, design, and implementation, the resulting evaluative feedback can provide validation of the effectiveness of programmatic efforts, and thus, of change agents, or illustrate the need for substantive changes in aspects of the intervention efforts. The inclusion of evaluation strategies can assist program implementers/change agents in identifying the critical elements to ensure meaningful interventions and to provide evidence of the viability of replication. Additionally, we must recognize both the CP-based values (social justice, sense of community, empowerment, etc.) which underlie the development of community practice interventions and the critically important role of a change agent who incorporates a program evaluation mentality into the design of those interventions. Program evaluation thus becomes an essential tool in the practice of CP.

The overall aim of community psychologists’ work is the improvement of participants’ quality of life; some examples include Beauregard et al. (2020), Lin et al. (2020), O’Connor (2013), O’Shaughnessy and Greenwood (2020), Stewart and Townley (2020), and Suarez-Balcazar (2020). Improving quality may range from enhancing individuals’ sense of well-being to ensuring needed supports; some examples include DaViera et al. (2020), Goodkind et al. (2020), Maleki, et al. (2020), Shek et al. (2017), and Wadsworth et al. (2020). However, confirming the value of such work or appropriately modifying it can only be accomplished through the inclusion of community-based program evaluations. The essential questions for program implementers or change agents are whether a proposed program is appropriate, whether the implemented program is as planned or how it has changed, and whether the program outcomes are as hoped for or as expected. Thus, developing and implementing interventions must be paired with evaluating the initial designs, implementations, and/or outcomes of those programmatic interventions, all of which can improve participants’ quality of life.

My work and my career focus have been two-fold: as a professor in a small college in upstate New York teaching a program evaluation course in a master’s program, and as an evaluation consultant, engaging in numerous small, primarily local and large, state-based and national program evaluations. From that work, I have identified seven lessons regarding the use of program evaluation strategies that are offered as guides to those in the CP practice of evaluating community-based programs. I also provide three principles that serve as guides for program evaluators. The seven lessons, with illustrative mini-case studies, are based on two kinds of evaluation projects: student-based through my graduate program evaluation course and consultation-based through my CP practice. The former evaluations emerge from a course requirement for students to participate in the design and implementation of a group evaluation project and the latter projects include my consultation-based evaluations of specific programs or organizations. These mini-case studies, with their “lessons learned” immediately following, document that some efforts were successful and, not surprisingly, some were not.

Mini-Case Study One

The Executive Director (ED) of a human services agency that provides residential treatment for adolescents was interested in front-line employees’ perceptions of their work environments. The ED, a manager, and an assistant met with the graduate students and me to discuss the ED’s purpose for the evaluation: to learn how to make the organization a “best place” to work. We agreed that interviews with front-line workers would be the most appropriate way to collect data as there could be flexibility with open-ended questions. The manager would provide access to front-line workers. The meeting ended quite satisfactorily, with a potential schedule for the next steps, and the ED, manager, and assistant left.

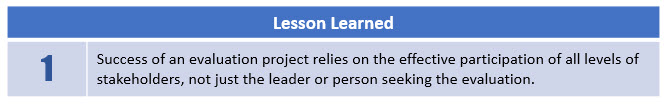

Students walking down the hallway after the meeting overheard the manager say to the assistant, “They should just do their f*** jobs!” illustrating that the manager had little interest in soliciting feedback from employees. This attitude was reflected in the difficulty students had throughout the project, first in getting access to employees, and second, in having employees agree to be interviewed. Some employees expressed concern that their interview information might not remain anonymous; the manager was not considered trustworthy. Students completed interviews but fewer than expected and with less useful information than planned or expected. Seven overarching lessons learned are depicted in tables below.

Mini-Case Study Two

A local County Commissioner of Mental Health was interested in whether children’s visits to an Emergency Department (ED) could have been avoided, particularly among those children receiving assistance from the County. The question was whether the children were in contact with any service agencies and whether that contact should have resulted in interventions that would have precluded the ED visit. Students in the graduate Program Evaluation class and I met with the Commissioner and formulated a plan for record reviews of intake information at the ED of the local hospital. Although students were reviewing unredacted records, Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was not considered necessary; unpublished program evaluations do not require IRB review.

