4 Film and Bricolage

“Walt Whitman once said, ‘I see great things in baseball. It’s our game, the American game. It will repair our losses and be a blessing to us.’ You could look it up.” — Annie Savoy, played by Susan Sarandon, from the film Bull Durham

More than Merely Movies

The LA Times did look up the reference quoted at the end of the film Bull Durham and found that Whitman’s sentiments were represented more or less accurately. What appears in the film is a distillation of a longer paraphrase—made by Horace L. Traubel, a noted Whitman biographer—of a statement Whitman probably did make. The line in Bull Durham captures the essence of the quote, even if it is a paraphrase of a paraphrase. This is often what great films do. They take what is available in reality and distill it down so viewers can understand it the first time. When you make a copy of a copy, things get blurry, more difficult to decipher. Films often do the exact opposite with elements of culture. They reduce present reality and essential past experiences into distilled intertextual products—mediated messages that combine various types of text into one.

A movie combines moving pictures (video, film or animation), sound, graphics, special effects and, of course, written text, which is most often spoken as dialogue. It can be delivered as a disembodied voice speaking over video in what is called a voice-over, or text can appear in graphic form as actual text on screen. Each element from video to sound to graphics and special effects is considered a text. The various texts are sewn together in a multi-layered story.

Movies are popular because of the stories they tell and the way they tell them. The most popular films have a compelling narrative, fantastic special effects, great cinematography, supportive, realistic sound effects and often a great score. Compiling and combining texts for mass audiences in major motion pictures is incredibly difficult to do well, but with digital technology, many millions of people can create intertextual stories on their own.

Whether you are a YouTube producer or enjoy making Instagram stories every day, you can be an intertextual storyteller with tools readily available on the mass market. The “readily available” part calls to mind the concept of bricolage, which in intertextual storytelling means taking the images, sounds and words readily available to you, along with the recording and editing tools that are also available, and making stories intended for others to appreciate.

This chapter covers the film industry and bricolage together to emphasize that all mediated messages, whether they are an individual’s latest Instagram production or a major motion picture studio’s latest multimillion-dollar gamble, are exercises in bricolage.

This chapter first discusses film as an industry and as a modern mass media platform. It goes on to examine the potential cultural influence of filmmaking and the implications of this potential for filmmakers. The chapter unpacks the concept of bricolage in the context of filmmaking. Finally, this chapter considers the role of passion in crafting messages for mass media audiences.

Filmmakers are some of the most passionate, creative people in the mass media industry. They balance knowledge and skill in managing many types of media production. At their best, they are enthusiastic about storytelling and about professionally mastering many aspects of the art form. At their worst, filmmakers (including producers, directors and others in the industry) are controlling manipulators who apply their efforts recklessly and for personal gain. There is a reason some of the worst outrages leading to the Me Too movement happened in the film industry. It is an industry where powerful people, usually men, have for too long used their power to do awful things without repercussions. This issue will be addressed before the chapter’s conclusion.

A Brief History of Film

This section draws heavily from a text called Movie-Made America by Robert Sklar who points out that popular films in America were the first modern mass medium. Since this text considers the penny press the first mass medium, it will be necessary to clarify. The penny press arose around the end of the First Industrial Revolution. By the 1830s, many people in newly-developing nations had left the agrarian life and moved to cities to work for wages in some form of manufacturing. The penny press was identified as their mass medium because large numbers of people consumed the same newspapers at an affordable cost. They shared collective narratives about what was happening in the world that editors considered important. (Readers were privy to the agenda-setting function of the mass media; however, the penny press was often a regional mass medium. Different city, different paper.)

Fifty years later, the Second Industrial Revolution progressed with advancements in the textile, steel, automotive and war industries, which continued through World War I and World War II. Sklar argues this industrialization made the film industry viable. After working 10- or 12-hour days to keep up with demand and to make enough money to survive and perhaps thrive, people were looking for quick, easy and relatively affordable entertainment. Motion pictures shown on big screens in theaters built for sizable audiences fit the bill.

What made filmmaking a mass media industry was the ability to show the same film to large audiences again and again. Films also presented a new way of telling stories. Early filmmakers experimented with the art form and actively sought to make their work different from anything that had come before. In art and culture, a purposeful break from the past is one way of defining modernity. Thus, film was the first modern mass medium. The very first movie parlors, however, were not capable of projecting film.

Early Moviegoing

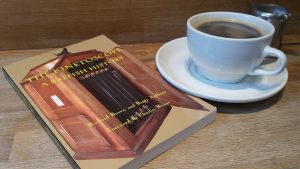

According to Sklar, when the film industry arose at the turn of the 20th century, films were first exhibited as short motion pictures viewed in kinetoscopes. In the image of the kinetoscope shown in this chapter on a book’s cover, you can see an open cabinet. Inside the cabinet is a long, winding film. To watch a movie, you would lean over the top of the closed cabinet and peer into the viewfinder. It cost a nickel. Most often, immigrants and working-class people frequented nickelodeons, which is what the parlors and theaters housing kinetoscopes were called. In the United States, film brought American culture to immigrants and immigrant culture to other Americans in an exchange that helped foster social change.

