12 S.U.P.P.O.R.T. for Unhoused Individuals with Substance Use in Service Planning Area 6 in Los Angeles, California

Briana Lopez, Stephania Luna, Madilynn Reynoso, Ngozi Alia, Jalen Castille, Austin Hudson, Fatimatou Saka, Nyoko Brown, Alexander Afewerki, David Heredia

Big Picture/ Background of How We Came to Work with This Community

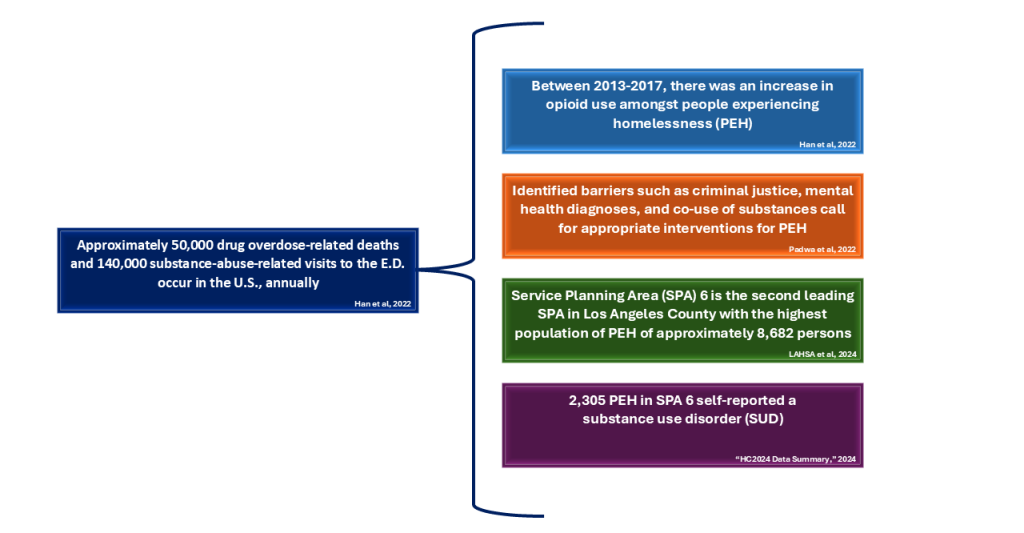

The United States has experienced 50,000 drug overdose-related deaths and approximately 140,000 substance-abuse related visits to the emergency department, annually (Han et al., 2022). People experiencing homelessness, or PEH, are at an increased risk of this alarming statistic because of the structural barriers that would otherwise reduce overdose-related deaths and co-morbidities (Han et al., 2022). Structural barriers including unstable housing, criminal justice involvement, and access to medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) (Han et al., 2022), have led to discourse amongst experts on how the U.S. should implement national efforts to ease the burden for PEH with lived experiences of substance use disorders (SUDs).

A 2022 study by Han et al., found that between 2013 and 2017 SUDs among PEH had increased, and that first-time SUD treatment admissions in the United States were predominantly among males who injected substances such as methamphetamine and cocaine. PEH were also less likely to receive outpatient treatment or receive MOUD (Han et al., 2022). In addition, Han et al. showed that there was a statistically significant increase in co-occurring psychological issues, or mental health, and methamphetamine use in PEH (Han et al., 2022). Although the study acknowledges that there was increased use of residential detox facilities and long-term facilities amongst PEH in 2017, there remains an issue of PEH receiving MOUD in comparison to non-PEH (Han et al., 2022). This disproportionate use of long-term facilities for treatment is believed to occur because of the need for housing (Han et al., 2022).

This national trend has been reflected similarly in publicly funded SUD treatment for PEH in California. Padwa et al.’s 2022 observational study highlighted the importance of appropriate treatment for SUDs. By analyzing the California Outcomes Measurement System, a database of reported publicly funded SUD treatment services delivered in California from 2016 to 2019, Padwa et al. (2022) found that there was co-use of substances, such as methamphetamine and heroin, and identified barriers such as criminal justice and mental health diagnoses, underscoring the need for appropriate interventions while treating the SUDs itself. In addition, PEH were likely to receive residential treatment but experienced a lack of outpatient treatment. Although effective treatments for SUDs exist (however, not widely available) there remains the issue of housing insecurity, as Padwa et al. highlighted.

