17 Open Education, Open Questions

Catherine Cronin

This article was adapted from my keynote presentation at the 2016 Open Educational Resources Conference OER16: Open Culture at the University of Edinburgh and from the related post on my blog, catherinecronin.net.

The use of open practices by learners and educators is complex, personal, and contextual; it is also continually negotiated. Higher education institutions require collaborative and critical approaches to openness in order to support faculty, students, and learning in an increasingly complex higher education environment.

Whether we consider ourselves to be open education practitioners or researchers, advocates or critics, wonderers or agnostics, our motivating questions regarding openness are likely to be different, often very different. For example: How can we minimize the cost of textbooks? How can we help students to build, own, and manage their digital content? How might we support and empower learners in making informed choices about their digital identities and digital engagement? How might we build knowledge as a collective endeavor? And, how can we broaden access to education, particularly in ways that do not reinforce existing inequalities? Open educational practices can help us in achieving these aims. However, engaging with the complexity and contextuality of openness is vitally important if we wish to be keepers not only of openness but also of hope, equality, and justice.1

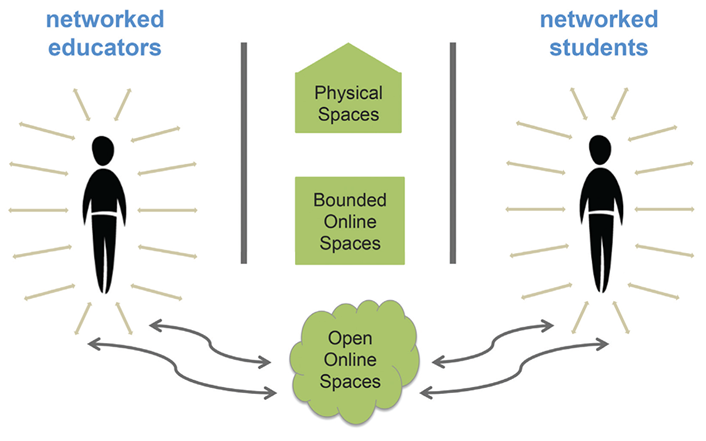

At present, open practices sit somewhat uneasily and unevenly within higher education. As Bonnie Stewart notes: “The word ‘open’ signals a broad, de-centralized constellation of practices that skirt the institutional structures and roles by which formal learning has been organized for generations.”2 Teaching and pedagogical interactions typically occur in higher education in one or more of the spaces illustrated in figure 1: physical spaces; bounded online spaces; and open online spaces. This is a simplification, of course, but useful for the purpose of comparison. There are good reasons for teaching and learning to occur in each of these spaces, depending on our particular aims and context. However, if we limit ourselves to the first two spaces, it is difficult to share our learning with wider networks and difficult to invite our networks to participate in the dynamic learning spaces we create. This is not simply a matter of, say, choosing to use Facebook simply because “that’s where our students are” (which is not a valid assumption in any case). It’s about recognizing the ubiquity of knowledge across networks, the importance of developing network as well as digital literacies, and the imperative of facilitating learning that fosters agency, empowerment, and civic participation.

The Open Education Consortium defines open education as “resources, tools and practices that employ a framework of open sharing to improve educational access and effectiveness worldwide.”3 Beyond this overarching definition, however, openness is a complex phenomenon, with economic, political, technical, and social aspects. The qualifier “open” is variously used to describe resources (the artefacts themselves as well as access to and usage of them), individual learning and teaching practices, institutional practices and policies, the use of educational technologies, and the values underlying educational endeavours.

