30 The Future of the Public Mission of Universities

Robin DeRosa

Keynote for “Making Knowledge Public,” the 2018 President’s Dream Colloquium at Simon Fraser University

I would like to begin by acknowledging the Squamish, Musqueam, Tsleil-Waututh, Katzie and Kwikwetlem peoples on whose traditional territories Simon Fraser’s three campuses stand. And back home in the United States, today is the National Day of Mourning, and I would like to express solidarity with the Wampanoag and other indigenous communities who are marking the genocide of millions of Native people, the theft of Native lands, and the ongoing assault on Native culture.

I am grateful to be here to talk with you all today. I am focusing on the future of the public missions of universities, and I want to start with a deeply inspiring story about something I am sure you will all immediately recognize as being centrally important to this topic.

Parking meters.

Parking is inspirational.

In 2008, the city of Chicago, Illinois entered into an arrangement with a private vendor to manage the city parking meters. Deals like this seem to make sense. Instead of paying out scarce taxpayer dollars to fund expensive infrastructure, our communities contract with private investors in win-win arrangements that deliver both public infrastructure and private profit.

According to the Chicago Sun Times, Chicago Parking Meters LLC is a group that includes investors from as far away as the Middle East. These private investors who have already extracted $927 million from the deal, will recoup their full investment by 2021. They will still have 62 years of cash-flow left to enjoy. In the mean time, motorists in Chicago were so peeved about the radical increase in parking meter fees that they vandalized a bunch of parking meters; the city has to reimburse the investors for every parking meter that is out of service (including those at spots in use by disabled motorists who don’t legally pay the parking fees). While motorists pay more for parking and the city absorbs the bumps, the weight of benefits increasingly skews away from the public and toward private profit. Chicago attorney Clint Krislov tried to get the parking meter deal declared illegal on grounds that you can’t legally sell the public way. He said, “[This deal has] so chopped into the revenues the city rightly needs and should have to provide services to the people of Chicago. Like retiree health care. Like extra police. And [it keeps] on getting worse.”

I like to think about parking and bridges and roads. As a scholar of early American literature, infrastructure isn’t something I was encouraged to think a lot about in my academic training. As I’ve come to work on the scholarship of teaching and learning, I’ve become more interested in what the roadways and paths that carry learning look like, and what they should look like. So I think more about infrastructure. Back to Illinois.

The Indiana Toll Road privatized, and for a decade, travelers enjoyed an efficient new roadway and reasonable fees. And then the honeymoon ended, and the concessionaire started extracting the full maintenance and operation costs by charging motorists double for tolls.

Public-private infrastructure: a win-win?

The same article that explains this drawback to privatization– the fact that investors will extract profits and this will cost the public– also explains privatization’s up side:

During President Donald Trump’s recent visit to the Middle East, Saudi Arabia committed $20 billion to a new Blackstone infrastructure fund.

In 2017, the private equity firm Blackstone announced that it was creating a massive fund that would invest in United States infrastructure. The fund’s largest backer was the government of Saudi Arabia, which agreed to kick in half of the $40 billion. This was all just over a year before journalist Jamal Khashoggi was killed at the order of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. The Trump administration has been resistant to believing reports from their own intelligence experts that the Saudi government was behind the murder of Khashoggi. The Washington Post explains that the administration “wanted to cover for their allies in the Saudi government,” but that relationship is less about political alliances than it is about a private investment deal. What seemed at one time to be an up side to privatization (a $20 billion payout to fund critically needed American infrastructure) now becomes more vexed, as our national response to a human rights crisis– one that has enormous political relevance to a country like mine whose democratic principles are being tested daily by our leadership– is tethered to how the money flows in what Trump no doubt calls “a good deal.”

I know this talk is supposed to focus on the public mission of universities, but universities are not spaces that are separate from their contexts. I hope you will indulge me as I explore some of the ways that our publics are getting tangled with private profit across a number of sectors and spheres, so we can think about what that means for the changing shape of our learning communities. I particularly want to think about public infrastructure. Not so much the public goods, but the public flows; not so much what we own in common, but how we exist and own and interact as a commons. So that’s why I started with transportation, which is such a salient metaphor for how we connect together as humans in a public network.

So let’s hit the highway and drive down to Florida. In Pinellas County on the western coast, taxpayers rejected a 1¢ sales tax to pay for expanded bus and rail. And just two hours east of Pinellas County, public transit advocates in Altamonte Springs failed to garner enough support to create a public “FlexBus” system. Instead of their publicly-funded transit initiatives, both Florida communities ended up partnering with Uber. And they’re not the only ones. In the United States, Uber has public transit agreements with San Francisco, Atlanta, Philadelphia, Dallas, Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, and more. In New York, riders can use pre-tax dollars to carpool using Uber.

The Uberization of Public Transit

There are two things that concern me here. The first is semantic, and you know as a literature scholar, I believe that our words are powerful, not only representing but also constructing the material reality around us. So I get concerned when we call Uber-based transit partnerships “public.” As Uber extracts its profits and riders are conveniently served, we may be willing to accept this deal as a win-win. But even a winning arrangement is not the same as public infrastructure, so the misleading rhetoric obscures the erosion of a public way of operating. To understand my second concern, we can look at the flash points where these new pseudo-public deals diverge from a truly public system. In Florida, for example, travelers need mobile phones in order to take advantage of the Uber-provided, publicly-subsidized rides. The city manager of Altamonte Springs went on record with this gem:

Users will make the choice that’s best for them. If they prefer to not have a smartphone that’s the life they choose to live.

77% of Americans now own smartphones. I don’t know what the percentage is Altamonte Springs, but I can pretty safely say that many people who do not have access to smartphones in Altamonte have not intentionally “unplugged” as a “lifestyle choice,” and also that many people– especially young people, elderly people, and poor people– who do not own smartphones especially need access to public transportation. In 2016, nearly 9% of US households did not own a car. It’s not hard to imagine the Venn diagram between smartphone ownership and car ownership. And this is where Uber and public buses or rail diverge. While Uber’s model caters to the majority, a public system ideally attends as well to the vulnerable margins. While Ubers don’t all have the capacity to pick up a passenger who uses a wheelchair, all city buses and trains are equipped to accommodate disabled passengers. At its best, a public is shaped by its inclusivity, and access is a core tenet of its infrastructure. The Uberized version, however, nails the robust market even as it occludes any public needs that erode profit. So I’m worried that our public infrastructures are starting to conform to markets in ways that muddy our public missions, and I am worried that this conformity is ultimately going to rob us of the ability to recognize what a public infrastructure would look like.

