9 A Plan for Prevention: Measuring Equity from the Start

Tonya S. Roberson, Ph.D., MPH, DTR

This case study discusses using culturally tailored data collection tools when applying practical community-based participatory research methods to promote health equities for African American students at an HBCU.

The Big Picture

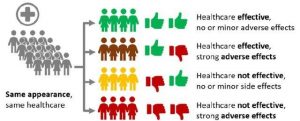

The United States has historically been a country struggling with racial and health disparities. Disparities in health outcomes and healthcare persist between racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups in the United States with African Americans (AA) suffering greater from chronic diseases such as cancer, heart disease, stroke, dementia, HIV/AIDS, diabetes, and the morbidity and mortality rates for African Americans far exceed that of White Americans (The State of Health Disparities). Working as a community psychologist and studying the impact of diseases and inconsistencies, I see patterns in health care inequities. African Americans get sicker and die at a younger age from preventable ailments and diseases than White Americans. Furthermore, the history of medical mistrust among African Americans has been justifiably consistent and long-lasting. In a 1966 speech on health care injustice to the Medical Committee for Human Rights, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., an African American Baptist minister and activist at the time shared, “Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health care is the most shocking and inhumane”. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., an African American Baptist minister and activist at the time shared a profound remark, “Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health care is the most shocking and inhumane”. These inequities result from a combination of individual and group behavior, lack of health and research knowledge, systemic inequality in economics, housing, and health care systems. African Americans have been underrepresented in medical research. Improving health disparities will require a methodical, purposeful, and sustainable effort to address issues including but not limited to health education and health literacy. The healthcare system cannot begin to address health issues or engage in prevention efforts if the patients do not understand what is being said to them. The patient needs to understand the information given to them to make informed decisions. Improved health education and health literacy will enable people to make informed decisions that lead to better health outcomes, family and social support, and access to health care which will ultimately help reduce disparities. The need to implement culturally specific research data collection tools to increase diversity and inclusion and increase the research participation of African Americans across ages to reduce the existing health inequities is imperative.

What Does Health Disparities Have to Do With It?

The United States (U.S.) government defines a health disparity as “a particular type of health difference that is closely linked with social or economic disadvantages. For example, did you know that in the U.S., Black adults are nearly twice as likely as White adults to develop type 2 diabetes? This racial health disparity has been rising over the last 30 years and continues to rise. Disparities exist in nearly every aspect of health, including quality of health care, access to care, utilization of health care, medication adherence, and health outcomes. These disparities are believed to be the result of the complex interaction among genetic variations, health literacy, environmental factors, existing zip codes, and specific health behaviors. Closing these multi-layered gaps in health outcomes is no easy task. Community Psychologists can better identify and address the needs of a diverse population when we consider health disparities. Solutions are more likely to endure if they address both the current cause of a given disparity as well as the circumstances that caused it to occur initially.

The most recent pandemic Covid-19 has heightened our awareness regarding health disparities in the United States. Drivers of health inequities have been debated through the years, but most notably include social determinants of health (SDOG) such as poverty, employment in low-wage, but essential worker jobs, and crowded housing situations (Riordan, Ford, & Matthews, 2020). In the public health arena, the importance of addressing all facets of SDOH to advance health equity has long been recognized and discussed. When developing solutions to health problems, community psychologists recognize the importance of culture and context rather than assuming a “one size fits all” will be effective. Often, adaptations are needed to fit individuals.

Think Globally, Act Locally: Lived Experiences

I have always considered myself a public servant and have been inspired by the words and work of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The following quote is from a 1965 speach in Selma, Alabama which speaks to the meaning of being a global citizen. “Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about the things that matter.” “Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about the things that matter.” I take this to statement mean that …those who recognize that a wrong is being committed and fail to make a change are not necessarily guilty of the wrongdoing, but neither are they acquitted of the harmful outcomes.

