6 Lessons from Conducting an Equity-Focused, Participatory Needs Assessment

Kyrah K. Brown, PhD, Susan M. Wolfe, PhD, Justin M. Henry, MPH, Claudy

Jean Pierre, BSPH, Tamaya Bailey, MSW, and Jerrise Smith

This case story focuses on the authors’ work to conduct a comprehensive Ryan White HIV/AIDS needs assessment in North Texas. We highlight three key issues from a community psychology perspective.

The Big Picture

In the United States, an estimated 1.2 million people are living with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Men who have sex with men (MSM) and bisexual men of color, African American heterosexual women, and Latina heterosexual women continue to be disproportionately impacted by HIV. For thirty years, service organizations funded by the Ryan White HIV/AIDS program have been mandated to conduct comprehensive needs assessments every three years to help planning councils develop and implement strategies to improve access, reduce barriers, and enhance service delivery and satisfaction. This case story focuses on the authors’ work to conduct a comprehensive Ryan White HIV/AIDS needs assessment in North Texas. We highlight three key issues from a community psychology perspective.

First, in most cases, previous needs assessments have consistently demonstrated needs and barriers influenced by structural or political forces; yet the service landscape largely focuses on first-order strategies whereby individual behaviors, knowledge and attitudes are the target of programs and services.

Second, consultants leading previous needs assessments in this community have rarely used participatory approaches which are known to enhance buy-in, trust, and participation, especially among people living with HIV who are further marginalized based on race/ethnicity and/or gender identity.

Third, previous needs assessments have failed to incorporate an equity perspective that includes the impact of sexism, homophobia, racism, and intersectionality on prevention and intervention.

About the Community or Big Picture Concerns

In the United States (U.S), an estimated 1.2 million people are living with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Although overall HIV rates have declined in the U.S., persistent disparities exist based on race/ethnicity, gender and gender identity, and sexual orientation. Black heterosexual women, transgender women of color, and others continue to be disproportionately impacted by HIV. For example, although Black people make up 13% of the U.S. population, 43% of U.S. adults living with HIV are Black and 42% of new HIV diagnoses are Black people. An estimated 14% of transgender women in the US are estimated to be living with HIV, for Black transgender women, the figure is 44% (Lancet, 2020).

Disparities persist within the HIV care system as well. For example, in the Dallas metropolitan area, 79% of people living with HIV were linked to care after diagnosis in 2018 (Wolfe & Brown, 2020). When disaggregated, fewer Black (76.3%) and Hispanic people (77.8%) were linked to care after diagnosis compared to White people (83.1%). In 2018, 72.9% of people living with HIV were retained in care, but lower retention rates were observed among Black people (68%), youth and young people (ages 13-24; 24-34), and people whose mode of transmission was intravenous drug use (67%). Retention in care is associated with viral suppression (i.e., the amount of HIV in the blood was at a very low level) and is an important determinant of health. Overall, 64% of people living with HIV in the Dallas metropolitan area were virally suppressed in 2018. Black (57%) and Hispanic (64%) were less likely to have viral suppression than White people (72%). Also, compared to men who have sex with men (66%), viral suppression was relatively lower among people whose mode of transmission was intravenous drug use (56%). Youth ages 13-24 (51%) and young adults ages 25-34 (57%) also had lower viral suppression compared to older adults and the overall population (Wolfe & Brown, 2020). Much of these disparities are attributable to system-wide inequities in access to health and behavioral health care (as well as gender-affirming care), housing stability, and economic stability (Lancet, 2020).

In this work, it is important to recognize that systems of oppression (i.e., racism, classism, transphobia, homophobia) operate in a mutually reinforcing manner to produce inequities in HIV risk, testing, infection, and mortality (McGibbon, 2012; Ford, 2017; Gee & Ford, 2011; Wilson et al., 2016). Structural racism is a system of oppression and is a key driver of persistent poverty or pay inequity, unequal educational attainment, mass incarceration, residential segregation, and housing instability. In the U.S., Black people are less likely to be prescribed pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), less likely to have access to healthcare, and underrepresented in clinical trials. Additionally, healthcare providers are less likely to discuss PrEP with Black patients. In addition, income inequality and socioeconomic deprivation are two key socioeconomic drivers for HIV diagnosis and transmission. The authors of a study (Ransome et al., 2016) found that income inequality and socioeconomic deprivation were associated with higher rates of late HIV diagnosis in unadjusted models. Black racial concentration robustly predicted late HIV diagnosis. Black residential segregation was positively correlated with HIV incidence. The white racial composition was among neighborhoods across quadrants of low-high inequality and HIV, neighborhoods with above 50% black racial concentration were in low inequity-high.

From a societal perspective, people living with HIV systematically experience disparate health and healthcare outcomes depending on their proximity to oppression and privilege (McGibbon, 2012). For example, in the U.S., Black men who have sex with men (MSM) are closer in proximity to systems of oppression based on race compared to white MSM; with white MSM systematically experience better health and health outcomes. Community psychologists have interrogated these systems by examining the historical narratives behind the HIV movement and the crediting of white gay men as the victors of the social and political response to the HIV epidemic (Wilson et al., 2016). Consequently, such narratives fail to acknowledge the diverse and intersectional identities (and experiences) of people living with HIV; and thus, these groups are further marginalized.

For thirty years, service organizations funded by the Ryan White HIV/AIDS program have been mandated to conduct comprehensive needs assessments every three years to help planning councils develop and implement strategies to improve access, reduce barriers, and enhance service delivery and satisfaction. Eligibility for Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program funding is based in part on the number of confirmed HIV/AIDS cases within a specified metropolitan area, which is characterized by a central urban area surrounded by other urban areas that work together economically or socially. The Dallas eligible metropolitan area includes eight counties with the city of Dallas representing the largest population of people living with diagnosed HIV infection.

The findings from a comprehensive needs assessment also helped to identify and address persistent health disparities in the population. In fact, the Ryan White HIV/AIDS program emphasizes the importance of focusing on high-priority populations, such as Black MSM, heterosexual Black women, and transgender men and women, in the needs assessments.

The needs assessment we describe in this chapter includes a seven-county area, although the largest share of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) in North Texas reside in only one of the seven counties (Dallas County). This is likely attributable to resource allocation, whereby most of the services and specialized health care are in the City of Dallas, with little or no HIV/AIDS specific services available in the outlying, rural counties. In fact, in 2018, 81% of people living with HIV resided in Dallas County (Wolfe & Brown, 2020). Further, the Pew Research Center found increasing income and racial segregation over the past three decades in the Dallas Metro Area, with most low income, predominantly non-white households located in the southern part of the city of Dallas, particularly south of Interstate 30. Most of the health care and other services for PLWHA are located north of Interstate 30.