Models such as the “Housing First,” which originated by Dr. Sam Tsemberis, the founder of Pathways to Housing, who pioneered the model in the early 1990s, can allow for PEH to receive housing without any prior requirement of rehab or treatment for mental health disorders to help minimize barriers to housing (Davidson et al., 2014). The model focuses on a “client-centered approach” that empowers open communication and does not require participation in supplemental rehab treatment to yield autonomy to the individual, a requirement in the traditional shelter-based model. (Davidson et al., 2014). There is concern that the open housing approach could harm other individuals in the same housing and on their journey for SUD recovery and that stable housing wouldn’t treat the substance use disorder; however, this model is also cost-saving for the government and believed to at least stabilize or improve SUD (Davidson et al., 2014). This nationwide issue of housing instability and substance use disorder among PEH is also experienced in Service Planning Area (SPA) 6 of Los Angeles, California where us we medical students are conducting our medical training at Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science

Service Planning Areas (SPAs) are divisions within Los Angeles County that aids the Department of Public Health in determining what public health services and clinical services would benefit the specific needs of residents in each region (“Service Planning Areas,” n.d.). Los Angeles County is divided into 8 SPAs, with SPA 6 serving Athens, Compton, Crenshaw, Florence, Hyde Park, Lynwood, Paramount, and Watts, pictured in Figure 1 (“Service Planning Area 6,” n.d.).

According to the 2024 Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count Report, conducted by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (LAHSA), the annual point-in-time count of people experiencing homelessness in LA County was 75,312 (2024). Additionally, the LAHSA report estimated a total of 8,682 persons experiencing homelessness (PEH) in SPA 6, which ranks behind SPA 4, or the Metro Area, with 12,185 PEH (2024). Notably, the report also documented that 54% of the newly unhoused population attributed their housing status to economic hardship (LAHSA, 2024). The LAHSA report indicated that 27% of PEH self-reported a substance use disorder (2024). In a separate data summary published by LAHSA that further breaks down PEH characteristics, 2305 individuals self-reported a SUD in SPA 6 (“HC2024 Data Summary,” 2024). However, as stated in the LAHSA Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count Report, these numbers are “imprecise estimates” that are dependent on shelter bed counts, self-reported data, and only comprise a snapshot of one day in Los Angeles (2024). See Figure 2 summarized statistics.

The most recent report from the Department of Health Services of County Los Angeles, published in 2002, that monitored community health indicated that SPA 6 had the highest rate of drug-related death among adults (“Key Indicators of Health,” 2002). According to the Los Angeles County Substance Abuse Prevention and Control (SAPC) Program, of the patients who received treatment from publicly funded treatment programs in Los Angeles County, 11,464 were unhoused, which accounts for 33.9% of patients from 2021-2022 (“Annual Overview,” 2023). It has also been noted by the SAPC that these reflected percentages may be underestimated due to the COVID-19 impact (“Annual Overview,” 2023). Furthermore, among residents of SPA 6 who received SUD treatment, there were 3,497 patients, making up a total of 10% of the patients treated (“Annual Overview,” 2023). However, there was not a breakdown of how many of the SPA 6 residents were unhoused at time of treatment. In addition, this doesn’t include PEH that have not been able to seek treatment.

Overall, these findings emphasize the need for research and support measures that focus on the underserved community of SPA 6 so that this area can see the true impact of SUDs among PEH and better adjust resources to helping these vulnerable members of our community. As mentioned above, since SPA 6 is the home to our medical school, Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science, SPA 6 and its community are the driving force for us medical students at the College of Medicine to address health inequities and leverage changes to support PEH and those affected by a SUDs.

Description of the Framework Developed

The aim of this research project is to provide a framework that gives a comprehensive analysis of Los Angeles County’s SPA 6 demographic data, health data, and social conditions to underscore the urgent need for targeted intervention strategies that can help physicians implement a comprehensive strategy that addresses the unique challenges faced by PEH struggling with SUDs in SPA 6.

