6 Chapter 6: Foodborne Illnesses

Brandye Nobiling

Chapter Objectives:

- Recognize the social toll foodborne illnesses have on society.

- Identify the most common types of food linked to foodborne illnesses.

- Identify the most common infectious agents responsible for foodborne illnesses.

- Identify how to prevent foodborne illnesses as a consumer.

- Identify how food can be contaminated during production and distribution.

- Explain how agencies work to identify and report foodborne illness outbreaks.

Introduction

Foodborne illnesses (FBI’s) affect millions of people living in the United States each year. Out of approximately 48 million cases, nearly 130,000 result in hospitalization and 3,000 result in death. In addition to the health toll FBI’s have on society, there is also a large economic cost. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) estimates that FBI’s cost the United States 15.6 billion dollars a year. This chapter discusses the most common types of FBI and how to prevent and control FBI’s at various levels.

Types of Foodborne Infections

According to the CDC, five infectious agents cause the majority of FBI cases, hospitalizations, and deaths in the United States. Salmonella is the second most common cause of all FBI cases and the leading cause of FBI-related hospitalizations and deaths. Norovirus is the most common cause of all FBI cases, the second most common cause of FBI-related hospitalizations, and the forth cause of FBI-related deaths. Clostridium perfringens, Campylobacter, Toxoplasma gondii, E. coli (STEC) O157, Listeria monocytogenes, and Staphylococcus aureus are also common causes of FBI cases, hospitalizations, and deaths. Click here to see the full table on p. 2 of the fact sheet.

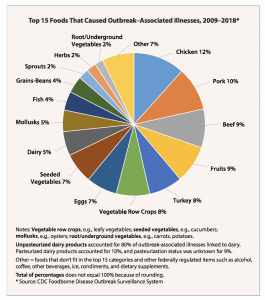

What foods make us sick? Unfortunately, some of the healthiest foods are most often linked to FBI. Foods like animal protein sources and fresh produce are not highly processed foods and do not have many preservatives. As a result, they are more vulnerable to be infected with bacteria, viruses, and parasites. The pie chart in Figure 6.1 breaks down the most common foods linked to FBI’s.

What is the difference between foodborne illness and the stomach flu? There is a consensus in the scientific community that there is no “stomach flu”, and that if someone has symptoms such as diarrhea, vomiting, stomach cramps, and fever they are most likely suffering from an FBI.

Infectious Agents that cause FBI’s

The CDC has linked most cases of FBI to a finite number of infectious agents. The majority of these agents are bacterial, but viruses and parasites also cause FBI’s. Table XX outlines the most common types of FBI’s.

Table 6: Common types of FBI’s

| Infectious Agent | Foods Linked | Signs/Symptoms | Treatment | Complications |

| Salmonella (bacterial)

|

Poultry, beef, pork, eggs, fruits, sprouts, other vegetables, nut butters, frozen chicken foods (e.g. nuggets) | Stomach cramping, diarrhea, vomiting, low-grade fever. Symptoms clear up within a week. | OTC remedies (e.g. Imodium) for relief. Antibiotics only for severe cases. | Reactive arthritis

|

| E. coli (bacterial)

|

Beef, sprouts, spinach, lettuce, ready-to-eat salads, fruit, raw milk, and raw flour and cookie dough. | Stomach cramping, diarrhea, vomiting, low-grade fever. Symptoms clear up within a week. | Antibiotics should not be given. OTC remedies (e.g. Imodium) for relief. | Hemolytic uremic syndrome, the main cause of kidney failure in children |

| Norovirus (viral) | Leafy greens, fruit, and shellfish Also transmitted through indirect contact with vomit or stool of infected person | Stomach cramping, diarrhea, vomiting, low-grade fever. Symptoms clear up within a week

|

Antibiotics should not be given. Drinking fluids to prevent dehydration.

|

Dehydration, especially in older adults, immuno-compromised individuals, and pregnant women

|

| Campylobacter (bacterial) | Undercooked poultry, meat, or eggs; other foods that have been cross-contaminated with said poultry, meat, or eggs | Stomach cramping, diarrhea, vomiting low-grade fever. Symptoms clear up within a week. | OTC remedies (e.g. Imodium) for relief. Antibiotics for severe cases. | Arthritis, Guillain-Barre syndrome

|

| Clostridium perfringens (bacterial) | Meat, poultry, gravy, soups | Stomach cramping, diarrhea. | Drinking fluids to prevent dehydration. Antibiotics usually not needed. | Uncommon. |

| Toxoplasma gondii (parasite) | Meat, shellfish | Stomach cramping, diarrhea, swollen lymph nodes, vomiting low-grade fever. Asymptomatic cases are common. | OTC, home remedies for most cases. Antiparasitic medication give to at-risk groups (older adults, immuno-compromised individuals, pregnant women, newborns, and infants). | Eye and brain damage. Mental/physical impairments in newborns. Organ damage, cancer in HIV-positive individuals. |

| Listeria monocytogenes

|

Raw vegetables, meat, unpasteurized milk, cheese, hot dogs, deli meat

|

Stomach cramping, diarrhea, vomiting low-grade fever. Asymptomatic cases are common.