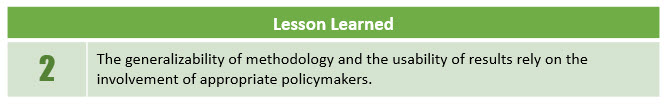

Students presented the results to the Commissioner who was able to work with the Department of Social Services to develop preventive interventions to reduce children’s unnecessary use of the ED. The success of this project resulted in the Commissioner taking the methodology to the relevant State Offices and the data collection strategy was replicated in nine counties. Three factors led to this generalizability: the quality of the student-designed project, the Commissioner’s appreciation of, and reliance on relevant data, and the Commissioner’s interest in expanding the use of relevant methodologies and usable information as a foundation for decision-making.

A local prevention program focused on specific issues related to illegal substance use among younger people as required by their funding sources. Through my ongoing relationship with the program director as the program’s evaluation consultant, we conducted multiple evaluations, including focus groups/interviews with key leaders in the community, an asset-liabilities assessment of a specific neighborhood, and pre-post surveys with a summer leadership program for high school students, among several other projects over a period of approximately six years. Below are examples of successful and not-so-successful implementations of those evaluations.

Mini-Case Study Three

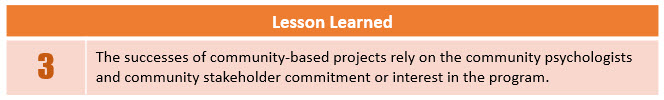

In one particularly effective evaluation, students conducted an observational assessment of a neighborhood to identify both assets (open stores, schools, churches, shops, etc.) and liabilities (closed stores, vacant houses, empty lots with trash). Although the student evaluation groups typically included only five or six participants, this self-selected group comprised 14 very dedicated students, divided into seven pairs for the observations and interviews. The paired students divided the neighborhood into approximately equal manageable areas, did the observations in pairs, and conducted interviews (with a structured interview developed during class time) to obtain residents’ perceptions of the neighborhood. The collected information enabled the program director to develop strategies to advocate for neighborhood improvements and to identify specific locations for program development. The degree of determined and dedicated student involvement led to the clear success of this evaluation effort.

Mini-Case Study Four

In another evaluation, the program director of the same substance abuse prevention program requested that students conduct interviews with people presumed to be key stakeholders to obtain their feedback on the program. Working with the program director, students identified approximately 40 locally based, potential stakeholders, including religious leaders, politicians, educators, local business owners, and others. The project itself was built on the expectation that people in the community would be familiar with, if not involved in, the work of the project. However, these stakeholders-leaders, all of whom the students contacted directly, were not sufficiently knowledgeable about, or in some cases, invested in the work of the program to participate in the interview process, resulting in inadequate numbers of completed interviews and thus, inadequate feedback regarding program implementation. Here the lack of success seems tied to the lack of interest or commitment on the part of the external stakeholders, most of who did not view themselves as stakeholders at all.

Mini-Case Study Five

To evaluate a summer leadership program for high school students offered by the same substance abuse prevention program, the graduate students in the program evaluation course and I met with the program coordinator to identify the aims and activities of the program which would enable the students to develop pre-and post-surveys. The coordinator who reported to the program director did not seem particularly interested in any kind of evaluation. After the initial meeting, the students were virtually unable to connect with the program coordinator who simply did not respond to emails or phone calls. The students, under my direction, finally developed a draft survey to enable some completion of the project before the end of the semester. The lack of success here reflected the lack of commitment on the part of the internal stakeholder.

Mini-Case Study Six

In working with a program director in an agency that provides support to underserved, generally homeless, people, I suggested conducting a focus group with people who were receiving services to solicit their input in developing strategies to address their needs, which could result in modifications of existing programs. The program director asked approximately six or seven people to participate and four arrived at the designated time. Transportation costs in the form of bus passes and given gift certificates to a local chain were offered to encourage participation and to compensate for their time. However, the focus group did not achieve the expected outcome in that all participants had extensive experiences with such agencies/programs and were familiar with the kinds of questions that might be asked and with the range of what they perceived that agencies might consider acceptable responses. Thus, the circumstances under which the focus group was conducted, that is, in the agency itself with a peer as a co-facilitator, led to repetitions of stories and statements which only affirmed what was already happening, rather than suggestions for novel approaches to addressing the needs of program participants. Here the previous experiences of the participants framed and even limited the range of their contributions.

