4 Better Together: Creating Alternative Settings to Reduce Conflict Among Youth in Lebanon

Ramy Barhouche

This case story illustrates community psychology in action within the region of Lebanon, where a collaborative partnership worked to create alternative settings for youth to reduce conflict.

The Big Picture

Community psychology in action can be seen through program implementation by Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs – Nonprofits) and Civil Society in much of the international community. There are two main broad subcategories of NGOs: Humanitarian Aid and International Development. Humanitarian Aid responds to an incident or event (e.g., conflict, natural disaster, poverty, or mass human displacement) and focuses on short-term disaster relief and meeting the immediate needs of the impacted communities. However, these services often take much longer periods than expected due to systemic dysfunctions. International Development programs, on the other hand, respond to long-term systematic problems and focus mainly on economic, social, and political development. It does so through human rights, diplomacy, and advocacy programs; as well as, economic, infrastructure, and capacity development. Both fields, along with others, often are implemented interchangeably and are impacted by and impact local realities.

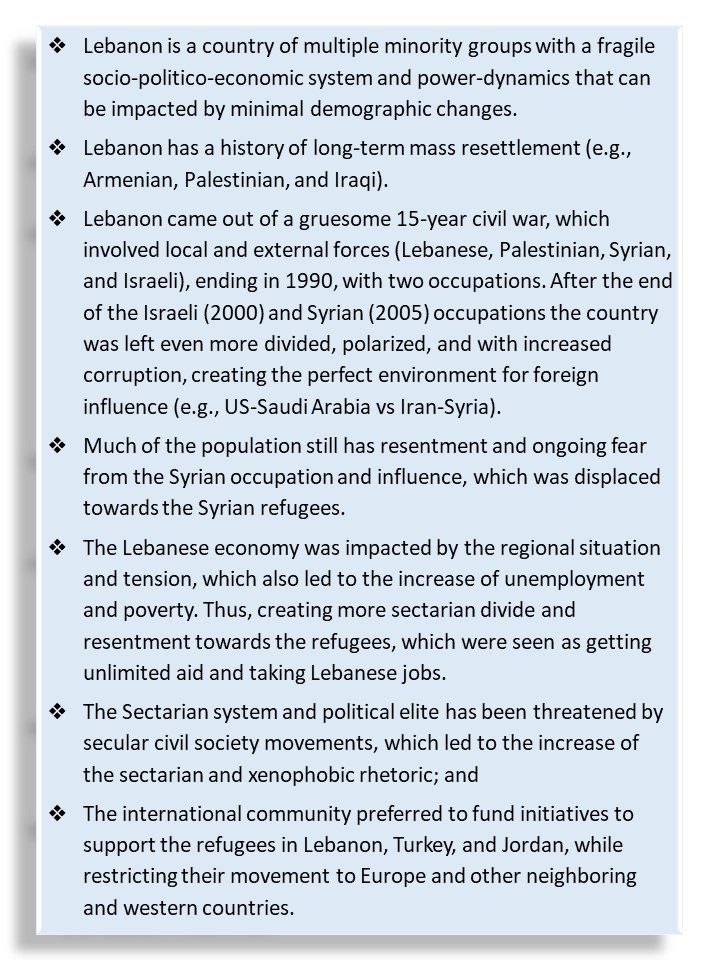

Lebanon, for example, experienced an influx of Syrian refugees (a quarter of the population) due to the ongoing 2011 Syria conflict. As a result, the country also experienced an influx of International Non-Governmental Organizations (INGO) and Humanitarian Aid funding to support the refugee population. The situation eventually increased tension between host communities and refugees, and between different Lebanese sectarian groups, which can be attributed to the following factors shown below:

Factors Increasing Tensions

Taking this overview and factors together, this case study will focus on a 2014 project that I (author Ramy Barhouche) worked on, to empower Syrian and Lebanese youth, reduce prejudice and discrimination, and create a culture of dialogue, collaboration, and conflict transformation.

