13 Stress and Coping

Luciano Berardi; Olya Glantsman; and Christopher R. Whipple

Chapter Thirteen Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Understand what stress is and the different forms people can experience

- Understand what coping is, what coping strategies are, and coping styles

- Understand how individuals and communities become resilient

It’s 2:00 a.m. and your head is swarming with thoughts, none of them pleasant or relaxing: Did I reply to that important email? Am I ready for the upcoming presentation? Should I have studied more for tomorrow’s test? How long will it take me to fall asleep? Why is this always happening to me? All of these thoughts manifest as stress, an ever-present variable in our lives. You are not alone and as you will find out in this chapter, there are ways of coping and managing these stressors. Furthermore, there are ways that we can help communities better deal with these types of challenges.

WHAT IS STRESS?

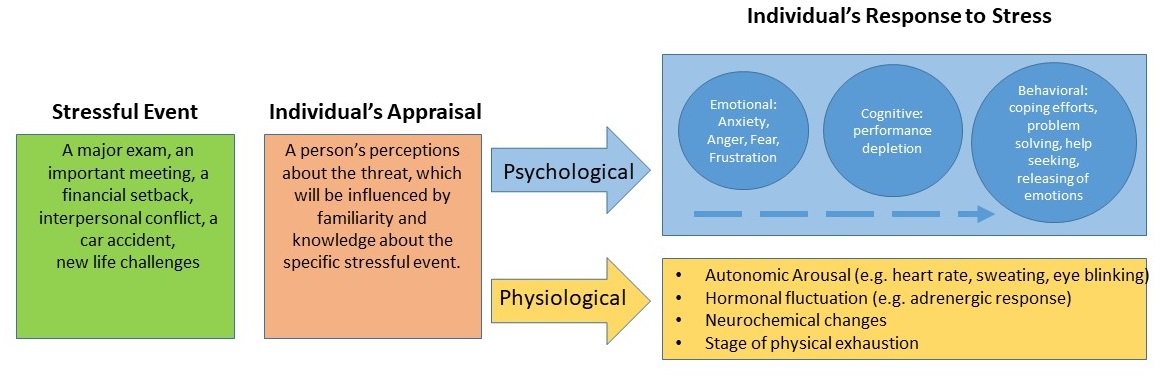

So what is stress? This shouldn’t be a trick question, but why is it so hard to answer? Stress can be three things: a stimulus event (i.e., a stressor), a process for understanding the stimulus and its context, and a reaction we have to this event. Essentially, to be stressful the event has to become an overload of incoming information into our system. Stress can cause biological responses such as sweaty palms or a racing heart, as well as psychological responses such as nervousness. It is known to have effects on our behavior causing us to avoid others, and it also affects cognitive performance causing us to have difficulty concentrating.

A number of genetic studies have begun to identify candidate genes that may play a role on diverse forms of stress reactions. It is highly probable that genetics account for some of our responses to stress, but other factors are also of importance. Environmental stressors can also affect our behaviors and emotions. Environmental stressors can be grouped into different types: Major Life Events (e.g., experiencing a breakup, getting married, or having a baby), Life Transitions (e.g., puberty or transition into high school), Daily Hassles (e.g., family arguments or waiting in a long line at a security checkpoint of an airport) and Disasters (e.g., experiencing a car accident or a computer crashing causing loss of important information). These types of environmental stressors can cause you to be fearful and have a racing heartbeat. And our perceptions of these responses can actually make the symptoms worse. It is also important to note that these stressors can be perceived differently by different people. For instance, two people can get stuck in the same elevator and while one would find the experience to be a nuisance, another will tell you it was the worse situation they have ever been in. Here is a poll about the role of stresses and stress responses in the natural world. This supplementary article explores what is the right amount of stress.

PHYSIOLOGICAL VS PSYCHOLOGICAL STRESS

While most of the time we think about stress in a negative way, some stress is adaptive and can even give us an edge. Part of the stress reaction involves the secretion of hormones, which in turn will stimulate the cardiovascular system, which includes your heart. In this way, the right amount of stress may release hormones and increase our ability to focus better on an exam or to quickly maneuver our car when we are trying to avoid an accident. Most stressors in our daily life are psychological in nature—dating, exams, presentations, and deadlines, so the adrenaline and cortisol (i.e., stress hormones) released into the bloodstream do not get burned off. These types of psychological stressors can initiate an over-activation with a tendency to make the stress response worse. So, a response to an environmental stressor may start as fear and turn into a panic attack.