Mini-Case Study Seven

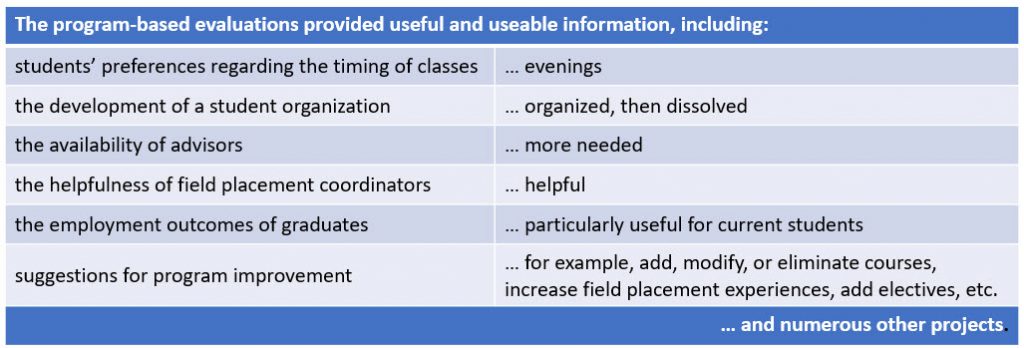

As director of a graduate program in Community Psychology, I have consistently encouraged student-designed and implemented process and outcome evaluations of the program itself and of other offices at the College, for example, access to registration and financial aid offices, availability of library, and separately, food services.

Participation in these kinds of evaluations provided the students with meaningful, hands-on experiences with the process of evaluation and with the programmatic commitment to assessing the usefulness and value of one’s work. Only one among numerous CP program evaluations yielded a particularly negative response; when asked the reason for not continuing in the program, one person responded, “I hate [the program director who happens to be the author!].”

Several of my evaluation experiences have reinforced the importance of effective process evaluations, particularly of observation. Three mini-case studies below illustrate that importance, two from one setting and the third from another setting which is described below. The first setting was a well-funded arts-education program that comprised artists collaborating with teachers in the delivery of primary school curricula. Storytellers emphasize the logical progression of a story (beginning, middle, end) for kindergartners and first-graders and math operations (addition and subtraction) for second and third graders; dancers express the meaning of words in movement (lean forward, then backward for wax and wane or ebb and flow).

This arts-education collaboration can result in improved grades for students, which can be documented over time through appropriate outcome measures, for example, quarterly grades compared with the previous year, or compared with another no-arts unit. However, the actual viability and replicability of the program will depend on two factors: first, the support of the classroom teachers through their involvement in the collaborative process, and second, the actual use of the arts by the change-agent artists.

Mini-Case Study Eight

An illustration of the first factor, support of the classroom teacher, was my effort to observe both the teacher-artist collaboration and the actual artist’s presence in the classroom with at least two observations of each teacher. One second grade teacher was determinedly not interested in participating in any aspect of the process, though expected to do so by the principal; the teacher even stated to me, “You can do your little [arts-education dance] program here [in the classroom] but I am not going to be involved.” That teacher retired at the end of that school year. Most other observations were conducted with the enthusiastic involvement of teachers and artists. One other significant observation was of the grade-level teacher-artist planning meetings to select the curriculum for the artistic mode of delivery. After the first year of the program, the planning meetings became more about setting up the calendar than about modifying or expanding the content and mode of the artists’ delivery of the curriculum. That focus, on the calendar rather than content, reflected the decreasing commitment of the teachers to effective participation in the process of teacher-artist collaboration.