Public infrastructure is certainly changing shape. North American postal services, both in Canada and in the U.S., are a good illustration of this. On the one hand, far fewer letters are being sent, which erodes the market for one of the core services offered– as well as one key source of revenues. On the other hand, thanks in particular to Amazon, a booming online shopping industry means that more and more parcels are traveling through the post every day.

Amazon: Changing Markets, Changing Metaphors

In the parcel delivery service, however, Canada Post has many competitors, including UPS, Fedex, Canpar, Dynamex, plus Purolator, which– interestingly–Canada Post owns. One Canadian economics reporter argued that it’s time for Canada Post to privatize because “delivering clothes, books and electronics for Amazon hardly qualifies as an essential public service.” It’s interesting to see the existence of a public service like postal delivery being so directly tied private commerce, but Amazon is interesting in another way as well. Amazon isn’t just an online retailer. It’s infrastructure. Every time you “log in with Amazon” or “check out with Amazon,” every time you research your purchases and decisions and surf the algorithms tied across your linked platforms, Amazon is increasingly providing and commodifying the pathways we use to interact with our world and each other.

Amazon isn’t stuff, it’s systems

I think we need to spend more time thinking not about what products are being sold to us, but how ourways of being are slowly– maybe rapidly, actually– becoming points of profit for investors who aren’t invested in, well, us.

Transportation, postal delivery, commerce. This is the infrastructure underneath daily living. In addition to how we travel, mail, and spend, there’s also how we communicate. There is possibly no infrastructure more crucial to a community than its communication systems; sometimes it may even seem that community is communication. Both come from the Latin communicare, “to share.” But these systems are privatizing as well. In 1990, the Alberta government began the process of privatizing Alberta Government Telephones. In 1991, the province sold its remaining ownership interest in AGT for $870 million.

Community is Communication

The win-win logic is again obvious, as ailing infrastructure would mean radical tax hikes if the public were to fund the up-front costs of improving technical structures that need to be kept current. And maybe it’s hard to understand how such a sweeping privatization changes the shape of our communications and therefore of our communities. So let’s look at one smaller example of how the privatization of communication has affected real people and their ability to cultivate their human connections.

Video visitation is when visitors can communicate with incarcerated prisoners over video feeds. Often video visitation happens when both the prisoner and the visitor are on site in the same building, but separated by many rooms and barriers. While video visitation has been around for a long time, it was usually clunky and sporadically located. Over the past decade, however, facilities have outsourced the systems to corporations, often as part of a package that includes phone services.

Video Visitation (Photo via Convict Soap Box)

As of 2014, according to a report by the nonprofit Prison Policy Initiative, over 500 jails and prisons in 43 states in the U.S. had adopted video visitation. In many cases, such as at one prison in Kansas, contracts with these private companies (here, Securus) require the total elimination of all face-to-face contact between prisoners and guests in order to make the video visitation– which carries a fee for visitors– more attractive. Sometimes local counties or governments get a kickback from these revenues: “10% of revenues commission to the county, but only if the number of paid video visits reached at least 8,000 for that month. If Securus grossed $2.6 million or more, the county’s percentage rose to 20%.”

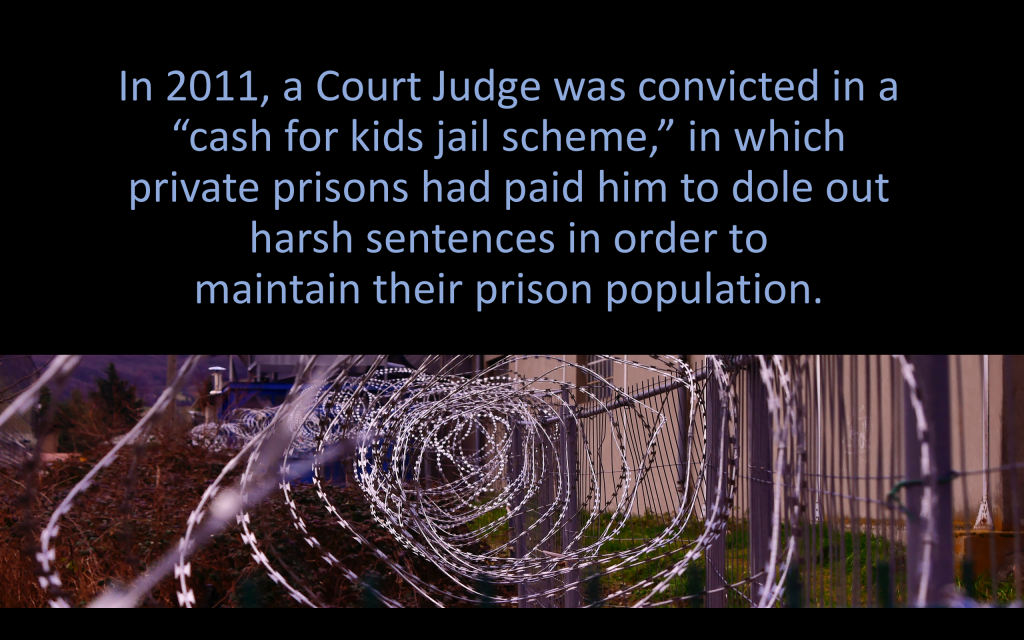

The privatization of prison communication is part of a larger, more familiar prison privatization narrative. In 2018, 8.4% of prisoners in the United States were housed in private prisons. GEO Group, one of the two largest prison operators, was one of the few publicly traded companies to openly donate large sums to the Trump effort (GEO Group also built the New Brunswick Miramichi Youth Detention Center under contract with the provincial Department of Public Safety, then had its contract ended in the 1990s after public protests). While there are a numerous reasons we might be concerned about the privatization of prisons, one obvious example is the 2011 case of a U.S. judge who was convicted in a “cash for kids jail scheme“: private prisons had paid him to dole out harsh sentences in order to maintain their prison population.

The privatization of our communication channels and the privatization of our prisons are related phenomena that subjugate both humanity and the public good to profit. In most cases, this happens not because the public wants to erode its communities, but because the sales pitch offered by private industry is seductive, and it delivers. When roads crumble, private industry can repair them quickly. When you’re stranded in the rain, private industry can get pick you up. When you need to make a call or house a prisoner, private industry can build a shiny box that serves its purpose. But the dark side is deeply ironic. The road is smooth, but the tolls are high.

