Online Survey

The needs of the scholarly readers are rarely prioritized over those of other stakeholders in existing digital tools. While our in-person interviews allowed us to focus on some readers’ workflows, behaviours, and needs, we could not assume these to be representative of all researchers, or all readers, around the world. To better understand the varying needs of scholarly readers, we conducted a short online survey.

Methodology

Our online survey was modeled after our interviews, with similar questions regarding researchers’ approaches towards print and digital monographs, preferred citation and annotation tools, and workflows (please see Appendix iii for the full list of survey questions). We created a thirty-five-question survey using Survey Monkey. We distributed the survey in the Rebus Community and Rebus Foundation newsletters, as well in social media channels (Twitter and Facebook). The survey was open for roughly one month.

Summary of Results

We received a total of 104 responses to the online survey. Respondents were mostly from North America, despite our efforts to promote the survey to scholars in other parts of the world. To our surprise, the survey was answered not only by scholars (including undergraduate and graduate students, tenured and non-tenured faculty, independent researchers) but also by librarians, publishers, editors, instructional designers, experts in higher education policy, and university staff such as deans. This range of responses has reaffirmed the notion that a viable business model must consider the needs of a variety of stakeholders.

We’ve organized the results of the survey into four broad themes below.

Print vs. Digital

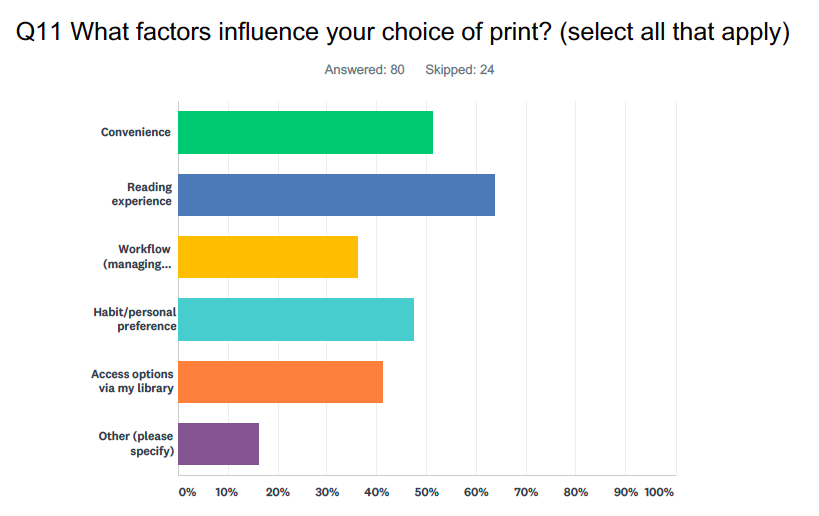

Why do some researchers abhor digital and favor print, or vice-versa? The classic print vs. digital debate was necessary for us to understand readers’ preferences with each format.

Unsurprisingly, there was no clear winner, with 46.25% saying “it depends.” Their choice of format depends on the task at hand:

“For cover-to-cover reading I much prefer print; for annotating, searching, and referencing during writing, I much prefer the digital.”

When prompted about why print was the preferred format for “immersive” reading, a respondent said, “Reading online simply does not allow for a deep, reflective, thoughtful, and active reading experience.” According to some, print works allow readers to conceptualize the work in its entirety, in a way that is not possible online. Others noted that the kinesthetic experience of a print book contributed to their preference of this format:

“The embodied reading experience is, I think, the biggest factor. Reading something long on a device feels disembodied; it’s hard to remember where I was last; it’s hard to remember reading it at all, later on. Digital works great for searching and scanning, but for multiple serious paragraphs, it feels abstracted.”

As the respondent above noted, deep reading using digital formats is still a challenge. Many respondents admitted to skimming content in digital form, and printing sections out later to read more thoroughly.