Acute vs Chronic Stress

One of the goals of our body is to maintain stability (i.e., homeostasis). We can, therefore, define stress as an actual or perceived threat capable of throwing our homeostasis off balance. Stress exposure starts the responses. When a person is exposed to prolonged stress, overload may occur. When the stress response is triggered too often and/or remains active too long, it can cause “wear and tear” on the body from lowering your immune system and bone density, to hypertension, to heart attack.

There are two different types of stressors that we typically encounter. Acute stressors are observable stressful events that are time-limited such as an upcoming test or a family gathering. An acute stressor brings activation to our neuroendocrine system and makes us ready to act (i.e., “fight or flight”). Remember that pumped up feeling you got the last time you were getting ready to give a speech in front of the class? Chronic stressors, in contrast, are persistent demands on you; they are typically open-ended, using up your resources in coping but not having any resolution. Here is a short article and podcast on stress effects on health and suggestions for stress preventive activities.

A chronic illness, poverty, and racial discrimination are all examples of chronic stressors. Prolonged stress can lead to an eventual breakdown, causing one to be unable to take care of oneself or work. A number of recent studies have shown that lower socioeconomic status is associated with higher stress load. In addition, perceptions of racism can serve as a chronic social stressor for ethnic minorities and can, in part, explain some of the health issues of African Americans and other ethnic minority groups in the US and other countries.

Everyday Hassles

Robert Service, a Canadian Poet, cautioned, “Be master of your petty annoyances and conserve your energies for the big, worthwhile things. It isn’t the mountain ahead that wears you out—it’s the grain of sand in your shoe.”

In addition to many stressors in our lives being psychological and chronic in nature, we should pay attention to everyday hassles, which can be as harmful, if not more harmful than life-changing events. Everyday hassles may include things like worrying about one’s weight, having too much work with too little time, or a stressful commute to school or work. Major life changes usually bring about more hassles, which may lead to more physical stress symptoms.

In summary, stress can be adaptive—in a fearful or stress-causing situation, we can run away to save our lives, or we can concentrate better on a test. Biologists might even say it is necessary. But, stress can also be maladaptive. This is especially true if it is prolonged (i.e., chronic stress) because it increases our risk of illness and health problems. Thus, reducing stress, especially prolonged stress, is essential to healthcare. This video explains the effects of daily hassles on our health.

COPING AND STRESS

To deal with stress in your life, it is important to figure out where that stress originates and notice how you tend to react to it. Later in this chapter, we will show you how community psychologists consider the environment and ecological perspectives as intertwined in stress and coping. Lazarus and Folkman (1984) have been among the most influential psychologists in the stress and coping field, and they defined coping as efforts to manage demands that could exceed our resources. It is important to highlight from this definition that when a person perceives a life circumstance as taxing and exceeding the resources they have, this person will experience stress. Therefore, coping involves your efforts to manage stress, which is illustrated in Figure 1.

Coping Defined

Lazarus and Folkman (1984) felt that when humans perceive a life circumstance as taxing and exceeding their resources, stress will be experienced, which we have already defined in the prior section as an overload of incoming information into a system. Therefore, coping involves persons’ efforts to manage stress, whether the process of dealing with stress is adaptive or not (Lazarus, 1993). When we talk about coping, we will need to consider the intensity of the stressor, the context of coping, and an individual’s appraisal of coping expectations.