Mini-Case Study Nine

An illustration of the second factor, actual use of the arts by the artist, an effective songwriter/poet/musician collaborated with a fourth-grade teacher in the delivery of a poetry unit with the expectation that the artist would use music to demonstrate the role of rhythm in poetry. In the observed classroom experience, the artist used her own skills in poetry-writing to deliver the lesson rather than her musical talent and musical instruments. The outcome of improved grades for the students was, in fact, related to the skill of the artist as a poet than to the artist as a musician in the delivery of the curriculum. This effectively precluded the presumed replicability of the teacher-artist collaboration. Although such a conclusion would not have been drawn without the evaluator’s observation of the classroom exercise, there were also numerous observations of the effective and appropriate implementation of the collaboration as designed.

Mini-Case Study Ten

An entirely different example reflects the importance of observation in an entirely different setting, a national organization with a focus on a specific medical condition. The organization had developed an extensive curriculum, a set of nine chapters with accompanying slides, for medical professionals to bring current, in-depth information to those with the condition and to inform the general public about the condition. The aim of the evaluation was the assessment of the effectiveness and usefulness of this standardized curriculum. As the evaluator, I included observation of each of the three planned implementations of the curriculum, one in a rural setting with people with the condition, one in a university with providers, caretakers, and people with the condition, and a third in an urban setting with providers and caretakers, primarily parents and family members of children with the condition. The observation revealed that the actual use of the curriculum varied widely across the three settings. The physician-presenter in the rural setting discussed the first several chapters; the multiple presenters in the university setting each reviewed their own areas of expertise without reference to the curriculum, and the presenters in the urban/primarily family setting focused on one chapter in the curriculum which did not overlap at all with the rural presentation. Participants in each setting completed pre-post surveys which demonstrated some increase in knowledge about, and understanding of, the condition across the three settings but clearly those improvements were not related to the actual use of the curriculum. Again, the importance of observation is demonstrated in that the conclusion could only have emerged through my evaluator observation of each implementation.

Mini-Case Study Eleven

In the mid-1990s a local philanthropic foundation began to support locally-based academic-community collaborations through mini-grants, and I applied for and received one of the first. Upon the completion of that grant, I was subsequently approached to collaborate with a variety of community-based programs and agencies over a period of years. These included focus groups with elderly residents of a public housing project to assess their satisfaction (which impacted planned renovations of the housing project), and observations of an advisory board for a child sexual abuse intervention program to identify strategies to enhance the Executive Director’s success with the Advisory Board (one obstreperous person resigned; the Chair reorganized meeting structure). The success of each led to my being contacted by subsequent community agencies and programs to participate in a joint submission to the funding source as the value and usefulness of engaging in evaluation activities became more evident. Here the overall success emerged out of my previous experiences and my local reputation.

Mini-Case Study Twelve

As part of an overall assessment, another national organization/foundation with a focus on differently-abled individuals was interested in whether locally-based programs which they funded were using strategies that matched the vision and mission of the national organization and whether the implementations were resulting in the desired outcomes. Most local program directors were understandably proud of their own efforts, the extent of local participation, and the outcomes of the programs. As the evaluator for the national organization, I undertook the task of assessing six of the local programs (somewhat randomly selected) to identify both aspects that were congruent with the national organization’s goals and objectives and those that needed modification to increase their rates of success. These program directors were willing to participate in the evaluation activities but were also accustomed to receiving only praise for their efforts in initiating and managing their programs. My evaluation reports for each program documented their successes but also included recommendations for improvement. The reports were not well received; directors who had welcomed me, participated actively in the evaluation activities and seemed to accept and even welcome verbal recommendations at the end of each visit, did not appreciate having any of what they perceived as less than positive results in a written report. The outcome was the termination of the entire evaluation project.

Mini-Case Study Thirteen

In one New York State-based evaluation, six counties were selected to participate in a public health intervention and were asked to different their own program designs in their efforts to achieve the desired public health outcome. At the end of the evaluation period, some strategies were clearly more effective than others which led to the adoption, or at least the encouragement of the adoption, of those strategies state-wide. As the evaluator I had assured each of the participating counties that their results would be anonymous, that is, the State as the funding source would not know which counties were successful and which were not. The need for that promise of anonymity was essential because the local staff was concerned that future funding could be affected by the State staff’s knowledge of specific outcomes. At the end of the project, with positive results clearly disseminated, the State staff requested rather strongly that the anonymity be unveiled so that the successful and not so successful counties be identified. I refused, based on the ethics of my adhering to my promise. That ethical decision led to the termination of that relationship!

