10 Advertising, Public Relations and Propaganda

“What you call love was invented by guys like me to sell nylons.” — Don Draper, fictional advertising executive from the AMC series Mad Men

Think Critically about Where Persuasion Becomes Propaganda

Advertising is a relatively straightforward process, right? Companies develop brands and specific products they want to sell. They need to make consumers aware of their brands, products and those products’ features, so they develop creative campaigns to promote them and often pay ad agencies to do the creative work and place the ads in front of mass audiences. The basic definition of advertising is a message or group of messages designed with three intentions: to raise awareness in the population about brands, products and services; to encourage consumers to make purchases; and, ultimately, to inspire people to advocate for their favorite brands. A brand advocate is someone who is so supportive of a product or service that they publicly encourage others to buy it. There are paid brand advocates, of course, but in a networked communication environment, even unpaid individuals with modest followings can become influencers — people who promote products on their social media streams. Consumers who have been so successfully persuaded to purchase and enjoy a product that they try to persuade others to buy it too extend the reach of advertising potentially exponentially.

A company is a business entity that produces several types of product, whereas a brand is a term used to label a specific product or a limited family of products. It is important to differentiate between the two. For example, PepsiCo owns the Pepsi brand but also Frito Lay, Gatorade and Quaker, among others. Under the Pepsi brand, there are several products such as Diet Pepsi, Pepsi Wild Cherry and many other variations around the world. Advertising most often focuses on brands and products rather than the companies and large corporations that own them.

As this chapter progresses, it defines the core concept of advertising in more depth. Then, it discusses the history of advertising. It defines two general strategies or approaches known as “above-the-line” and “below-the-line” advertising before examining in detail the “advertising funnel,” or “purchase funnel.” A few other basic theories are introduced. There are sections on content marketing and other forms of persuasion. The big picture of marketing is briefly addressed before the chapter concludes with sections on public relations and propaganda.

Advertising Defined

On one level, advertising is a simple concept. Mass media professionals craft messages to help sell products by raising awareness and pushing people to make actual purchase decisions, but in the network society and the age of targeted marketing, the ability to reach individual consumers who fit precise sets of characteristics is incredible. More is expected of advertisers than to put interesting messages in front of the “right people” based on general demographics. Brands may advertise during certain TV shows or publications to reach a particular type of media consumer. This more traditional form of mass media advertising is still a multibillion-dollar industry, but with data-driven targeting capabilities, brands can reach people based not only on general demographic characteristics but on specific behaviors as well. The combination of detailed demographic information, search and digital media usage behaviors and physical world behaviors (such as whether someone has entered a Walmart or Macy’s in the past week) makes advertising in the information age more powerful, sometimes more meaningful and often more ethically questionable than in the past. The level of targeting that is possible is incredible and would have been unimaginable 20 years ago. Advertising has always been about tapping into consumers’ existing needs or about creating a need and inserting a product to fill it. Now, there is a greater ability than ever to identify and create a need not only for interested members of a mass audience but also for specific individuals in real time based on their online and physical world behavior.

The History of Advertising

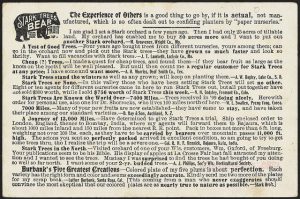

Before delving into a discussion about the future of advertising, it might help to survey the history of the field. Advertising in the modern sense emerged between the mid-19th and early-20th centuries. At the same time that the concept of brands was developing, mass-media platforms such as daily newspapers and radio broadcasts grew their audiences and spread their influence geographically. Corporations, conveniently, grew large enough to have massive budgets to spend on advertising. The promotion of products dates back thousands of years, but the modern advertising explosion tracks explosive growth in industrial manufacturing from roughly the mid-1800s through the entire 20th century.

HubSpot has a deck of 472 slides that presents a narrative about the history of advertising. Some highlights are referenced here. One key point made in this visual history is that non-branded newspaper ads would often outnumber branded ads in the early days of the newspaper industry. As uniformity in mass-produced goods became the norm and brand differentiation became possible, so did the need to communicate it.

Ayer & Son is credited with being the first ad agency to work on commission. In other words, it is known as the first modern ad agency. It was founded in Philadephia in 1869. Today there are about 500,000 ad agencies in the world of all shapes and sizes. They employ ever-evolving techniques to try to stay ahead of information weary consumers.