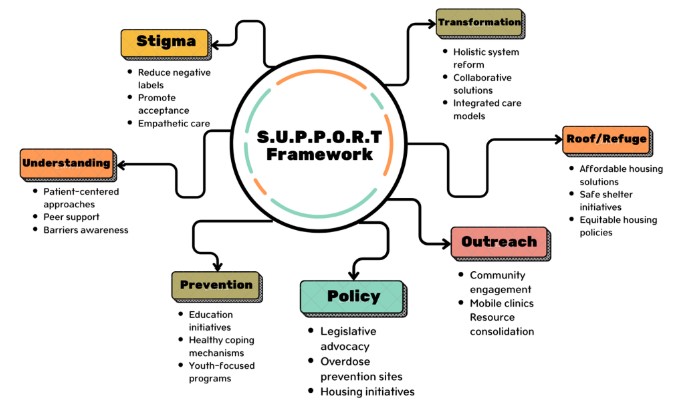

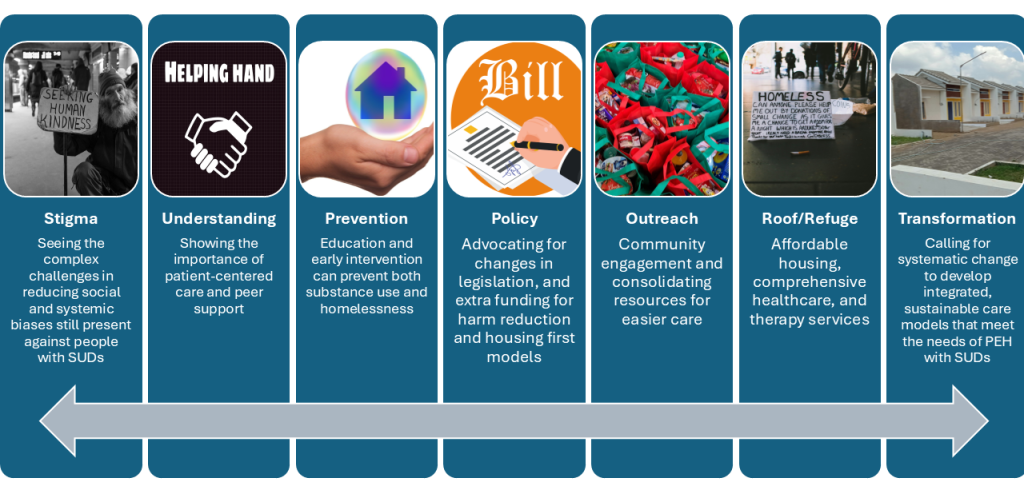

The “S.U.P.P.O.R.T. for Unhoused Individuals with Substance Use in SPA 6” framework (Figure 3) provides the following pillars to understand the complex links between homelessness and SUDs in our community of SPA 6.

Due to the widespread health and social inequities present in SPA 6, the S.U.P.P.O.R.T. framework above was created after seeing it as a necessity to link the relevant literature on what has been successful for tackling SUDs in other regions among PEH, what SPA 6’s community advocates find is needed, and what can work for our specific community members here in SPA 6. This framework was intended to understand and inform physicians working within our community of SPA 6 on how the complexities of social determinants of health can lead their patients into experiencing homelessness and dealing with SUDs.

Given that the S.U.P.P.O.R.T. framework was a novel concept developed by our team of medical students, it makes up the backbone of how we approached our research project. It spearheaded the discussions we had with community advocates so that we could find commonality between the factors that contribute to, and the factors that can mitigate, substance use among PEH. By using the S.U.P.P.O.R.T. framework to organize our findings, we wanted to create a clear link between why we chose this population for our community engagement research project and the insights we collected. Talking with a wide range of people, such as healthcare workers, those who have lived experience with SUDs and homelessness, and people from law enforcement, and community-based organizations, created a deeper understanding of key themes impacting PEH with SUDs in SPA 6. Through our research, we discovered just how strongly stigma affects communities, how vital culturally sensitive outreach is, and why integrated policy efforts really matter. This feedback helped us fine-tune our framework, spotlighting the main obstacles that could guide physicians on future strategies or policy work.

Importantly, we do not see the S.U.P.P.O.R.T. framework as something ready to bring to the community just yet, but more as a resource that gives physicians insight into how social determinants of health (SDOH) impact their patients with hopes that it will spearhead future community efforts. We see S.U.P.P.O.R.T. as a concept-driven tool shaped by previous research and the valuable stories we heard through our interviews with community advocates. This gives a solid starting point for future studies to dig deeper, test, and improve on the framework. Our ultimate aim is to craft specific, evidence-based solutions that can help PEH with SUDs overcome the challenges they face.

Figure 4. Pillars to understand links between homelessness and SUDs in SPA 6 community.

Community Needs

When given the opportunity to converse with experts on the matter such as a family medicine physician and addiction medicine specialist working in SPA 6, one can appreciate the role health disparities play in addiction medicine. The dialogue with this physician analyzes the strategies and challenges involved in providing care for individuals with SUDs. Their insights shed light on the practical needs of their patients and underscored the importance of patient navigators in connecting unhoused patients with essential resources, highlighting the lack of consolidation of services in SPA 6. For the reasons listed above, they advocate for harm reduction initiatives and emphasize the need for tailored support and addressing housing instability. Moreover, they stress the significance of relatability and nonjudgmental support in effective care from physicians. This dialogue highlights the importance of empathy, language, and community collaboration in treating SUDs and improving healthcare access for affected individuals.

Additionally, patients may not feel comfortable seeking care due to stigmatizing language and/or not being acknowledged at care sites. Finally, services are often interrupted due to funding for these programs or a patient’s own inadequate access to health insurance. In addition to barriers to receiving treatment, care may not be individualized enough to the patient’s needs. The family medicine physician we spoke to highlighted how women specifically face persistent gender-specific challenges and societal expectations to be stronger than their challenges, further complicating their ability to receive treatment. Still, a hopeful sentiment came from our interview, which was that effective treatment is available, but to address these disparities, there has to be an expansion of harm reduction efforts, an increase in the number of patient navigators, and a shift in the narrative surrounding SUDs. These efforts provide a step towards equitable care for patients with SUDs.