When my mother, a former educator, was diagnosed with breast cancer during a routine mammogram I witnessed firsthand what health disparities look like. During her bout with breast cancer, she and our family faced many racial and cultural barriers, provider stereotyping, and communication difficulties between my mother and her provider. This experience made me think seriously about the other patients that did not have the capacity our family had to advocate for her, yet face the same challenging experiences. What was their outcome going to be? Will they live or die if they decide not to go through with suggested procedures because of feeling uncertainty, intimidation, or like a ‘guinea pig’? Who was going to be the voice for them, and at that point, I said, “I WILL!” I began volunteering with community–based organizations and then working to conduct community-engaged research, recruiting research volunteers in underrepresented communities with large academic medical centers, healthcare organizations, and community-based settings. The more involved I became, the more I witnessed the medical mistrust that existed and the health and racial disparities. I started to focus on two important areas: health education and disease prevention strategies to promote improving the quality-of-care and quality-of-life of persons coping with a life-threatening illness.

Community Assets/Needs

“If we take the time to care about people, we can transform whole communities.

You never know how you can change someone’s life by showing him or her that you care.” – Rehema Ellis/NBC News

In my experience community-engaged research benefits from initially using a Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) approach. Community-Based Participatory Research involves an equitable partnership involving all research parties in all aspects of the research process from inception to dissemination. CBPR relies on “trust, transparency, dialogue, extending and building community capacity, and collaborative inquiry toward its goal of improving health and well-being” (Winkler & Wallerstein, 2003). I’ve found that “true” CBPR approaches in health disparities research take a least two years to develop and the process needs to be ongoing. CBPR combines the best of community and academic wisdom, experience, and knowledge to promote social change to improve community health and reduce disparities. The CBPR approach has been effective in impacting health outcomes such as asthma, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (Israel, Eng, Minkler, & Parker, 2012).

Within the last twenty years, CBPR has gained recognition within the public health sector and shown that community engagement is vital for effectively identifying and addressing health disparities. Many causes of health disparities and inequities include poor education, poor health behaviors of the group, poverty (inadequate financial resources), personal and environmental factors (USDHHS). Most of these factors are related to access. To impact health disparities and inequities we must strive toward holistic health equality for African Americans and other populations of color, the healthcare system must begin working to abolish the protracted consequences of racism. More meaningful data at the individual and cultural level should be collected among people of all ages, and then reviewed, and considered by both the members of the community and public health leaders and government decision-makers. This data and its review can be used to develop tailored health initiatives to improve health outcomes and increase equity. Including partnerships at the inception of the data collection process and culturally relevant data collection tools will increase the likelihood that the results are appropriately attained and accurately interpreted. The time has come for the political, economic, and social powers that have negatively impacted American medicine to reshape decisions that affect African American health policies. Assessments are conducted for various audiences, including researchers, funding agencies, private agencies, and policymakers and they must be culturally tailored for the target group. Researchers must then report factual and credible findings. Only then can health disparities be addressed and measured thoroughly and accurately.

Why Culturally Tailored Interventions?

Often evidence-based interventions are not tested with culturally diverse populations. Distinct cultural groups have unique needs and often fall through the cracks of service and healthcare systems. Interventions tailored for specific populations, can address these needs and reduce disparities. In order to improve African Americans’ health knowledge and willingness to participate in research, data collection instruments must be developed with the understanding that the respondents will only interpret questions and terms based on their own experience and context. Community psychologists working as researchers must aim to construct questions that are understandable and relevant to the group being studied to obtain the relevant information to combat the issue.

Dr. Robert Williams, an African American psychologist and professor who created the Black Intelligence Test of Cultural Homogeneity (BITCH-100) in 1972 because he saw the bias in intelligence tests towards White Americans. Dr. Williams also saw this as a problem because low test scores among African Americans were hurting their chances to secure jobs, gain entrance to certain schools, and access other opportunities supporting academic and economic success. Furthermore, receiving low intelligence tests scores was affecting African Americans’ self-esteem, confidence, and motivation to achieve and succeed. The test consisted of a multiple-choice questionnaire in which the examinee was asked to identify the meaning of 100 words as they were then used in what was labeled black ghettos. It took about two years for him to develop this culturally tailored test, and its purpose was to determine if his theory was correct. The results of the test showed that the Black group performed much better than their White counterparts. White students performed more poorly on this test than Black Americans, suggesting that there are important dissimilarities in the cultural backgrounds of Black and White participants. The results of these tests and examination of the BITCH-100 confirmed Robert Williams’ belief that his intelligence test dealt with content material that was familiar to Blacks.