Categorizing Advertising Methods

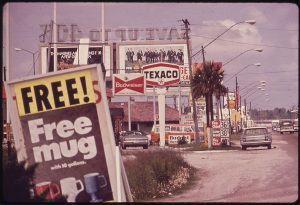

From the mid-20th century on, advertisers conceptualized their work by breaking it down into one of two strategic categories: “above-the-line” and “below-the-line” methods. Put simply, “above the line” (ATL) refers to methods of advertising that target mass audiences on mass media platforms with messages usually designed from a one-to-many point of view. Often, “above the line” implies that the ad or ad campaign — a series of related ads meant to work in tandem — appears on legacy media platforms. (Recall that “legacy media” has been defined previously in this text to refer to platforms in existence before the transition to digital.) ATL campaigns most often include television, radio and print ads as well as sponsorships. A sponsorship is when a company pays to support an event or a mass media production in exchange for having its brand promoted alongside the activity or content. The organizing concept for ATL advertising, as the term is used today, is that the ads target a mass audience primarily on “legacy” media platforms.

“Below the line” (BTL) advertising refers to more one-on-one marketing approaches which can include targeted social media campaigns, direct mail marketing, point-of-sale ads, coupons and deals, and email and telemarketing appeals. This is not an exhaustive list of ATL or BTL methods, but these examples demonstrate that ATL has more in common with the concept of mass communication introduced in earlier chapters, and BTL has more in common with interpersonal communication, also as previously discussed. This is not to say that BTL messages are crafted one at a time for individual consumers. Rather, the tone, style and method of dissemination of BTL advertising are more personal.

In the 20th century, the term ATL advertising was associated with ad agency work (mostly mass media campaign ads), whereas BTL advertising referred to pamphlets, point-of-sale marketing and other relatively “small” tasks that ad agencies typically did not handle. Now, there are ad agencies of all sizes, and even very large agencies might do BTL marketing. Online advertising and social media marketing have made it possible to target people with personal messages but still purchase the ads on a massive scale. Thus, advertising can be massively individuated — that is, produced for mass audiences but having the appearance of personalized messages — much like social media content. The profit in BTL marketing comes from reaching large audiences with tailored messages at specific times in relation to their previous purchasing and shopping behaviors. So much data exists on individual users and on the behavior of similar people who have made similar purchases that advertisers can try to target people at precisely the right moment to influence their purchase decisions.

ATL and BTL advertising can work hand in hand. Think of a summer soft drink promotion advertised on television and on the radio (ATL) that is also backed up with neighborhood-specific billboards and hyper-targeted Twitter messages with surprise prizes given out (BTL). BTL messages still reach large numbers of people, but they are by definition more tailored than ATL ads. An individual ad in a BTL context may not cost as much as a massive ad buy facilitated by an agency that primarily does ATL advertising; however, BTL advertising can still be costly for advertisers and profitable for ad agencies in the aggregate. For example, an ad agency that does not typically manage multimillion-dollar television ad buys might still put together hundreds of thousands of dollars in targeted social media ads. Rather than displaying one commercial for several months, the BTL social media campaign might be made up of dozens of targeted videos, tweets, influencer posts and online ads. Often software algorithms are used to decide who sees which targeted ad and when.

The Advertising Funnel and Other Key Concepts

At its heart, advertising is a matter of raising awareness, creating a deeper interest in a product, and encouraging consumers to desire to make a purchase and ultimately to take action. Professional communicators tailor messages in relation to the advertising funnel or purchase funnel, as shown in the image on the left. Brands, either on their own or with the help of advertising agencies, target audiences in different ways at specific points along the funnel to reach their strategic goals. For example, if an unknown brand launches a new product, people need to be made aware of both the brand and product. The brand may need to establish itself with an awareness campaign. If Nike introduces a new Air Jordan, the branding is easily handled. The top of the funnel areas of awareness and interest will not need as much focus as the decision and action areas, the “down funnel” aspects of a campaign for a well-known and well-loved brand.

Another way to think of this is as a pathway a potential customer makes, also known as the consumer journey. First, the consumer needs to be made aware of the brand and its products. Then, they might take an interest in a particular product as they learn more about its features. They need to move from being interested to desiring a product if they are going to make the purchase. Ultimately, from the advertiser’s point of view, the goal is not only to move the consumer to purchase the product but also to inspire them to advocate for the brand. This is not conceptually complicated. The idea is to move people in straightforward steps toward desired behaviors; however, there are complex processes of cognition and persuasion that underlie consumer decisions.