To further highlight the community needs and to gain insight from someone with lived experience in SPA 6, we interviewed someone from SPA 6 who has experienced using substances while experiencing homelessness. They discussed the difficulty of accessing resources without legal system involvement. This reliance on the judicial system highlights gaps in outreach and accessibility. Research supports patient-centered approaches for better engagement and outcomes (SAMHSA, 2019). They also emphasized the importance of peer support in recovery, stating, “They need support, monitoring, and people around…it’s also about accountability.” Research confirms that peer-led interventions improve recovery by fostering relatable success stories and empathetic support (Tracy & Wallace, 2016). Such models empower individuals and reduce stigma, creating a more inclusive recovery environment.

To further highlight the community needs and to gain insight from someone with lived experience in SPA 6, we interviewed someone from SPA 6 who has experienced using substances while experiencing homelessness. They discussed the difficulty of accessing resources without legal system involvement. This reliance on the judicial system highlights gaps in outreach and accessibility. Research supports patient-centered approaches for better engagement and outcomes (SAMHSA, 2019). They also emphasized the importance of peer support in recovery, stating, “They need support, monitoring, and people around…it’s also about accountability.” Research confirms that peer-led interventions improve recovery by fostering relatable success stories and empathetic support (Tracy & Wallace, 2016). Such models empower individuals and reduce stigma, creating a more inclusive recovery environment.

The interview further revealed major shortcomings in county-run facilities. Anonymous criticized their effectiveness, stating, “The county options are…not sufficient. I would never send anybody to a county facility like that…it was so bad…what we have is…not working.” While some argue for incremental improvements, research suggests a need for systemic overhaul, especially for marginalized populations (Padgett et al., 2016). Based on these insights, key recommendations include expanding outreach programs to proactively connect with PEH, increasing affordable treatment options through policy changes, and implementing educational initiatives to inform communities about SUDs. Additionally, improving county-managed treatment facilities could provide more dignified and effective care, addressing the systemic failures identified in our research.

The interview further revealed major shortcomings in county-run facilities. Anonymous criticized their effectiveness, stating, “The county options are…not sufficient. I would never send anybody to a county facility like that…it was so bad…what we have is…not working.” While some argue for incremental improvements, research suggests a need for systemic overhaul, especially for marginalized populations (Padgett et al., 2016). Based on these insights, key recommendations include expanding outreach programs to proactively connect with PEH, increasing affordable treatment options through policy changes, and implementing educational initiatives to inform communities about SUDs. Additionally, improving county-managed treatment facilities could provide more dignified and effective care, addressing the systemic failures identified in our research.

Collaborative Partners

To effectively combat the substance use crisis among PEH in SPA 6’s, physicians must utilize a multi-pronged approach. First, physicians must advocate for public policy and speak to local governments for increased funding at city and county levels for programs addressing prevention, treatment, harm reduction, and recovery for SUDs. Additionally, physicians should try to lobby for the passage of the Modernizing Opioid Treatment (MOTA) Act at the federal level to significantly improve access to methadone treatment. Secondly, implementing Dr. Hurley’s, an addiction medicine physician, the Medical Director for Los Angeles County’s SAPC, and the President of the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM)’s, suggestion of bringing treatment directly to unhoused communities is crucial. This can involve mobile clinics stationed in high-need areas, alongside partnerships with shelters, and outreach programs to ensure easy access.

Finally, addressing the lack of perceived need identified by Dr. Hurley requires focused outreach and engagement with PEH. Physicians should try to provide clear information to their patients about substance use, highlight the benefits of treatment, and dispel misconceptions to encourage help-seeking behavior. By implementing these steps, we can create a more comprehensive and accessible system of care for SPA 6’s PEH struggling with SUDs. To appropriately address the issue of substance use in PEH in SPA 6, housing must be seen as a harm reduction approach, which can be addressed through housing initiatives, to minimize the negative consequences of substance use through non-judgmental, evidence-based strategies, prioritizing safety, health, and well-being over the immediate need to get sober.

Furthermore, in the pursuit of effective interventions for PEH struggling with SUDs in SPA 6, engaging community experts through targeted interviews is essential. These interviews serve as a platform to gather insights and perspectives from those directly involved in addressing these pressing issues. By formulating key questions, establishing clear goals and objectives, and fostering collaborative partnerships, we can create a comprehensive strategy that meets the unique needs of this vulnerable population.

To gain a deeper understanding of the challenges and needs within SPA 6, it is crucial to ask community experts a series of targeted questions. First, we must explore the primary challenges they face in addressing homelessness and SUDs. Questions such as:

- What are the primary challenges you encounter in your work?

- How do you perceive the current support systems for PEH?