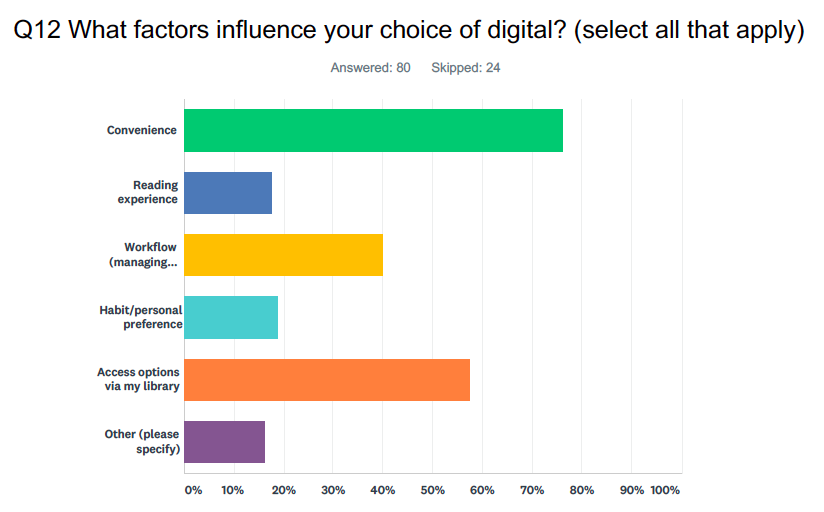

While print was a choice for many for an initial thorough read, a number of respondents turned to digital formats during the writing stages of their research projects. They praised the quick, easy searchability of digital formats, the ease of copying text into their working documents, as opposed to typing this in manually, and the portability of digital files.

Others noted that digital files, if prepared properly, were more accessible than print books:

“Since I am blind, I have scanned print books, making my own digital files. When monographs are available digitally, this saves me a labor-intensive step. However, it only helps if the files are designed with accessibility in mind. I often have to print out an image-only PDF and scan the print pages to make an accessible file.”

Overall, respondents concluded that print and digital formats are “complementary tools; one is better for retention while the other is better on grounds of searchability.” Along those lines, respondents made requests to publishers and librarians:

“We need to lobby bookstore chains for discounted ebook version[s] when purchasing hard copy. They should make a bundle available.”

Managing Collections, or Organized Chaos

For researchers who are juggling a multitude of projects at a given time, keeping track of the books in their collection is crucial. One respondent shared their frustration with managing ebook collections:

“I now have hundreds of Kindle books. Amazon provides exactly ZERO useful tools for managing them. I fought with them a couple of weeks ago to ask them if there was a way I could just download a complete list of what I have, print it, and sort through discussing it with my wife, who shares the account, and then delete many obsolete ones. THERE IS NOT A WAY TO DOWNLOAD OR PRINT A COMPLETE LIST OF WHAT YOU’VE GOT.”

Some admitted to forgetting which ebooks they owned, resulting in the repurchase of these books. Overall, we found that most respondents used a number of organizational tools to manage their collections. Some kept track of print books in an online bibliography, which they continuously updated. Another respondent noted that they use a “combination of apps which have varying degrees of features and accessibility—Zotero, Onenote, Foxit, Docear, Qiqqa.”

This combination of tools was fairly common for managing digital PDFs, EPUBs, citations, primary sources, and other materials. Respondents shared the following tools: Google Drive, Dropbox, Zotero, Mendeley, Papership, Endnote, Onenote, Foxit, Docear, Qiqqa, as well as flash drives, and storage space on their personal computers.

These mechanisms are similar to those described by our interviewees, and appear to be a system that each reader has honed over a number of years. A new collections management system would need to not only accommodate the variety of materials, in different formats, that a scholar has gathered over the years, but also be simple to use and customizable to fit the needs of the scholar. Looking toward this type of system, a respondent wished,

“It would be nice to have a software to collect materials from multiple databases in one place and to link the relevant materials together using my own organization structure.”