Community Assets/Needs

In the business development process of the project proposal, no formal community assets/needs assessments were conducted. Instead, a brief literature review of past reports, projects, and context were conducted to better understand the situation and needs. In addition, the proposal was developed in consultancy/collaboration with local partners.

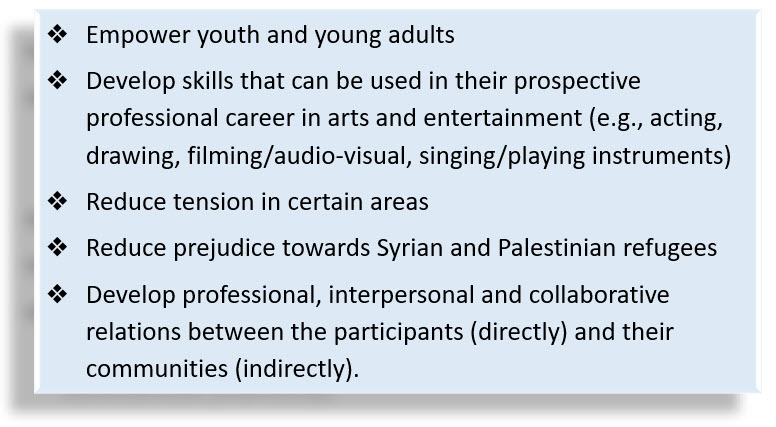

We found that youth and young adults in Lebanon have been facing a high level of unemployment. Thus we determined there was a need for capacity development to support prospective job seeking. In addition, we identified a growing market for the arts/entertainment field with little to no opportunities to further develop certain skills. Importantly, there was a rise of tension, prejudice, and discrimination, as mentioned above. As a result, the project team, through local partners, reached out to youth and young adults between the age of 15 to 25, from multiple socio-economic backgrounds (e.g., nationality: Lebanese, Syrian, Palestinian; Religion: Muslim, Christian, Druze; and economic class). With these factors in mind, the project was then designed to: (1) empower youth and adults, (2) develop skills that can be used in future careers, (3) reduce tension in certain areas, (4) reduce prejudice towards Syrian and Palestinian refugees, and (5) develop professional, interpersonal and collaborative relations between participants and their communities.

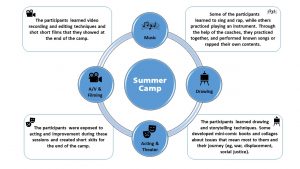

Some of the participants had previous experience with the designated arts (i.e. acting, drawing, filming/audio-visual, singing/playing instruments), while others had interest but never had the opportunity to be exposed to them. The project hired Lebanese, Syrian, and Palestinian coaches/artists to mentor the participants. The project also asked some of the more experienced participants (active volunteers in local organizations and those with experience in the arts) to act as peer mentors.

Collaborative Partners

The project team included a project coordinator, a project associate, and a monitoring and evaluation coordinator from the lead partner, as well as, the coaches and the implementing partners’ teams. We worked with two main local partners that were well established in the South and the Bekaa areas. Their relationship with the communities allowed us to better understand the local context and gaps/needs, reach out to Syrian and Lebanese youth and their parents, and recruit interested participants. The partners were part of the strategy team and were also responsible for the local implementation, support, and follow-up with community members, and logistics. The coaches and the coaches-artists came from Lebanese, Syrian, and Palestinian backgrounds and were responsible for teaching and mentoring participants in the four arts/entertainment skills: acting, drawing, filming/audio-visual, singing/playing instruments.

Description of the Project

With the foundation in place, the project was set to begin. The following discussion describes the components of the project:

The Summer Camp

Participants were invited to a one-week summer camp in each of the two areas. On the first day, the participants went through orientation and were matched with youth from different communities, and then were assigned separate tents. The sessions began the next day, and 100% of the participants went to all art sessions to explore and decide which to focus on. The sessions had a theoretical and practical aspect. Figure 1 below shows the model used for the summer camp.