These types of questions can elicit valuable insights into the systemic barriers that hinder effective intervention.

In order to address these barriers, they must first be understood. Additionally, understanding resource allocation is vital. Community partners should be asked about the resources they believe are most critical for supporting PEH and how funding can be better allocated to meet these needs. Furthermore, inquiries regarding the effectiveness of existing policies and programs can reveal which initiatives are working and which require reform. Questions like:

- What are the trends of PEH with SUDs, do we have less PEH with SUDs or are the numbers increasing?

- Which existing policies do you find effective, and which do you think need reform?

These types of questions can guide discussions toward actionable solutions.

Finally, exploring collaboration and communication is essential. Community partners should be prompted to share their thoughts on how different organizations, such as community clinics, criminal justice systems, and community-based organizations, can improve collaboration by identifying promising partnerships, seeing how communication strategies have proven effective in engaging the community and improving outcomes for our community members experiencing homelessness with SUDs. This dialogue can uncover opportunities for enhanced cooperation among various entities working toward a common goal. The overarching goal of these interviews is to gather insights that will inform the development of effective interventions for PEH with SUDs. To achieve this goal, several specific objectives must be established:

- First, it is important to identify the specific needs and challenges faced by community partners in addressing homelessness and substance use. Understanding these challenges will provide a foundation for developing targeted interventions.

- Second, the interviews aim to assess the effectiveness of current policies and programs from the perspective of those on the front lines. By gathering feedback on existing initiatives, we can identify areas for improvement and reform.

- Third, exploring opportunities for collaboration and resource sharing among community experts will enhance the collective impact of our efforts.

- Finally, gathering recommendations for policy reforms and program development will ensure that our strategies are informed by the experiences and insights of those directly involved in the field.

Building collaborative partnerships is a critical component of addressing the intertwined issues of homelessness and substance use. Engaging with community leaders and organizations that have established trust with PEH is a vital first step. These leaders can provide valuable insights and facilitate better outreach and support.

Fostering trust among community experts is equally important. Open dialogue, transparency, and respect are essential in building relationships that encourage collaboration. By engaging community partners in discussions about their experiences and needs, we can ensure they feel heard and valued, which can lead to stronger partnerships. Establishing shared goals and a common vision is another key aspect of collaboration. By working together to define shared objectives, community experts can enhance their commitment and cooperation.

Regular communication is also crucial; establishing consistent meetings and communication channels will keep all partners informed and engaged, allowing for updates on progress, challenges, and opportunities for collaboration. Encouraging resource sharing among community partners can lead to more effective interventions. By leveraging the strengths of different organizations, we can create a robust support network for PEH. Additionally, developing joint initiatives or programs can enhance impact and provide comprehensive support to individuals in need.

In conclusion, addressing homelessness and substance use disorders in SPA 6 requires a multifaceted approach that includes:

- Engaging community experts through targeted interviews,

- Establishing clear goals and objectives, and

- Fostering collaborative partnerships.

By focusing on these areas, we can gather valuable insights, enhance cooperation among organizations, and ultimately create a more effective support system for PEH struggling with SUDs (Alderwick, 2021).

Expert Perspectives

Dr. Ricky Bluthenthal, Associate Dean for Social Justice and Vice Chair for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion at USC’s Keck School of Medicine in Los Angeles, discussed with us the harmful effects that the public news, performative politics, and the scattered legal and social systems have on the health of PEH, and specifically those with substance use.

As we continue to read how the local news criminalizes and negatively portrays PEH in SPA 6, we witness how this can promote fear in the public and unjustly influence politics. As California has seen an increase in methamphetamine and heroin use amongst PEH and receiving publicly funded treatment for substance use disorders, this highlights the importance of investing in evidence-based treatments that would not only treat SUDs, but also consider co-use of substances (Pawda et al., 2022). In addition to co-use of substances, PEHs are more likely than those not experiencing homelessness to encounter co-occurring mental health diagnoses (Pawda et al., 2022). However, there continues to be much debate amongst literature about whether policy should focus funding and efforts on housing or substance use services first.

The Housing First approach, mentioned previously, aims to end homelessness by providing permanent housing to individuals without requirements such as sobriety or treatment participation. This is based on the philosophy that stable housing is a necessary foundation to successfully address other issues. It is supported as being the most effective means to improve housing retention and reduce the utilization of public resources. However, it is also argued that this model overlooks underlying problems, such as substance use, by not incorporating treatment as a requirement. Similarly, harm reduction strategies (i.e. needle exchange programs) aim to reduce the risk of overdose and blood-borne disease spread; this, too, has its criticism as it could simply enable drug use rather than directly addressing the root cause. Both philosophies reflect a larger tension between providing immediate safety and supporting long-term behavioral change and recovery.

