3 Media Literacy and Media Studies Research

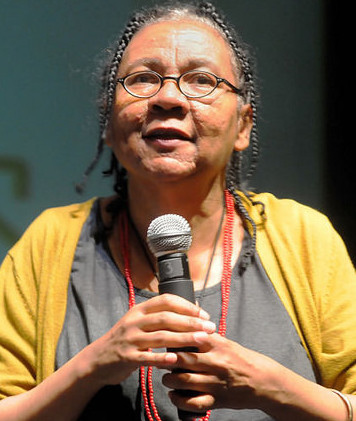

“Understanding knowledge as an essential element of love is vital because we are bombarded daily with messages that tell us love is about mystery, about that which cannot be known. We see movies in which people are represented as being in love who never talk with one another, who fall into bed without ever discussing their bodies, their sexual needs, their likes and dislikes. Indeed, the message is received from the mass media is that knowledge makes love less compelling; that it is ignorance that gives love its erotic and transgressive edge. These messages are brought to us by profiteering producers who have no clue about the art of loving, who substitute their mystified visions because they do not really know how to genuinely portray loving interaction.” — bell hooks from her book All About Love: New Visions

The Academic Approach to Studying the Mass Media

If you have been reading the chapters of this text in order, by this point you will be aware of the powerful role the mass media play in society, but you may not yet question whether society benefits from this arrangement. In general, the mass media could do a better job of representing all sorts of groups and group cultures. The mass media could also represent abstract concepts like love, trust and greed in more meaningful ways. This is not to say that the mass media have failed in this regard, but there is much room for improvement.

As active audience members, as hybrid producer-users or “produsers” (to use a term coined by Axel Bruns), you must not only be selective but also critical of what you consume. Whether you become media professionals or not, it will ultimately be your job as media consumers to remake the mass media in ways that better represent the depth of human experience.

Whether your interest is a religion, a fandom, or an abstract concept like love (one of the greatest of abstractions), you have the power to participate in the media production redefining how others understand it.

No, this is not a book about love. Yes, love and related concepts are commodified in the mass media; however, the disruption that has echoed in political spheres and often in the ways family and cultural group members speak to one another about politics also opens up space for critical thinking. That is, the same disruption described in Chapter 2 that allows for social upheaval also allows for a time of reflection and critical thinking about how society and its media function.

This chapter gives you some tools developed by mass communication scholars to develop your critical eye when viewing messages as products in the mass media. If massive numbers of “produsers” can reshape the media landscape, we have to re-think the role of mass media professionals. Assisting people in the process of meaning-making — that is, making mass media with audiences instead of for them, and aiding them in their own communication efforts — could open up a new purpose and new industries for those who are mentally prepared and daring enough to take the lead.

This chapter defines “media literacy” and touches on some key mass communication theories that are absolutely not meant to be left to molder in the digital cloud where this text”book” lives. Take these theories out, apply them and see how they work. Find out how useful they can be and what their limitations are.

This text presents an image of entire societies and cultures swimming in a sea of media. Consider these concepts your first set of snorkel and swim-fins.

Media Literacy Defined

Media literacy is a term describing media consumers’ understanding of how mass media work. It includes knowing where different types of information can be found, how best to evaluate information, who owns the major mass media platforms, how messages are produced, and how they are framed to suit various interests.

In a global society that gets most of its information through digital networks, it is incredibly important to know how and by whom media messages are made so that as consumers we can discern how the mass media are being used to shape our opinions. We can reply to or comment on messages in the mass media, or we can demand a seat at the table when messages are being constructed. This is the nature of participatory media outlined in the previous chapter. Being media literate gives us the tools to participate well and with purpose.

It is important to consider your role in contributing directly to mass media content. Your contributions to cultural trends and social change in the mass media can sometimes happen without your knowledge. If you post regularly to Facebook or other social media platforms, your data are being aggregated, and that information is used by advertisers, researchers, and news services to find out what you like and what you are like, as well as to create ads and political messages tailored just for you.