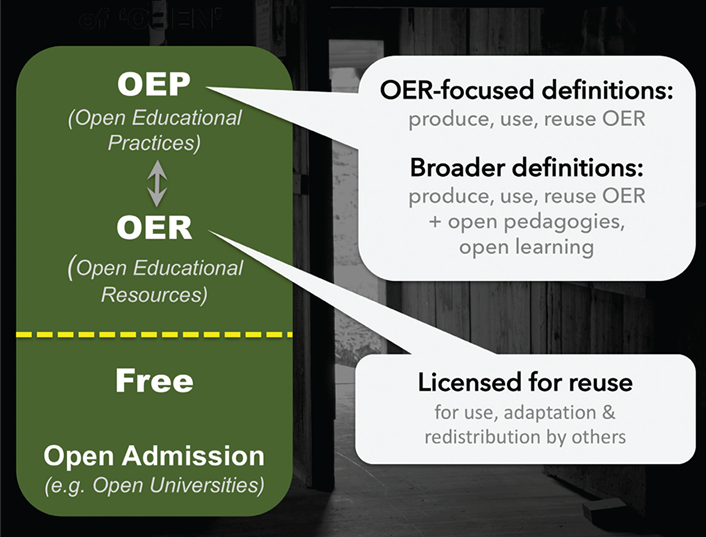

So how do we grasp openness? A first step is to be clear about our own aims and interpretations. I’ve often used a simple typology of interpretations of openness (see figure 2) to contextualize and compare others’ work and to communicate my own. The first interpretation of openness in education is open admission, where the qualifier “open” refers to open-door academic policies, such as those of The Open University in the United Kingdom and dozens of open universities globally. A second interpretation is open as free. Using this interpretation, a vast array of online resources and courses would be considered open: YouTube videos, podcasts, TED Talks, and MOOCs, for example. Free resources are not unfettered, however. They can be accessed only by those with the requisite skills, device(s), and Internet connection. Users are often required to register in order to access free resources, providing personal information such as a name and e-mail address. In such cases, even though the resources are free, they have an opportunity cost to the user in the form of personal data and usage data.4 In addition, the use of free online resources is subject to copyright restrictions unless the creators provide explicit permission for reuse of the original works. Many open education advocates and researchers thus consider the “open as free” interpretation to be limited.

Two further interpretations of “open” are OER (Open Educational Resources) and OEP (Open Educational Practices). OER are resources whose creators have expressly enabled reuse through the use of open licenses. OER embody the notion of knowledge as a public good: take it, use it, remix it, and share as you wish. OEP move the focus beyond content. OEP are “practices which support the (re)use and production of OER through institutional policies, promote innovative pedagogical models, and respect and empower learners as co-producers on their lifelong learning paths.”5 The most expansive definitions of OEP focus on OER, open pedagogy, and open learning, as well as power relations and inequality.6

The deceptively simple term open hides a great deal of complexity, much of which depends on the particular context within which open practice is considered. Thus it is imperative to move beyond open-versus-closed dichotomies and even beyond unified conceptions of openness. Openness requires a critical approach.

We must be aware of the potential for openness to do the opposite of what we intend and to create or exacerbate inequalities. Students and faculty who are already marginalized, structurally or otherwise, can feel pressured to take on open scholarship and may be disadvantaged by it — exposing themselves to online abuse, for example. As Richard Edwards writes: “Openness is not the opposite of closed-ness, nor is there simply a continuum between the two. . . . An important question therefore becomes not simply whether education is more or less open, but what forms of openness are worthwhile and for whom; openness alone is not an educational virtue.”7 Openness entails negotiating new forms of risk. sava singh, for example, highlights the privilege of many open educators: “The people calling for open are often in positions of privilege, or have reaped the benefits of being open early on — when the platform wasn’t as easily used for abuse, and when we were privileged to create the kinds of networks that included others like us.”8 We may feel comfortable in the networks we have created, and enthused about inviting peers and students, but open practice is always personal. Individual determinations regarding openness often entail a succession of considered and nuanced decisions within specific contexts. Recognition of the complexities and risks of openness, as well as its potential benefits, should inform open education practice and policy. A critical and reflexive approach is essential.

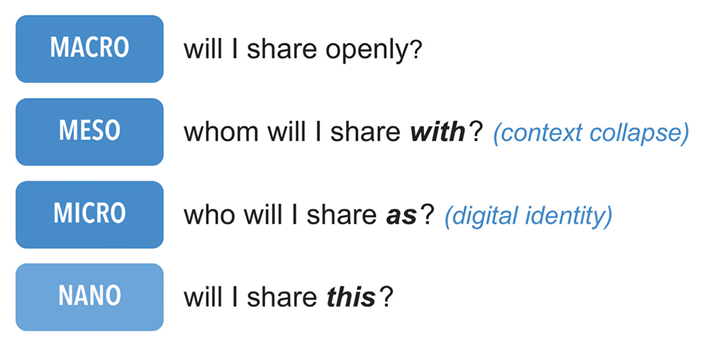

In my own research, I have explored meaning-making and decision-making by college and university educators regarding whether, why, and how they use OEP in their teaching.9 Among the educators I interviewed (across a continuum of “closed” to open practice), the issue of most concern was balancing privacy and openness — which was overwhelmingly described as both an individual decision and an ongoing challenge. In the words of one academic: “You’re negotiating all the time.” Through this research, as well as ongoing work with faculty and students, I’ve found that individuals seek to balance privacy and openness in their use of social and participatory technologies at four levels (see figure 3): macro (global level), meso (community/network level), micro (individual level), and nano (interaction level).