Similarly, Dr. Bluthenthal introduced the Trieste Model, an individualized holistic substance use treatment infrastructure set in northern Italy’s city Trieste, described as “radical hospitality” (Heart Forward, 2024). The philosophy is to assist someone in returning to society and their lives by asking them what they need, whether they may need financial assistance first, housing or treatment, and includes readily available psychiatric help (Heart Forward, 2024). As this model cannot be implemented overnight, in effort to close the gap in care, Dr. Bluthenthal encourages continuous active screening for SUDs and mental health conditions, particularly in PEH, and proactively connecting them with resources such as housing assistance, mental health services, and substance use treatment programs. It is imperative for physicians to actively engage with the unhoused patients and communities, to work to dispel misconceptions about SUDs and raise awareness about available treatment options. He also recommends that all community experts work alongside street medicine teams, to listen to the stories of PEH with SUDs, emphasizing the value of firsthand experience when shaping effective interventions and policy.

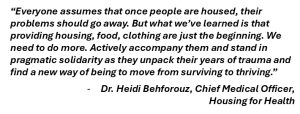

Dr. Heidi Behforouz – a physician, social justice warrior, and the current Medical Director of Housing for Health (HFH) at the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services (LACDHS) – discussed with us her current project: implementing contingency pilot programs for individuals using meth and establishing harm reduction health hubs in Skid Row. She is also a massive proponent of the Housing First model and advocates for developing programming that prioritizes safety first. On a governmental level, she appeals for the expansion of low-income housing and improvements in the SDOH that can severely impact people of color, struggling with housing insecurity and substance use.

Dr. Heidi Behforouz – a physician, social justice warrior, and the current Medical Director of Housing for Health (HFH) at the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services (LACDHS) – discussed with us her current project: implementing contingency pilot programs for individuals using meth and establishing harm reduction health hubs in Skid Row. She is also a massive proponent of the Housing First model and advocates for developing programming that prioritizes safety first. On a governmental level, she appeals for the expansion of low-income housing and improvements in the SDOH that can severely impact people of color, struggling with housing insecurity and substance use.

The systemic challenges surrounding substance use and homelessness require a holistic treatment approach that goes beyond addressing one issue alone. It is essential to recognize the interconnected issues of housing, economic stability, and mental health. Individuals experiencing housing insecurity often turn to substances as a coping mechanism for the hardships they face, creating an unfortunate cycle where substance use exacerbates housing instability and other social problems. Mental health disorders frequently coexist with homelessness and substance use, adding another layer of complexity and highlighting the need for comprehensive interventions that holistically treat and support patients.

Lessons Learned

- Collaboration is Crucial – partnerships with community organizations are essential to create a comprehensive system of care and develop programming that meets the unique needs of individuals and families.

- Patient-Centered Care Matters – actively listening to a patient’s story, respecting their perspective, and tailoring treatment plans to their individual needs.

- Addressing Barriers to Treatment – lack of perceived need, rather than lack of awareness of services, can be a primary barrier to treatment for many PEH. To provide quality care as physicians, it is necessary to understand each patient’s situation and customize interventions accordingly.

- Advocacy is Key to Change –bridging the gap between the perception of substance use as a health issue and the policies governing its treatment and pushing for reform that addresses the systemic factors that contribute to SUDs in PEH, bridging the gap between the perception of substance use as a health issue and the policies governing its treatment.

- Engagement with Unhoused Communities is Essential – Dr. Hurley emphasizes the importance of healthcare professionals actively engaging with unhoused communities, dispelling misconceptions about SUDs, and raising awareness about available treatment options. Similarly, Dr. Bluthenthal’s recommendation to work alongside street medicine teams and listen to the stories of PEH illustrates the value of firsthand experience in shaping effective interventions.

- Multi-Faceted Approach is Necessary – These experiences provide invaluable insights into the specific needs of the community. These insights have profound implications for our role as physicians. The knowledge gained from Dr. Hurley’s interview and Dr. Bluthenthal’s recommendations underscores the importance of adopting a multi-faceted approach to patient care.

- Innovative Solutions Improve Access – connecting PEH with resources such as housing assistance, mental health services, and substance use treatment programs like Dr. Hurley’s Medications for Addiction Treatment (MAT) program, which utilizes phone consultations to expand access to care, demonstrate leveraging technology to expand access to care.

Looking Forward and Recommendations

The traditional models of addressing SUD in PEH have shown to be insufficient for addressing the unique needs of PEH, particularly in regions such as SPA 6, where unstable housing and limited access to rehabilitation services create significant barriers. Moving forward, the imperative is clear: resources and information must flow seamlessly within SPA 6 to empower providers to be able to adequately support and provide holistic care for patients with SUDs amidst housing insecurity. To address these challenges, a multifaceted approach is necessary, combining innovative care models, policy reform, and community engagement to focus on prevention and treatment. Therefore, we derived the following recommendations from the interviews with community experts and analysis of the literature.