Consumer behavior is about as unpredictable as other forms of human behavior. There are also ethical concerns. If a product or service proves to be harmful, advertisers and public relations professionals have to decide if and when they will stop marketing the brand. Advertising is challenging enough when products do not raise ethical dilemmas. Promoting harmful products can be damaging socially, professionally and personally. Thus, the world of consumer advertising in the mass media is more complex than the funnel makes it seem, although it is an essential strategic model in the industry. There are two other advertising concepts or theories that this text aims to introduce: the basic rule of seven and the third-person effect.

The Rule of Seven

The advertising rule of seven is a rule of thumb, or what social scientists call a heuristic, which suggests that people need to see an advertisement seven times before they act on it. Even then, there is no guarantee that seeing something seven times will compel a person to buy a certain product, vote for a particular politician or take any other consumer action. Instead, the point is that consistent messaging is a base requirement for advertising to work.

The purchase decision is ultimately a personal one. You can create the conditions and increase the probability of a product being bought, but it is difficult (perhaps impossible) to predict behaviors based on messaging. Even the most successful advertising and propaganda campaigns only constitute one area of influence on behavior. As previously stated in this text, social institutions such as your family, friends, church and workplace can influence your behavior in tandem with or contrary to what you see and hear in the mass media.

The Third-Person Effect

There is a theory in the study of mass communication called the third-person effect that says we tend to think advertising is effective but we believe that it does not affect us. Note here that social science theories are based on many observable facts. This is not a flight of fancy. Rather, this is a tested theory demonstrated in multiple studies. Here is how the third-person effect works with regard to advertising: You might think upon seeing a clever advertisement, “Sure, that ad probably got someone else to buy the product, but it doesn’t influence me. I’m a savvy shopper. I don’t just go out and buy whatever ads tell me to buy. I’m not Homer Simpson looking at billboards.”

And yet we do know that advertising works at least to influence behavior. It has measurable effects on attitudes, that is, what people think about brands. Advertising influences brand and product awareness in individuals and in groups. We can say with a degree of certainty that some people are directly influenced by some ads some of the time, and we can say that many people are indirectly influenced by ads almost all of the time. For example, you may not drink Coke Zero, but you probably know what it is, and you may know that it is now called Coke Zero Sugar after a name change in 2017. Whether you understand the logic behind the name change or you actually buy the soft drink is another question. Campaigns to make consumers aware of new brands and products have a track record of widespread but still limited success.

Now here is what’s interesting about the third-person effect. Knowing that advertising can influence people’s awareness and purchase decisions, we tend to develop a sort of double delusion where we think other people are probably affected more than they are, and we think we are influenced less than we are. Sometimes we even base our behavior on what we think other people will do after receiving a message in the mass media. It works like this: We hear a message that a winter storm is coming, and we worry that other people will be easily influenced by that news. That worry and not the original message may influence our behavior. The author of the original study noted that if there is news of a possible shortage, people sometimes buy up that item at grocery stores. This has happened as recently as 2008. Rice futures went up and up out of fear that people were stockpiling rice. So, what did people do? They stockpiled rice. Costco and Sam’s Club even put limits on the number of large bags of rice people could purchase.

How does the bread and milk effect work? Following the third-person effect theory, an individual hears about a storm coming to the East Coast of the United States. He thinks that other people are going to feel the need to go out and buy up all of the bread and milk, so, aware of the threat and concerned about their behavior, he goes out and buys bread and milk. Now the concern has become a self-fulfilling prophecy. People are, in fact, buying up the bread and milk. The question is whether they are buying it up because they are unduly influenced by messages in the mass media, or they are responding out of fear of how other people will behave. You can imagine other people foolishly thinking a winter storm is going to be worse than it is and you can think to yourself you had better buy the bread and milk before those fools, but to them, you have become the fool.