Figure 1: Summer Camp Model

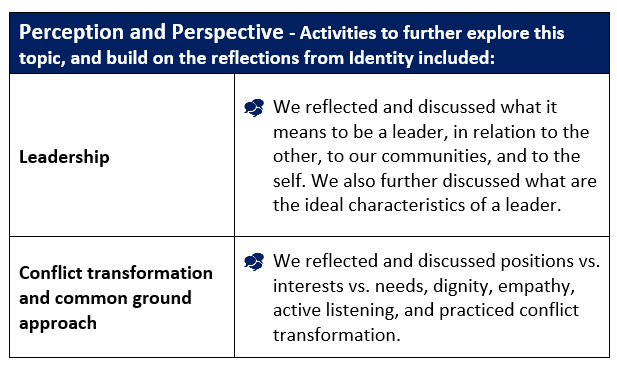

The participants also went through several sessions that focused on social capital and conflict transformation. They were exposed to activities related to the topics, and then had a chance to discuss and reflect on these issues, while linking them to their life experiences, which included narratives on Identity and Perception and Perspective shown below:

The project team also provided individual psycho-social support with a relational needs approach[1]. The participants shared things related to their struggles as refugees, family, relationships, life, as well as to issues that arose because of the camp. We also made sure to address every conflict that arose during the camp and had sessions with the individuals and/or groups that were involved in them. At the end of the day, the team also conducted debrief sessions for the participants and the project team (organizers + coaches) to reflect and assess the day and discuss possible changes.

After the Camp

A similar model was implemented the remainder of the year, where participants met regularly and continued their sessions while collaborating together to develop their art and content. After the year ended, they presented their work to their communities.

The following year, new participants were recruited, while some of the previous ones were asked to be peer mentors for the incoming ones. Meanwhile, the project included a monitoring and evaluation aspect that recorded all the progress of the participants, activities, and impact.

Outcomes and Impacts

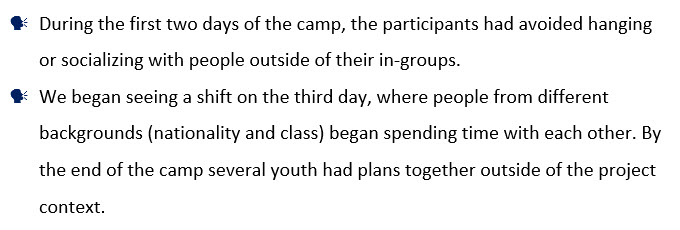

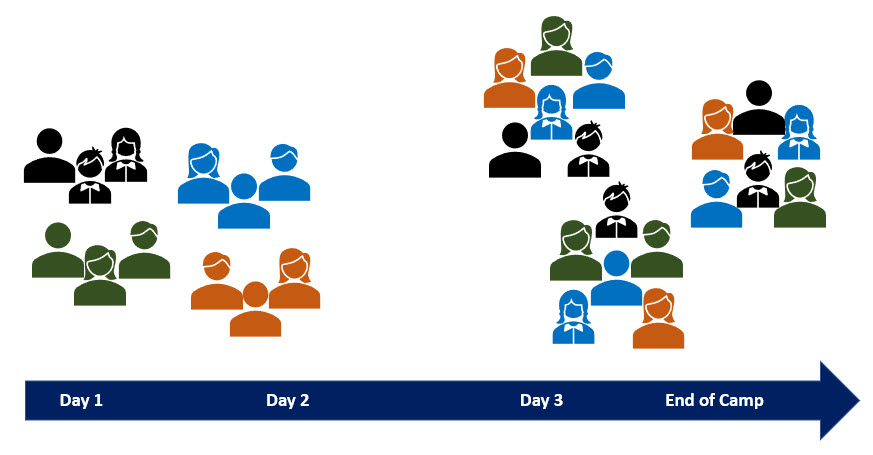

We began seeing signs of possible reduced prejudice by the end of camp. This assumption was determined from the following observation:

The participants continued building their relationships throughout the year, where they continued meeting regularly for the sessions and collaborating. They also continued meeting outside of the project context, even after it ended. The information about ongoing relationships is based on their social media accounts, as many followed the project team and stayed in touch. This is significant to us because many youths initially reported not having any friends or romantic relationships outside of their socio-economic background. Some of the participants today still collaborate on art and entertainment projects, while others took an NGO and civil society path. The participants have been actively involved with issues related to social justice, human rights, and anti-racism and gender equality campaigns.

Little impact was noticed within local communities or nationally. During the events held at the end of the project, some of the participants’ family members stated that their views changed due to their children’s relationships with others. However, no long-term or in-depth follow-up has been made for clearer results. In fact, in the following years, sectarian and xenophobic rhetoric increased, likely due to multiple reasons. At the time of this case story, we do not have the data at hand that sheds light on the reasons. However, as shared in the Lessons Learned and Recommendations section, moving forward, a summative evaluation on long-term changes should, if possible, be included in the program design.

Lessons Learned and Recommendations

The programmatic components of the project had some observed successes with the youth. The process allowed the participants to feel heard and be open to the experiences of others. Meanwhile, they were guided through the process and given tools to explore their realities and emotional well-being. Through the reflection sessions, the youth discussed topics related to their personal, relational, and systematic struggles and possible ways to overcome them and collaborate. This process was extremely important to provide the youth with some tools to further explore their perspectives, build relations with the other, and seek alternative options.

they were guided through the process and given tools to explore their realities and emotional well-being. Through the reflection sessions, the youth discussed topics related to their personal, relational, and systematic struggles and possible ways to overcome them and collaborate. This process was extremely important to provide the youth with some tools to further explore their perspectives, build relations with the other, and seek alternative options.

Importantly, it must be noted the project did not apply a multi-dimensional lens, especially when it came to policy and systematic change, and power dynamics. Rather, the project mainly focused on discrimination prevention and reduction, and cohesive living through interpersonal relationship building (e.g., conflict transformation) skills. This approach comes with the assumption that if the right tools are given to individuals and community members, they do learn to transform conflict and collaborate to achieve common interests. That perspective might work if ideal conditions are in place, however, unfortunately, there are too many factors at play that hinder such ideals. That was seen on several occasions in Lebanon.

The NGO I (Ramy) worked with had several projects running simultaneously, some worked with the community as a whole and municipalities, while others focused on youth, women, police, and/or refugees. We began seeing more leniency and openness towards Syrian refugees and collaboration with some of the communities we were working with. However, the sectarian and xenophobic rhetoric rose again due to the socio-politico-economic situation in the country and the region. This was especially seen with the rise of unemployment, decreased sense of security, and during political and economic crises. Further, with the recent rise of secular/social justice movements and revolution threatening the sectarian political elite and system, the bigoted and fear-based rhetoric has become more of a norm. Thus, working in the field came with limitations due to realities outside of the project team’s control. However, programming and organizational structure and process could be accommodated to better meet the needs of the communities, despite these circumstances.

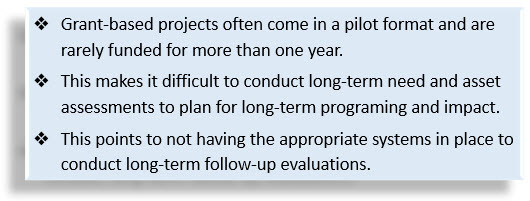

Creating alternative and preventative settings needs long-term planning and multi-level and multi-dimensional collaborations. However, this is extremely challenging to do with the structure of industrial non-profits/NGOs and the current socio-politico-economic systems in place. Challenges include: (1) limited grants for projects, (2) difficulty in conducting long-term need and asset assessments, and (3) not having the appropriate systems in place.