You are more than your preferences and the media you consume. You are encouraged to play an active role in shaping your digital identity beyond the one that has already been created for you.

Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is media literacy put into action. Besides contributing to the creation of meaning by making your own mass media messages (perhaps in collaboration with professionals), you can ask who owns major mass media corporations. Scholars have found that more than half of the mass media channels available to mass audiences in America are owned by only five corporations or firms.

My own research, conducted with two research partners in graduate school, has shown that just by making people aware of the nature of media ownership, you can encourage them to be skeptical of mass media content.

This text has already established that mass communication is what makes society in the physical world work. Information, often in the form of messages in the mass media, permeates institutional interactions and passes between all of us in our homes and schools and businesses. The information conveyed in the mass media gets interpreted in organizational, group and interpersonal communication contexts. These systems influence each other, but mass media messages tend to envelop and permeate other forms of communication. Thus, if you learn to be skeptical of the information you receive in the mass media, you learn how to critique the whole global social system.

Critique this Book

Reading closely, you will have undoubtedly found value judgments in this text already. You may be inclined to assign political values to this text in our hyper-partisan cultural environment. You are welcome to do this. You are encouraged to do this. You must think critically about the cultural values expressed not only in this text but also in your other textbooks and in the history and literature you read.

But you also must think critically about your preferred media outlets. Where do they get their information from? Who owns them? No single revelation about the mass media will tell you everything you need to know. You have to begin to see nuance and to think for yourself what aspects of the mass media matter most to you, what things you think should change, how you might change them, and what you can live with.

It is part of the responsibility of citizens now to critique messages that come to us via mass media, as well as messages from leaders who bypass mass media gatekeepers and fact checkers. It is also a sound career strategy for those who go into the mass communication field to learn to be able to critique messages, messengers and owners in the corporate mass media field of work and play. To know where the mass media industry is headed, you must be able to think critically about where it comes from.

Much of the rest of this book breaks down different mass media channels and looks briefly at the history of how each came to be, what and whom each channel serves, and how convergence in a digitally networked society might affect the future of each medium. This text also returns several times to “big picture” questions about the dynamic relationship between media and society as seen from the perspective of the various mass communication channels and platforms.

The Dichotomy Between the Media and the “Real World”

For nearly the dozenth time in this text already, your author has referenced a “dynamic.” The mass media reflect our social norms and expectations and, dynamically, they shape our norms and expectations.

To the extent they are shaped by mass media, our perceptions of reality are very much artificial — but not entirely so. How artificial is too artificial? Different individuals and different cultures differ in the amount of nonsense they can tolerate.

The real challenge to us as young media professionals and scholars is to try to determine what is artificial in the vast array of messages delivered to us at all times by the mass media. One of the best ways to do this is to get off of social media platforms and talk to people in person. We should also dig a bit into the information we consume and ask, “How do they know?” Whenever a message comes to us from a mass media outlet or from a friend’s social media post, the media literate individual seeks to know what underlies each claim.

The question is not whether you believe it. The question is: On what grounds is a message in the mass media or in social media believable?

Now that people are constantly using technology and even wearing it, it is becoming more difficult to separate messages mediated by professionals, who pledge ethically to adhere to disseminating factual information (such as most journalists), from poorly-supported, opinion-only content or outright misinformation, which may be spread far and wide by friends and family.

We are living in a media age where we may not trust our own family members’ social media posts. Things they think are important might not only be unimportant to us, they might be distasteful or even wrong. There are real-world consequences to sharing misinformation on social media platforms. Question the sources’ sources. Talk to people in tangible spaces apart from social media platforms, and you can learn to see what is supported by fact in the physical world and its digital networks.

The Bad Dynamic

Your media choices matter. In the network society, when mass media content is ubiquitous on mobile phones and is often projected into public spaces, it can be difficult to differentiate between your independent preferences and the opinions you are encouraged to carry by advertisers who constantly bombard you.