Michigan law allows any private property owner to withdraw water from the aquifer under their property. One of Nestle’s key bottling plants is in Michigan, just 120 miles from Flint, which suffered a colossal drinking water pollution crisis in 2014. Many residents in Flint are still drinking bottled water (though the schools have been retrofitted with water filtration systems courtesy of a private donation from billionaire submarine failure Elon Musk). And what heartbreaking irony is it that much of that bottled water has been extracted from the public aquifer just down the road, packaged by Nestle, and then sold back to the public at outrageous markup? For this privilege, Nestle pays Michigan a $200 a year paperwork fee, and nothing at all for the water.

Photo of @LittleMissFlint

The government tells Flint residents that the tap water is safe to drink, but many residents don’t believe it because that’s been said too many times when it wasn’t true. The water issue in Flint is about aging public infrastructure: lead pipes that caused the contamination and water treatment that didn’t correct the problem. It’s about environmental racism and which problems get attended to by those with the power and money to fix them. And it’s about public trust, since the initial foul water scandal is only one aspect of ongoing betrayals in Flint. When we see public breakdowns like Flint, and the clean Nestle water ready to ship out, we might ask where we draw the lines between the products we want and the services we need in order to live a human life? Is water public infrastructure? Is air? Is education?

So I know it took a while to come around to it, but when I turn to a conversation about knowledge and education, I want to see it as part of a larger conversation about how our publics are privatizing. Because I think when we see our own work in higher education as part of a larger ecosystem, there is both more urgency and more hope about how our own interventions in our micro contexts could have larger impact. I’ll start the conversation about education in New Orleans, Louisiana. After Hurricane Katrina in 2005, public schools in New Orleans were decimated. To rebuild them must have seemed like an overwhelming task. The hurricane coincided with the rising charter school movement in the United States, and when New Orleans needed to rebuild its public schools, it was charters– and their complex public-in-name-private-in-operation character– that emerged as the preferred model:

Hurricane Katrina (Photo by Ethan Miller/Getty Images)

The schools were rebuilt under the charter model, but big changes were in store. Some of these were more particularly insidious. Of the 4,300 teachers dismissed after Katrina, 71% percent were Black. Because charter schools are often governed by free market principles, a focus on equity and social justice can be seen as an impediment to success. Jitu Brown, of Journey4Justice Alliance, a coalition of groups from Black and Brown communities impacted by charter schools, puts it this way:

It’s the colonizing of our communities, where we have people running the quality-of-life institutions in our communities through the way they see us, through their lens… If charters were so great, white folks would have them, but they don’t get charters. They get magnet schools and well-funded neighborhood schools.

And the research bears out the idea that privatization has devastating effects on vulnerable populations. In 2018, the United Nations released a report on extreme poverty and human rights:

privatization often involves the systematic elimination of human rights protections and further marginalization of the interests of low-income earners and those living in poverty. Existing human rights accountability mechanisms are clearly inadequate for dealing with the challenges presented by large-scale and widespread privatization. Human rights proponents need to fundamentally reconsider their approach.

…further marginalization of those living in poverty…

The charter issue illuminates one of the more challenging questions about public education: what is a public school? Governed by private organizations, charters still call themselves public. But, as education professor David Labaree notes, don’t some “private schools…enroll students using public vouchers or tax credits, [and some] public schools…use exams to restrict access? For that matter, don’t private schools often serve public interests, and don’t public schools often promote students’ private interests?” How much of the definition of a public institution is based on its funding sources? And how much is based on its mission?

In 2005, scholars and analysts in the United States and Canada were becoming increasingly concerned about the privatization of education, especially higher education.

Prognosticating Privatization

University of Illinois president Stanley Ikenberry rejected “privatization” as an accurate term (in 2005) to describe the current conditions for higher ed in the U.S., but he wondered if the term would one day be appropriate. That same year, Canadian sociologist Claire Polster warned of five kinds of privatization that were beginning to shape Canada’s colleges and universities:

- increasing reliance on tuition

- adoption of business values and practices

- research for hire

- rise of corporate-leaning advisory bodies

- innovation centers tied to intellectual property aimed at private profit

Just to spend a moment on the first kind of privatization there, Polster noted that between 1990-91 and 2000-2001, tuition fees in Canada rose by 126%, while average student debts rose from about $8,700 to $25,000. This was because students were paying a far larger share of the costs of postsecondary education, from an average of 17% of operating costs in 1992 to 28% of operating costs in 2002. Depending on the province in terms of severity, we can see that the rising personal tuition end debt burdens have continued to plague Canadian students and their families since 2005. And of course, in the United States, the tuition and debt burdens have become front page news, where outstanding student debt reached $1.5 trillion in the first quarter of 2018. My public university in New Hampshire is about 9% funded by the government; the rest is paid for by students through tuition.

In terms of making visible the move from public to private funding, there’s no better visible example of the shift than GoFundMe. In the United States, in the last 3 years, more than 130,000 people have raised $60 million to pay for their college tuition and related expenses. To take Ohio as an example, public colleges had the most GoFundMe requests:

- 527 from Ohio University

- 409 from Kent State

- 298 from Ohio State

- 286 from University of Akron

- 143 from Cleveland State

In 2017, the Thurgood Marshall College Fund announced a formal partnership with GoFundMe to raise money in support of students attending the nation’s forty-seven public historically black colleges. And a senior at a Baltimore, Maryland public high school launched a GoFundMe campaign and raised more than $80,000 to bring heat to her freezing school buildings. Students are increasingly carrying the burden for covering our school’s operating costs.

While tuition burdens are the most deeply-felt repercussion of privatization from a student standpoint, those of us who work in education see the effects of the shift from public infrastructure to private outsourcing across diverse sectors of our daily work lives. In higher education, our administrators play a dangerous game of mourning the decline of public support while resignedly accepting the new corporate model that reigns supreme even in our public colleges and universities. “We must change our perspective of being a pure public university, one that is supported mostly by the state, to a university that is privatized,” said Bob Davies, Former President of Murray State University, “Yes, we are a public university, yes we hold public university values and ideas, but we are becoming privatized.”

Before we talk about the effects on teaching and learning and knowledge, let’s pause to look at some of the auxiliary services that are increasingly being outsourced to private companies.

“Privatizing health services was new, but the handwriting was on the wall.”