Background of How We Came to Work with this Community Partner

Prior to receiving the contract to conduct the needs assessment, the community consultant (SMW) and academic partner (KKB), both trained community psychologists, had a history of strong relationships with organizations throughout the Dallas metropolitan area. In particular, the community consultant’s company is a woman-owned firm located in the Dallas metropolitan area. For over 10 years, her firm has partnered with organizations and foundations in the area to build their capacity for evaluation, program development, and coalition building. In addition to having conducted resource and needs assessments in other communities, the community consultant had a history working with Dallas County HHS and the Dallas County public hospital system.

In early 2019, Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program (RWHAP) issued a request for proposals (RFP) for their 2019 Comprehensive HIV/AIDS Needs Assessment. After the initial deadline passed with no proposal submissions, the community consultant was informed by a community colleague that the RFP deadline was extended and encouraged her to submit a proposal. The community consultant invited an academic partner (also trained in community psychology) at a local university (KKB) to collaborate and form the evaluation team.

The evaluation team consisted of the:

- community consultant as the lead,

- the academic partner,

- three student assistants (TB, JS, & CJP) who worked as paid project assistants, and

- over 15 trained undergraduate and graduate public health students who assisted with needs assessment data collection and data entry.

Evaluation Team and Positionality

The consultant (SMW) is a white, cisgender, heterosexual woman from a blue-collar, working-class background with a PhD. She has over 35 years of experience working with programs and systems change initiatives that are addressing health, education, and other racial and ethnic disparities. She explicitly recognizes her positionality and privilege as she engages in this work.

The academic partner (KKB) is a Black, cisgender, heterosexual woman from a middle-class background. She has a PhD and over 10 years of experience working in diverse community and organizational settings as well as academic expertise in health equity, racial and ethnic health disparities, and women’s health.

TB is a cis gender, heterosexual Black woman from a lower middle-class background. She has a Master’s in Social Work with a concentration in Mental Health and Substance Abuse. Her background includes research surrounding maternal child health and postpartum depression. She also has experience in community health and mental health working with individuals living with HIV/AIDS. She previously served for seven years in the United States Air Force.

JS is a Black, heterosexual woman from a working-class background. She is an Air Force Veteran with eight years of exemplary service. Her experience includes qualitative research in maternal and infant health, food deserts, PTSD in low-income communities, and drug and alcohol abuse among veterans that received a dishonorable discharge.

CJP is a Black, cisgender, heterosexual man from a middle-class background. He has a Bachelor of Science in Public Health and is currently pursuing his Master’s degree in Public Health. He has experience working with different populations including women’s health and people living with HIV/AIDS. He also works internationally to help women in Haiti to engage in healthy behavior to prevent pregnancy complications.

Collaborative Partners and Our Approach to this Work

Dallas County Health and Human Services (DCHHS) Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program and the Ryan White Planning Council (RWPC) commissioned this needs assessment project. Therefore, our evaluation team worked closely with RWPC as its primary collaborative partner, which is a community group consisting of 33 people living with HIV (PLWH), an HIV service provider representative, and other community members. Our evaluation team also worked closely with the RWPC Health Planner (JMH) who shares responsibility with the RWPC to oversee the planning and implementation of the needs assessment. The RWPC’s mission is to optimize the health and well-being of people living with HIV/AIDS through coordination, evaluation, and continuous planning to improve the North Texas regional system of medical, supportive, and prevention services. Our evaluation team met on a bi-weekly basis with the RWPC Health Planner and on a routine basis with the RWPC committee members based on their existing meeting schedule. Although not directly involved in the planning, there were also more than 60 individuals (many of whom were PLWH) and HIV health and service organizations in the care continuum who assisted with implementation in many ways including scheduling of data collection activities, serving as points-of-contact for data collection activities, and sharing information about the needs assessment.

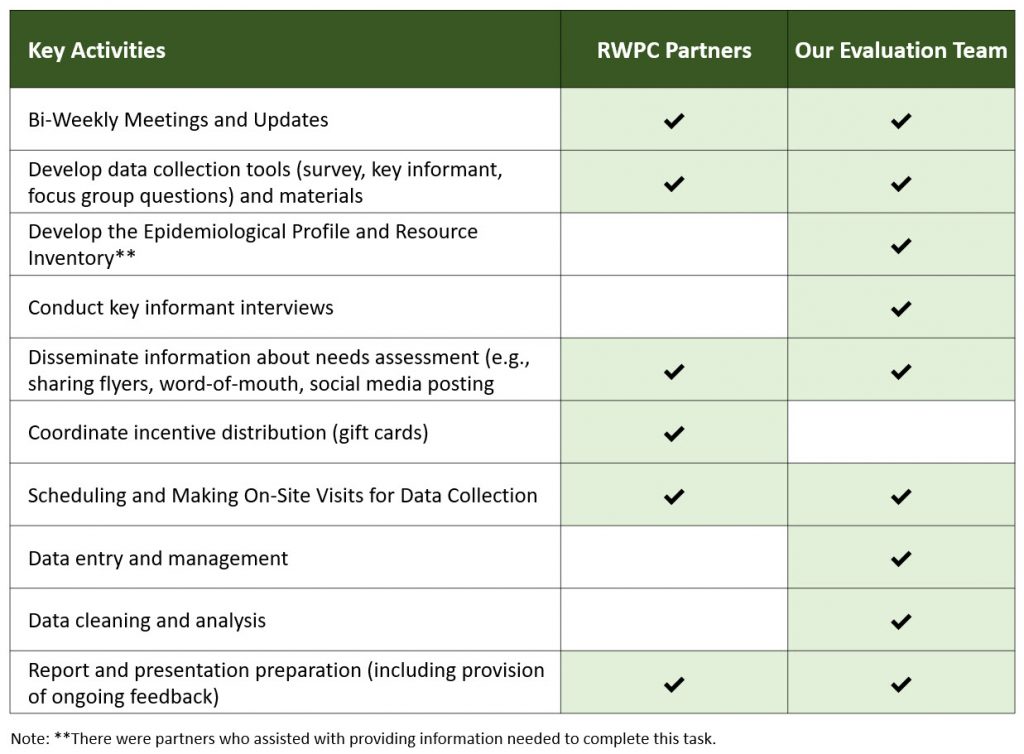

Through initial discussions, our evaluation team and the RWPC determined that a participatory evaluation approach, guided by the evaluation team, was most appropriate for this project. A participatory evaluation approach ensures that community partners are involved in a collaborative and meaningful way throughout every phase of the needs assessment. Our evaluation team did discuss the importance of an empowerment approach whereby community members and RWPC members could be trained and take ownership of needs assessment activities. However, the final decision for a participatory approach was made because the amount of time to complete the project was shortened due to system delays, the implications of not meeting the timeline (e.g., loss of federal funding), the RWPC’s desire to be engaged in the planning and implementation in such a way that did not exceed their own capacity, and the fact that our evaluation team was hired to ensure the completion of the work as contracted. The RWPC was empowered in that they had the authority to fire us at any time during the process if we did not provide what they needed, and they had oversight authority for our work as well. We discuss the nature of this participatory approach later in this case study (also see Table 2).