Additionally, it leaves NGOs in a constant cycle of seeking and applying for funding, which takes up much of their focus. At the same time, this forces the organizations in adapting and adjusting their program objectives and proposals to attract grantmakers and increase their likelihood of receiving grants. In addition, the bureaucratic structure of NGOs often forces program teams to focus on administrational tasks and reporting, leaving less time to focus on the programs and communities’ needs.

The overall budget and two-year duration of the ‘Better Together’ project helped some with implementation and allowed for more support. The project team included a project coordinator, a project associate, and a monitoring and evaluation coordinator from the lead partner, as well as, the coaches and the implementing partners’ teams. However, their capacity was spread thin, due to most people working on several other projects at the same time. Furthermore, there were challenges with the partnership’s distribution of tasks and communication, which created several obstacles along the way. Thus, more relationship building, clearer tasks, and conflict resolution processes are needed to be further developed and agreed on prior to the project.

Moreover, grants often come with predetermined objectives, agendas, and/or restrictions that better meet the interests of the international donors (e.g., governmental agencies, INGOs, foundations). The donor determines where and whom to work with or exclude and the structure and limitations of the program. Consequently, this restricts freedom for truly meeting the communities’ needs, sincerely taking into consideration local knowledge and lived experience, and is a form of imposing soft-power (neo-colonialism) on the country; which creates a vicious cycle. For example, for much of the duration of the war, European and U.S. donors rarely diplomatically attempted or funded peace initiatives in Syria, due to their opposition to the Assad Syrian regime and the complexity of the conflict. Rather, they focused their funding relief programs in host countries, such as Lebanon, Turkey, and Jordan. This funding later included more social cohesion and international development programs, as the war continued for years.

Looking deeper into the context, the situation in Syria and the region was caused by multiple factors, from foreign interference (geopolitics) to internal injustice, and water drought (climate change). Similarly, regional instability can be traced to the involvement of the U.S. and allies in the middle east long before the current Syria conflict. Their actions facilitated the creation of many extremist groups such as ISIS, which prolonged the Syria conflict. The same regime that the U.S. and allies oppose today, was endorsed to occupy Lebanon in the early 1990s because the regime supported their efforts against Saddam Hussein during the first gulf war. The Syrian Regime, in turn, used intelligence, brutal force, and collaboration with/overseeing Lebanese public agencies/government to control and oppress the people. This dynamic also created more division (Sunni vs Shia)[3] and more corruption in the country. Thus, much of the Lebanese were traumatized by a 15-year sectarian civil war, two occupations, and a corrupt system that did not allow the country to sustainably grow. In turn that trauma and anger were displaced toward the other and those most vulnerable, other sectarian groups and Syrian refugees.

Thus, the donors and countries that are trying to support and fund international development, are the same ones that had a hand in creating the current conditions that led to conflict and division in the region. When we discuss issues surrounding social justice and community psychology we should include geopolitics, coloniality, and global power dynamics. Coloniality in the Middle East takes multiple forms. Sometimes it looks Euro-U.S., while other times it takes the face of regional powers (i.e., Iran, Russia/USSR, Egypt, Israel, Saudi Arabia).

Other times it takes an ideological form (e.g., religion, pan-Arabism, communism, capitalism). This cycle often creates more local divisions and injustices. The reason this narrative regarding historical context is included is that to better support and collaborate with communities, we need to understand their context, history, struggles, and needs. While on the project in this case study, we barely had the chance to do so; and that seems to be indicative of most NGOs.

Although the funding is needed to support those lacking resources and the means to support each other, the funding often acts as a band-aid rather than a transformative solution. Other recommendations include thinking through how to design and implement preventative programming, along with the creation of alternative-based NGO structures that include multidimensional community and participatory-based programming. This programming should include process and relational-based aspects, as well as policy and systemic advocacy and change, in addition to communication and outreach aspects. This would include, human rights and social justice, education, investing in local economies, and long-term local and regional stability initiatives. It is also important to monitor and evaluate these efforts before, during, and after their implementation for learning opportunities.