The third-person effect is also a major issue in race relations and partisan politics. We often presume that we know how individuals from other groups will think because we have seen messages in the media and we presume to know how the “other” will respond. The third-person effect is based on three presumptions. First, we assume that other people have seen the messages we have. Then, we presume that they will be influenced by those messages. Finally, we presume that they will behave in certain ways because of the message and because of our preconceptions about different groups. For the theory to work, it does not matter if the “other” is Democrats, Republicans, frat bros, Mexican people, snobby professors or slacker college students. Our assumptions can be completely wrong and we may still find ourselves acting in ways to pre-empt or counteract the imagined behavior of the imagined “other.” There are different degrees of the third-person effect. Researchers have found it is probably strongest in situations where groups have little understanding of one another and where the messages and perceived outcomes are thought to be negative (note the section on Perloff). This is not to overstate the third-person effect. Like other theories related to persuasion in the mass media the behavioral influences it identifies have to contend with other social forces to influence behavior. Still, it is one of the most interesting theories in the field of mass communication, and it can explain why people race out to buy a certain product when they perceive it to be scarce. We do not want anyone to beat us to the bread and milk.

Content Marketing

Content marketing refers to a common practice where brands produce their own content, or hire someone else to produce it, and then market that information as an alternative to advertising. It still moves people along the purchase funnel, but there is usually added value in this type of content. If an advertisement for a mattress describes its features and price, a blog funded by the mattress brand might compare the pros and cons of many different mattresses, perhaps with a bias for the brand. It isn’t always pretty. Content produced for a brand should ethically be labeled as sponsored, but it is not always done. In cases when consumers have discovered that trusted sources were content marketers rather than independent reviewers, the revelations have created public relations problems for the brands. Content marketing done ethically offers financial transparency while providing valuable information and an emotional connection to the product for consumers. It can take the form of blog posts or entire blogs. Such marketing is usually optimized for search engines, which is to say the posts are written to attract search engine attention as well as outside links, which also alerts search engines that this content is valuable. Done well, branded content can be seen as more authentic than advertising content, and it can be cheaper to produce and disseminate. It is difficult to do well, of course.

The most common types of content created in this context besides blog content are social media profiles and posts, sponsored content in social media spaces and even viral video and meme chasing. Brands might have their own social media profiles, or they might support social media influencers to promote their products in a sponsored way. Brands might also use their influencer teams or their own internal marketing teams to follow viral social media trends and to create memes. In a sense, content marketing allows a brand to create a more human profile in digital spaces. In this manner, brands can engage with potential and repeat customers. Brands can foster relationships and encourage brand advocacy among people not being paid to promote their products. Many brands use this form of marketing to engage consumers on a deep level and to offer information and emotion that might not be present in other forms of advertising.

Marketing Disambiguated

The more you study the bigger picture of marketing — which includes advertising strategies and other research efforts meant to guide advertising strategies as part of larger sales and production strategies—the more you recognize how focused advertising is. It may seem that advertising is the biggest, most important element of the mass communication industry because its revenues fuel other types of mass media production, but advertising is only one piece of the marketing puzzle. Marketing’s four P’s — often described as product, price, place and promotion (or position) — encompass much more than making messages to support brands and products. Marketing professionals worry about all four and consider advertising as just one part of the promotion category. Advertising professionals will often argue that the best branding helps define and redefine the product over time so that the product only exists in consumers’ minds as advertising has described it, but marketing gets into the business of deciding what products to make, how to promote them, whom to market them to and when to stop making them.

HubSpot, the advertising company that provided the quick history of advertising early on in this chapter also gets credit for helping to popularize inbound marketing. The idea of inbound marketing is that you bring people in to learn about your product using content marketing and then you can make sales to them in the context of a relationship where they found you rather than vice versa. In a sense, inbound marketing turns advertising upside down by building spaces and inviting consumers in to find what they are already looking for rather than trying to create a need out of the glut of information in digital communication networks. Inbound marketing is advertising’s answer to de-massification. It involves developing consistent messages and content of uses that are so compelling people will come to the brand to experience them. It is the audience-building aspect of advertising. It relates in many ways to the superbug media concept from previous chapters, and it is growing in popularity as people and companies develop new and better ways of avoiding advertising.

An established method of inbound marketing is to write a blog or develop a podcast that attracts audiences who come for information and who stay for the delicious products. To fully understand the power of inbound marketing, ask yourself if you have ever become a brand advocate. Have you ever sung the praises of your new smartphone or told people they had to try a new restaurant? If you have advocated for a brand and sent people looking for it online, you have probably become part of someone’s inbound marketing strategy. In many ways, marketing (particularly content marketing) bridges the concepts of advertising and public relations because it includes content production similar to advertising and it establishes relationships with consumers, which is the ultimate purpose of PR.

