7 Radio Broadcasting, Podcasting and “Superbug Media”

“We thought we were doing this little experiment, and it became this huge thing.” — Sarah Koenig, host and co-producer of the Serial podcast

Podcasting Echoes the rise of Broadcasting

The Serial podcast is a true crime drama that calls into question the efforts of Adnan Syed’s defense attorney as well as several elements of the case against him. Syed was convicted of murdering his former girlfriend Hae Min Lee in January 1999. The podcast analyzes, among other things, the use of a questionable timeline and questionable witnesses by prosecutors as well as the failure of Syed’s defense attorney to use a witness who could have provided him with an alibi. As of 2018, Syed expects to get a new trial, but listeners are split on whether Syed is guilty. Among other issues, the podcast questions whether Syed’s alibi would hold up in court. The story was released in serial fashion (that is, one piece at a time), in the autumn of 2014. Listeners were enthralled. This podcast more than any other helped establish the platform, and advertisers learned that podcasting could be a viable mass medium.

The ability to engage with murder mystery stories is not new. Serial dramas have appeared since the early days of mass book publishing, but basing a podcast around a real-life murder adds an element of voyeurism that makes some question the podcast’s social impact. The reporting was journalistically sound, but what happens when online audiences dissect real tragedies? Such podcasts are potentially dehumanizing for the story’s subjects even as they show the platform’s potential. The social and cultural reach of podcasts now rivals that of radio. It is a broad reach indeed.

This chapter discusses the history of radio broadcasting including its potential as a tool of propaganda, the relationship between radio and the music industry, the social reach of broadcasting, as well as the rise of podcasting. Finally, persevering podcasts have something to teach us about how to make successful digital products and brands.

Radio’s Reach

Radio is more than the music or “talk” you are stuck listening to because your auxiliary cable shorted out. It is a means of transferring great numbers of messages, most of which are created and disseminated by professionals, to large audiences. Radio does more than entertain and inform mass audiences. It enables other industries (such as shipping and delivery services) to work efficiently. The technology serves police and other first responders, as well as various military functions. This is not to mention the cultural aspect. Pop music on the radio was for almost a century the soundtrack of American life. Across the world, people make a tradition of gathering around their radios to experience the World Cup, particularly in areas without reliable satellite television or broadband internet service. Historically, radio was the most reliable medium to experience global events. Listen to this update from the 1986 World Cup in Mexico and imagine what it might have been like to experience the game from half a world away. The power of radio broadcasting is to connect people instantly across vast spaces. As a broadcast medium, it helped shape modern society and culture. Radio brought huge audiences together to listen to the same programs at the same time and made it possible to sell airtime, which would not exist without the medium. In other words, radio created what is now an $18 billion advertising industry out of thin air.

Radio Propaganda

Radio created a market where there had been none, but there is a downside to the reach of broadcasting. Radio’s mass appeal and quick adoption in the developed world made it possible to influence the public opinion of whole populations at once. One of the most disturbing uses of radio was to spread Nazi propaganda before and during World War II. With the technology, the Nazis could reach across national boundaries and try to gain sympathy in German-speaking communities across Europe. The Nazis also made it illegal to listen to broadcasts from other countries, particularly Great Britain. Broadcast technology has the power to influence and mobilize masses of people, but it is important to reiterate the limited effects paradigm (covered in Chapter 3). Several cultural and social forces have to be at play for messages in the mass media to help mobilize people to commit genocide. While radio can be used as a propaganda machine, people still have to believe the propaganda. Mass media broadcasting is a tool. It can be used for good or ill, and the conditions and proclivities of the audience affect the level of influence the broadcast media can exert.

Broadcast Technology

Radio waves can transmit sound and speech. Radio communications have helped direct ships and armies and win world wars. Broadcast radio intended for mass audiences created a need for information that was not present before. With radio, news can be instantaneous. People heard about developments in World War II as they were happening, which was not possible only decades earlier during World War I. Some thought this would bring an end to war because people would be too close to the pain and devastation of large-scale conflict to have the stomach for it. This proved to be an insufficient deterrent.