|

OTC remedies (e.g. Imodium) for relief. Antibiotics for severe cases and in pregnant women to protect the baby.

|

Listeria infection disproportionally affects older adults, immuno-compromised individuals, pregnant women, newborns, and infants. These special populations are more vulnerable to complications.

|

Preventing FBI’s

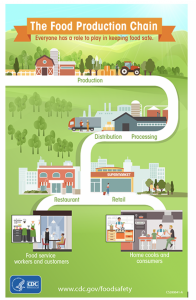

When does food get contaminated? There are several places in the chain of food production where food can become contaminated. Figure XX is an infographic made by the CDC that maps out the steps of food production. From “farm to fork”, food can be contaminated by infectious agents at numerous levels, and can become contaminated more than once in the chain of production and distribution. Table 6.1 outlines examples of how food can become contaminated at each stop in the food production chain.

Table 6.1: How food can be contaminated during food production

| Step in Food Production Chain | How Food Can Become Contaminated (all examples are pulled from CDC, 2017, https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/production-chain.html#infographic) |

| Production | Transmission of infection from hen to her eggs. Spraying produce with contaminated water |

| Processing | If contaminated water or ice is used to wash, pack, or chill fruits or vegetables, the contamination can spread to those items. During the slaughter process, germs on an animal’s hide that came from the intestines can get into the final meat product. If germs contaminate surfaces used for food processing, such as a processing line or storage bins, germs can spread to foods that touch those surfaces. |

| Distribution | If refrigerated food is left on a loading dock for long time in warm weather, it could reach temperatures that allow bacteria to grow. Fresh produce can be contaminated if it is loaded into a truck that was not cleaned after transporting animals or animal products. |

| Restaurant Preparation | If a food worker stays on the job while sick and does not wash his or her hands carefully after using the toilet, the food worker can spread germs by touching food. If a cook uses a cutting board or knife to cut raw chicken and then uses the same knife or cutting board without washing it to slice tomatoes for a salad, the tomatoes can be contaminated by germs from the chicken. Contamination can occur in a refrigerator if meat juices get on items that will be eaten raw. |

| At home | Not properly practicing the Core Four practices: Clean, Separate, Cook, and Chill. (more information is found in the section “Preventing FBIs – What consumers can do to reduce risk”. |

Public health agencies implement checks and balances at each state of food production that help to reduce the risk for contamination. For example: “CDC helps make food safer by: Working with partners to determine the major sources of foodborne illnesses and number of illnesses, investigate multi-state foodborne disease outbreaks, and implement systems to prevent illnesses and detect and stop outbreaks. Government partners include state and local health departments, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Food Safety and Inspection Service. The food industry, animal health partners, and consumers also play essential roles. Helping state and local health departments improve the tracking and investigation of foodborne illnesses and outbreaks through surveillance systems such as PulseNet; the System for Enteric Disease Response, Investigation, and Coordination (SEDRIC); and other programs. Using data to determine whether prevention measures are working and where further efforts and additional targets for prevention are needed to reduce foodborne illness. Working with other countries and international agencies to improve tracking, investigation, and prevention of foodborne infections in the United States and around the world.

Check for Understanding: Click the step in the food production chain is affected

What happens when there is an outbreak?

You probably have heard a news story about an FBI outbreak. Chipotle, for example, was in the news several times between 2015 and 2018 due to E. coli and Listeria outbreaks linked to improper food sanitation. So, how do outbreaks get traced? Click on infographic and watch this video made by the CDC to learn the public health response to investigate how FBI outbreaks are investigated “from farm to fork”.

Where can you go as a consumer to learn about FBI outbreaks? SEDRIC updates their reports of multi-state outbreaks every Wednesday. Click here to read the current outbreaks. The CDC lists outbreaks by year and by infectious agent here. Outbreaks of Vibrio and campylobacter are also published through the CDC. Local outbreak data can be retrieved from city or county health departments.

Preventing FBIs – What consumers can do to reduce risk

Practicing the same set of sanitary behaviors helps reduce the risk for all of the FBI’s discussed in Table XX. The Partnership for Food Safety Education refers to them as the Core Four practices: Clean, Separate, Cook, and Chill.

Clean: Correctly washing your hands and your food, when needed, can help prevent the spread of microorganisms that cause FBI’s. Click here to read the fact sheet from the Partnership for Food Safety Education.