Although the funding is needed to support those lacking resources and the means to support each other, the funding often acts as a band-aid rather than a transformative solution. Other recommendations include thinking through how to design and implement preventative programming, along with the creation of alternative-based NGO structures that include multidimensional community and participatory-based programming. This programming should include process and relational-based aspects, as well as policy and systemic advocacy and change, in addition to communication and outreach aspects. This would include, human rights and social justice, education, investing in local economies, and long-term local and regional stability initiatives. It is also important to monitor and evaluate these efforts before, during, and after their implementation for learning opportunities.

Looking Forward

I (Ramy) decided to move away from the NGO and nonprofit field for the time being. I am continuing my higher education earning my Ph.D. in Community Psychology. My applied research interests focus on social movements, power dynamics, social transformation, and decoloniality. I will be working in communities in Lebanon and North America, with a multi-disciplinary, decolonial, intersectionality, non-binary, and non-hierarchal approach.

Conclusion

Community psychology practice is integrated into four levels in this case study. The objective of the project was to create alternative and preventive settings that would reduce discrimination and prejudice, and develop collaborative living and conflict transformation. The project used a process-based relational approach, which was important to begin the conversation and develop the relationships for collaboration. Lastly, the program exposed participants to new perspectives, many of whom sought roles and activism opportunities related to social justice, gender equality, LGBTQ+ rights, as well as entertainment and arts.

However, it was important that the project did not include a policy, systemic, and advocacy-based approach. If included, this could have created tension with the local and/or national government, according to the NGO’s perspective. In addition, the project raised the team’s awareness of local contexts, but not international power dynamics or the structure of the nonprofit field. Therefore, this case study highlights the impact and the need for critical applied research of the impact and structure of NGOs, funders, geopolitics, and systemic change.

From Theory to Practice Reflections and Questions

- The case study shared that the summer camp participants engaged in training sessions covering the topics of social capital and conflict transformation (Barhouche, 2021). What does social capital mean for you and how would you cultivate it?

- Why does funding that NGOs or nonprofit organizations in the U.S., receive sometimes create a “band-aid” approach versus accomplishing true individual, family or community healing and change?

- Consider what, if anything, you would have done differently when trying to support the reduction of conflict, tension, and highly prejudice bigotry in the context of the Lebanese refugee community? If you would have done something different, what resources would be needed to make that happen?

Endnotes

[1] An approach that is based on the premise that everyone has relational needs (acceptance, approval, affection, appreciation, attention, respect, security, comfort, support, encouragement). Those needs can only be met by having an interdependent community, and with the golden rule of “treating others as they like to be treated”. Link: https://www.relationalcare.org/

[2] Pettigrew, T. F. (1998). Intergroup contact theory. Annual Review of Psychology, 49, 65–85. https://doi.org/0066-4308/98

[3] Lebanon has a confessional democratic system that represents the sects/religious groups in the country. The situation has often created fluctuating power dynamics and alliances that have been used by geopolitical powers for their benefit. Traditionally the Sunni Muslims have been the main power in the Middle East for centuries, with Shia, Christians, Alawites, Jews, and other minority groups being treated as second class. The situation changed with the creation of Lebanon, moving the leadership to the Christian Maronites, which created tension between them and the Sunni and Druze, which traditionally ruled the Lebanon region, and eventually led to the 1975 civil war. The Ta’if Agreement ended the civil war, by redistributing power which allowed the rise to the Sunni and Shia leadership, and weakening the Maronite leadership and role in the government. The Sunni leadership was supported by Saudi Arabia (Sunni) and the US, while the Shia leadership was supported by Syria’s Assad regime (Alawite Muslim) and Iran (Shia). Thus, this situation created more rivalry and division.

Feedback/Errata