Without human interaction outside of the deluge of electronic information, it can be nearly impossible to figure out for yourself if what you like is a response to the quality of the media content or if you are responding to carefully targeted marketing campaigns.

The system of checks and balances in which you can compare your real life experiences to what you see and hear in the mass media may break down. A pessimistic view is that we may enter a constant state of depression on a social level because we are cognitively incapable of comprehending all of the information presented to us and we lack ways of taking regular “reality checks.”

Feelings of isolation and inadequacy coupled with cognitive overload create the potential for a host of social issues. Additionally, the images we see in ads and the perfected versions of themselves people present on social media usually do not reflect applied critical thinking.

The “bad dynamic” that comes into play is one where glossy identities are carefully constructed and protected while our real identities rapidly disintegrate. We may establish a society where many people have identity issues, and those issues are constantly worsening. It may seem at times as though we are headed for a massive collective mental breakdown.

What good is media literacy? Thinking critically about the mass media and content spread on social media helps us critique constructed images and accept our own shortcomings. If we look for ways to relate to one another besides our overlapping common culture interests, we may find deeper connections are possible. We can share imperfections and tackle doubts, but only if we acknowledge them in our media world first.

What follows are a set of mass communication theories arrived at through the analysis of facts and data by thousands of scholars over the course of nearly 100 years. As an academic field, mass communication is young, but there are several theories, or guiding abstractions, that can help us to see how our society is structured and what roles the mass media play in society at all levels.

Critical Media Theory

There are many critical theorists among mass communication scholars. They work to develop better analytical theories that teach us how to analyze messages in media systems and the mass media and help us to discuss with clarity what is beneficial and what is harmful to society.

Academic work is about digging deep. Scholars will often analyze one medium at one period in time to explain how certain groups or ideologies are depicted.

Marxist critical theory questions the hierarchical organization of society — who controls the means of production and whether that control benefits society or only small groups of people. Every society has and needs leaders, and one of the most important functions of society is to manage a functioning economy. At question in Marxist critical thought is how the rules of each economy, including the global economy, are set up. Do they benefit most people? Do they allow for merit to be rewarded? Do they create a system of fair competition? Are they set up for collaboration and mutual benefit?

Most scholars who apply critical theoretical models would hesitate to call themselves Marxists. Marx was both a scholar and a revolutionary, a term which academics rarely self-apply. Most Marxist critical thinkers suggest changes that society could make to be more inclusive and fair for a greater number of people, but what is fair will always be debated. There is no single line of Marxist thought. There is a small number who demand complete change in the global economic system, and there are thousands of critical theorists calling for more narrow or specific changes based on their observations in their areas of expertise — not just mass media analysis but all kinds of social analysis.

Historically, Marxist thought has been employed by dictators, often using mass media channels, to take power and often to wield it in horrendous ways. Marxist thought also guides the reasoning of some mainstream economists who help manage social democracies, which historically garner more good will than dictatorships. Scholars working with the critical theoretical point of view often note broad ways for society to improve as well as practical solutions that might help (although getting leaders to listen is another matter). Making cogent arguments and convincing people to hear them are very different things.

That said, ideas about questioning hierarchies and asking for whom social systems really work are still central to modern critical theory. This is what Marxist critique in media studies is all about: looking at symbols and underlying messages in all forms of media and discerning what purposes they serve, and asking whether they represent exploitation, corruption or any other social ill often found in closed hierarchies.

Symbolic Interactionism

Another critical theoretical perspective is symbolic interactionism. The general idea comes from George Herbert Mead and suggests that people assign symbolic meaning to all sorts of phenomena around them. Our behavior is guided and influenced by our perceptions of reality and the symbols around us.

Mass media extend and limit our senses. When our senses are extended, we can become overwhelmed by the amount of information coming in, so we look for symbols, and we categorize ideas according to those symbols to make the messages easier to understand.