During the process of gathering background information in preparation for this collaborative work, our evaluation team reviewed the comprehensive HIV/AIDS needs assessment reports from the previous cycle (Dallas County Department of Health and Human Services, 2017). We identified three key shortcomings from a community psychology perspective and tailored our approach to addressing them.

First, the prior needs assessment failed to incorporate a health equity perspective, which involves understanding and acting on the relationships between social determinants of health, health inequities, and health disparities (or population-based differences in health outcomes). Health equity requires a justice orientation and commitment to addressing avoidable inequalities, historical and contemporary injustices, and the elimination of health and healthcare disparities. Community health needs assessments that lack a health equity perspective can unintentionally increase inequities (which result in greater disparities). Community health needs assessments are used to guide community action; and when the factors that drive inequities are left unacknowledged, this can inadvertently lead to them being unaddressed. Consequently, our evaluation team applied a health equity lens by:

- supporting honest dialogue with collaborative partners about the community’s history and systems of oppression that marginalize various groups of people living with HIV,

- engaging in informal conversations with marginalized consumers (e.g., Transpeople of color, heterosexual women) to ensure that their voices were included across multiple data sources and the final report, and

- continuously framing the needs assessment within a health equity lens when engaging in conversations with providers and HIV service organizations.

Second, the prior needs assessment failed to frame the identified community assets and needs from an intersectional perspective. An intersectionality perspective holds that people’s social and political identities (and the socially constructed meanings tied to those identities) interact to create contextualized experiences of oppression and privilege. This perspective holds that people’s intersectional experience is “greater than the sum” of racism, sexism, classism, and other forms of oppression (Crenshaw, 1989). Accordingly, our evaluation team was committed to preparing a report and community presentation that explicitly considered how the lived experiences of people living with HIV is shaped by their proximity to oppression and privilege along the lines of health status, (dis)ability, gender identity, and expression, race, class, sexuality, language and so on. We used the available data to identify and report the varying needs of sub-populations of people living with HIV and provided tailored recommendations for these groups.

For example, we made sure to triangulate focus group data and consumer survey data to create an infographic of perceived assets and needs among the following priority sub-populations:

- Black men who have sex with men,

- cisgender heterosexual Black women,

- Latina/o/x people,

- Transgender people,

- youth and millennials,

- senior adults, and

- rural residents.

This approach was appreciated because early on in the process, we were informed by heterosexual Black women as well as Transgender women and advocates about concerns related to being unheard and overlooked in broader HIV prevention efforts.

Third, the prior needs assessment did document service needs and barriers shaped by structural and political factors. However, the discussion of these factors was perfunctory and recommendations focused heavily on first-order rather than second-order changes. There was also no mention of structural oppression and its contribution to the disparities identified across populations. This is problematic because improvements in HIV prevention and treatment cannot be accomplished by focusing exclusively on the individual level (i.e., providers and consumers). There is a need for more enduring solutions situated in systems and policy. The social-ecological perspective recognizes individuals as embedded within larger social contexts and considers the complex interplay of individual, interpersonal, community, institutional, and societal factors (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Lewin, 1936; Kelly, 1966). Accordingly, our team applied this perspective to frame the community assets and needs from the needs assessment. This was important because, in the HIV/AIDS health and social service system, the biomedical model of illness remains a predominant paradigm that often reinforces victim-blaming and fails to consider how institutions and systems shape health risk and health behaviors. It was important to our team to apply a social-ecological perspective to help us place more emphasis on the policies and systems beyond the individual that impact people living with HIV. Therefore, during the data analysis and reporting phase, we organized the results regarding assets and needs into three multi-level categories: individual/interpersonal level, socio-economic level, and systems and structural level. We also made sure that our recommendations were organized in this matter to assist the community partners with system-wide action planning.

Description of Project

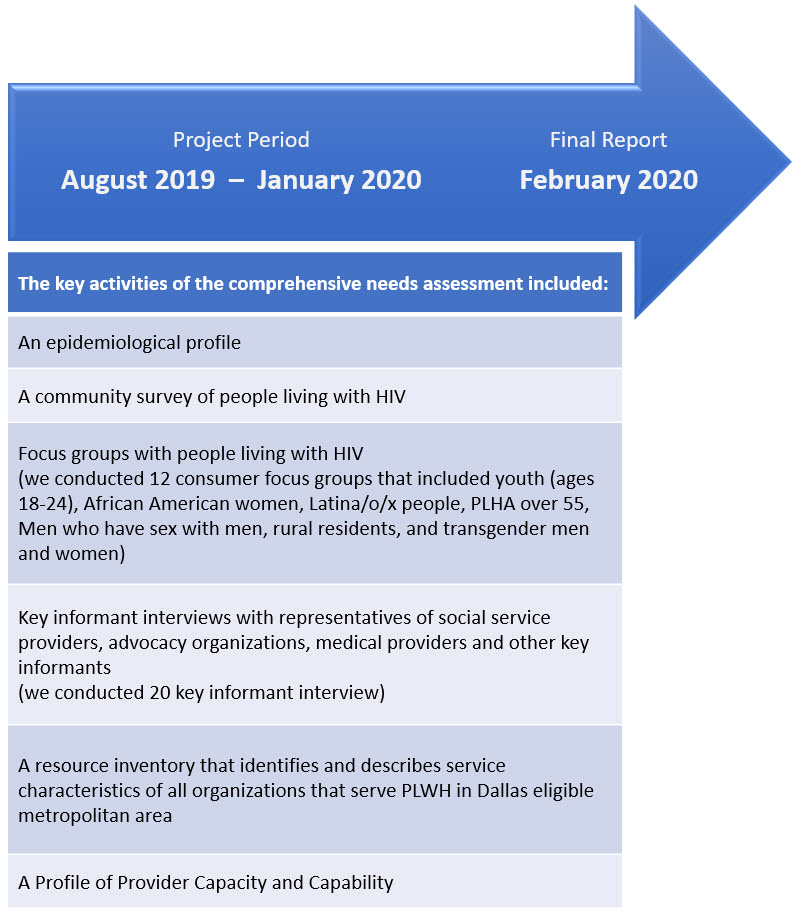

At the beginning of August 2019, our evaluation team was awarded the contract to conduct the comprehensive HIV/AIDS Needs Assessment. The project period was August 2019 to January 2020 with the final report due in early February 2020. The image below highlights the report:

Based on the scope of work, the project period for the comprehensive needs assessment needed to be at least 15 months. Our evaluation team communicated initial concerns about the timeline and the limitations of completing this amount of work within such a tight timeline. Under different circumstances, we would recommend re-scoping the work; however, our team agreed to take the project on because (1) the RWPC had prior experience and competence in planning and implementing a comprehensive needs assessment, (2) our evaluation team had the human and material resources needed to accomplish the task, and (3) our participatory approach allowed for diffusion of some planning and implementation activities needed to get the work done.

Initial Planning Phase

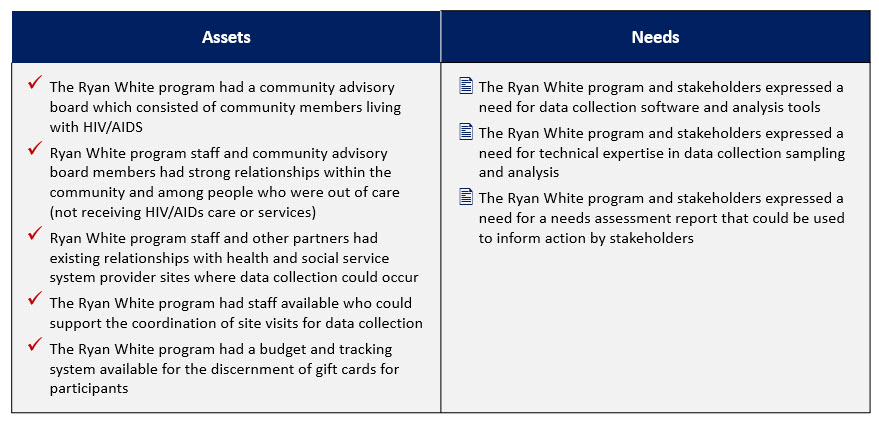

Our first step was to convene the RWPC and other community partners to define roles for the project. During the planning phase of the HIV/AIDS needs assessment, we met with the RWPC, our primary collaborative partners, to identify their needs and assets. Our meetings focused on discussing the following questions: What did you dislike about the product or process of the last needs assessments? What does a successful needs assessment look like? How do you hope to be able to use the information from this needs assessment? What human, technical, or financial resources do you currently have that may help contribute to the success of the needs assessment? What additional human, technical, or financial resources are needed to make this needs assessment successful?

Our biggest surprise during this process was when we learned that the prior consultants, who were located in another state, had relied upon the RWPC and service providers to collect all of the needs assessment data. This included scheduling data collection activities, administering surveys at local sites, conducting the focus groups at sites, manually entering data from paper surveys. This process was problematic because it placed an undue burden on the community partners, which took away time from service and care provision. As we discussed assets and needs amongst ourselves, our evaluation team assured the community partners that our team would handle the ‘heavy lifting’ with these activities while emphasizing that they could be as involved in the process to the extent that they were able.

Based on discussions around these questions, our evaluation team was able to identify pertinent information about partners’ perceived assets and needs which would help inform the planning and implementation of the needs assessment (see Table 1). The benefit of identifying assets and needs among community partners before the start of the needs assessment was that everyone on the team understood the strength that they brought to the team and was clear about what role they had on the project. After these initial discussions, our team drafted a document that outlined each partner’s role on the project (see Table 1).

Table 1. Community Partner Assets and Needs

Our community partners, the RWPC and the RWPC Health Planner had prior experience with planning and implementing needs assessments. They developed the survey questions and the focus group questions. Our team worked collaboratively with them to make modifications to the length, added skip-logic instructions, created an online version of the survey, and provided a Spanish version of the instruments and flyers. All final changes to the data collection tool and recruitment material were reviewed and approved by the collaborative partners before data collection started. The implementation of the needs assessment was characterized by our evaluation team and the community partners completing activities in a complementary manner (e.g., RWPC would help schedule and recruit people for focus groups; RWPC partners would provide trusted interpreters for data collection activities) and a collaborative manner (e.g., both RWPC partners and members of our evaluation team would set up at local sites to recruit for surveys or to conduct focus groups). Although the evaluation team took the lead on data analysis and preparing the report, the RWPC was involved via progress meetings to review the information and provide feedback along the way. Table 2 below provides a breakdown of the roles and responsibilities each of the partners played.

Table 2. Approach to Key Needs Assessment Activities

During this comprehensive needs assessment, we sought to understand the diverse perspectives within the communities of people living with HIV by working closely with the local Ryan White planning council whose members included consumers. With any needs assessment, prior to starting data collection, it is important to ensure everyone shares common definitions of key terms. In this instance, we needed a clear definition and conceptualization of what we meant by “assets” and “needs.”