Considering these different levels has proved helpful to me in understanding the personal and complex negotiations involved in open practice. At the macro level, individuals make decisions about whether or not to engage in open networking and sharing, for example via Twitter or blogging. Some individuals opt out at this level. Those who engage further in open practice must consider questions at three additional levels. At the meso level, individuals consider whom they would like to share with (e.g., family, friends, faculty, students, interest groups, the wider public), as well as those with whom they do not want to share. At the micro level, individuals make decisions about their digital identities — that is, who they will share as. And at the nano level, individuals make decisions about individual open transactions: “Will I like, follow, friend, post, tweet, tag, or share this?” Think, for example, of those moments when you’ve hovered over your keyboard or phone before pressing “Send.” As one academic in my research study put it: “It’s a lot of work for one tweet.” Formal and informal professional development initiatives often focus at the top or macro level, describing the benefits of sharing and supporting staff in learning how to use various tools. But the complex and ongoing work of open practice happens beneath this level — at the meso, micro, and nano levels — where issues around context collapse and digital identity are negotiated.

In summary, openness does not involve a one-time decision, and it is not universally experienced. It is always complex, personal, contextual, and continually negotiated. Attention must be paid to the actual experiences and concerns of students and faculty. Critical approaches are essential. I believe we must support faculty and students by working broadly and collaboratively in three key areas: developing digital literacies and digital capabilities;10 specifically supporting individuals in navigating tensions between privacy and openness; and, most critically, reflecting on the role of higher education and the roles of and relationships between educators and students in an increasingly open and networked society.

Notes

- The idea of being the “keepers of justice” is inspired by Tressie McMillan Cottom, “The Access Paradox: Can Education Expansion Balance Access with Equality?,” Keynote, International Conference on Open and Distance Education, University of South Africa, October 14, 2015, and Paul Prinsloo, “Making Sense of Access: Access to What? At What Cost? For Whom?,” Open Distance Teaching and Learning, October 26, 2015.

- Bonnie Stewart, “Open to Influence: What Counts as Academic Influence in Scholarly Networked Twitter Participation,” Learning, Media and Technology 40, no. 3 (2015).

- “What Is Open Education?” Open Education Consortium (website), accessed August 29, 2017.

- Cheryl Hodgkinson-Williams and Eve Gray, “Degrees of Openness: The Emergence of Open Educational Resources at the University of Cape Town,” International Journal of Education and Development Using Information and Communication Technology 5, no. 5 (2009).

- Ulf-Daniel Ehlers, “Extending the Territory: From Open Educational Resources to Open Educational Practices,” Journal of Open, Flexible and Distance Learning 15, no. 2. (2011).

- See, for example, H. Beetham, I. Falconer, L. McGill, and A. Littlejohn, “Open Practices: Briefing Paper,” Jisc, 2012; Laura Czerniewicz, Andrew Deacon, Michael Glover, and Sukaina Walji, “MOOC-making and Open Educational Practices,” Journal of Computing in Higher Education 29, no. 1 (April 2017); Cheryl Hodgkinson-Williams, “Degrees of Ease: Adoption of OER, Open Textbooks and MOOCs in the Global South,” Keynote, OER Asia Symposium, Penang, Malaysia, June 25, 2014.

- Richard Edwards, “Knowledge Infrastructures and the Inscrutability of Openness in Education,” Learning, Media and Technology 40, no. 3 (2015), 253.

- sava saheli singh, “The Fallacy of ‘Open,'” savasavasava, June 27, 2015.

- Catherine Cronin, “Openness and Praxis: Exploring the Use of Open Educational Practices in Higher Education,” International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 18, no. 5 (2017).

- See, for example, Helen Beetham, “Revisiting Digital Capability for 2015,” Jisc Digital Capability Codesign Challenge Blog, June 11, 2015; Cheryl Brown, Laura Czerniewicz, Cheng-Wen Huang, and Tabisa Mayisela, “Curriculum for Digital Education Leadership: A Concept Paper,” Commonwealth of Learning (COL), 2016; All Aboard: Digital Skills in Higher Education (website).

About the Author

Catherine Cronin is Strategic Education Developer at Ireland’s National Forum for the Enhancement of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. Catherine brings many years’ experience as an open educator, open researcher, community educator and activist to her work in higher education. Her work focuses on digital and open education, critical approaches to openness, critical digital literacies and digital identity practices. Her recent PhD explored the benefits, risks and tensions of using open educational practices (OEP) in higher education. A born New Yorker who has made her home in Ireland, you can find Catherine online at @catherinecronin.

Other works:

Open education, walking a critical path

Open education: Design and policy considerations

Framing open educational practices from a social justice perspective

Attribution