We sometimes apply the symbols ourselves, but in many (or even most) cases, the people editing messages in the mass media purposefully use symbols as a shorthand way of communicating. Not everyone understands every symbol or perceives them the same way. Symbols have a cultural context, but this is not much of a limiting factor in American society where there is a vast shared common culture and targeted marketing can tailor which images to deliver to which individuals.

You are encouraged to think critically about the symbols you see and ask whether they are meant to manipulate you. We will not stop using symbols in communication; however, if you ask, “Why am I being shown this symbol at this time,” you can take a practical step in critically analyzing media.

An example would probably help.

When asked to come up with an advertising campaign, college students often select a familiar category of beverage: energy drinks. RedBull uses the symbol of wings to show that an energy drink can pick you up and help you to move more quickly through your work. You can fly where you had stumbled. But that is not the only reason associate wings with Red Bull. Wings are a symbol of angels, saviors, and other powerful beings. If an individual has reservations about consuming something that may be unhealthy, moral symbolism and images of power are designed to subconscious guilt or misgivings.

It is up to you to critique images in the mass media as you see fit, but you should develop the skill and practice applying it.

Agenda-Setting Theory

Agenda setting is one of the most simple mass communication theories to understand, and it is one of the most widely cited.

It argues that the mass media tell us what to think about. In other words, the mass media help people to set their own agendas.

The idea is not that mass media companies come up with a specific agenda and then preach it to the masses; rather, mass media outlets learn what people are interested in and find similar topics based on what has been learned in the past. Then, the messages that appear in the mass media tell audiences what topics they should care about and how to prioritize them.

This is a dynamic process, and there is no evidence of a singular media agenda. All one needs to do is to flip through cable television news channels to see vastly different points of view presented to mass audiences at all times.

Instead, agenda setting highlights certain topics and stories and those topics become the public’s agenda based not only on what appears in the mass media but what people accept, care about and share more widely.

Messages in the mass media may or may not succeed in directing us how or what to think, but with great success, they tell us what we should be thinking and talking about.

The examples are easy to find. Many mass media outlets talked more about Ebola during October of 2014 rather than the midterm elections. People came to discuss Ebola more often than the elections despite the fact that the election might have a more direct effect on them than Ebola ever would. The assumption may be that professionals in the mass media are pushing an agenda about a scary world, but in most instances, they are promoting news they know people care about based on previous responses to similar topics.

For an agenda to be set, messages have to appear in the mass media, and they have to be accepted by massive numbers of audience members. The acceptance of messages in the mass media is known as salience. Here is how agenda setting theory works: Various mass media outlets have agendas for coverage that they develop. It may take years for a film company to develop a brand. News organizations change their coverage agenda several times a day. An agenda is just a list of issues a media outlet wants to discuss and a prioritization of those issues.

Research has shown thousands of times that those agendas are passed on to audiences. This is tested by surveying people about what issues they think are important and comparing that list to the issues that had been in the news and entertainment media in the weeks before taking the survey. The topics and the relative levels of priority are often (but not always) passed along.

Agenda setting still works even as the processes of de-massification continues, but the influence of mass media outlets may be diminishing. The theory is based on the assumption that there are mass audiences all consuming similar messages, but mass audiences are diminishing. That said, the messages people share on social media between one another often originate in mass media channels.

Gatekeeping Theory

Gatekeeping theory describes a practice where a person acts as a filter, deciding what information will be disseminated for public consumption via the mass media. A good example is an editor in a news organization looking at many stories from a newswire.

Newswires put out hundreds of stories per day. The same newspapers that publish wire stories from other areas may contribute stories to the newswire if something interesting to a broader audience should occur. Only a handful of wire stories make it into a TV news broadcast, onto a newspaper’s website or into the paper itself.