World-altering promises are made with the introduction of almost every new mass medium. Similar things were promised with the dawn of television and the spread of home internet access. James W. Carey calls the notion that communication technologies will bring about peace and understanding the “rhetoric of the electrical sublime.” New communication technologies do not lead to social utopias. They are both beneficial and disruptive.

The technology of radio followed the development of the telegraph. The world was already connected. Telegrams communicated complex messages in series of dots and dashes, but by working wirelessly, radio seemed more like magic. In recent generations, the spread of wi-fi internet access and wireless electrical charging give some sense of what it felt like to experience wireless radio for the first time. With the development of small, cheap batteries, the transistor radio brought rock-and-roll wherever the audience wanted to go. Radio made the instantaneous transmission of mass messages portable.

In the early days, though, radio receivers were prohibitively expensive and large. They were pieces of furniture that, for the most part, only wealthy early adopters could afford. David Sarnoff, who led the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) and later NBC, was one of the first to envision commercial broadcasting. He was instrumental in the development of commercial radio receiver production. It was necessary to generate demand first. In the early days of radio, broadcasters tried all sorts of things to make use of this new medium. Plays, opera performances and live music performances were broadcast.

As radio receivers became household items and radio broadcasts became more reliable, radio broadcasters (the large ones in particular) demanded better industry regulation. In the United States, regulation favored commercial outfits over public broadcasting. In other countries like the United Kingdom and France, regulations gave the government more control and responsibility for reaching audiences. To this day, public broadcasting is still more popular and influential in Western Europe than in the United States. Listen to this BBC Radio documentary about the Beatles to get a taste of British public radio. In the U.S., Regulation of the airwaves by the Federal Radio Commission (FRC) and later the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) helped settle who would broadcast on which channels, but the most powerful broadcast towers in the world are of little use if people do not tune in.

According to Vinylmint (also linked above in reference to David Sarnoff), the marriage of recorded music and radio came after radio had become a popular medium for delivering live music and the Great Depression had killed the value of many record companies. Three developments helped to establish the ratio as a popular, immediate, in-home mass medium: the development and promotion of affordable radio receivers, the popularization of radio through broadcasting live music and radio dramas, and the marriage of the recording and radio broadcast industries.

Broadcasting’s Influence on Recorded Music

In the early 20th century, sheet music was more popular than recorded music. When sheet music was shared widely, certain songs gained popular status. This is what defined pop music from the 17th through the 19th centuries. The radio was invented around the turn of the 20th century with contributions by Guglielmo Marconi and Nikola Tesla, among others. Then, in the 1940s and 1950s, pop music as we know it was born. Much of pop music in America was first performed by black artists and was then appropriated by white artists. Blues, jazz and rock-and-roll music all originated in black American culture. There is a long history in pop music of artists from a dominant social group taking someone else’s cultural expression and profiting from it.

Different types of music have qualified as pop music throughout the 20th century. Jazz, rock-and-roll, psychedelic rock, R & B, disco, glam rock, metal, grunge, rap, electronic dance music and other forms too numerous to categorize have all qualified as “pop” and have often competed with one another for dominance. Changing technologies drove changing tastes. The addition of the electric guitar, synthesizer and computerized sampling are just a few key developments of the 20th century. Radio broadcasting brought technological advancements in sound into homes, and the recording industry relied on radio to promote sales so that people could own the music that was most meaningful to them. The disruption that altered the recording industry is covered in Chapter 6. Podcasting did not disrupt radio broadcasting. In fact, podcasting in some ways revives radio traditions, such as the successful radio personality, the for-profit news and talk show, and shows with a deep appreciation for niche music. In the late 2010s, the most profitable content on broadcast radio is conservative talk radio. It is bombastic and often mean-spirited, but it is popular among a relatively powerful sector of society: older, white men. Podcasting opens up avenues for all manner of expression. The audience for a podcast selected at random may be small, but in the aggregate, there are millions of listeners, and this platform for audio communication is growing with young audiences just reaching the age where they have some disposable income.