Mini-Case Study Fourteen

Another instance of ethical difficulties was in the final first-year evaluation report of two-year community-based, federally-funded project which required collaboration across multiple human service agencies. Funding for year two was based on the viability of the project and commitment of the agencies, both of which were to be documented in the evaluation report. A new project manager, who started just weeks before the first-year report was due, requested changes in the report which would enhance the appearance of a positive outcome for year two, but which somewhat misrepresented the actual data. Discussion ensued resulting in the project manager asserting her position as manager and me asserting my role as evaluator with my intention to adhere to the independence of the evaluation process and outcome. The awkwardness of the situation for me resulted in my submitting only a hard copy (in the days before electronic submissions) on the day the report was submitted, precluding the manager’s interest in, and possibility of making changes in the report.

Conclusion

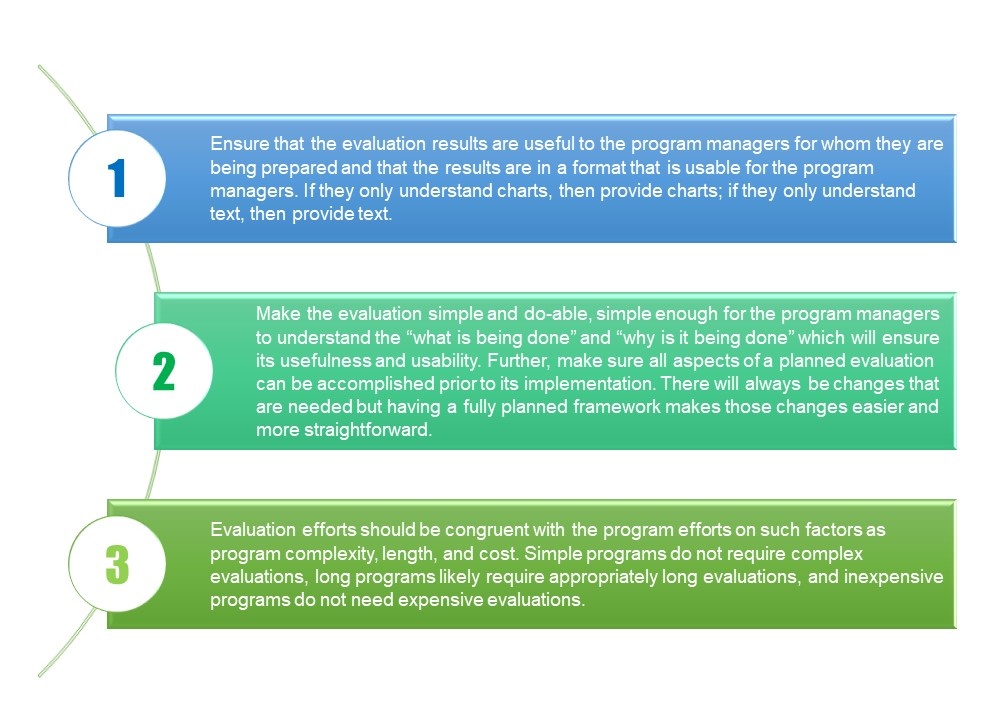

This was a series of mini-case studies to illustrate factors that can affect the critical role that program evaluation plays in the community-based practice of community psychology. Each of these factors emerges from my on-the-ground, in-the-trenches, front-line experiences of working with community-based agencies and programs that rely on county, state, and/or federal funding, that is, public monies, or on local, state-based, or national foundations for private money. Extracted from these seven “lessons learned” are three principles that have emerged as guides for my work in the field of program evaluation. They are: (1) ensuring that the evaluation results are useful, (2) making sure the evaluation is simple and doable, and (3) evaluation efforts are congruent with the program efforts. The figure below highlights these three principles:

Finally, program evaluation serves as a critical part of the practice of community psychology, providing essential information for funding sources, and crucial feedback for those aiming to improve individuals’ quality of life and well-being. Those of us who work/practice in the community most assuredly value the consistencies and, at the same time, the idiosyncrasies of that work, as reflected in the seven takeaways and the illustrations of each. Those who are change agents or interventionists also intuitively or actually know the value of building assessments or measures into their change efforts from the beginning to identify both areas in need of improvement and areas of success. Using appropriate program evaluation strategies based on the three principles cited above will enhance the efficacy of community-based interventions.

From Theory to Practice Reflections and Questions

- Program evaluation plays an important, structural role in its contributions to the assessment of the intervention work of change agents, where community psychology practitioners and relevant stakeholders work together to design and implement needed community-based programs (O’Connor, 2021). What lens might a community psychologist bring to the table in a program evaluation? What lens would another psychologist bring (e.g. social psychologist or clinical psychologist)

- Describe why it is important when conducting program evaluations to analyze the data collected from an ecological level.

- What conceptions did you hold prior to reading this case story about program evaluations

References

Beauregard, C., Tremblay, J., Pomerleau, J., Simard, M., Bourgeois-Guerin, Lyke, C., Rousseau, C. (2020). Building communities in tense times: Fostering connectedness between cultures and generations through community arts. American Journal of Community Psychology, 65, 437-454. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12411

DaViera, A.L., Roy, A.L., Uriostegui, M., Fiesta, D. (2020). Safe spaces embedded in dangerous contexts: How Chicago youth navigate daily life and demonstrate resilience in high-crime neighborhoods. American Journal of Community Psychology, 66, 65-80. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12434

Goodkind, J.R., Bybee, D., Hess, J.M., Amer, S., Ndayisenga, M., Greene, R.N., Choe, R., Isakson, B., Baca, B., Pannah, M. (2020). Randomized controlled trial of a multilevel intervention to address social determinants of refugee mental health. American Journal of Community Psychology, 65, 272-289. https://doi-org.nl.idm.oclc.org/10.1002/ajcp.12418

Lin, E.S., Flanagan, S.K., Vargo, SM., Zaff, J.F., Margolius, M. (2020). The impact of comprehensive community initiatives on population-level child, youth, and family outcomes: A systematic review. American Journal of Community Psychology, 65, 479-503. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12398

Maleki, F.M., Massahikhaleghi, P., Tehrani-Banihasnemi, A., Davoudi, F. (2020). Community-based preventive interventions for depression and anxiety in women. Archives of Iranian Medicine, 23(3), 197-209.

O’Connor, B. (2013). From isolation to community: Exploratory study of a sense-of-community intervention. Journal of Community Psychology, 41(8), 973-991. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21587

O’Shaughnessy, B.R., & Greenwood, R.M. (2020). Empowering features and outcomes of homeless interventions: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. American Journal of Community Psychology, 66, 144-165. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12422

Shek, D.T.L., Ma, C.M.S, Law, M.Y.M., & Zhao, Z. (2017). Evaluation of a community-based positive youth development program or adolescents with greater psychosocial needs: Views of the program participants. International Journal of Disabilities and Human Development, 16(4), 387-393. DOI 10.1515/ijdhd-2017-7007

Stewart, K., & Townley, G. (2020). How far have we come? An integrative review of the current literature on sense of community and well-being. American Journal of Community Psychology, 66, 166-189. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12456

Suarez-Balcazar, Y. (2020). Meaningful engagement in research: Community residents as co-creators of knowledge. American Journal of Community Psychology, 66, 261-271. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12414

Wadsworth, M.E., McDonald, A., Jones, C.M., Ablkvist, J.A., Perzow, S.E.D., Tilghman-Osborne, E.M., Creavey, K., & Brelsford, G.M. (2020). Reducing the biological and psychological toxicity of poverty-related stress: Initial efficacy of the BaSICS intervention of early adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 65, 305-319. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12400

Feedback/Errata