In television news, producers act as primary gatekeepers. Only a dozen or so national and international news stories make it into the average big city daily newspaper, where the task falls to an editor. The person with the job of selecting and editing wire stories for a news organization has to decide which news stories are noteworthy to the local audience. The practice started in the 19th century with the marriage of the telegraph to the newspaper, and it continues as text, images, video and information graphics are shared through digital networks.

The way gatekeeping works has changed significantly over the past two centuries. Now, we often think of gatekeepers guarding a gate with no fences because on the internet anyone can post almost anything. Mass media news outlets are no longer people’s only major source of news and information about the world. Social media platforms carry both messages produced by both mass media outlets and individuals free to share almost whatever they like online. Of course, sharing something online does not guarantee it will be popular. There are plenty of YouTube videos with very few views.

And where there are mass audiences, there is still plenty of gatekeeping going on. Humans do much of the work planning what goes into major newspapers and network news broadcasts as well as entertainment products for that matter.

On social media platforms and in search engine content, however, the task is increasingly managed by algorithms — sets of procedures or rules for computers to follow.

In the future, we expect to see fewer human gatekeepers and more gatekeeping work done by recommendation engines and the like. You are unaware of the full extent of Netflix’s available content because you only see what your preferences suggest you should see. The same is true for Google searches and advertisements pulled from databases filled with vastly different ads designed to target different individuals at precisely the right time.

There is also a new theory to be aware of that concerns the flip-side of gatekeeping. “Gatewatching” describes people who consume all sorts of news and other information and who stay current with new information as it arrives. It is as though they are watching professionally produced media messages come out of the gate and then almost immediately these media consumers post links to Reddit, Twitter, Facebook or other social linking sites and social media platforms.

Gatewatching is when someone takes a message already published, by professionals or amateurs (but more often by professionals working for mass media outlets), and shares it for others to see. It is not uncommon on Reddit to see stories from the national and international media ranked alongside funny cat videos and random thoughts people had in the shower. On the one hand, putting the power of gatewatching in the hands of users is a way for people to set agendas for one another. On the other hand, information-as-popularity-contest can promote biased views and can shut out not just what is politically unpopular but what people consider to be boring, which severely narrows the scope of discussion.

Try to consume mass media or social media for a day without seeing or hearing about pop music stars, Kardashians, major sports figures or odd news from far-flung places. It is a challenge, even if you tailor your social media experience to avoid trending topics.

Framing Theory

Framing is a basic mass communication theory with widespread implications. It suggests that the way a news organization (or an entertainment producer, for that matter) frames a story is purposeful and meaningful and can influence how people think about the topic. A news frame refers to the way a story is presented including which sources and facts are selected as well as the tone the story or message takes.

An example is the period leading up to a war. If the United States has plans to go to war, it can be framed as a risky proposition, a patriotic endeavor or a morally righteous thing to do.

For any major news story, there are usually a few dominant frames that emerge. The author of this text was a television reporter at the time of the buildup to the Iraq war, and our station framed the issue as a matter of patriotism. There were patriots and there were protestors. Our station built a “Wall of Heroes” to display photos of marines, soldiers, airmen and sailors killed in action. While any given story about the buildup to the Iraq war might have been objective, the decision to build a display wall framed our coverage in a certain way. The display remained on view for approximately 18 months. The station then stopped keeping track in that highly visible, demonstrably patriotic way, even though the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq continued for 15 more years on a reduced scale.

Whether you agree or disagree with the idea of remembering those who died in Iraq through local television news broadcast tributes, the point is that stories are framed by how they are covered. It matters what sources are selected for news stories and which sources are left out. It matters which terms are used and how prevalent they are. Framing analyses delve into news content to identify various themes and to show which ones receive preferential treatment.

Surveys of news and entertainment media consumers will reflect which frames were most salient; that is, not only which stories but also which frames stay in the minds of audience members.

Limited Effects Paradigm

A paradigm is a collection of theories from the social sciences, which are themselves collections of facts supporting an abstract idea meant to explain the phenomena of human behavior. A theory is supported by empirical facts. It’s not the same as when your buddy shotguns three beers and says “You know…I have a theory.” Social scientific theories are meant to be big ideas that help predict behavior or the results of certain behaviors.