Coping Types

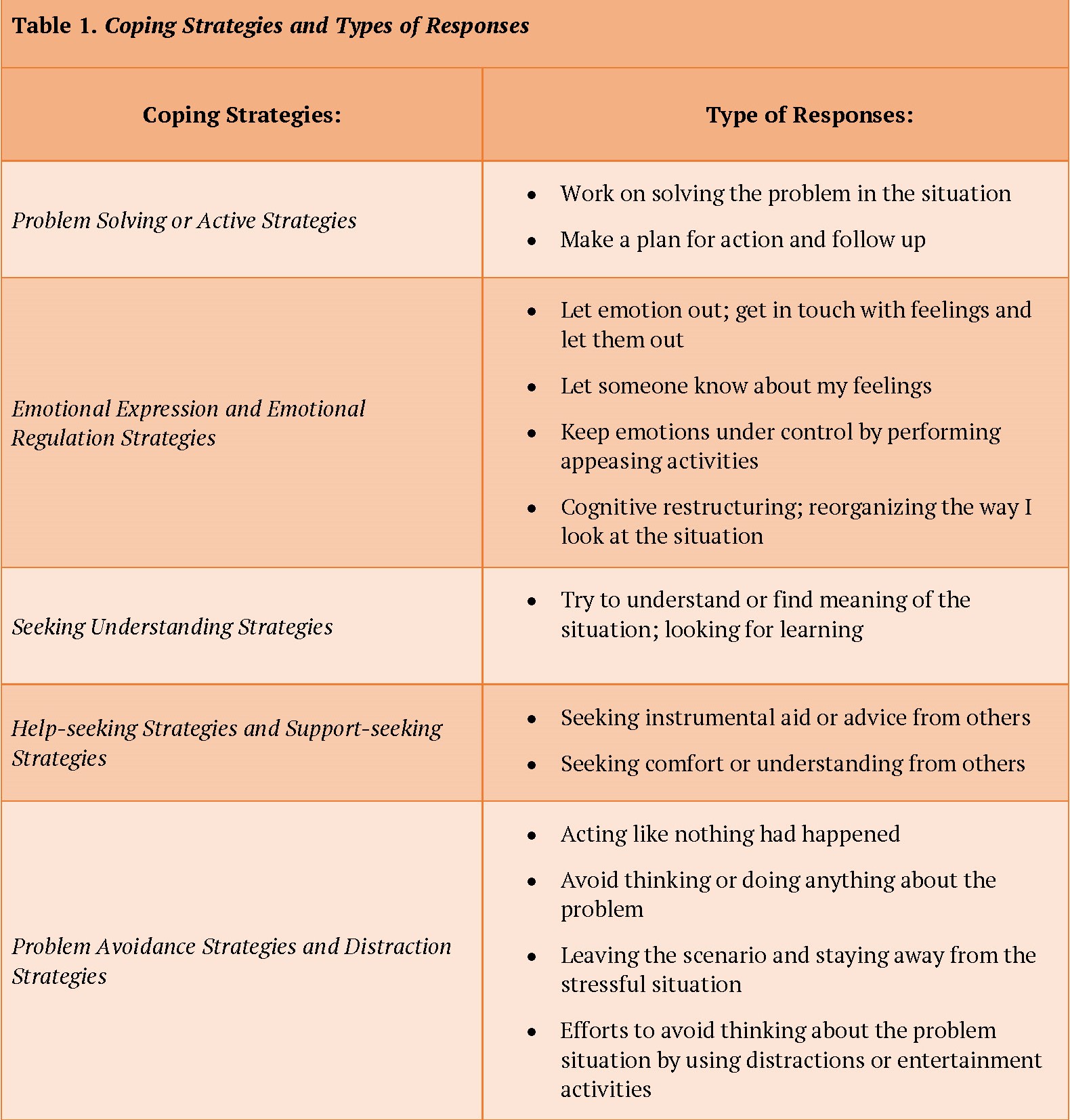

Research on coping has usually found five types of coping styles (Clarke, 2006; Skinner, et al., 2003; Folkman & Moskowitz, 2005). These include the following: (1) problem-focused coping style involves addressing the problem situation by taking direct acting, planning or thinking of ways to solve the problem, (2) emotion-focused coping style involves expressing feelings or engaging in emotional release activities such as exercising or practicing meditation, (3) seeking-understanding coping style refers to finding understanding of the problem and looking for a meaning of the experience, and (4) seeking help involves using others as a resource to solve the problem. Finally, people might respond to stressors by (5) avoiding the problem and trying to stay away from the problem or potential solution to the problem.

Coping Strategies

Coping strategies are the choices that a person makes in order to respond to a stressor. A strategy can be adaptive (effective) or maladaptive (ineffective or harmful). The ideal adaptive coping strategy varies depending on the context, as well as the personality traits of the person responding. The coping strategies can be problem-solving or active strategies, emotional expression and regulation strategies, seeking understanding strategies, help or support-seeking strategies, and problem avoidance or distraction strategies.