Separate: Certain foods should never mingle. From the time they are placed in your grocery cart to the time they are getting prepared, keeping these foods separate is important to reduce FBI risk. Click here to read the fact sheet from the Partnership for Food Safety Education.

Cook: Cooking foods to their required minimum temperature as measured with a food thermometer is important to kill any bacteria to which certain foods can be a reservoir. It is a good idea to keep a list of all of the required cooking temperatures in a convenient place in your kitchen. Click here to read the fact sheet from the Partnership for Food Safety Education.

Chill: Just as cooking foods to their needed temperature is important, so is cooling and storing at the proper temperature. Click here to read the fact sheet from the Partnership for Food Safety Education.

Challenges in Preventing FBI’s

At the national level, the CDC works with other agencies to slow the emergence of antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria that cause FBIs. We live in a global, world, however, and countries rely on each other to source various foods. At the global level, the WHO has developed guidelines for the investigation and control of FBI’s. The WHO also recognizes this is not an easy matter due to the various challenges to global food production and distribution.

According to the WHO:

“There are many reasons for foodborne disease remaining a global public health challenge. As some diseases are controlled, others emerge as new threats. The proportions of the population who are elderly, immunosuppressed or otherwise disproportionately susceptible to severe outcomes from foodborne diseases are growing in many countries. Globalization of the food supply has led to the rapid and widespread international distribution of foods. Pathogens can be inadvertently introduced into new geographical areas, such as with the discharge of ballast water contaminated with Vibrio cholerae in the Americas in 1991. Travellers, refugees and immigrants may be exposed to unfamiliar foodborne hazards in new environments. Changes in microorganisms lead to the constant evolution of new pathogens, development of antibiotic resistance, and changes in virulence of known pathogens. In many countries, as people increasingly consume food prepared outside the home, growing numbers are potentially exposed to the risks of poor hygiene in commercial foodservice settings. All of these emerging challenges require that public health workers continue to adapt to a changing environment with improved methods to combat these threats,” (WHO, 2008, p. 5).

“Health officials don’t solve every outbreak. Sometimes outbreaks end before enough information is gathered to identify the likely source. Officials thoroughly investigate each outbreak, and they are constantly developing new ways to investigate and solve outbreaks faster, (CDC, 2016, para. 5). Twenty years ago, PulseNet was created through the CDC. PulseNet is a network of laboratories across the county that use “the DNA fingerprints of bacteria making people sick to detect thousands of local and multi-state outbreaks” (CDC, 2021, para. 1). The ultimate goal is to improve food safety for the public. Each state has at least one laboratory in the PulseNet network. Click on this link to read the PulseNet timeline since its inception in 1996.

The current technology uses whole genome sequencing, called metagenomics, to detect infectious agents faster to improve the entire investigative process of an FBI outbreak. According to Gruetzke et al (2019), “metagenomics has the potential to become a powerful tool in the field of modern food safety, since it allows the detection, identification and characterization of a broad range of pathogens in a single experiment without pre-cultivation within a couple of days,” (para 1).

Food Safety Modernization Act

The Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) passed by President Obama in 2011 was the first sweeping legislation passed to control the largely preventable outbreaks of FBI. The U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) was given agency over enacting the FSMA and enforcing food safety compliance.

The FSMA gave the FDA five new authorities:

- Prevention

- Inspection and compliance

- Response

- Imports

- Enhanced Partnership

There are seven foundational FSMA rules for the following:

- Preventive Controls for Human Food

- Preventive Controls for Animal Food

- Produce Safety

- Foreign Supplier Verification Program

- Third Party Certification

- Sanitary Transportation

- Intentional Adulteration

FSMA only applies to foods that are regulated by the FDA which accounts for 75% of the U.S. food supply and covers commercial farms, packing operations and food processing facilities. As federal oversight continues to grow in agriculture and food production, smaller groups are worried about the costly impact the new regulations will create. Recently, in December 2021, it was proposed to enhance safety requirements on agricultural water used on produce following numerous FBI outbreaks related to pre-harvest agricultural water. This proposal would require extensive water quality testing that small groups fear that they do not have the resources to meet compliance.

In 2019, the FDA launched the Food Safety Dashboard to track and evaluate the 7 FSMA rules for improvement. All proposals for requirements, reports and meetings about FSMA since its creation can be found on the FDA’s website.

recall quiz

discussion questions

- You are working as a coordinator of special programs at a local health department. As part of your role, you are responsible for managing FBI outbreaks in your community. An outbreak of listeria has just been identified. What are some actions you and your agency will take to control and eliminate this outbreak?