Defining and Conceptualizing Assets and Needs

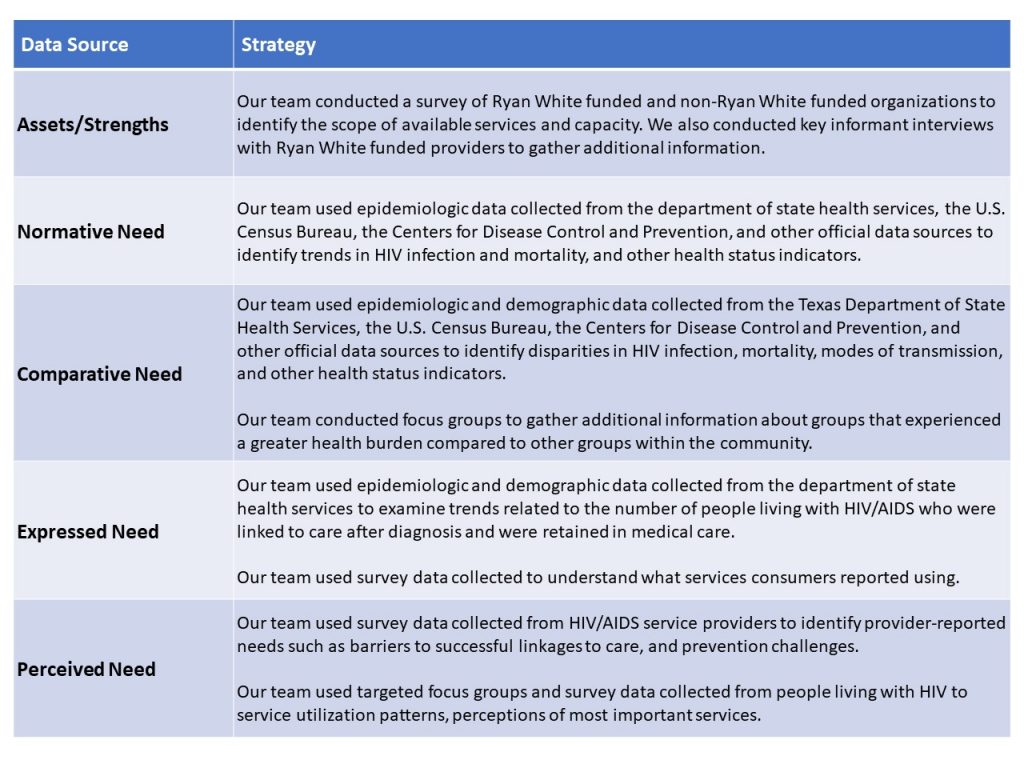

The field of community psychology emphasizes the importance of adopting an asset-based perspective, which means building on existing skills or resources rather than fixating on community deficits. Accordingly, we were intentional about balancing the discussion of community assets and needs in the HIV/AIDS needs assessment. To ensure a comprehensive understanding of need, our team incorporated Bradshaw’s taxonomy of need [13]. According to this taxonomy, need may be defined based on (1) the extent to which groups within a community meet a standard of health that has been established by experts (normative need), (2) the extent to which one group experiences a greater health burden compared to another group within a community (comparative need), (3) the extent to which groups within a community use (or do not use) available services or programs (expressed need), and (4) the explicit input from groups in the community who have a related lived experience (perceived need). For the HIV/AIDS needs assessment, our team collected a variety of primary and secondary data sources to capture the community assets and needs (see Table 3).

Table 3. Data Sources and Strategies

Conducting a Consumer Survey

The consumer survey was designed to collect information about socio-demographics, health history, medical care, health behaviors, intimate relationships, use of prevention and intervention services, and barriers to services. A cover sheet explained the purpose of the survey, risks and benefits, planned data uses, and consent.

We calculated the sample size based on the current total HIV prevalence for the Dallas Eligible Metropolitan Area (2018), with a 95% confidence interval at a 5% margin of error. Eligibility criteria included individuals who were age 18 years or older, live in one of the Dallas EMA/HSDA counties, were diagnosed with HIV and/or AIDS, and have not already completed the survey. Efforts were taken to over-sample in rural locations, youth (via social media), and those out-of-care. However, the two-month timeframe for data collection presented a key challenge.

We administered consumer surveys at pre-scheduled sessions at Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program provider sites, housing facilities, and specific community locations and organizations. Staff contacts at each location were responsible for session promotion and participant recruitment. Out-of-care consumers were recruited through flyers, word-of-mouth, social media, and staff promotion. Surveys were self-administered in English and Spanish, with staff and interns available for verbal interviewing for individuals who needed assistance. There were also bilingual staff and/or interns who provided verbal interviewing when needed. Members of the evaluation team and RWPC administered surveys asked each survey participant if they would prefer to have the questions read to them or to complete the survey on their own. This ensured that individuals with literacy challenges or visual impairments would be able to participate without having to disclose their disabilities. In fact, during data collection, there were many instances of our teams assisting consumers with their surveys in this manner. Our evaluation team consisted of individuals who were fluent in English, Spanish, and French, and French-Creole. Participation was voluntary, anonymous, and monetarily incentivized ($15); and respondents were advised of these conditions verbally and in writing. Most surveys were completed in 20 to 30 minutes. Surveys were received on-site by trained staff, interns, and the evaluation team for completion and translation of written comments. Completed surveys were logged into a centralized survey database. Online survey participants were provided with an auto-generated unique code at the end of the completed survey. Participants were instructed to contact the Ryan White Planning Council Health Planner to provide the code and arrange a time to retrieve their gift cards.

In total, 421 consumer surveys were collected from December 2019 to January 2020 during 10 sessions at six survey sites (including one rural location and one housing facility). The final sample size was 392 after eliminating ineligible cases.

A major limitation was that we used a convenience sampling strategy, rather than random sampling, for this portion of the needs assessment. As a result, the majority of the sample represents PLWHA in urban settings (Dallas County) and in care receiving Ryan White Program services. This sample is less representative of youth (18 to 24-year-olds), transgender women and men, heterosexual women, individuals experiencing homelessness, and individuals living in rural settings. A longer project timeline would have allowed the team to overcome these challenges. For example, our team had on-site visits in several rural communities where we would spend several hours set up to recruit individuals. But, those facilities had so few walk-in consumers that more visits would have been needed to recruit enough people from those communities.

Creating an Inventory of HIV Service Providers and Assessing Service Capacity

To conduct the inventory of HIV service providers, the evaluation team trained a group of five graduate public health students to generate a resource inventory of agencies serving people living with HIV and/or AIDS without Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program funding. These students were required to engage in this project for their graduate course and were able to fulfill their course requirements by completing this project. Using the resource inventory template, students performed internet searches and made phone calls to organizations to verify key information. The student team used a snowball sampling technique to identify additional organizations.

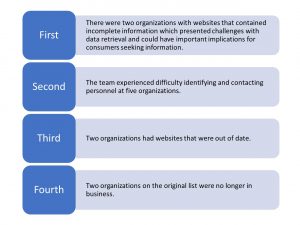

There were four key challenges during data collection: (1) two organizations with websites that contained incomplete information, (2) difficulty identifying and contacting personnel at five organizations, (3) two organizations had websites that were out of date, and (4) two organizations on the original list were no longer in business. The image below highlights these challenges.

The Ryan White Planning Council Health Planner provided the evaluation team with a list of nine organizations funded by the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program along with contact information. The Ryan White HIV Service Provider Capacity Survey was administered to these nine organizations. Eight of the nine organizations (88%) completed the survey. Once data collection was complete, services information from the non-Ryan White funded organizations was combined with services information obtained from the provider capacity survey.