Here is one example of an intervention strategy that shows how to effectively cope with daily and transitional stressors. The strategy is called Shift-and-Persist (Chen & Miller, 2012), and it requires individuals to first shift views of the problem. To shift, you need to (1) recognize and accept the presence of stress, (2) engage in emotional regulation and control negative emotions, and (3) practice self-distancing from the stressor to gain an outsider’s perspective of the stressful context. To persist, you would need to (1) plan for the future through goal setting, (2) recognize a broader perspective when obstacles arise, (3) determine what brings meaning to your life, and (4) become flexible to determine new pathways to goals. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association offer other coping strategies. Two more discussions on coping strategies are found in these two Ted Talk Videos here and here.

Table 1 below presents a list of coping strategies and is a summary of strategies reported in Clarke, 2006; Skinner, et al., 2003; Folkman & Moskowitz, 2005. Although completed lists are more extensive, this table presents styles reported across the three studies that presented similar types of responses.

To understand coping as a process, we need to understand people’s reaction to stress in context. This includes assessing whether the coping thoughts or actions are good or bad for that given challenge and given context. In addition, the process of coping includes the particular person, the particular encounters with the stressor, the time of the person’s reactions, and the outcome being examined. Practical Application 13.1 can help you examine your reaction to stress and understand your coping process.

Practical Application 13.1

Understanding Stress in Your Life

Think about an important stressful experience in your life:

- What was stressful about it for you?

- Was it a short-term or a long-term situation?

- What thing did you do to cope with this experience?

- What resources helped you cope with this stressful experience?

- How did your experience affect you as a person?

- What did you learn or how did you grow through this experience?

COPING AND CONTEXT

Community psychologists try to understand coping beyond individual perceptions and reactions to stress. In general, new coping models are looking into what the characteristics of people that will elicit a given coping style are. In addition, it is important to learn more about the effectiveness of different coping styles when used across different contexts (which includes the environment and nature of the stressors). A community psychologist is interested in understanding the contextual element that produces or reduces a given stressor, so they create interventions to help people cope with their stressors. Finding the best fitting coping strategy may improve people’s experiences and outcomes when confronted with challenging/stressful life transitions.

All people are exposed to transitions, with youth being even more likely (e.g., starting elementary/middle school, finishing high school, first job, etc.), and the experience of mastery of these situations might help school-age youth successfully cope with future transitions. The following Case Study 13.1 highlights how community psychologists might use preventive strategies to help youth deal with these types of natural stressors that they will encounter in life.

Case Study 13.1

Preparing Students for High School Graduation

Leonard Jason and Betty Burrows (1983) provided youth about to graduate from high school with practice crisis experiences to work through, so that they could generate successful outcomes for stressful situations. The youth were first informed that during times of transition, heightened levels of emotions are often experienced. These elevated levels of arousal can become maladaptive if experienced over a prolonged period of time. They then had a chance to practice techniques to effectively reduce excessive arousal or anxiety such as progressive muscle relaxation, meditation, or listening to quiet music. The youth were then given anxiety-promoting transitions to imagine. They were asked to try one of these strategies to alleviate the anxiety of this crisis situation.

The seniors also had a chance to discuss how personal beliefs and self-statements can affect one’s mood. When difficult transitions are encountered, irrational beliefs or negative self-statements might arise. An example of an irrational belief is that it is a necessity for us to be loved and approved by everyone we know. The seniors were provided with situations involving transitions to role-play. Within each of these scenes, one actor adopted an irrational belief; the other attempted to show a more rational way of thinking. Following each role-play, the participants had a chance to discuss how the adoption of a rational or irrational belief might affect their ability to successfully handle transitions. Following the role-plays, all the students discussed how effective the various coping strategies might have been in resolving transitional events.

This study found that seniors about to graduate from high school can profit from being provided a preventive intervention that prepares them for dealing with transitions. Here are some of the students’ comments: “You really helped me to really think out all my problems and how to answer them. Thanks!! …. It helped me to help other people who are in difficult situations.” “I think that problem solving is the most helpful to people at my age because we face problems every day.” “I feel that I have benefited from the sessions as I have gone through a lot as my mother has been divorced twice and is married for the third time and I just moved from a small town to a large city.”

But sometimes, crises occur, and then we need to find ways to deal with those situations. Case Study 13.2 will provide an example of helping individuals and communities with dealing with a natural disaster, Hurricane Maria.