Podcasting

The term is derived from blending “iPod” and “broadcasting,” although Apple no longer manufactures the iPod and most podcasts are not broadcast over the airwaves. Because alternative terms such as “mobile audio blogging” do not exactly roll off the tongue, “podcasting” remains in popular use. Podcasting can be traced to the popularity of blogging in the early 2000s. Bloggers wrote about niche topics, and some of them developed sizable followings. Podcasting is in some ways a natural extension of this form of direct communication with organically cultivated groups. It caught on with wider audiences in 2004 as broadband internet penetration increased rapidly and as more and more people owned iPods or iPhones capable of storing and playing back several episodes at a time. Expectations for podcasting as an industry rose and fell for about a decade until 2014. This article in Wired notes two important occurrences that year. First, the Serial podcast demonstrated podcasting’s ability to reach beyond niche audiences to become a truly national media phenomenon. Second, Apple created a separate iPhone app dedicated to downloading and listening to podcasts, which help boost the prominence of the entire field.

Many of the top podcasts are National Public Radio shows rebroadcast or repackaged in podcast form, but several successful shows originated as podcasts. This list of some of the top podcast episodes of all time draws from a wide variety of topics, including health, money, mindfulness and communication. Like magazines, cable television and niche news sites of the past, podcasts often develop in niche environments. Only a tiny percentage reach mass popularity. Here is one of 2018’s top podcasts about the state of the War on Terrorism. You can find it online as part of a visual presentation, on iTunes or via other podcast apps. The methods of accessing podcasts vary widely. Even novice smartphone users can find podcasts through popular apps. Podcasts rise to popularity by word of mouth or by reaching enough critical mass that they are referenced in other media platforms. We often learn about live music based on which bands are popular locally and regionally. Instead of being organized geographically, podcasting is often organized by topic. Comedians, talk show hosts, academics and other experts, scientists, engineers, philosophers, writers, musicians and many others have podcasts serving various functions. Their podcasts may or may not be promoting other products, services or digital media properties. They may be fiction or non-fiction. What links the vast majority of podcasts is they begin as passion projects. They are cheap to produce and free to download, and they grow niche audiences before, sometimes, making it big. Podcast advertising will soon be a $500 million industry. Observations on what helps a podcast thrive can teach us the keys to success that we expect will translate to a variety of emerging digital media platforms.

“Superbug” Media

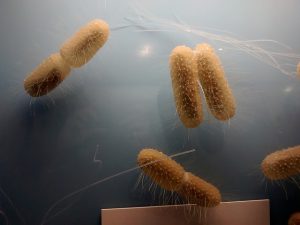

Podcasting as a medium seems to have stumbled on a sort of “superbug” model of mass media production and audience building. Think about bacteria and our unending desire to kill them with anti-bacterial soaps, wipes and hand sanitizers. Only the strongest, antibiotic-resistant bacteria survive attempts at eradication. Successful podcasts function similarly. Those that survive the media free-for-all often build mass audiences rather than tapping into them on legacy media platforms.

Superbug media products are the opposite of viral media. A virus develops and spreads via a host, and if it does not spread to another host relatively quickly, it dies. Either the host system kills it, it kills the host, or it leaves the host and dies. Generally speaking, viruses do not work in symbiosis with their hosts. We can vaccinate ourselves against viruses, and this happens with viral media messages too. If we view a new video on social media with some of the elements of viral videos we have seen before, we may ignore it. We inoculate ourselves against things that waste our time. Novelty is part of the joy of viral content. Thus, copycat content has a difficult time spreading. This makes audience-building on digital platforms difficult. You cannot reliably produce viral content. Exponentially more media products are created than go viral, no matter how hard the creator tries.

The “superbug” process is different. Bacteria can often survive without a host. They can lie dormant for years with very little to sustain them and then return to devastate populations. In the human body, there are about as many bacteria cells as there are human cells. Some bacteria are not only beneficial but also necessary. Bacteria can be localized, while viruses tend to attack an entire system. The media equivalent of successful superbug bacteria is a podcast that grows inside a niche population, sometimes rising and falling in popularity before reaching a mass audience who then looks into the back catalog to see what the podcast is all about. What follows is a summary of the nascent theory of “superbug media.” For now, it is a list of characteristics that will be explicated to conclude this chapter. This is not a media studies theory arrived at through extensive peer review. These concepts are meant to describe phenomena that appear to be happening all around us. Over time, the author hopes to publish more about this topic and begin to test these concepts as a cohesive theory built on empirical facts. That said, here is the working definition: Superbug media products are those that survive and thrive in highly competitive environments with limited initial access to traditional media resources. They are persistent, adaptive, independent, niche and symbiotic.