Radford University is one of many, many institutions outsourcing its health care to a private company. We can see the diction that describes the change pointing towards a customer-service model, where TVs and skateboard racks become part of a new vision of students as consumers, who exercise choice in their college enrollments and therefore need to be wooed by the lazy river model of even basic health services. And colleges and universities feel stuck, unable to upgrade facilities when their budgets are constrained by legislatively-imposed austerity. A similar thing happens in dining, where the diction of local foods and community tables is co-opted by large national and multi-national corporations who now provide college dining services. This example is from the University of Kentucky, who contracted out its services; their new $32 million dining building is part of a 15-year, nearly $250 million partnership between the university and Aramark, a global leader in food services:

Local foods or multinational corporation?

Administrators and faculty often see outsourcing as a welcome way to relieve budgets and burdens. In 2012, private investors paid $483 million to Ohio State University for a lease to operate university parking; an accounting professor emphasized the benefits of the agreement:

Our core strength as a university is not running parking facilities. So we should focus on what we’re really good at and hire others to do what they’re really good at.

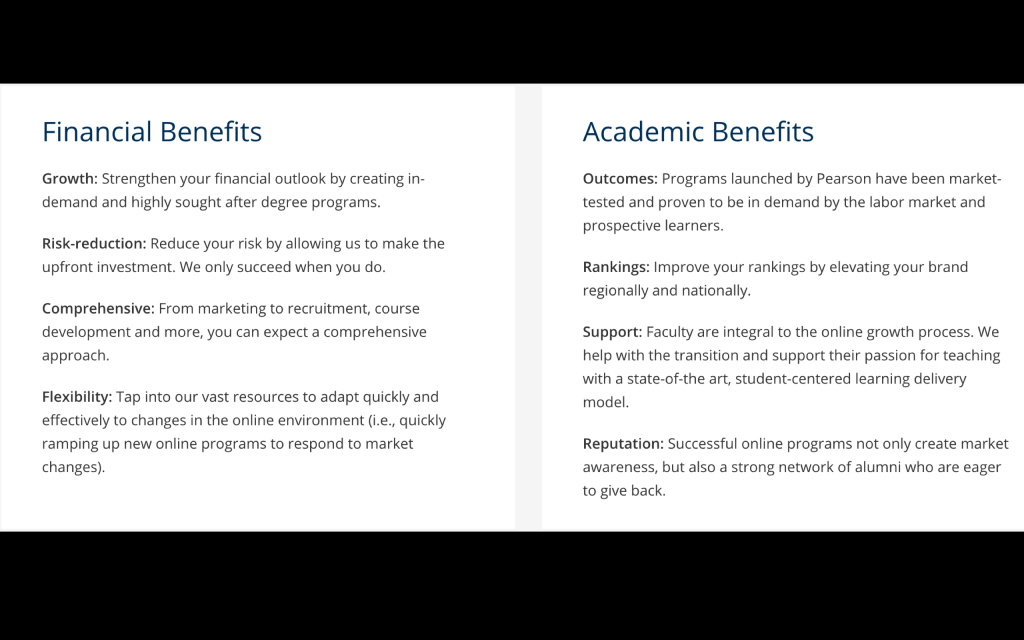

This would suggest that the slip to outsource is only in those domains that are outside of our academic missions. But this is far from true. Online Program Management (OPM) “providers” or “enablers” help to run online programs for colleges and universities. This can include everything from providing platform infrastructure to creating courses and training faculty to teach them. As far back as 2015, the OPM market value was estimated in the United States at $1.1 billion. In 2017, over 70% of the institutions that provided a response to a Century Foundation’s survey request—84 out of 117—contracted with at least one for-profit OPM to facilitate their online programming. Here’s what Pearson advertises as the benefits of contracting with them for OPM:

…those academic benefits are still pretty market-based…

The fact that OPM can put profit-driven corporations in key positions of control with respect to academic content and pedagogy in concerning, but equally as concerning is how unaware students and their families are of how this all works. Michigan State University provides an example of how OPMs operate behind the scenes. The landing page for the University’s online executive development programs features the University’s logo and a picture from inside the school’s Broad College of Business. ‘Lead Like a Spartan,’ reads a banner on the program’s website. Perusing the information available to potential students, there is no indication that an external contractor provides recruitment and marketing services, as well as course production and instructional design for many of the programs rather than the university itself or that, for each dollar these programs bring in as revenue, more than half goes to that contractor. (Mattes)

What students don’t know about who runs their online curriculum

Louisiana State University’s agreement with Academic Partnerships goes so far as to explicitly requestthat marketing materials created by the OPM blend in with LSU’s regular branding; students would not have any reason to assume that the OPM content and delivery was not entirely managed within the university itself.

OPM includes the wrap-around advertising apparatus to draw students into the programs, since so many of our online investments are driven by a frenzied belief in enrollment-based ROI. But this ends up making the data generated by students’ interactions with the OPM platforms and interfaces extremely valuable to those companies. And the contracts that OPM corporations design often include clauses that allow them to extract that data to use to enrich their own profits. 2U paid the University of California-Berkeley $4.2 million in 2014 for the permission to ask applicants, including those who were denied entry into the Berkeley program, if they would like to learn more about another, similar program offered by 2U and Southern Methodist University (Mattes). And here’s a clause from a contract between Bisk and the University of Vermont:

The University of Vermont (UVM) agrees that Bisk shall have the right to market and advertise UVM programs together with other university programs through and with the University Alliance, a Bisk brand, and therefore UVM understands and agrees that Programs students and prospects may be provided with information on other University Alliance offerings. (Mattes)

2U, Bisk, and Your Public University

It’s hard to see this all as anything other than a profit-driven attempt to commodify education, consumerize students, monetize data, manipulate algorithms and shift teaching and learning into an enterprise.

The backdrop for the rise of OPM is a fully corporatizing university space. As public funding retracts and auxiliary outsourcing expands, universities play a dangerous game with private industry. Joshua Hunt’s recent book, The University of Nike, tells the disturbing story of how declines in state support for higher education in Oregon in the mid-to-late 1990’s provided the perfect pressurized environment for the flourishing of a robust donor relationship between the University of Oregon and alum and chief Nike executive Phil Knight. The book illustrates the disturbingly active role that Knight and Nike played in university operations. Within a few years of Knight’s first $27 million gift (to fund a university library in 1994), “Nike was calling the shots” on campus, with “Nike employees…consulting on various projects alongside university employees.”