The Developing Movie Industry

Nickelodeons were not profitable enough to sustain the industry in the long term. Recognizing that showing films was more profitable when movies were projected for many viewers at the same time, filmmakers rushed to create films that looked best in that format. When film was taken out of the box and projected on large screens, it opened up the medium to become the mass market industry it is today. From the perspective of theater owners, it was better to show one film from one protected projection machine to an audience of paying customers than to have people fill up a parlor and wait in line to climb on top of the equipment one at a time. As film became a mass medium, concerns over content and the medium’s potential to influence public opinion grew.

Movie Ratings

In the 20th century, producers quickly learned that motion pictures could be the most powerful propaganda tool in the world. By bringing modern messages to mass audiences, films were (and still are) able to shape public opinion through culture. Their reach extends beyond influencing trends: Films are massively popular emotional and educational cultural products that can influence the shape and direction of social structures.

Early on, messages in the medium were not subject to government or church approval, which concerned the leaders of these institutions. The battle for control over the industry has never stopped. The current rating system used in the United States is a voluntary system. That is, the government does not censor films. The industry regulates and censors itself through the maintenance of a movie ratings system, which is not without controversy.

Because films can have massive economic, cultural and social impacts, it should always be expected that powerful groups will try to exert their influence over this medium.

Movies and Culture

There are dozens of journals that examine the relationships between film and culture. Films influence popular culture, group culture and just about everyone’s personal culture. If your professor or instructor were to name an abstract emotion, a major industry or a popular sport, you could probably think of a film that deals with that aspect of culture or society. Think about gender norms, religious sensibilities, economic inequality, gay rights, militarism, environmentalism, family values, popular history, patriotism, cultural violence, liberty, race, global technology, artificial intelligence or sheep farming. There is a movie for almost every group culture. Social issues often drive filmmakers, but they may also pursue stories about popular issues to attract the broadest possible audience. Filmmakers often balance the desire to highlight the social and cultural issues they care about with the need to make money in a global cultural industry.

Filmmaking Practice

The American film industry employs more than 2 million people, according to the Motion Picture Association of America. Filmmakers and studios are protected by the First Amendment to discuss almost any topic they choose. The marketplace is often a more limiting factor than other forms of social or cultural influence. Many great stories are not made into films because it is too costly to produce a major motion picture to risk box-office losses. It is the right of the film studio to pursue profits, but many filmmakers consider their work a vocation or calling. The driving artistic and economic forces often compete wherever movies are made.

Filmmakers today gain experience by making commercials, music videos, television shows, independent movies and even web series posted directly online. Young filmmakers rarely work with actual film. It is far more expensive to shoot film than video. The most common format at the time this book is being revised is SD (secure digital) media. The file type and codec depends on the camera. Many filmmakers shoot video on DSLR cameras and enjoy the ability to switch lenses for different conditions or effects. This type of media can store large files, and in the future SD storage may increase as high as 128 terabytes per card. As video quality increases, so does the need for greater storage capacity. Video formats such as 4K and 8K are known as ultra high definition. They enable filmmakers to capture and show incredibly detailed images.

Successful filmmakers not only have to know the tools of the trade, but they must also be good at networking. Films may cost up to a billion dollars to make and to promote. Filmmakers must demonstrate they can work well with others before a studio will take such a large chance on their talent. Because so much social and cultural influence and financial risk rest on a few flagship films each year, the controls are generally only given to proven filmmakers. To truly represent the voices of women, minorities, immigrants and other cultural groups in our society, there need to be pathways in the industry to producing, directing and promoting major films. For example, even before news broke about the many women who have been sexually assaulted in the industry, Hollywood had drawn mass attention for problems with industry sexism. Perhaps for the industry to be a better place for women personally, it needs to be a better place professionally. For this reason, there must be a variety of industry entry points if Hollywood is truly going to offer diverse points of view told from diverse groups of people. An entry point is a position in an industry that an individual can use to gain the experience needed to move up the career ladder. All of the technical skill in the world is of little use if there are not pathways to powerful positions.

Storytelling

Filmmaking tools and practical career preparations give options and opportunities to professionals, but they do not make films better by themselves. In other words, a technically skilled filmmaker might still fail because the industry is about storytelling. You might like a film with great special effects more than you like one without any, but the development of a new special effects technology does not make every film that employs it a good one. You can probably think of a bad movie with relatively good special effects (Spoiler alert: Lots of Michael Bay). Likewise, there are great classic films with almost no special effects. The tools are only as good as the people wielding them.

As suggested, films can play an important social and cultural role. They can communicate political agendas and can push issues to the forefront of media attention. Filmmakers and studies, on the other hand, may also go out of their way not to make political statements. Whether a film communicates directly or more subtly, the most successful films combine great technical skill with a combination of trusted and innovative storytelling techniques.