Where Do I Start?

I put on my community psychologist’s hat and mulled over the fact that if Dr. Williams can prove that backgrounds are an essential part in the success of Black students and standardized testing, that background and culture are also vital in improving health outcomes and eradicating health disparities.

A Plan for Prevention

African American college students represent a unique population for promoting health. Although, African American research participation is restricted for relevant health disparities, especially among young African American adults. Limited data exist concerning the health of African Americans (AA). When health assessments are conducted at universities, AA students typically do not participate. Therefore, African American college students and further engaged research are necessary to collect accurate data. This additional data is vital in the development of health prevention and promotion interventions, activities, and services for this vulnerable student body. Armed with the data AA students can take on leadership roles and become advocates for health and peer-to-peer educators in eliminating racial/ethnic disparities and improving the quality of life of African Americans. Students at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) can serve as a model for promoting health equity and prevention, and HBCUs are in an ideal position to serve as excellent public health partners. Therefore, I developed a mixed-methods study, which was culturally tailored for Black college students at a private HBCU in Atlanta, Georgia. The study was designed to answer questions about health beliefs, health behaviors that tapped into the uniqueness related to the disparities in their health and wellness.

This study proposed to:

- Access the participants’ health perceptions, behaviors, and knowledge of Black college students at the HBCU,

- Identify and define critical problems and barriers of health, and

- Explore strategies to design sustainable health education and disease prevention interventions leading to better health.

Building Collective Impact

Building a productive and collaborative team of research partners is just the beginning. The team members’ ideas must be aligned, and promote sustainability. Many factors, such as identifying the right team members, building trust through good communication, and effective negotiation skills are needed to advance collaborative projects and to prevent and manage disputes and conflicts. I had to use my communication and interpersonal skills daily. I had to be open, forthcoming, and transparent while making a concerted effort not to over-deliver.

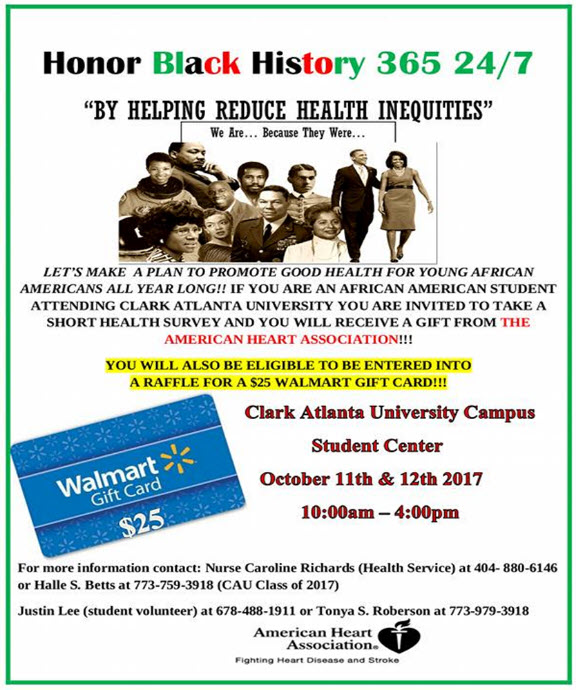

I conducted the study at Clark Atlanta University (CAU), an HBCU. Although I was from a different state, I was familiar with the operations, location, and culture of the school and campus because my daughter was a student. I strategically identified collaborative partners which included the Chicago local office of the American Heart Association, and a nearby Walmart Neighborhood Market to provide incentives for participants. Faculty members from Charles Drew University (another HBCU) and students helped with data collection. CAU-Research and Sponsored Programs provided leadership in the establishment of a partnership between a CAU research mentor, administering contracts, IRBs, faculty, staff and students, the institution, and its constituents. I further developed relationships at CAU with the PanHellenic Council (Greek Organizations), Student Affairs and Student Health and Wellness Center, and nurses. A unique approach was designed for this campus setting in Atlanta, Georgia to begin my work to identify and to increase student, faculty, and staff participation.