The evaluation team experienced some challenges with obtaining responses from providers. It is possible that the nature of some of the questions (e.g., number of unduplicated clients served by service type) posed a challenge for respondents which delayed survey completion. Additionally, it is possible that some providers interpreted certain questions differently than others. For the next administration of the survey, the evaluation team will address survey question specificity and clarity. Also, the evaluation team used the provider capacity survey from previous years. This version of the survey does not capture detailed information about service capacity. Therefore, steps will be taken to ensure that the survey is designed to address this topic.

Key Informant Surveys

The Key Informant Surveys were conducted by the community consultant. The RWPC provided the community consultant with a list of organizations, contact names, and contact information for individuals who play a key role in the development and provision of services to PLWHA in the Dallas EMA. Organizations represented housing services, health care services, mental health services, children’s health services, consumers, policy and advocacy services, transgender services, and other service providers serving PLWHA in the Dallas EMA. Nineteen respondents served Dallas County and one respondent served a rural area.

Email invitations were sent to individuals from 27 different organizations requesting their participation. Recipients were asked to click on a link to Sign-Up Genius to select a date and time slot to schedule their interview. Follow-up invitations were sent to non-respondents after the sign-up deadline passed. Twenty-three individuals responded and signed up to be interviewed. One individual was unable to participate at her designated time due to an unforeseen event; one had to cancel because of a conflict and did not reschedule, and another did not show at the scheduled time. The final number of interviews was 20 key informants.

The interview was conducted using a semi-structured interview protocol via Zoom conferencing technology on the computer or telephone. All Key Informants agreed to have their interviews recorded. Interviews averaged one hour. Three interviewees were unable to complete the entire interview because of scheduling conflicts or other time limitations.

We also prepared the focus group and key informant interview protocols using questions that were developed by the RWPC. Our goal was to ensure that we answered the questions they needed to be answered and obtained the information they needed for planning.

Consumer Focus Groups

We conducted 12 in-depth focus groups with various groups including transgender individuals, youth (18-24), Black heterosexual women, aging MSM, MSM of color, and Latina/o/x people to gain an understanding of their experiences and worldviews. A major gap in previous work has been a lack of participatory approaches, insufficient attention to African American and Latina heterosexual women and transgender individuals. For example, there are strong sentiments among African American women against being categorized as “women of color”. Also, transgender individuals, especially transgender people of color, can be especially marginalized within the LGBTQIA+ community. Our partners provided an interpreter for the groups with Latina/o/x people since many spoke Spanish as their first or primary language. At the time this needs assessment was conducted, a number of Black transgender women had been murdered in this community, and therefore safety was a concern. Our team honored the need expressed by the Black transgender community to protect itself from the threats of structural violence and accepted that we would not be able to recruit many Black transgender women for focus groups. Although not a planned data collection strategy, our team did have informal conversations with some transgender women of color and advocates for the transgender community informally in an effort to capture their voices in this process. This reality illustrates how systems of oppression shape marginalized communities’ feelings of safety and ability to share their voices on matters that directly impact them.

To demonstrate respect for this community we were careful about language and dynamics within the community of PLWHA. We made sure to listen carefully to program staff and consumers about the language and focus that they desired for this needs assessment. Most importantly, we did not go in using our Dr. titles, nor did we position ourselves as “experts.” We conducted focus groups at sites chosen by the group and at times that were most convenient for them, mostly during the evenings. Our partners provided snacks or meals (depending on the timing and the group) and we stayed to socialize when the group invited us.

Five of the focus groups were conducted by the Care Coordination Ad Hoc Committee or a researcher from the local public hospital system before the consultants were retained and the remaining seven focus groups were conducted by our team. All focus groups used a standard, semi-structured protocol. Eleven of the 12 focus groups were recorded. Participants were asked if they consented to record and one participant in one group asked that the focus group not be recorded. Participants were asked to sign an informed consent form and each participant received a gift card as compensation for their time and input. All focus groups were arranged by the RWPC in collaboration with service providers.

As mentioned earlier, one of the focus groups consisted of transgender men and women. The team member who facilitated the group was a heterosexual, white woman in her 60’s. The facilitator built trust and comfort in several ways.

First, the group was arranged by a trusted health care provider in a space that was familiar to the group.

Second, the facilitator arrived early which offered an opportunity to engage in casual conversations with participants who arrived early. One was a transgender woman of a similar age, well-known and respected within the community, who had been an activist for the transgender community for many years. The facilitator enjoyed an opportunity to hear of the history of activism and the methods that had been employed, in addition to the rich stories that were shared. By the time the remaining three participants arrived, she had built rapport and trust with this key individual.

Third, the facilitator had many years of experience conducting such groups and interviewing individuals that were different than herself. She has developed the ability to listen carefully and a level of comfort with difficult conversations.

When the focus group was completed, she shared a meal with the participants and continued with more casual and social conversations about topics such as hobbies, jobs, and food.

Outcomes or Impact

Despite the challenges encountered during this needs assessment, we were able to successfully complete it on time. In alignment with our focus on health equity, we wanted to ensure that the needs assessment results were presented in a manner that was equitable so that anyone from the general community could consume the information. We accomplished this by delivering a user-focused needs assessment report that was informed by design best practices. During early conversations, our collaborative partners expressed their desire for a report that was easy to understand and navigate; and one that could be used to effectively inform action. Our team studied prior HIV/AIDS needs assessments completed by different consultants and reviewed examples from other communities. Our team initially planned to apply Stephanie Evergreen’s 1-3-25 reporting model wherein reports consist of a one-page handout, a three-page executive summary, a 25-page report, and appendices that include more detailed information (i.e., description of the methodology, larger tables, and figures, etc.). While our team was unable to limit the report to 25-pages, we did limit it to 80 pages (162 pages including references and appendices). This was in stark contrast to prior needs assessments which had page counts that ranged from 300 to 400 pages in total.

Despite the challenges encountered during this needs assessment, we were able to successfully complete it on time. In alignment with our focus on health equity, we wanted to ensure that the needs assessment results were presented in a manner that was equitable so that anyone from the general community could consume the information. We accomplished this by delivering a user-focused needs assessment report that was informed by design best practices. During early conversations, our collaborative partners expressed their desire for a report that was easy to understand and navigate; and one that could be used to effectively inform action. Our team studied prior HIV/AIDS needs assessments completed by different consultants and reviewed examples from other communities. Our team initially planned to apply Stephanie Evergreen’s 1-3-25 reporting model wherein reports consist of a one-page handout, a three-page executive summary, a 25-page report, and appendices that include more detailed information (i.e., description of the methodology, larger tables, and figures, etc.). While our team was unable to limit the report to 25-pages, we did limit it to 80 pages (162 pages including references and appendices). This was in stark contrast to prior needs assessments which had page counts that ranged from 300 to 400 pages in total.