“Nike was now calling the shots”

For those of us who work at universities not lucky enough to be shadow-controlled by Phil Knight, we might experience this corporate lean in a way that seems to be more connected to regional community needs. “Workforce partnerships,” where local industries help fund facilities and curriculum development in high-need labor markets, are designed to meet needs for both the markets and for students who will be graduating into them and who hope to be employed (not incidentally, so they can pay off their student loans). It’s another of the win-wins. But what is the long game here, from a public good perspective? If an institution takes on– for no compensation– the training of entry-level employees for an industry, what reason is there for that industry to retain or promote those employees as the field develops and changes, since they have a neverending pipeline of newly trained, less expensive young employees at the ready?

Sociologist Tressie McMillan Cottom tackles this in her groundbreaking book, Lower Ed. McMillan Cottom argues that we now think of college as an individual good, rather than a collective good that benefits society, which helps explain the credentializing craze that encourages learners to gird themselves against a rough labor market by accumulating certificates and degrees. She links the recent rise of for-profit colleges to our growing national aversion to public responses to labor market crises. When we have “skills gaps,” under- or unemployment, demographic shifts that affect industry, outsourcing and automation trends– when we have any challenge that confronts our students upon graduation, we solve these problems by asking industry what it needs to feel better. But what industry needs and what our students and communities need may not always be the same thing.

We now think of a college education as an individual rather than collective good.

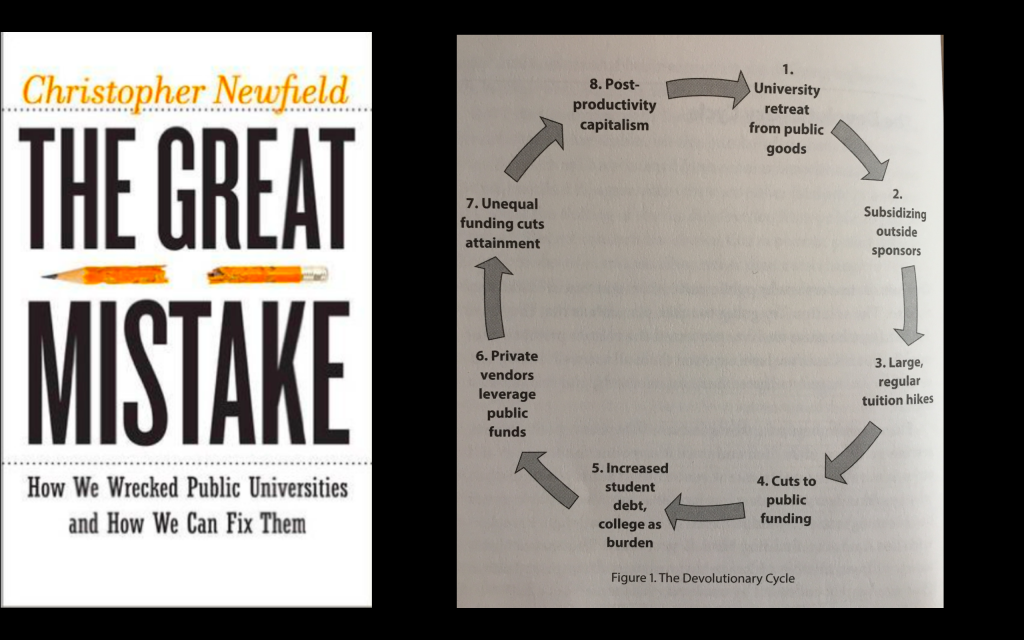

I think one of the best books for understand what happens when we place our faith in private markets to pull public higher education out of its crisis is Christopher Newfield’s The Great Mistake: How We Wrecked Public Universities and How We Can Fix Them. Newfield argues that private sector “reforms” are not the cure for the college cost disease– they are the college cost disease; they set up a devolutionary cycle that shifts resources away from education while raising rather than containing costs.

The Devolutionary Cycle

We can see so many of the privatizing trends I’ve talked about represented in this cycle, from outsourcing to tuition hikes to the shift to private OPM vendors. What’s stunning about Newfield’s work, though, is how he sifts through the fallout in specific public colleges and universities to trace the negative impact that this privatizing turn has had on bottom-line revenues. In other words, regardless of what you think about the effect on teaching and learning, the other dirty little fact is that privatizing doesn’t even fix the myopic problems it seeks to solve.

Newfield wants those of us inside public higher education to reclaim our public missions. In the final part of this talk, I want to articulate what that might look like. What does it mean to resist the trends as I’ve outlined them here, and instead focus our colleges and universities on teaching, learning, and research for the public good?

We started by talking about the Uberization of public transportation, but I also want to suggest that private industry does not corner the market on innovation. Take RideAustin, for example. When it first rejected Uber’s request to operate within its city limits, Austin knew there were transportation needs that its current public infrastructure was not meeting. RideAustin is a public version of an Uber-type system, but it has critical differences. Part of its stated mission is “doing right by drivers, ensuring a fair wage, doing right by the community.” And RideAustin leadership states that they “want to make transportation more accessible for everyone in the Austin area.” RideAustin donates to local charities as part of its structural operations, offers free rides for doctor visits for those in needs, abides by city regulations, and (in stark contrast to Uber) makes its operational data public.

Public transportation “innovates”

RideAustin is no panacea for anything, but it is a public response to a need, a response that returns its revenues back into the public ecosystem, and that centers access ahead of profit. I wonder how public higher education can resist Uberization, and innovate around principles that truly sustain our public ecosystems for learning and research.

I don’t study any of this stuff for a living. I teach for a living. Through my teaching, I have come to care deeply about making education more accessible for more of my current and potential future students. When former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg, the 11th richest person in the world, announced last week that he was giving $1.8 billion to Johns Hopkins University, I shuddered, wondering how someone who’d once governed the city could imagine that one of the richest private universities in the world– with an endowment already topping $3 billion– would be a better choice to receive this gift than the City University of New York, which enrolls a quarter million learners and hasone of the most diverse student bodies in the United States. And then, after that shudder, I shudderedagain to think that the best option I could imagine for CUNY was that a rich philanthropist would decide it was politically expedient for him to donate money to support the school.