Case Study 13.2

Coping with Hurricane Maria

On September 20th, 2017, Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico. Watching the compounding difficulties over the course of that fall, Melissa Ponce-Rodas and a team of 20 members, four faculty, one alumna, 13 students, and two other staff members with backgrounds in undergraduate and graduate psychology, community and international development, and social work decided to spend their Spring break helping with the recovery. The ultimate goal of the mission was to “Accept, Talk, Heal,” providing mental health training in churches and communities to give those affected by the disaster the tools they needed to help them through the trauma of the aftereffect of the hurricane and to help them recover beyond the physical reconstruction of their community. This intervention was about more than cleaning up debris or restoring a school, it was about empowering a community to overcome trauma.

Prior to the intervention, the team contacted local church agencies and asked about their experiences and what was truly needed. This process of inquiry resulted in another group of people with expertise in the community to be invited into the collaborative process. The local collaborators included social workers, police officers, certified nursing assistants, staff from the four schools, church groups, and others who were directly affected by the natural disaster. It is not surprising that the team was quickly accepted and trusted by the community. Ponce-Rodas believes one contributor to this is her Puerto Rican heritage that helped bridge the intervention team to the community and facilitate connections between community members and those from the mainland.

Understanding the complexity of the coping process was one of the reasons Dr. Ponce-Rodas drew on her Community Psychology experience to partner with existing agencies on the island. Because so many community members had experienced symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder the intervention aimed at normalizing the emotional reactions affecting the individuals. The team reminded the community members participating in the intervention that the whole community was going through this and no one should feel isolated in their experience, and that it is normal to seek help from others when faced with adversity. The team emphasized this with the “Healing is a Process” slogan, highlighting the dynamic nature of this concept.

The team also agreed that a strength-based approach fits this intervention well. To help combat the loss and desperation, the community participants were encouraged to turn to the strengths the community still had. The message across the island was “Puerto Rico Se Levanta” (Puerto Rico Will Rise). Many heroic stories of selflessness and self-sacrifices emphasized resilience in the wake of such massive destruction and highlighted the power and strength in the community. The community members also often commented on their faith, which meant that the team included faith in their intervention. The team firmly believed that the best way the community could get help was by understanding the community’s background, by recognizing the dynamic process of coping, by alleviating the stigma of help-seeking, by drawing on their own strengths, and by helping themselves.

Coping and Support

Coping can be aided by asking others for support to help overcome problems. Support-seeking strategies include seeking advice or information or direct assistance. Individuals who engage in these types of help-seeking strategies are more likely to obtain social support. Seeking help from relatives may prove to be successful, which might contribute to it becoming a frequently employed coping mechanism. Barker (2007) suggests that youth’s help-seeking behaviors set up the conditions to create a rich supportive network for them, and the feeling that there is available support. Case Study 13.3 illustrates how one can go about studying supports using multiple points of view.

Case Study 13.3

Support Seeking Behavior

Having at least one friend in a recovery home was found to be about the best predictor among residents of recovery homes of having a good outcome, which involves not using drugs or engaging in illegal activities. To better understand what seeking support might be about, several community psychologists used focus groups to better understand natural friendship and mentoring relationships. For example, participants were asked about how they determined who they would go to in the house for support, the type of support they received from housemates, and the characteristics that those individuals have. The findings from the focus groups had a theme of promoting social support within their recovery homes, as one female participant explained:

“When I come in this door and I’ve got something to talk about, I don’t care which of these girls is here, I’m just going to talk about it. And that’s because they play a positive mentor or role model in my life. I don’t have to pick out two or three or one to say who I want to talk to.”

Instrumental supports were often related to the ability of other house members to provide tangible support for residents. As one female participant described:

“I have not been employed . . . I’ve always been concerned about if my rent’s going to get paid on time. These sisters came together and told me if you can’t get your rent paid, we know what you’re doing and we know that you want to be here and they were willing to go into their own pockets to help me pay my rent.”

Focus-group themes indicated that men were also able to form supportive relationships within the recovery home settings, but not as quickly as the females (Lawlor et al., 2014).

RESILIENCE

Individuals who experience significant and chronic stressors are often referred to as being “at-risk” of something, whether it be poor school performance, problems with alcohol or drugs, or engaging in illegal activities. However, not all individuals “at risk” of negative outcomes end up struggling with the outcomes. Some people are able to avoid negative outcomes and even thrive despite the adversity they face. Why is it that some people are successful in spite of seemingly insurmountable obstacles?