In the field of mass communication, the limited effects paradigm is so-called because there are different kinds of theory relating to different media that all show the same thing: It is a complicated task to tie one set of messages to massive shifts in human behavior. Even small shifts in behavior like deciding to purchase one smartphone over another are only partially influenced by messages in the mass media. There are simply too many other factors influencing behavior to say that a certain set of mass media messages caused behaviors across a mass audience.

Influence is another matter. The mass media work in tandem with other social stimuli to influence all sorts of behavior. If there were no influence, there would be no reason for mass media advertising or government propaganda. It is because they work that both are a constant presence in the global mass media environment. At question is how much influence certain messages can have and under what conditions is the influence stronger or weaker.

The limited effects paradigm started as a response to theories such as the hypodermic needle theory. After Germany lost World War I, mass communication was just starting to emerge as its own discipline. One of the first theories American scholars of mass communication had was that propaganda infects a population like a needle injecting a viable virus into the body.

Scholars thought that propaganda turned Germany into an imperialistic, nationalistic country (that is, Nazi Germany), but propaganda never works that easily. When the Nazi Party unified the country between World War I and World War II, a large portion of the population, welcomed the shift in social policy, despite the accompanying racism and violence. It did not take as much convincing for many Germans, as many in the aftermath of WWII and the Holocaust would like to think. Using many kinds of authority, the Nazis committed atrocities. Mass communication enabled it, but the theory that propaganda could, more or less by itself, create that kind of situation has not held true. There were social weaknesses and social structures in place that paved the way for the Nazis, who could not have risen to power by media influence alone.

This does not mean that the mass media have no effects. It would not make sense to argue that communication permeates society and then to suggest that it has little to no effect on people. What the limited effects paradigm suggests instead is that information does not sway people as often as it is assimilated into existing patterns of thought. And those patterns of thought are shaped by all sorts of social forces, not just mass media campaigns. To reiterate, other social forces at play include religion, family, education, economic status, health, crime and incarceration.

Changing people’s minds is difficult. Motivating behavior is difficult, and there are many variables guiding human behavior. Thus, the core concept is that the mass media have limited effects on society. Small effects are measured in mass communication studies all the time, and influencing thoughts is generally understood to be easier than influencing behavior.

Limited Capacity Processing Model

The Limited Capacity Model of Motivated Mediated Message Processing (LC4MP), which we’ll call the Limited Capacity Model for short, is a theory that states that our cognitive abilities are limited, so we are unable to process all of the information that we see, hear and read.

Since we cannot perceive and understand everything, parts of our brain act as filters that either disregard information, very rapidly process it according to our long-held assumptions, or force us to pay attention to it. We can force ourselves to pay attention to information as well, but it is difficult (which you might notice while reading textbooks).

The theory goes deeper than this and explains how we process information when we do attend to it. The three stages are encoding, storage and retrieval.

Encoding is when you voluntarily or involuntarily pay attention to a message and its underlying symbols.

Once attention is paid, a message can be stored, or, recorded in our memories. Not all messages are easily retrieved, or, recalled when we wish to remember them.

Some are retrievable only in part, or they may be altered in the storage and retrieval process. There are voluntary and involuntary types of encoding, and what we store and how we store it has a lot to do with what is already in our minds. It is generally easier to store something when it connects to familiar thoughts.

All of this amounts to a quantitative approach to studying memory in the context of mass media messages. It does not presume effects.

In fact, since a message has to be encoded, stored and retrieved before it can influence behavior, the limited capacity model is part of what explains the limited effects model.

Even if we had all the useful information in the world, our brains could not store and use it all. Thus, even the best advertisements, political campaigns and in-depth news documentaries are up against the limits of our minds.

Keep this in mind as you think critically about the messages you see and share.