If you think I’m about to tell you how we generate $1.8 billion through public sources without alienating our tax base, sorry. But I am going to suggest that we need to start building evidence and a vocabulary for the value of our public work. It’s ridiculous to assume that it’s not a case that we can effectively make.Even in purely economic terms, there is substantial evidence that when taxpayers invest in public higher education, the financial rewards that are returned directly to them far outweigh their costs.

Philip Trostel at the University of Maine released fantastic research funded by the Lumina Foundationin 2015. He quantified the rate of return on taxpayer investment in college students at 10.3%, and the rate of return to state and local governments at 3.1%. The fact that we think higher education is expensive for taxpayers and municipalities has nothing to do with math and everything to do with political rhetoric that protects the richest members of society– like Bloomberg– from paying a fair share. The spin is carefully orchestrated by a small percentage of wealthy folks protecting their interests, and we need to unspin it.

Interestingly, Trostel’s report is titled “It’s Not Just the Money.” He details in its pages how we also undervalue benefits that go beyond the simple math of earnings. We all benefit from public higher education in private and public ways, in ways tied to markets and ways that aren’t directly tied to markets. For example, the College Earnings Premium (CEP) is well documented. Trostel calculates that individual college graduates earn an average of 114% more than they would if they did not have a college degree. But focusing only on those private market benefits obscures other equally amazing benefits.

Benefits Beyond CEP

Don’t tell me these are not persuasive. Live seven years longer!! Why don’t we talk about these? Why do we run so quickly to industry partnerships and private donors when the public power of education is so clearly valuable?

I’d like to argue that every single faculty and staff member, beyond just our leadership, needs to become versed in value of what we do. And then we need to tie the mission of public access and public investment to the actual work that we do in designing our courses and programs. This is the main reason I have come to open.

Ecosystems, Not Solutions (image by Abby Clobridge)

As I conceive of it, open is an ecosystem, made up of many related aspects. I could talk about all of them here, but really my focus is on open education, particularly open access, open educational resources, and open pedagogy.

Open Access to Research

Public colleges and universities should have public funding to conduct research, and the results of that research should not be paywalled so that the public has to pay twice. Our libraries need to enter into consortia to flip to open access journals and resist the publishing conglomerates that bundle journals into exorbitantly priced units that students pay for through their tuition dollars. Faculty need to pass open access resolutions and support the publication of open access research in promotion and tenure processes, and we need to focus on peer review systems that offer strong quality control measures in our OA publications. If every public college and university– all of our librarians, all of our faculty, all of our administrators– committed to this and worked on it for a year, we’d simply do it. Open Access matters because the profit motive is problematic for the growth of knowledge. Take a recent kerfluffle with the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, where an article critical about how some doctors were being recruited by companies to promote medical practices that enriched those companies was taken off the journal’s website eight days after publication due to pressure from private industry. As a skin cancer patient, believe me when I say I don’t want anyone with a profit motive driving the publication mechanisms of dermatological research. And a taxpayer who funds autism research should have the opportunity to read an article about new treatments that could help her autistic son, even if she has no institutional access to a library database. Open Access isn’t just weaning off Elsevier. It’s a broader commitment to the integrity of our research, the free flow of ideas, and the belief that our work can and should matter in the world outside the academy.

Open Educational Resources

We should convert all textbooks, all materials made expressly for teaching, to open educational resources. We should fund their creation robustly, and fund their updating. We should partner across institutions to do it. If all faculty committed to adopting OER and creating more to fill in the gaps, and all administrators committed to directing funds to this work, we could do this in a year. We could just do it. OER matters not because textbooks matter. OER matters because it highlights an example of how something central to our public missions, the transfer of our foundational disciplinary knowledge from one generation of scholars to the next, has been co-opted by private profit. And OER is not a solution, but a systemic shift from private to public architecture in how we deliver learning.

Open Pedagogy

Open pedagogy is way of thinking about teaching and learning that foregrounds access, commons-oriented approaches to sharing knowledge, and connections inside of and between communities. On the ground in my courses, this can look lots of ways. It’s in my Open Anthology of Earlier American Literature, co-written with my students. It’s in my students’ ePorts, where they contribute their research and ideas back into the worldwide web instead of just being perpetual consumers of knowledge. It’s in openly licensing the materials I create for teaching, and in calling in collaborators instead of calling out competitors across sister institutions.

But whether it’s about how we research and publish, how we transmit information, how we teach and learn, open is most centrally about designing infrastructure from the perspective of our publics. This is not about openly licensing any one particular artifact. This is not about saving students $100 on a textbook here or there. This is about taking a stand for an ecosystem powered by infrastructure that actively strengthens the public good. I know that the “public good” is not easy to qualify; and hell, it’s even harder to quantify. But we know what privatization looks like, and we know that gated communities sequester and starve knowledge growth, and we know what public returns look like.

My plea today is that we build an international commitment to the value and language of public. That we create open ecosystems in government, data, science, research, education, and software that are contextual, tied to community need, and reflective of the diversity of the real people who depend on our universities to do good work and improve the condition of the world. Don’t tell me we’ve already lost. We haven’t given this a real go yet. I want to hear this from every level of our colleges. Faculty in physics and ceramics and machining and occupational therapy. Writing center tutors. Facilities and maintenance staff, deans and provosts, student activities planners, administrative assistants and instructional designers and technologists. Presidents. All of us, we all have to look at the area that we work in and ask:

what is slipping towards the private here? what would public infrastructure look like to do this work? what language do I need to describe a public vision for this future? what public value does this work deliver? how does this work strengthen a larger public good? how can public resources be sewn and grown to sustain a lasting and verdant ecosystem for education?

What value does public space have?

Why do we need public spaces for learning?

What does it look like to create and sustain a public space?

Don’t tell me it can’t be done. Look around. It’s us. Why not?