This question was at the heart of early studies of resilience. Resilience is a dynamic process characterized by positive outcomes despite adversity or stress (Luthar et al.,2015). In other words, resilience refers to how people maintain, or in some cases develop, healthy and positive outcomes in spite of stressful situations. The study of resilience stemmed from researchers who began to notice that a subset of their participants, often children facing significant adversity, did well despite their difficult circumstances. For example, Garmezy (1974) studied children of parents with schizophrenia. Among this group of at-risk children, all were expected to struggle in various aspects of life and likely develop schizophrenia. But a subset of children exhibited surprisingly positive and adaptive behavioral patterns despite their level of risk. Another large-scale study recruited all of the children born on the island of Kauai, Hawaii (Werner, 1996). The original goal of the study was to assess the long-term consequences of stressful living environments (e.g., family discord, divorce, parental alcoholism, mental illness). Most of the children living in these stressful environments struggled academically and behaviorally. However, one-third of these “high-risk” children did not develop learning or behavioral problems; in fact, many of them thrived. Studies like these helped to shift our focus from a deficits-only approach to one more able to consider both deficits and strengths.

Resilient children were thought to have been invulnerable and able to weather any storm. Traits found to characterize resilience include high creativity, effectiveness, competence, and ability to relate well to others. Now, resilience is viewed as the interaction between the person and their environment, and given the right combination of individual and environmental supports, it might be possible for anyone to be resilient. From a Community Psychology perspective, research had found that these children are positively affected by their immediate and extended family networks and religious organizations (Wright et al., 2013).

“Resilience does not come from the rare and special qualities, but from the everyday magic or ordinary, normative human resources in … children, in their families and relationships, and in their communities.” (Masten, 2001, pp. 235)

So far, we have considered resilience as an individual construct. Individuals can be resilient to adversity. However, it is also possible to apply this idea of resilience to groups of people. Community resilience is the collective ability of a defined group of people to deal with change or adversity effectively (Aldrich & Meyer, 2015). When adversity, like a disaster, financial struggle, or war strikes a community, will the community as a whole be able to overcome and bounce back?

Resilient communities often have many characteristics in common. Communities that are resilient frequently have access to both resources and relationships that support resilient outcomes. An important element of community resilience includes members’ knowledge of their own community, both its weaknesses and strengths. In addition, resilient communities have strong community social networks in which people work together to achieve goals, with competent governance and leadership. Often there is also an economic investment, both before and after adversity strikes. Another important factor is individual, family, and government preparedness. And finally, resilient communities have positive attitudes and an acceptance of change (Patel et al., 2017). Both research and community work is now being done to help communities build these resources and relationships to protect against adversity.

Case Study 13.4

Promoting Community Resilience

From 2000 to 2010, poverty rates in the Belmont Cragin neighborhood in Chicago doubled. Consisting of 80% Latino residents, Belmont Cragin residents have experienced soaring poverty rates associated with the gentrification of nearby neighborhoods. In addition, many residents in the neighborhood experienced significant trauma when they were younger. These adverse childhood experiences include living in extreme poverty; suffering physical, sexual, or emotional abuse; being exposed to community violence; having a parent struggling with substance abuse, or many other potentially traumatic experiences. Having adverse childhood experiences can be detrimental to emotional and physical health, and individuals who have experienced them are more likely to experience additional negative emotional or behavioral outcomes. In recognition of the increasing poverty in the neighborhood and the trauma experienced by many residents, community leaders formed the Resilient Belmont Cragin Community Collaborative. Community Psychologists Suzette Fromm Reed and Judith Kent worked with Belmont Cragin leaders to help residents cope with adverse childhood experiences by facilitating trauma-informed programming at schools using mentoring, tutoring, and counseling to help at-risk youth stay on track. They also helped train police to de-escalate the conflict. The Resilient Belmont Cragin Community Collaborative utilized existing community resources and established partnerships with resources outside of the community to ensure collective healing and growth. It brought together members of the community, from schools, health care settings, businesses, police departments, families, faith leaders, and others, to help residents address these traumatic experiences and thrive. Programs like these exemplify community resilience and help individuals, and the community as a whole, grow and heal together.