- You are hosting a barbecue at your home. Using the Partnership for Food Safety Education 4 core practices, explain how you would protect your guests from an FBI (give one example for each of the core 4 practices).

references

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.-a). CDC and food safety. https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/pdfs/cdc-and-food-safety.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.-b). CDC estimates of foodborne illness in the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/foodborneburden/PDFs/FACTSHEET_A_FINDINGS.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). Outbreak investigations help everyone make food safer. https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/pdfs/investigations-make-food-safer-508c.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018a, May 16). CDC in action: Foodborne outbreaks [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iIaKWNZhz74

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018b, October 2). Clostridium perfringens (C. perfringens). https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/diseases/clostridium-perfringens.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018c, December 3). People at risk: Older adults. https://www.cdc.gov/listeria/risk-groups/elderly.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019a). Norovirus. https://www.cdc.gov/norovirus/trends-outbreaks/outbreaks.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019b). Outbreaks involving campylobacter. https://www.cdc.gov/campylobacter/outbreaks/outbreaks.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019c). Selected outbreaks. https://www.cdc.gov/vibrio/outbreaks.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019d). Toxoplasmosis: Treatment. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/toxoplasmosis/treatment.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019e, May 2). PulseNet timeline. https://www.cdc.gov/pulsenet/anniversary/timeline.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021a, September 2). Salmonella and food. https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/communication/salmonella-food.html#:~:text=What%20Can%20Cause%20Salmonella%20Infection

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021b, October 1). PulseNet. https://www.cdc.gov/pulsenet/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022a, July 28). SEDRIC: System for enteric disease response, investigation, and coordination. https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/outbreaks/tools/sedric.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Ffoodsafety%2Foutbreaks%2Finvestigating-outbreaks%2Fsedric.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022b, July 28). Types of data collected in foodborne outbreak investigations. https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/outbreaks/basics/data-types-collected.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Ffoodsafety%2Foutbreaks%2Finvestigating-outbreaks%2Findex.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022c, August 10). How food gets contaminated. https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/production-chain.html#infographic

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022d, August 19). List of multistate foodborne outbreak notices. https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/outbreaks/lists/outbreaks-list.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Ffoodsafety%2Foutbreaks%2Fmultistate-outbreaks%2Foutbreaks-list.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022e, October 4). Active investigations of multistate foodborne outbreaks. https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/outbreaks/lists/active-investigations.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Ffoodsafety%2Foutbreaks%2Fmultistate-outbreaks%2Findex.html

Grützke, J., Malorny, B., & Hammerl, J. A. et al. (2019). Fishing in the soup: Pathogen detection in food safety using metabarcoding and metagenomic sequencing. Frontiers in Microbiology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01805

Healthwise Staff. (2021, July 1). Foodborne Illness: Toxoplasmosis. Myhealth.alberta.ca. https://myhealth.alberta.ca/Health/Pages/conditions.aspx?hwid=ug2077#:~:text=Severe%20toxoplasmosis%20results%20in%20damage

https://www.cdc.gov/ecoli/general/index.html. (2014, December 1). E. coli: Questions and answers. C. https://www.cdc.gov/ecoli/general/index.html

Mayo Clinic. (2021, October 1). 8 ways to protect yourself from E. coli. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/nutrition-and-healthy-eating/expert-answers/e-coli/faq-20058034#:~:text=Foods%20that%20have%20been%20linked

Mayo Clinic. (2022, February 11). Listeria infection (listeriosis): Symptoms and causes. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/listeria-infection/symptoms-causes/syc-20355269#:~:text=Raw%20vegetables%20that%20have%20been

Mayo Clinic Staff. (2017). Norovirus infection: Symptoms and causes. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/norovirus/symptoms-causes/syc-20355296

Minnesota Department of Health. (n.d.). There’s no such thing as stomach flu. https://www.health.state.mn.us/diseases/norovirus/nostomachflu.pdf

New York State Department of Health. (2022, February). Campylobacteriosis fact sheet. https://www.health.ny.gov/diseases/communicable/campylobacteriosis/fact_sheet.htm#:~:text=Eating%20undercooked%20poultry%2C%20meat%2C%20or

Partnership for Food Safety Education. (2015a). The core four practices. https://www.fightbac.org/food-safety-basics/the-core-four-practices/

Partnership for Food Safety Education. (2015b, June 17). About foodborne illness. https://www.fightbac.org/food-poisoning/about-foodborne-illness/

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2017, November 22). Prevent illness from C. perfringens. FoodSafety.gov. https://www.foodsafety.gov/blog/prevent-illness-c-perfringens

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2016). Food safety legislation key facts. • Http://Wayback.archive-It.org/7993/20170111192604/Http://Www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceRegulation/FSMA/Ucm237934.Htm.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2019). Background on the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA). https://www.fda.gov/food/food-safety-modernization-act-fsma/background-fda-food-safety-modernization-act-fsma

World Health Organization. (2008). Foodborne disease outbreaks: Guidelines for investigation and control. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43771