It became time to deliver. All hands were on deck! Initial recruitment relied on word of mouth until Student Affairs approved the recruitment flyer. Two to three weeks prior to the survey administration dates, the student health service director, the research mentor, eleven student volunteers, and I circulated recruitment flyers across the campus. Over 500 hundred flyers were posted in high traffic areas in program departments, classroom buildings, bus stops, dormitories, library, and student cafeteria. The Clark Atlanta University (CAU) administration also sent out a campus-wide email blast advertising and encouraging the students to participate. All college faculty members from various departments were contacted and asked to allow their classes to complete the 15-20 minute survey during class time. On the day of the survey collection, tables were set up, with volunteers and a variety of healthy snacks, in the Student Center; a heavy student traffic area. We offered incentives provided by the American Heart Association (ink pens, pedometers, towels, can strainers, and healthy cookbooks) given to each student that completed the survey. Upon completion of the survey, each student was also eligible to be entered into a raffle for $25 Walmart gift cards.

Description of the Project/Engagement

“Identify your problems but give your power and energy to solutions.” – Tony Robbins

My mom would always say, “There are a lot of problems but what are the solutions”? I believe that by conducting research in communities that emphasizes participation and action we can move toward developing effective solutions.

This project consisted of three main parts:

- The first part was an overall attempt to understand the structure and organization of student health and counseling services at universities and colleges across the country.

- Secondly, after reviewing this information, the task force identified university health centers defined as integrated and queried them more in-depth, focusing on the issue of integration.

- The third part consisted of follow-up case study interviews with selected center directors. Using the findings from the literature review, the task force developed a web survey including questions relevant to counseling, health perception, and knowledge.

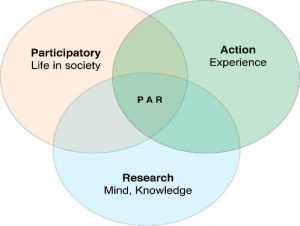

Participatory Action Research Approach

Participatory Action Research (PAR) is useful as stakeholders seek to understand communities and help facilitate their advancement because its approach views:

- research as conducted with people not on, or for people; and

- embraces processes that include “bottom-up organizing”.

To ensure an ethical stance is taken with this population, this study used a PAR approach. Unobservable community issues and problems can be identified through PAR. PAR usually involves any number of processes that include bottom-up organizing. PAR methods were used in every aspect of the development of this study including survey development, discussing the use of the data, and student interest in health promotion. Clark Atlanta University (CAU) students needed to be educated about the importance of participating in research, as there was limited data on the health of African American college students and further research was necessary to collect accurate and useful data. The goal was to use the data collected to develop sustainable, culturally-tailored programs to promote health equity on CAU’s campus.

Study Participants

Recruitment was remarkably successful. The participants (N=402) included CAU students 18 to 27 years old. Additional descriptive statistics are shown in Table 1 below.

| Classifications | Number of Participants |

|---|---|

| Freshman | 68 |

| Sophomore | 103 |

| Junior | 92 |

| Senior | 100 |

| Graduate/Professional | 18 |

| Not seeking a degree | 12 |

| Other | 9 |

Case Study Methodology

Research suggests that to address and attempt to eliminate health disparities, studies must incorporate a broad range of methodological approaches and cultural issues regarding the collection of data from racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic participants and other hard-to-reach populations (Stewart & Napoles-Springer, 2003; Sue & Dhindsa, 2006).

Examples of the methodological approaches of the project include:

- Mixed-method approaches to increase participation of otherwise hard-to-reach groups to provide context to quantitative data

- Community-based participatory action research (CPAR); and

- Collection of data across the life -course (Bulateo & Anderson, 2004; Halfon, Hochstein, 2002; Zarit & Pearlin, 2005).

Our survey also contained questions about the structure, rationale, and subsequent impact of integrating health and counseling services.

Survey Measures & Interview Protocol

The results from our study revealed the health perceptions, beliefs, and knowledge of this population. The analyses provided foundational information to strategize and design sustainable health education and disease prevention interventions for African Americans in the future.