- Persistent

Media creators should expect to be producing a podcast or other form of a superbug media product for a year before it becomes recognized. Audiences expect good, consistent, free content as a starting point when selecting which media products to adopt and support. To have a chance at long-term survival, a potential “superbug” media product should be published at least weekly. A mix of regular themes combined with fresh guests, topics, and additional media content appears to work best. Another feature of persistent “superbug” media is that they fend off challengers. You never really know how many people are researching a certain area or producing podcasts or apps in a particular field until you try to produce your own. Often, there are many market players you were not aware of. Some may operate in “regions” of the network society or intellectual community. It is your job to know the field and to know the competition from the outset when you are striving to create a “superbug” media product, such as a podcast, a web application, a smartphone app, a niche advertising agency, a PR firm or a news agency. Whatever it is that you make, your brand needs to be ready to fend off both existing and up-and-coming competitors.

- Adaptive

Successful podcasts and other “superbug” media products adapt to new environments. They may start out as audio podcasts but later become video posts because the content demands it. They may begin with interviews or content displays from people in the producers’ close circle and then expand to bigger names and better content as the development of the media brand progresses.

- Independent

Potential “superbug” media products often begin as independent productions from makers with personal passion. That is, they start out almost entirely as products of culture and only later, with time, success and reinvestment, do they begin to resemble institutional productions that are designed for long-term survival and capable of helping their producers and owners to thrive. Some “superbug” products, brands, and even platforms might emerge from existing institutional production houses or even major corporate conglomerate media companies, but they must be given the freedom to adapt if they are to last long. This raises a question: What defines success for a superbug? There are, perhaps, three tiers of success. The first is when a “superbug” project breaks even and no longer costs more to produce than it makes. The second is when it earns enough money to reasonably support one person for a year, which is a major milestone. The third tier is when the project earns enough money to warrant hiring a number of people and occupying some space in the physical world. What has been described here might also be thought of as the process through which a cultural product becomes part of an institution.

- Niche

Growing mass audiences is different from reaching ready audiences in “legacy” broadcast settings. It helps to begin by focusing on a niche audience with the potential for mass appeal. The choice of topic is a personal one; however, what differentiates future commercial efforts from passion projects is the consideration given to market potential. Consider the topic of strategic landscaping planning: A podcast or app dealing with the issues faced when trying to manage a common household yard might grow to reach millions, whereas a podcast about formal French gardens will probably start in a niche and stay there. Neither media product is broad, general interest news, but one fits a more narrowly-defined niche. If it is your goal to produce something for your cultural passion, you can work in whatever niche interests you; for something to qualify as having “superbug” media potential, there must be plenty of room to grow.

- Symbiotic

For many “superbug” media products to ultimately reach success, they will need to join with other independently produced brands or allow themselves to be swallowed and possibly rebranded under the umbrella of a large conglomerated media company. Symbiosis comes when the small, upstart media product and the larger “host” corporation help one another to grow. Often, a large media company will have money to invest in updated equipment and marketing, but for every Beyoncé, there is a Destiny’s Child. The process of entering into a symbiotic relationship changes both the host and the “superbug.” This might be unappealing from the aspect of pure cultural production, but on the other hand, it is often helpful and necessary from the institutional point of view. Again, creators are free to produce their passion project online, but the descriptive theoretical definition of “superbug” media is that it survives and goes on to thrive in a hostile environment.

An easy way to remember this material is that it takes PAINS to build an audience on a digital platform. Cultural production is at the heart of much of what we do in the mass media, but institutional demands are never far behind for those who want to create successful products or for those who may not want to make their own “superbug” media outlets but who are looking for good places to work.

The final lesson of this chapter is this: Regardless of whether you plan to start your own media product or create a “superbug” of your own, when looking for work in the mass communication field, you owe it to yourself to look for companies that are capable of producing products and brands that can survive in this environment. At your internships and your first jobs, ask yourself if the company seems like it could produce a “superbug” if it had to. If the answer is “no,” you may need to look somewhere else for an enterprise that can create a media product with that rare mix of cultural meaning, social impact and financial success.