Care Models

- Physicians should consider how SDOH are impacting patients and use this information to provide the necessary resources in their clinics that can provide information on housing, education opportunities, transportation services, etc.

- Look into implementing the Trieste Model or prioritize housing first, so patients’ foundational need for safety and security can be met. This includes removing sobriety as a prerequisite for programs that supply housing.

- Expand the use of mobile health clinics in SPA 6, to remove transportation and distance barriers for patients. This allows care to be delivered directly to PEH.

- Expand the use of social workers and patient navigators to assist patients with administrative burden during treatment and recovery.

- Integrate peer support programs into treatment plans to assist with patient accountability and support.

Policy Reform

- Increase funding at city and county levels for integrated programs that address prevention, treatment, and recovery for those with SUDs.

- Fund housing first initiatives and support legislation such as the MOTA Act to expand access to Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) (Davidson, 2014).

- Advocate for the use of harm reduction as a stepping-stone in treatment and recovery.

- Advocate for policies that contribute to changing the narrative around SUDs and PEH to reduce the negative effects of associated stigma that prevent people from asking for help.

Community Engagement

- Leverage technology, such as a phone application with available resources and an open forum for suggestions and questions, to strengthen collaboration and communication between community organizations, providers, and social services to ensure a seamless continuum of care from outreach to long-term support.

- Physicians should help to educate patients on the resources and programs available. Anyone who comes into contact with patients should know and have access to several resources available. Patients’ sources of information and programs available should not only be coming from law enforcement or the criminal justice system.

- Community organizations can place information pamphlets in healthcare facilities. Physicians can ensure patients are linked with social services or community organizations.

By integrating innovative and holistic care models, policy reforms, and community-based strategies, we can create long-term, effective solutions that significantly improve the health and well-being of PEH struggling with SUDs in SPA 6.

“Meeting people where they are at” is the distinct embodiment that the S.U.P.P.O.R.T framework proposes in providing services to PEH with SUDs in SPA 6, who more than likely do not have access to traditional healthcare settings. Understanding and acknowledging an individual or a community’s health capacity and vulnerabilities facilitates care on an individual’s or a community’s terms. This allows for collaborative relationships still rooted in patient autonomy and increases and promotes treatment and program adherence.

Furthermore, SDOH represents macroscopically how factors such as community safety, access to treatment, and housing significantly intertwine a community on an individual level. Consequently, addressing the broader and societal environmental factors like stigma, housing insecurity, and economic instability that negatively impact PEH with SUDs is essential. Part of the psychiatric treatment for our targeted population requires addressing one of the most prominent SDOH— housing. Consequently, continued advocacy for policy reform that improves access to SUD treatment and Housing –First and Trieste models serves as a backbone in providing and encouraging the utilization of health services. It also aligns with promoting accessibility and goes hand in hand with the expansion of mobile health services and peer support programs that further address the needs of PEH within SPA 6.

The emphasis on collaboration within the S.U.P.P.O.R.T framework from local physicians, community organizations, policymakers, and PEH with SUDs bridges the gap between creating and implementing interventions tailored to SPA 6. Collaboration entails working with all community experts and PEH with SUDs to develop goals and review interventions. Transparent conversations and data collection about the personal experiences of the PEH with SUDs are also necessary as they serve as the foundational block in achieving program and treatment adherence. Coordinated efforts and centralized locations between mobile clinics, shelters, and harm reduction programs are a physical embodiment of collaboration as they actively work to remove structural barriers to care. Lastly, insight and a particular focus on the knowledge of current and forthcoming legislation, health interventions, and the beliefs of PEH with SUDs allow for the design of a model that not only takes a holistic and synergistic approach but is also effective.

Overall, the S.U.P.P.O.R.T framework addresses accessibility and utilizes a comprehensive health approach to provide an innovative solution to a complex problem. The premise of the framework is based on collaboration and addressing the SDOH on an individual, communal, and governmental level. By identifying the intersection between SDOH and the multiple sectors, the S.U.P.P.O.R.T framework offers hope and a fair opportunity for all individuals to achieve optimal health.

References

Alderwick, H., Hutchings, A., Briggs, A., & Mays, N. (2021). The impacts of collaboration between local health care and non-health care organizations and factors shaping how they work: a systematic review of reviews. BMC public health, 21, 1-16.

Baggett, T. P., Hwang, S. W., O’Connell, J. J., Porneala, B. C., Stringfellow, E. J., Orav, E. J., & Singer, D. E. (2013). Mortality among homeless adults in Boston: shifts in causes of death over a 15-year period. JAMA Internal Medicine, 173(3), 189–195.