Public Relations

The history of the public relations field is often misunderstood. Many think of public relations as organized manipulation made up of corporate, political and even non-profit propaganda. It is often thought of as deception, but this is not always the case. In a society fueled by networked communications, it is becoming less important to ask what messages people receive and more important to ask what messages they seek out, according to Greg Jarboe, author of a brief history of PR. Jarboe worked for a PR firm with offices in San Francisco and Boston, two of the most well-established technology markets in the country. He argues that PR is more about creating a sense of understanding between consumers and brands and that this might be done just as well by the brand in digital spaces just as it is via other mass media channels controlled by other corporate entities. Historically, PR depended on other media platforms such as TV, newspapers and magazines to promote its content. Content marketing means this is no longer the case. Mass media platforms may still be needed to reach mass audiences outside of a brand’s collection of fans and followers, but much goodwill can be generated by maintaining a proactive, positive and professional digital presence.

While it is true that PR often tries to put a good face on companies with all manner of reputations and harmful business practices, it also serves charities, governmental services and small local businesses. Not every institutional organization can have a huge PR budget, but the practices can be taught to just about any small business owner.

The History of PR and Propaganda

At the core of PR is a simple model developed by Harold Lasswell in the 1940s. Developing an effective PR model was an important war effort during World War II when it was essential to develop theories for how propaganda worked to determine what the Nazis were doing and, if possible, how their propaganda could be stopped. Lasswell’s model asked five simple questions: who (Sender) sent what (Message) through which channel (Channel) to which audience (Receiver) and with what effect. This was a way of breaking down mass influence beyond advertising. In a sense, governmental propaganda is PR, but the client is a country. The S-M-C-R model (often attributed in that particular configuration to Berlo) is the most efficient model for understanding how to break down and analyze messages in the mass media.

Professionals and academics examine and manipulate all four components to isolate which changes correlate with which behavioral effects. S-M-C-R assumes that the sender comes first and the receiver comes last. There is a time element that must be established in researching the effects of mass-mediated messages, but the point is that this simple model of propaganda became the basis for all sorts of media effects studies. Propaganda and PR messaging does not work immediately to bring about drastic changes in behavior. Behavioral phenomena, particularly changes in behavior, are driven by many variables, as we have discussed several times; however, if you want to begin to look at an advertising campaign, film or news documentary to examine its effects, this is the model to start with.

Noise must be accounted for, and in an age dominated by the digital information glut, the opportunity for immediate feedback and engagement must also be considered. Receivers almost immediately become senders in a network. Thus, the S-M-C-R model will often include measures looking at how much noise gets into the system and looking at what happens when receivers immediately start their own S-M-C-R processes. Wherever a message originates, even if it is as simple as clicking “Share” on Facebook, the S-M-C-R model starts again.

More Concepts in PR

For most of the 20th century, the shorthand definition of PR was that it was like advertising only instead of paying a media outlet to run a message, you sent the message out to journalists and other gatekeepers (see Chapter 9) in the hopes that they would share the information as news. Now, PR has to work in a digital media system where news reporters and editors are not the major gatekeepers deciding what information will be made public. PR professionals now need to think about search algorithms, search engine optimization, social media trends, social media platform algorithms, social media influencers and social link sharing sites such as Reddit. Publicity on these channels can be worth tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars. PR often measures its worth in earned media — the amount of free air time on TV or space in major newspapers and magazines that is earned by getting other mass media channels to tell your product’s stories without having to pay for ad space

An example of earned media is when Apple released a new iPhone, and news organizations provided coverage of the lines that wrapped around city blocks as people waited for the latest gadget. For years, Apple earned millions of dollars in earned media by keeping new features a secret and then releasing new iPhones with considerable hype. Free marketing time and space in digital and print publications can help push a brand from being a leader to being legendary. Global PR is a $14 billion industry.

PR can take the form of an event, a product placement, or a skillfully crafted message delivered during a crisis. It is much less about promoting specific brands and more about promoting and maintaining the image of a brand, company or large corporation. Recall that advertising tends to focus on brands and products. PR can focus on the company and the corporate narrative, the story of how the company came to exist and how it represents certain values and ideals — at least in theory.