The assessment contained demographic information as well as questions relevant to spirituality, family history, ethnic identity, HBCU culture, student’s health perception, behavior, and willingness to participate in future health promotions. The survey also contained questions about racism, health disparities, and clinical trials. The focus group protocol was comprised of open-ended questions for the students to answer and their answers were expected to support the assessment’s findings.

The complete culturally tailored survey questions were grouped into nine main domains:

- Health, health education, Family History, and Safety

- Alcohol, Tobacco, and Drugs

- Sex Behavior & Contraception

- Weight, Nutrition, and Exercise

- Mental Health

- Physical Health

- Oral Health

- Spirituality/Religiosity/Social Health

- Academic Performance

Focus Groups

Through this exploratory pilot, a focus group interview protocol and health assessment inquiries on the health needs of AA students were designed to establish whether the tools used were reliable and valid instruments for Clark Atlanta University to use in the future to help inform and develop health interventions. Interviews were open-ended and responses appeared to be candid and were detailed. The data analysis process consisted of five stages (1) familiarization of transcripts, (2) identifying thematic structures, (3) interpretation and selective coding, and (4) formulating categories. A common set of techniques for identifying themes, patterns, and relationships were vital to this study. Unlike quantitative methods, in qualitative data analysis, there are no commonly valid procedures that can be applied to generate findings. The analytical and critical thinking skills of the researcher are needed. No qualitative study can be repeated to generate the exact same results. The final stage of the analysis included linking the research findings to the research questions. Our analyses identified five focus group themes derived from the most common responses during the discussion. In this data analysis step, participants’ quotes were paired with the coded topic themes.

What Went Well

This project showcased positive collaboration building and teamwork. The communication was transparent and effective. This project set a pace for a truly equitable partnership. Buy-in from all parties: internal and external partners, faculty, staff, and students. Each party had ideas and a vision that aligned. The project involved collecting valuable information from and in partnership with a vulnerable population that could benefit from the results. The student volunteers as well as the student participants themselves were extremely interested, recommended great ideas, and were eager to learn and contribute. The Greek organizations served as leaders to help spread the word to a target population that we may not have otherwise been able to capture. Such positive school connectedness and valuable student leadership to disseminate health information in the future. Word-of-mouth about this much-needed project circulated among many other HBCUs increasing awareness and concern for the issue of health disparities. Since the completion of this study, I have been approached by Charles Drew University College of Medicine and Science conducting a similar study and project with their students.

Lessons Learned

The current manner used to assess college student’s health perception, beliefs and knowledge was developed and using The American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment (ACHA-NCHA) standards which do not provide a holistic, culturally tailored health report for people of color, especially African Americans. To reduce or eliminate health inequities and increase the overall quality of life, researchers must be able to identify which disparities need to be addressed and tailor data collection tools to do so. By regularly assessing, monitoring, and improving HBCU student’s health, African American students can leap forward to increase research and improve health and health outcomes not only for their campus but their communities. Evaluation of this data led to conversations about continuing this work and developing a combined student and staff steering committee to design and develop a sustainable, culturally tailored, holistic health education and disease prevention initiative to promote health inequity.

Implications for Policy

The data collected in this study can be an important resource for government leaders, policymakers, philanthropic foundations, and community non-profit organizations that are seeking to impact health, end racial health inequities and improve health outcomes.

This case study focused on a collaborative study that explored disparities in selected specific health determinants and identified promising programs and interventions that might be effective in reducing disparities. Focusing public and policymaking attention on fewer, more critical disparities that are potentially modifiable by universal and targeted interventions, can help reduce disparities (Robert Hahn, CDC, personal communication, 2010). However, until more evidence of effectiveness is available, I suggest the following actions:

- Increase community awareness of disparities as problems with solutions;

- Sett priorities among disparities to be addressed at the federal, state, tribal, and local levels;

- Articulate valid reasons to expend resources to reduce and ultimately eliminate priority disparities; and disadvantaged groups by allocating resources in proportion to need and a commitment to closing modifiable gaps in health, longevity, and quality of life among African Americans with the United States.