A key goal of movie marketing is to make people anticipate a film so much that they feel they have to see it on the opening weekend for fear of missing out. For people who do not often go to movies, one key indicator they use to judge a film’s success is its rank at the box office. It takes the support of both regular movie fans and those who only see a few films a year for a movie to be a true blockbuster. The best and most successful films combine great technical prowess with innovative but approachable storytelling. The best filmmakers have to be able to get professional work out of hundreds or even thousands of people working on a single project. They must be able to manage actors, special effects crew members, film crews and marketing professionals, to name a few. Filmmakers must also have a sense of the interplay between texts. The best storytelling is multifaceted and emotional but sufficiently connected to reality to be relatable.

Bricolage

Every motion picture that succeeds at being intertextual — that is, every film that combines a variety of types of text into a tapestry for audiences with a good story behind it — is a matter of bricolage. The term “bricolage” is related to the French word for “tinkering” and calls to mind the word “collage.” Most readers of this text will have made several collages in school with the idea being to create art or to depict a concept using available materials rather than drawing or painting something from scratch using a single medium. Bricolage refers to a do-it-yourself tinkering process where you make something new out of other things.

You might argue that new films are made with new technology, not existing film clips or video files. You might also point out that special effects, 3D projection, and IMAX technology are not cheap, and the materials to make modern blockbusters are not going to be found simply lying around. You would be correct if movies were only storage media they are shot on, the computers they are edited in, and the 3D glasses you wear in the theater. But in reality, every film is made with limited resources using the existing tools and the talent available at the time. Every film is, to some extent, a pastiche, a reference to the films that came before. Bricolage is about taking the tools, materials and talents available to you, tinkering with them and making something different that has its own meaning. It is like a college student making dinner from leftovers. Turkey and Swiss cheese with pancakes for bread? Why not? Throw some chili on it. Wash it down with a light beer. Bricolage.

Some bricolage is better than others. Major motion picture filmmakers do a kind of bricolage. They simply have more expensive tools. Often, it is said, films are written three times. First, the script is written. Then the film is shot and brought to life by the director, actors, film crews and effects crews. Finally, a film is rewritten in editing. This notion that films are written as scripts, revised in the shooting process and written a third time in the editing booth comes from this video summarizing how the original Star Wars was saved in editing. Filmmaking is a collaborative, iterative process, which means it may take many people many tries to create a successful story.

The Limits of Passion

Some students will be impressed by Quentin Tarantino’s assertion, “I didn’t go to film school. I went to films.” It is tempting to think that all you need to know about filmmaking can be learned by watching films. That is certainly the start of developing a passion that can drive a career, but there is a case to be made for a formal education.

College is where you learn how to think strategically. You learn how to work with other professionals-in-training. Working through college for four years or more, you gain stability and personal connections. You may not all end up as filmmakers or mass media professionals, but the critical thinking and problem-solving skills you learn from a liberal arts background prepare you to evaluate sources of information. You learn how to ask where people selling you a story got their information. If you learn how to learn, how to analyze media critically and how to make your own work as professional as possible, you will be prepared for shifts in the industry that might otherwise sap your passion.

Passion is like a pit bull. It can be a friend, companion and protector — something to rely on when times are tough. Passion that is mistreated, ignored, or that knows only about the darker, more violent side of life, can get out of its owner’s control. There is no specific, perfect formula for cultivating your passion. Choose one and apply it in every college course you possibly can. If your education works for you, your passion can be tamed and it will always with you.

Before he was known as a screenwriter and before he had directed anything, Quentin Tarantino was doing more than just watching movies. He worked with people who made films. His work at a production company enabled him to get his script for True Romance to film director Tony Scott. Without his production company experience, no one would have cared that he knew everything there was to know about kung fu movies and westerns. He would have been a very knowledgeable video store clerk in a world where video stores were about to die.

So Wrong for so Long

When Uma Thurman talked about Harvey Weinstein’s attempts to sexually assault her, she told a story dozens of other women shared about Weinstein’s abusive, criminal behavior. The prevalence of sexual assault in Hollywood was a driving force behind the global Me Too movement of women as well as men sharing stories of sexual assault and abuse. Abusive behavior, mostly on the part of men in the workplace, has been tolerated in Hollywood and in other corporate and institutional cultures for far too long. Sometimes it was even joked about. Most often, it was allowed to be part of the business of entertainment.

In a better future for film and other forms of media making, sexual assault would not be tolerated, and people of all genders and backgrounds would support each other against those who abuse their power to reinforce their dominance and for sexual gratification. Laws did not do enough to protect women from predators, but speaking out has started to make a difference in a culture that has tolerated harassment, abuse and rape. For the film industry to truly be one of free expression and thoughtful cultural and social meaning-making, it cannot be a place where more than half of society is objectified and dehumanized regularly.

Uma Thurman also noted in her opinion article about Harvey Weinstein that she was objectified to the point that Quentin Tarantino pushed her to risk her life when shooting a car chase scene. Her story was about sexual objectification and assault but also about the way men, in particular, devalue women in many aspects of life. If Hollywood can change, its stories change too and the social and cultural impacts of that movement would be felt like waves emanating from this time for future generations.