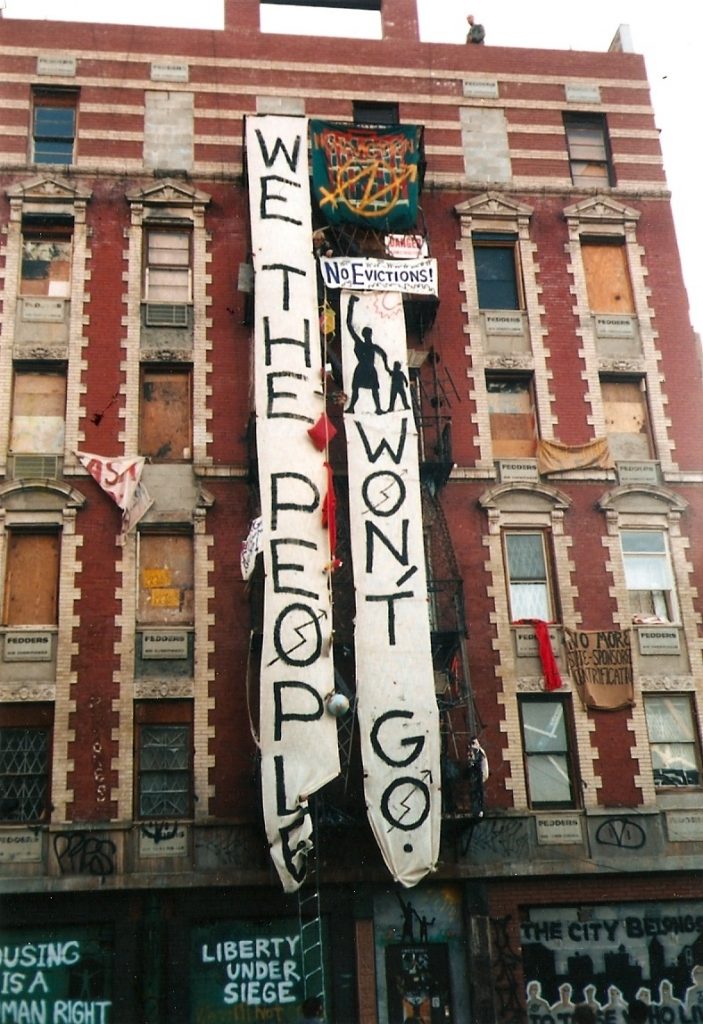

Squatters defy eviction for 2 decades, & flip building to public housing. (Photo from Amy Starecheski via 99percentinvisible.org)

Works Cited

This Works Cited was generated by Zotero. It’s imperfect, and I’ll work on trying to clean it up over the next few days.

“Academic Partnerships.” Academic Partnerships Online, http://www.academicpartnerships.com/. Accessed 15 Nov. 2018.

Alexander, Brian. “When Prisoners Are a ‘Revenue Opportunity.’” The Atlantic, 10 Aug. 2017, https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2017/08/remote-video-visitation/535095/.

Berman, Jillian. “Student Debt Just Hit $1.5 Trillion.” MarketWatch, https://www.marketwatch.com/story/student-debt-just-hit-15-trillion-2018-05-08. Accessed 18 Nov. 2018.

Bloomberg, Michael R. “Opinion | Michael Bloomberg: Why I’m Giving $1.8 Billion for College Financial Aid.” The New York Times, 19 Nov. 2018. NYTimes.com, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/18/opinion/bloomberg-college-donation-financial-aid.html.

Canada’s Road to Postal Privatization. https://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2011/12/06/how-to-help-the-post-office/canadas-road-to-postal-privatization. Accessed 25 Oct. 2018.

Champions Kitchen – University of Kentucky. https://uky.campusdish.com/LocationsAndMenus/ChampionsKitchen. Accessed 15 Nov. 2018.

Cohen, Donald. Is Your Local Public Library Run by Wall Street? – In the Public Interest. https://www.inthepublicinterest.org/is-your-local-public-library-run-by-wall-street/. Accessed 25 Oct. 2018.

Cottom, Tressie McMillan. Lower Ed: The Troubling Rise of For-Profit Colleges in the New Economy. The New Press, 2018.

Dillon, Sam. “At Public Universities, Warnings of Privatization.” The New York Times, 16 Oct. 2005. NYTimes.com, https://www.nytimes.com/2005/10/16/education/at-public-universities-warnings-of-privatization.html.

“Fighting the Privatization Wave.” ACADEME BLOG, 22 Oct. 2018, https://academeblog.org/2018/10/22/fighting-the-privatization-wave/.

Foran, Max. Calgary, Canada’s Frontier Metropolis : An Illustrated History. Windsor Publications, 1982, http://www.ourfutureourpast.ca/loc_hist/page.aspx?id=3610564.

French, Sally. “All the Companies in Jeff Bezos’s Empire, in One (Large) Chart.” MarketWatch, https://www.marketwatch.com/story/its-not-just-amazon-and-whole-foods-heres-jeff-bezos-enormous-empire-in-one-chart-2017-06-21. Accessed 17 Nov. 2018.

“Go Fund Me.” Trinity Western University, 6 Dec. 2017, https://www.twu.ca/financial-aid/go-fund-me.

—. Trinity Western University, 6 Dec. 2017, https://www.twu.ca/financial-aid/go-fund-me.

Goldenstein, Taylor. “Pilot Program to Offer Low-Income Patients Free Trips to Doctor.” Austin American, https://www.statesman.com/NEWS/20170706/Pilot-program-to-offer-low-income-patients-free-trips-to-doctor. Accessed 28 Oct. 2018.

Hannigan, John. Fantasy City: Pleasure and Profit in the Postmodern Metropolis. Routledge, 1998. WorldCat Discovery Service, http://catdir.loc.gov/catdir/enhancements/fy0649/98023774-d.html.

HESA_SPEC_2018_final.Pdf. http://higheredstrategy.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/HESA_SPEC_2018_final.pdf. Accessed 16 Nov. 2018.

How a Garden for the Poor Became a Playground for the Rich – The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/10/18/nyregion/new-york-city-inequality-gentrification.html. Accessed 25 Oct. 2018.

“How the Large-Scale Privatization of New Orleans’ Schools Upholds Inequality.” Truthout, https://truthout.org/articles/how-the-large-scale-privatization-of-new-orleans-schools-upholds-inequality/. Accessed 25 Oct. 2018.

“Trump Won’t Believe His Own Intelligence Community — Again.” Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2018/11/15/trump-administration-is-trying-hard-not-blame-saudi-crown-prince-khashoggis-death/. Accessed 17 Nov. 2018.

Hunt, Joshua. “The Secret Betrayal That Sealed Nike’s Special Influence Over the University of Oregon.” Pacific Standard, https://psmag.com/education/the-secret-betrayal-that-sealed-nikes-special-influence-over-the-university-of-oregon. Accessed 16 Nov. 2018.

“Ins and Outs of Privatization.” American School & University, 1 Sept. 1998, https://www.asumag.com/outsourcingcontract-services/ins-and-outs-privatization.

Is It Time to Get Rid of Canada Post? – National | Globalnews.Ca. 18 Oct. 2018, https://globalnews.ca/news/4567926/privatization-canada-post/.