Relationship to Community Psychology Practice

This case study highlights the importance of more community-engaged initiatives for impacting health disparities and inequities among African Americans. Consistent with community psychology frameworks, community engagement activities are informed by local context and involve the community in problem identification and social justice action. Efforts to support and equip community members, leaders, and organizations to address the pressing and urgent needs of African American and minority families and communities are crucial.

Community psychologists can provide education and promote resilience with communities of color fostering proactivity regarding their personal and community health to reduce disparities and inequities. Partnerships are vital to the success of community psychology practice. When we seek to address problems through community interventions, we discover the importance of the environment and potential community partners (Shinn & Toohey, 2003). In other words, we need to understand the context of the neighborhoods and community settings where offer our thoughts on community interventions. Community psychologists can help develop culturally appropriate interventions that support and honor existing protective community practices, while helping to change those practices that may have a negative impact on health (Bronheim & Sockalingam, 2003). Thus, the community psychologist can act as a change-maker, health educator, and researcher to meet individuals and families where they are to promote health equity.

In general, health outcomes are inextricably linked with lifestyle choices, personal decisions, resources, and environmental factors and are influenced by culture, history, and values. Therefore, community-engaged interventions must focus on holistic development, community engagement in defining health promotion goals, and advocacy toward addressing the impact of racism and discrimination.

Marquita (name changed) a program participant shared, “The survey was… informative, descriptive and was very specific! It inspired me to want to have seminars about all the topics that were included, and I realized how much knowledge I didn’t have regarding the different types of health issues prevalent in the Black community. I feel that the survey will change the world!”

Conclusion

Community psychologists can use the advances in social sciences to provide education and support and build resiliency within communities regarding proactivity about their health to assist in reducing disparities and inequities. Health disparities ultimately impact everyone. It erodes human capital and the labor market suffers. As we have seen with the Covid-19 pandemic, the world is still trying to recover economically, culturally, politically, and environmentally. We can push forward a restored world when we work together. Partnerships are vital to the success of community psychology practice of co-creating spaces of health and wellness.

From Theory to Practice Reflections and Questions

- Improving health disparities will require methodical, purposeful, and sustainable efforts to address issues such as health education and health literacy for individuals and families to foster informed decision-making processes that can lead to better health outcomes…(Roberson, 2021). What immediately comes up for you or resonates with you when reading this statement?

- How would you use the narrative in this case story to promote health equity among African Americans or other populations?

- Discuss your understanding of the term “health inequities” and how would you co-create equitable health with those impacted?

References

Bronheim, S., & Sockalingam, S. (2003). A guide to choosing and adapting culturally and linguistically competent health promotion materials. Washington, D.C.: National Center for Cultural Competence, Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development https://nccc.georgetown.edu/documents/Materials_Guide.pdf

Bulateo, R.A., & Anderson, N.B. (2004) (Eds). Understanding racial and ethnic differences in health in late life. In National Research Council (US) Panel on Race, Ethnicity, and Health in Later Life: A Research Agenda. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2004. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK24692/ doi: 10.17226/11036 .

Halfon, N., & Hochstein, M. (2002). Life course health development: An integrated framework for developing health, policy, and research. PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12233246/

Israel, B.A., Eng, E., Schulz, A.J., Parker, E.A. (2012). Methods for community-based participatory research for health, 2nd edition. Jossey- Bass.

Riordan, B.C., Ford, R., & Matthews, F. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities. Epidemiology & Community Health. https://jech.bmj.com/content/jech/74/11/964.full.pdf

Shinn, M., & Toohey, S.M. (2003). Community contexts of human welfare. Annual Review of Psychology 54(1), 427-459. https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145052

Stewart, A.L, & Napoles-Springer, A.M. (2003). Advancing health disparities research: Can we afford to ignore measurement issues? PubMed, 4(11) 1207-1120. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14583684/

Sue, S., & Dhindsa, M.K. (2006). Ethnic and racial health disparities research: Issues and problems. PubMed, 33(4), 459-469. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16769755/

Zarit, S.H., & Pearlin, L.I., (2005). Special issue on health inequalities across the life course. The Journals of Gerontology, 60(2). https://academic.oup.com/psychsocgerontology/article/60/Special_Issue_2/S6/2965175

Feedback/Errata