The concept of posttraumatic growth is centuries old, but was introduced to the fields of psychology and psychiatry in 1995 (Tedeschi, Shakespeare-Finch, Taku, & Calhoun, 2018). Over several decades of research, Tedeschi et al. found that many individuals who suffer various types of trauma experience psychological growth. The term posttraumatic growth (PTG) is separate and distinct from resilience. People who are resilient tend to be relatively unaffected by the effects of trauma and tend to bounce back quickly when faced with adversity. The process and outcome of PTG is generally seen in people who struggle psychologically following the aftermath of their trauma. As individuals begin to reconstruct their beliefs about life, themselves, and others, they come to appreciate the fact that they have become stronger, developed a greater capacity for relating to others, experienced immense gratitude, acknowledge new possibilities, and experience spiritual and/or existential growth.

Acknowledging Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) as a possible outcome of trauma is important, however, being too deficit-focused can hide the fact that many trauma survivors also experience post-traumatic growth. The same difficult experiences that lead to PTSD set the stage for psychological growth and the development of new strengths. Those who have endured natural disasters, violence, motor vehicle accidents, and many other types of trauma in their communities also experience posttraumatic growth. After facing incredible adversity they go on to provide social support and help others learn to grow from their struggles as well (Tedeschi, Shakespeare-Finch, Taku, and Calhoun, 2018).

Posttraumatic growth is usually experienced without the help of psychologists or other mental health professionals. Just as the symptoms of PTSD are naturally occurring reactions to the dire threats of trauma, and often diminish without the help of psychiatric professionals, posttraumatic growth is a naturally occurring process of healing and growth in the aftermath of trauma. Both are natural responses of the mind and body to the injury of trauma. However, informal support from people who listen well, wish to learn about a trauma survivor’s experience and see the possibilities for growth can help people see a path toward posttraumatic growth. Furthermore, mutual-support groups and community-based intervention training are showing promise toward expanding the opportunities and recognition of PTG more broadly (Moore, Tedeschi & Greene, 2020).

There is a need to apply this type of work to help those from disadvantaged neighborhoods and communities who frequently experience chronic stressors. This might be done by promoting the use of multilevel and interdisciplinary work that meshes with Community Psychology’s values of promoting social justice, as indicated in Chapter 1 (Jason et al., 2019).

SUMMING UP

We all experience stress. However, we respond to this stress in different ways. Sometimes low levels of stress can actually be helpful as it could motivate you to study for an exam. Although the experience of stress is very subjective, stress elicits physiological, emotional, and cognitive reactions in us all. To deal with these stressors, we mobilize resources for coping with the problems confronting us. The success of our coping efforts will depend on ourselves as well as the environmental challenge. For example, most of us have the resources to deal with the stress of a thunderstorm, but we might really be challenged if we are confronted with a tornado that comes through our neighborhood. So there are different levels of stressors that we face. In this chapter, we examined the relationship between stressors and coping, and we reviewed the different coping styles and the relationship between individual and context and coping outcomes, including resilience. We hope that this review of stress has provided you with some new insights about how you might use a variety of coping strategies to deal with stress and to work toward the reduction of stress among others.

Critical Thought Questions

- What are the most difficult stressors for you?

- With these most difficult stressors, what are the best ways you have found to cope with them?

- Are there people you go to when you are having problems at college? What are the ways they are helpful and what are the ways they might change to be even more helpful to you?

Take the Chapter 13 Quiz

View the Chapter 13 Lecture Slides

____________________________________________________________________

REFERENCES

Aldrich, D. P., & Meyer, M. A. (2015). Social capital and community resilience. American Behavioral Scientist, 59(2), 254–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764214550299

Barker, G. (2007). Adolescents, social support and help-seeking behavior. An international literature review and programme consultation with recommendations for action. Instituto Promundo, Brazil.

Chen, E., & Miller, G. E. (2012). “Shift-and-Persist” strategies: Why low socioeconomic status isn’t always bad for health. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(2), 135-158.

Clarke, A. T. (2006). Coping with interpersonal stress and psychosocial health among children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35(1), 11-24.

Folkman, S., & Moskowitz, J. T. (2005). Coping: Pitfalls and promise. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 745-774.

Garmezy, N. (1974). Children at risk: The search for the antecedents of schizophrenia. Part I. Conceptual model and research methods. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 1(8), 14- 90.