Sometimes it helps us to understand an element of mass media if we discuss when it all goes wrong. When British Petroleum (BP) had an oil gusher erupt in the Gulf of Mexico on April 20, 2010, after the Deepwater Horizon oil rig exploded, 11 people died, and more than three million barrels of oil leaked into the gulf. It took almost three months to cap the oil gusher. The CEO of BP, Anthony Bryan “Tony” Hayward, lost his job because he made a major PR blunder when he said he just wanted his “life back.” Eleven people were dead. The fishing and tourism industries of Louisiana, Mississippi and parts of Texas, ravaged by hurricanes just years before, were being threatened again. This time, though, Mother Nature was not to blame. It was BP, a multinational corporation that up to that point had been working to create a more environmentally friendly image. It took BP years to come back from that disaster, and it was made worse because of poor crisis communications. PR is about promoting good relationships with your consumers, your employees and the communities where your products are made. It is about earning “free” news and social media coverage, but perhaps most importantly it is about managing crises so that people are not given a reason not to buy your products.

Crisis Management

The best way to build good PR is to carefully maintain a good reputation over time and to avoid behaviors as an individual, company or corporation that might harm others. The best prevention against bad PR is to follow your industry’s and your own ethical codes at all times, whatever they are. Even if you do this, you might face a PR crisis. For example, a politician might decide to target your brand regardless of whether your business practices are ethical. All the more reason to maintain good longstanding relationships with your consumers.

The first rule of crisis communications is to plan ahead by anticipating the kinds of problems your company might have. Chemical companies should prepare for chemical spills. Sports teams will probably not prepare for environmental disasters, but they may have to prepare for the social media scandals that players sometimes land themselves in. If there is a disaster, the advice is to “be truthful and transparent,” to not say too much and to correct any exaggerations that emerge in the news media and on social media, within reason. Engaging in social media arguments is almost never productive for a brand, unless you have Wendy’s level of Twitter clapback. A major goal of PR efforts during a crisis is to try to make people forget there ever was a crisis.

Journalists often have the opposite interest because reporting on conflict is interesting. Helping people to survive is one of the primary functions of journalism. This explains why negative news gets so much more attention than positive news. No one dies when people do their jobs salting the roads and drivers maneuver safely in snowstorms. When people crash, that, sadly, is news. Journalists know that people care about safety perhaps more than any other issue, so they focus on safety concerns during times of crisis. At these times, PR and journalism can be at odds, but truth and transparency are still advisable to the PR professional. You do not legally have to tell journalists everything that has happened (depending on the circumstances and whether your institution is funded by taxpayers), but if journalists discover a negative impact that you failed to disclose, they will wonder what else you are hiding, and they may give your critics and detractors extra consideration and attention.

PR professionals work to manage story framing. (Recall that framing was defined in Chapter 9.) PR pros often work with journalists to cover negative stories with clarity and honesty rather than trying to hide the facts about a crisis. Finally, in PR there is the need to learn from mistakes and to analyze a company or corporation’s crisis responses. As difficult as it might be to go back and discuss where communication failed, it is essential. Reflection is a critical step in learning and corporations are like any other social institution. They need to learn to survive and to thrive.

PR Wars

Besides the conflict during crisis situations between journalists and PR professionals, there are PR battles that go on between competing brands and between non-profits, corporations and government officials all the time. Lobbyists make demands on politicians but also push agendas on mass media and social media platforms. In an age of digital communication, it is cheap and easy to develop detailed, professional messages employing a variety of media types that PR pros can try to spread around the world instantaneously. You should be aware as an information consumer that there are ongoing battles for your allegiance. Corporations engage in PR combat all the time, though they often try to work undetected. This is not to claim conspiracy or to frighten readers. It is simply a matter of fact that PR efforts are ongoing and that attacks within these battles do not always take the form of headlines. They may come in the form of messages from Twitter bots, botnets, collections of fake social media profiles run by software or blogs, or email spam.

You can influence other people by what you read and share, and you are encouraged once again to be aware of where your news sources get their information. Read and think before you share. It has become easy for individuals and fake accounts to publish information into the world’s information glut. Twitter and Instagram followers and Facebook friends can easily be bought. Major political influence is now wielded by fake accounts working to drum up anger and to promote misinformation to sway public opinion. Individual information consumers must take responsibility for their own consumption and for what they spread. Your media health is as important as your sexual health. Protect yourself and those you share information with.

What you need to be able to do is to consider a source, consider how it is presenting its message, and consider the source’s sources. Media literacy is about what enters your mind: what stays in (that is, what is salient) and what goes out. We are all publishers now. Media, society, and culture will always influence you to some degree, but they are also yours to try to control. Mass audiences may be in decline but entities who know how to build mass networks of users and how to successfully, if not always ethically, use their information are only starting to show their power.