We also divided the 80 pages into sections using additional design principles to facilitate easier reading and navigation. For example, we color coded sections so that headings, icons, and graphs within each section were the same color. We minimized text to the extent possible and used visual representations such as infographics and graphs wherever possible. We de-cluttered graphs as much as possible so results from quantitative data were easily digested. We also used data visualization design principles to create and present a presentation to community members. We created a presentation that showed easily interpreted graphs and key findings.

Finally, a student member of our team was producing Infographics to share with community members, but this work was disrupted when the student contracted COVID-19 and her recovery period went beyond the time period for this project. However, as of January 2021, our team is working to complete the infographics in collaboration with the RWPC partners.

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly disrupted action planning and community engagement activities based on the needs assessment. At this point, we are not able to necessarily assess the longer-term impact of the needs assessment. However, as of March 2021, the RWPC is preparing to engage in data-driven action planning using the data and recommendations provided in the needs assessment report. Also, our team has maintained a relationship with the RWPC partners through ongoing communication, and hopefully, partnership in future needs assessment cycles.

The key findings and conclusions presented in this needs assessment were written to guide solutions targeting structural change and to address disparities at a systemic level. We described needs in a way that put the onus on the health care and service providers to make changes to improve access and availability, as well as to decrease stigma within healthcare systems and communities and to reduce other systemic barriers. We avoided describing our findings in ways that would suggest individual-focused interventions such as educating the PLWHA or changing their behaviors in some ways.

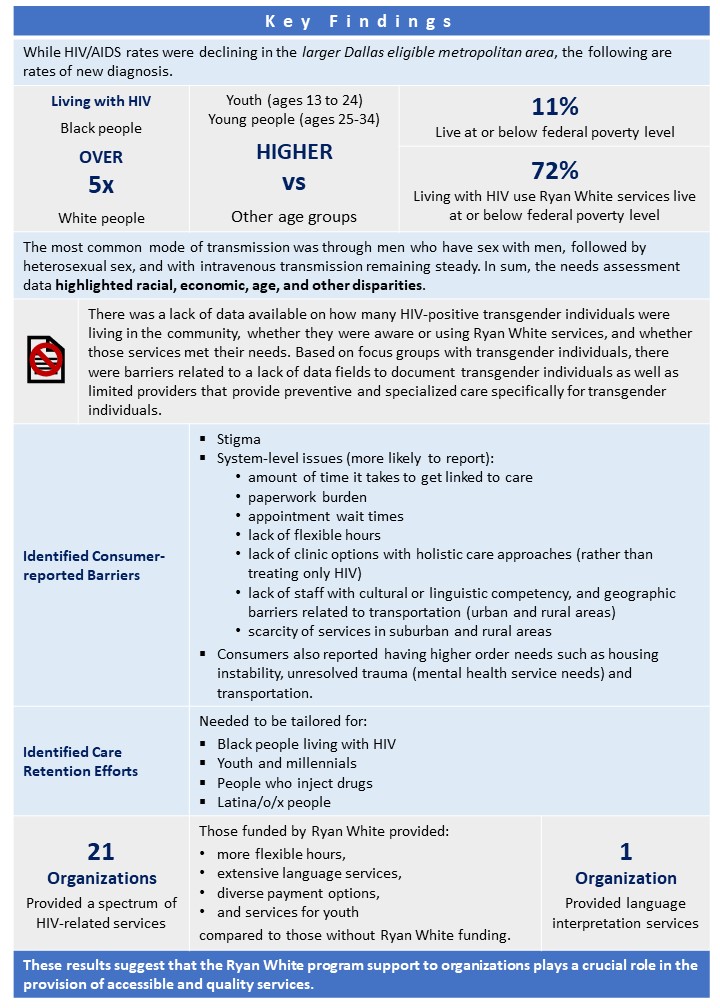

In terms of intermediate impacts, the needs assessment was effective to identify key findings that will help to guide further system-wide action planning. More information about the needs assessment is publicly available (Wolfe & Brown, 2020), we will share that the needs assessment did reveal the following key findings:

Lessons Learned

It is important to recognize that when community organizations such as local health departments commission the funding for projects they determine the timelines, plans, and resources. The Community Psychologist has to adhere to the designated timelines, resources, and plans. Our case study of this work has broader implications that can advance interdisciplinary work in community psychology and public health. Based on our work, we recommend that community psychologists conducting needs assessments (or other community-based evaluative work) advocate for longer timeframes if possible, to employ participatory and empowerment approaches and to build trusting relationships. There is a responsibility to educate communities about the time and resources that may be needed to undertake such work in a way that is truly inclusive.

The needs assessment covered a vast target area—much of it rural and without many resources or other centralized organizations where the target populations would be found. Additional time was needed to develop strategies and identify avenues to reach more PLWHA in the rural areas via surveys and focus groups.

It is also important to go beyond singular categories and recognize the role intersectionality impacts on needs and incorporate it into the data collection plan. As an example, if we had simply looked at males as a group, we would have missed all the unique needs of gay Black males, gay and straight Hispanic males, transgender individuals, and adolescent males.

We recognized the importance of acknowledging our own positionality as PhDs. The education level of our partners and the focal population varied widely. Even though the members of the RWPC had the authority to delegate responsibilities and even fire us, we still need to acknowledge the perception of the “expert” power we hold in this society. Additionally, the consultant is white. In the past, we relied on being “culturally competent” and more recently on exercising “cultural humility,” and this is insufficient. As a white heterosexual woman working in LGBTQIA+ communities of color and Black communities, deep reflection and additional work was required. This includes developing a deep understanding of concepts that include white privilege and white fragility, heterosexual privilege, anti-racism, and the impact colonization practices have had on different communities. It also requires ongoing, consistent reflection of what this means, and how, as a white person, the consultant may be (even unintentionally) upholding systemic racism and supporting oppressive systems. Most importantly, it requires recognition that this learning and reflection isn’t one-and-done. It is ongoing and must be persistent as no matter how “woke” we may be, we are all capable of saying or supporting racism, heterosexism, and other forms of oppression. We need to be ready to be called out, and when we are, acknowledge what we have said or done.