It’s Time for Ottawa to Think about Privatizing Canada Post’s Booming Parcel Delivery Business. The Globe and Mail, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/commentary/article-its-time-for-ottawa-to-think-about-privatizing-canada-posts-booming/. Accessed 15 Nov. 2018.

Labaree, David F. “Public Schools for Private Gain: The Declining American Commitment to Serving the Public Good.” Kappanonline.Org, 22 Oct. 2018, http://www.kappanonline.org/labaree-public-schools-private-gain-decline-american-commitment-public-good/.

Labott, Elise, Veronica Stracqualursi and Jeremy Herb. “CIA Concludes Saudi Crown Prince Ordered Journalist’s Death, Sources Say.” CNN, https://www.cnn.com/2018/11/16/politics/cia-assessment-khashoggi-assassination-saudi-arabia/index.html. Accessed 17 Nov. 2018.

Markgraf, Matt. Murray State President: "We Are Becoming Privatized" http://www.wkms.org/post/murray-state-president-we-are-becoming-privatized. Accessed 25 Oct. 2018.

Mohler, Jeremy. Why Public Space Is so Valuable – In the Public Interest. https://www.inthepublicinterest.org/why-public-space-is-valuable/. Accessed 25 Oct. 2018.

“Nestlé Plans Dramatic Expansion of Water Privatization in Michigan, Just 120 Miles From Flint.” EcoWatch, 2 Nov. 2016, https://www.ecowatch.com/nestle-bottled-water-flint-2075968508.html.

Newfield, Christopher. The Great Mistake: How We Wrecked Public Universities and How We Can Fix Them.Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018.

Demographics of Mobile Device Ownership and Adoption in the United States. http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/mobile/. Accessed 17 Nov. 2018.

DeRosa, Robin. OER Is Catalyst for National Conversation about Public Higher Education | Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/views/2017/11/01/oer-catalyst-national-conversation-about-public-higher-education. Accessed 18 Nov. 2018.

Online Program Management. https://www.pearson.com/us/higher-education/products-services-institutions/online-program-management.html. Accessed 15 Nov. 2018.

Online Program Management Providers, Now a Billion-Dollar Industry, Look Ahead. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2015/09/11/online-program-management-providers-now-billion-dollar-industry-look-ahead. Accessed 18 Nov. 2018.

“Parking Meter Deal Keeps Getting Worse for City as Meter Revenues Rise.” Chicago Sun-Times, https://chicago.suntimes.com/politics/parking-meter-deal-keeps-getting-worse-for-city-as-meter-revenues-rise/. Accessed 17 Nov. 2018.

Privatizing Canada’s Public Universities. https://canadiandimension.com/articles/view/privatizing-canadas-public-universities-claire-polster. Accessed 25 Oct. 2018.

Schiller, Ben, and Ben Schiller. “Could London Set Up A Nonprofit, Cooperative Alternative To Uber?” Fast Company, 2 Oct. 2017, https://www.fastcompany.com/40473251/could-london-set-up-a-nonprofit-alternative-to-uber.

Schofer, Joseph L. “Pay Toll Ahead; Privatizing Infrastructure Comes with a Trade-Off.” Chicagotribune.Com, https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/opinion/commentary/ct-infrastructure-privatize-tolls-fees-costs-perspec-0613-md-20170612-story.html. Accessed 25 Oct. 2018.

Sernovitz, Gary. What New Orleans Tells Us About the Perils of Putting Schools on the Free Market. July 2018. www.newyorker.com, https://www.newyorker.com/business/currency/what-new-orleans-tells-us-about-the-perils-of-putting-schools-on-the-free-market.

“Squatters of the Lower East Side.” 99% Invisible, https://99percentinvisible.org/episode/squatters-lower-east-side/. Accessed 25 Oct. 2018.

“Flint Schools Receive Water Stations, Filtration Systems from Billionaire Elon Musk.” https://www.abc12.com/content/news/Flint-schools-receive-water-stations-filtration-systems-from-billionaire-Elon-Musk-495276151.html. Accessed 18 Nov. 2018.

Picchi, Aimee et al. One Winner under Trump: The Private Prison Industry. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/one-winner-under-trump-the-private-prison-industry/. Accessed 26 Oct. 2018.

“The Private Side of Public Higher Education.” The Century Foundation, 7 Aug. 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/private-side-public-higher-education/.

“The Problem With Privatizing Prisons.” JSTOR Daily, 15 May 2017, https://daily.jstor.org/the-problem-with-privatizing-prisons/.

“Thurgood Marshall College Fund Announces GoFundMe Partnership For HBCU Students.” Black Enterprise, 7 Nov. 2017, https://www.blackenterprise.com/thurgood-marshall-college-fund-announces-gofundme-partnership/.

Trostel, Philip, and Margaret Chase Smith Policy. IT’S NOT JUST THE MONEY. p. 73.

UK Breaks Ground on New Dining, Student Support Facility – Lane Report | Kentucky Business & Economic News. https://www.lanereport.com/38228/2014/09/uk-breaks-ground-on-new-dining-student-support-facility/. Accessed 15 Nov. 2018.

UN Report.Pdf.

“Students Use GoFundMe to Try to Pay for College.” Cleveland.Com, 20 Feb. 2017, http://www.cleveland.com/metro/index.ssf/2017/02/college_students_seeking_funds.html.

“University of Kentucky Plans to Privatize Its Dining Services.” Kentucky, https://www.kentucky.com/news/local/education/article44469855.html. Accessed 25 Oct. 2018.

Vehicle Ownership in U.S. Cities Data and Map. http://www.governing.com/gov-data/car-ownership-numbers-of-vehicles-by-city-map.html. Accessed 17 Nov. 2018.

Why Private Equity Is Furious Over a Paper in a Dermatology Journal – The New Yo.Pdf.

Woodman, Spencer. “Uber Wants to Take over Public Transit, One Small Town at a Time.” The Verge, 1 Sept. 2016, https://www.theverge.com/2016/9/1/12735666/uber-altamonte-springs-fl-public-transportation-taxi-system.

About the Author

Robin DeRosa is the director of the Open Learning & Teaching Collaborative at Plymouth State University in New Hampshire. She is an internationally recognized leader in open pedagogy and an advocate for public higher education in the United States. She can be found at her website, www.robinderosa.net, or on Twitter @actualham.

Attribution