Interoperability of Citation and Annotation Tools

As evident from the section on collections management, researchers use a variety of tools for citation and annotation. These include: Zotero, Google Scholar plugin, EndNote, RefWorks, Mendeley, BibTeX, Bookends, Docear, Qiqqa, Hypothesis, Kindle built-in tools, Adobe built-in tools, MS Word built-in tools, GoodReader, PDF Expert, Weave, Diigo, Papership, iAnnotate, and DocuWiki.

Respondents expressed their frustration at having to resort to multiple tools to work with different digital formats.

“No one has yet invented a native-to-digital format that facilitates scholarly reading, e.g., endnotes, cross-references, annotation to an external standard format. Drives me absolutely nuts and is the main reason I’m doing this survey, because you might be thinking the same way. The ebook formats we have are functional if you are reading a murder mystery — as functional as a papyrus scroll. They have not yet advanced to incorporate the advantages of the codex book.”

The lack of “interoperability” between the tools was brought up by other respondents. The “lack of integration” and “absence of systematic annotation” systems that aggregate easily with one another poses a challenge for readers, who simply want to be “centralizing everything and [accessing] it all in the same place.” One reader notes that there’s also a challenge in keeping up with newer versions of tools:

“Citation management tools keep changing, which makes it hard to keep training materials up to date.”

In addition, readers also noted the challenge of accessing files from different computers, or in different formats, where page numbers might not correctly align with their existing notes.

Respondents also noted the challenge of implementing a single standard or tool, as it could not fit all needs (ideal though this might sound):

“For instance, Hypothesis can be a great way to annotate all sorts of things (and, somehow, keep ad hoc collections through tagging) but the Open Annotation standard has yet to be widely adopted. In an ideal world, all the full-text content from my research materials, notes, annotations, Open Data repositories, and personal files would be part of the same database structure, with proper mechanisms for classification, linking, and reuse.”

Restrictive Access: Lending Periods and DRM

The survey results revealed that access to monographs also greatly impacted readers’ behaviours. Lending periods and DRM stood out as the key factors.

Respondents observed that lending periods varied greatly for print vs. digital books.

“For a print monograph a faculty checkout period at my library is one full semester. For a digital copy it’s one to fourteen days depending on vendor.”

Readers find themselves forced to check out digital versions, as fewer print copies are held in libraries. But they are made to “return” the digital copy far sooner than they would be expected to return the print copy. These “artificial limits on borrowing periods” prove challenging for library patrons, who are simply trying to complete their reading.

“I don’t like having to ‘check out’ an ebook repeatedly to finish a close reading.”

For researchers, being able to transfer content easily across devices, or sync a number of annotation tools, is critical. DRM can prevent this ease of transfer, and even prevent readers from copying and pasting quotes from books into their research papers/working documents. One respondent said,

“DRM is the No. 1 reason digital reading isn’t my default. I want to be able to put the text on whichever devices I want and have a common set of annotation tools that sync annotations across devices. Kindle’s environment is getting decent at this, but I’m still locked into Kindle’s platform, and many/most scholarly monographs I have access to through my library are only available on platforms like Ebook Library.”

Readers wanted to remove DRM to bridge the gap between print and digital formats. A respondent said, “I would love it if print books were sold with instant, DRM-free digital access (or, conversely, if digital copies sold with very affordable access to print-on- demand).”

Conclusions

This survey has provided additional insight into the needs of readers, and, significantly, other members of the publishing ecosystem. It has shown that researchers use a range of different formats in the course of their work, all of which need to be accounted for in the tools they use. In the case of citation and annotation tools, we must work towards integrating with existing software, as opposed to creating our own. The results reinforce the idea that digital tools cannot be developed with a view to replacing print formats, but rather, must be built to supplement the same.

As one respondent put it, open publishing ecosystems are the way of the future:

“Closed ecosystems are a deal-breaker for me, as they should be for all academics, since they are prima facie violations of academic freedom and the general project of innovative scholarship – which should not be enclosed in high walls!”