We also learned about the need to engage with and be present in the focal communities. This includes a need to spend more time in rural, outlying communities where LGBTQIA+ and HIV-positive individuals who need Ryan White services are not easily identified. There was little information obtained from six of the seven counties for this needs assessment. We were unsure whether it was because most of those who are affected by HIV or HIV positive reside in urban areas that are closer to services, or if the individuals are residing in rural areas, but remain hidden because of the stigma of HIV or being LGBTQIA+.

Recommendations

Be ready to start where the community is and adjust expectations to what is, not what should be in an ideal world. This project had a limited timeline which required our team to be less participative than desirable. We did not have time to pilot instruments and test strategies and had to hit the ground running with what we had. The budget was also limited which required that we find the best way to stretch the resources that were available.

Work with partners to teach them how they can get better results by engaging the consultant earlier. Spent time clearly defining roles and responsibilities. Provide partners with adequate resources so they are not overly burdened by adding needs assessment tasks to their already busy schedules.

Partner with community members and community-based organizations to reach populations that may be otherwise inaccessible. Consider the role of intersectionality when you are thinking of the different populations you need to reach. We found substantial differences between White and Black gay men and Black men and women in regard to needs and accessibility of assets, demonstrating that identifying by a single category will yield insufficient and potentially misleading results.

Ensure there are resources for translation services for surveys and to conduct focus groups and interviews. The prior needs assessment consumer survey was translated by a Spanish-speaking staff member at one of the partner organizations. RWPC members reported that it had not worked well because the individual had translated using a local dialect rather than a universally understood standard Spanish language. It is important when selecting translation services that they are professional services with linguistic and cultural translation expertise.

Needs and Resources as Participatory Research Projects

Community needs and resources assessments have many uses across community psychology practice. They are frequently requirements of funders and the Affordable Care Act and produce information that is useful for planning and writing grant applications. They are also useful for identifying policy needs and developing policies to meet them. By focusing on disparities and inequity, they can also support anti-racism and racial justice initiatives. Community psychologists are specifically skilled at participatory methods. The participatory process ensures higher quality results. Consumers know how to best reach the focal population, can provide endorsements that help to build trust, and provide expert advice for everything from what questions to ask to how to word the questions so they are understandable.

This, and the majority of needs and resource assessments require interaction with multiple races, ethnicities, and cultures. Cultural humility ensures that questions are appropriate to the focal population; that participants are not subjected to macroaggressions and other discomfort or potentially traumatizing treatment; and that results are interpreted accurately. Additionally, community psychologists must be ready and willing to serve as advocates by consistently identifying and calling out racism, homophobia, coloniality, and other behaviors and practices that support oppressive structures. Doing so requires prior introspection and acknowledgment of their own positionality.

Looking Forward

In summary, needs and resources such as the one presented here present opportunities for community psychologists to conduct meaningful work that has potential for impact. The data gathered will be used as the basis for planning services in this community for PLWHA for the next three years while ensuring that the needs of specific groups are considered. We recommended that the RWPC retain a consultant and begin the work at least a year before the report is due, ideally 15-18 months before. With more time we would have been able to increase data collection efforts, engage graduate and undergraduate student interns, create course projects to provide more meaningful evaluation experiences and make more connections to generate a more representative sample.

Conclusion

Community psychologists work in a number of areas in the community, where many work within the research evaluation or program evaluation field. Organizations and companies call on community psychologists in this area because they have been trained to see through a lens of co-creating health and wellness together with others than being the expert in the space. With this framework community psychologists hold space for difference and play integral roles in the continuation of fostering and nurturing community resilience and healing.

From Theory to Practice Reflections and Questions

- In this case study, Brown et al. (2021) shared the importance of recognizing that systems of oppression (i.e., racism, classism, transphobia, homophobia) operate in a mutually reinforcing manner to produce inequities in HIV risk, testing, infection, and mortality (McGibbon, 2012; Ford, 2017; Gee & Ford, 2011; Wilson et al., 2016). When you consider this statement, share with others what immediately comes up for you.

- How, if at all, did this case story challenge your beliefs or thinking about people living with HIV or programs serving them?

- As you think through the importance of research or program evaluations, what new considerations will you take away from this case story?

References

Bradshaw, J. (1972). Taxonomy of social need. In: McLachlan, Gordon, (ed.) Problems and progress in medical care: essays on current research, 7th series (pp. 71-82), Oxford University Press.

Bronfenbrenner U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Harvard University Press.

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 139-67

Dallas County Department of Health and Human Services. (2017). 2016 Comprehensive HIV/AIDS Needs Assessment. A report prepared for Dallas County Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program. Retrieved from: https://www.dallascounty.org/Assets/uploads/docs/rwpc/2016_Comprehensive_HIVAIDS_Needs_Assessment_FINAL.pdf

Ford, C.L. (2017). Notions of Blackness in the context of HIV/AIDS disparities and research. The Black Scholar, 47(4), 18-31. https://doi.org/10.1080/00064246.2017.1368064

Gee, G.C. & Ford, C.L. (2011). Structural racism and health inequities: Old issues, new directions. Du Bois Review, 8(1), 115-132. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742058X11000130

Kelly, J.G. (1966). Ecological constraints on mental health services. American Psychologist, 21(6), 535-539. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0023598

Lancet (2020). Racial inequities in HIV. www.thelancet.com/hiv, 7, e449. Accessed on March 24, 2021 at https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanhiv/article/PIIS2352-3018(20)30173-9/fulltext

Lewin, K. (1936). Principles of topological psychology. (F. Heider & G.M. Heider, Trans.). McGraw-Hill.

McGibbon, E. (Ed). (2012). Oppression: a social determinant of health. Fernwood Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1037/10019-000.

Ransome, Y., Kawachi, I., Braunstein, S., & Nash, D. (2016). Structural inequalities drive late HIV diagnosis: The role of black racial concentration, income inequality, socioeconomic deprivation, and HIV testing, Health Place, 42, 148-158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.09.004

Wilson, C.L. Flicker, S. Restoule, J.P. and Furman. E. (2016). Narratives of resistance: (Re) Telling the story of the HIV/AIDS movement – Because the lives and legacies of Black, Indigenous, and people of colour communities depend on it. Health Tomorrow: Interdisciplinarity and Internationality Journal. 4(1): 1-35).

Wolfe, S.M. & Brown, K.K. (2020). Ryan White Planning Council of the Dallas Area 2019 Comprehensive HIV/AIDS Needs Assessment [A Report]. Dallas County Health and Human Services, Dallas, TX.

Feedback/Errata