California Health Care Foundation. (2020). Substance Use in California: A Look at Addiction and Treatment. Retrieved from https://www.chcf.org/publication/2020-edition-substance-use-california/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). HIV and Injection Drug Use. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/hiv-transmission/injection-drug-use.html

Cheng, H., McGovern, M. P., Garneau, H. C., Hurley, B., Fisher, T., Copeland, M., & Almirall, D. (2022). Expanding access to medications for opioid use disorder in primary care clinics: an evaluation of common implementation strategies and outcomes. Implementation Science Communications, 3(1), 72. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-022-00306-1

Chiang, J.C., Bluthenthal, R.N., Wenger, L.D. et al. Health risk associated with residential relocation among people who inject drugs in Los Angeles and San Francisco, CA: a cross sectional study. BMC Public Health 22, 823 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13227-4

County Los Angeles Public Health Community. (n.d.). Service Planning Areas. LA County Department of Public Health and Field Services Division. http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/chs/SPAMain/ServicePlanningAreas.htm

County of Los Angeles Public Health Community and Field Services Division. (n.d.-b). Service Planning Area 6. LA County Department of Public Health. http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/chs/spa6/

County of Los Angeles Public Health. (2023, May). Annual Overview: Patients in Publicly Funded Substance Use Disorder Treatment Programs in Los Angeles County 2021-2022 Fiscal Year Health Outcomes and Data Analytics. LA County Department of Public Health. http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/sapc/MDU/SpecialReport/AnnualTxReportFY2122.pdf

Davidson, C., Neighbors, C., Hall, G., Hogue, A., Cho, R., Kutner, B., & Morgenstern, J. (2014). Association of Housing First implementation and key outcomes among homeless persons with problematic substance use. Psychiatric Services, 65(11), 1318-1324. 10.1176/appi.ps.201300195

Gelberg, L., Andersen, R. M., & Leake, B. D. (2007). The Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Services Research, 34(6), 1273–1302.

Han, B. H., Doran, K. M., & Krawczyk, N. (2022). National trends in substance use treatment admissions for opioid use disorder among adults experiencing homelessness. Journal of substance abuse treatment, 132, 108504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108504

Jones, K. F., & Mason, D. J. (2022). The False Dichotomy of Pain and Opioid Use Disorder. JAMA Health Forum, 3(4), e221406. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.1406

Los Angeles County Department of Health Services Public Health. (2002). Key Indicators of Health By Service Planning Area. lapublichealth.org. http://lapublichealth.org/wwwfiles/ph/hae/ha/keyhealth.pdf

Los Angeles County Department of Public Health. (2022). Opioid Response Strategic Plan. Retrieved from http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/sapc/MDU/MDBrief/OpioidResponsePlan.pdf

Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority. (2021). 2021 Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count Results. Retrieved from https://www.lahsa.org/documents?id=4555-2021-greater-los-angeles-homeless-count-results.pdf

Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority. (2024, June 27). SPA 6 HC2024 Data Summary. Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority. https://www.lahsa.org/documents?id=8158-spa-6-hc2024-data-summary

Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority. (2024, June 28). 2024 Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count Results (Long Version). Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority. https://www.lahsa.org/documents?id=8164-2024-greater-los-angeles-homeless-count-results-long-version-.pdf

Mackey, K., Veazie, S., Anderson, J., Bourne, D., & Peterson, K. (2020, December). Barriers and facilitators to the use of medications for opioid use disorder: A rapid review. Journal of general internal medicine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7728943/

Manhica, H., Straatmann, V. S., Lundin, A., Agardh, E., & Danielsson, A. K. (2021). Association between poverty exposure during childhood and adolescence, and drug use disorders and drug-related crimes later in life. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 116(7), 1747–1756. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15336

Miele, G. M., Caton, L., Freese, T. E., McGovern, M., Darfler, K., Antonini, V. P., Perez, M., & Rawson, R. (2020). Implementation of the hub and spoke model for opioid use disorders in California: Rationale, design, and anticipated impact. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 108, 20–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2019.07.013

Miler, J. A., Carver, H., Masterton, W., Parkes, T., Maden, M., Jones, L., & Sumnall, H. (2021). What treatment and services are effective for people who are homeless and use drugs? A systematic review of reviews. PLOS ONE, 16(7), e0254729. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0254729

Osilla, K. C., Dopp, A. R., Watkins, K. E., Ceballos, V., Hurley, B., Meredith, L. S., Leamon, I., Jacobsohn, V., & Komaromy, M. (2022). Collaboration Leading to Addiction Treatment and Recovery from Other Stresses (CLARO): process of adapting collaborative care for co-occurring opioid use and mental disorders. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 17(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-022-00302-9

Padgett, D. K., Henwood, B., & Tiderington, E. (2016). A qualitative study of structural barriers to the effectiveness of SUD care systems. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 91, 95-101.

Feedback/Errata