Jason, L.A., Glantsman, O., O’Brien, J. F., & Ramian, K. N. (2019). Introduction to the field of Community Psychology. In L. A. Jason, O. Glantsman, J. F. O’Brien, & K. N. Ramian (Eds.), Introduction to Community Psychology: Becoming an agent of change. https://press.rebus.community/introductiontocommunitypsychology/chapter/intro-to-community-psychology/

Jason, L. A., & Burrows, B. (1983). Transition training for high school seniors. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 7(1), 79-92.

Luthar, S. S., Crossman, E. J., & Small, P. J. (2015). Resilience and adversity. In R. M. Lerner, & M. E. Lamb (Eds.), Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science (7th ed.) (pp. 247-286). Wiley.

Lawlor, J. A., Hunter, B. A., Jason. L. A., & Rosing, H. B. (2014). Natural mentoring in Oxford House recovery homes: A preliminary analysis. Journal of Groups in Addiction Recovery, 52, 126–142.

Lazarus, R. S. (1993) Coping theory and research: Past, present, and future. Psychometric Medicine, 55, 234-247.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer.

Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56, 227-238.

Moore, B. A., Tedeschi, R. G., & Greene, T. C. (2020). A Preliminary Examination of a Posttraumatic Growth-Based Program for Veteran Mental Health. Practice Innovations. Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pri0000136

Patel, S. S., Rogers, M. B., Amlôt, R., & Rubin, G. J. (2017). What do we mean by ‘community resilience’? A systematic literature review of how it is defined in the literature. PLoS currents, 9, ecurrents.dis.db775aff25efc5ac4f0660ad9c9f7db2.

Wright M. O., Masten A. S., & Narayan A. J. (2013). Resilience processes in development: Four waves of research on positive adaptation in the context of adversity. In S. Goldstein, & R. Brooks (Eds.), Handbook of resilience in children. Springer.

Skinner E. A., Edge, K., Altman, J., & Sherwood, H. (2003). Searching for the structure of coping: A Review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychological Bulletin, 129(2), 216-269.

Tedeschi, R. G., Shakespeare-Finch, J., Taku, K., & Calhoun, L.G. (2018). Posttraumatic growth: Theory, research, and applications. New York: Routledge.

Werner, E. E. (1996). How children become resilient: Observations and causations. Resiliency in Action, 1(1), 18-28.

The process by which we perceive and respond to certain events that we appraise as threatening or challenging.

An ideal “set point” that depends on the person and context. The homeostatic process is a tendency toward a relative equilibrium between independent processes.

The “wear and tear” on the body when stress response is triggered too often and/or remains hyperactive too long.

Observable stressful events that are time-limited.

Persistent demands on an individual; typically open-ended, using up our resources in coping but not promising resolution.

The personality dispositions or traits that transcend the influence of the situational context and time when choosing coping strategies (Lazarus, 1993).

When the individuals respond with cognitive and behavioral efforts at managing or altering the problem causing distress.

When an individual responds with efforts to manage the emotional response to a stressful event by focusing directly on it in a constructive way.

When an individual responds by finding meaning and understanding, not seeking to put a positive interpretation on the problem, but to learn.

When an individual responds by using other people as a resource to assist in finding a solution, understand the problem, or express feelings of distress related to the problem.

Involves avoidant actions and cognitive avoidance, these strategies attempt to manage emotions by trying to avoid thinking about the stressor.

Refers to the effectiveness of a given coping response within a given context and for a given challenge or problem that the individual experiences as stressful.

A strategy for adapting to stress that requires individuals to first shift their views of the problem and themselves within the context of the problem/stressors.

Ongoing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage external or internal demands/problems/challenges perceived by the individual as stressful. The process for coping is influenced by the context where the demand arises, the time the stressors last, and how long before one responds.

Refer to approaches that explain the processes of how an individual handles a stressor(s). An individual’s coping model will be determined by cultural, social, and personality characteristics of people and will elicit a given set of coping strategies.

Strategies for coping with stress, which include seeking advice or information, or direct assistance from others.

Individuals who experience significant and chronic stressor events and are at-risk for developing associate physiological (e.g., cardiovascular complications) and psychological (e.g., anxiety, depression) symptoms.

A dynamic process characterized by positive outcomes despite adversity or stress.

The collective ability of a defined group of people or geographic area to deal with change or adversity effectively.