2 History

Paul A. Toro

Chapter Two Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Know major events in the history of Community Psychology

- Identify key perspectives that have vied for prominence in the field

- Be familiar with “founders” of Community Psychology

- Understand the future directions of theories and methodologies in Community Psychology

Any historical account (whether it involves politics, culture, or a profession) is bound to be subjective, so it makes sense that much of the history of the field of Community Psychology will also be subjective. Most existing Introductory Community Psychology textbooks (Jason et al., 2019) begin by discussing the social, political, scientific, and professional contexts that influenced the development of the field. Although we will review some of this history briefly, we will focus mainly on the past 50-plus years, since the term Community Psychology was first used by those attending what we now call the “Swampscott Conference” of 1965 (Bennett et al., 1966).

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

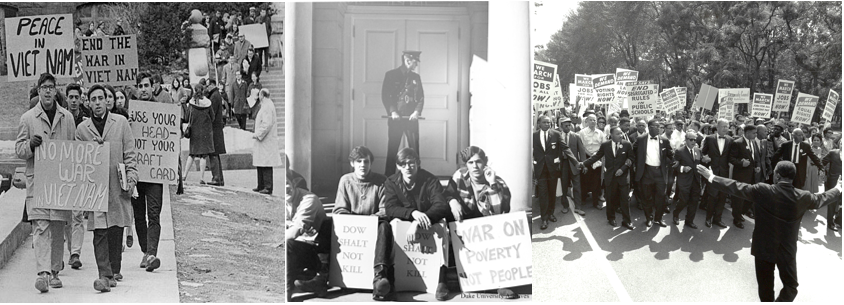

One needs to consider the social and political events of the 1960s in understanding the beginnings of Community Psychology. These were turbulent times, marked with protests and demonstrations involving the Civil Rights movement in the US. In 1965, the Voting Rights Act, an important accomplishment of the Civil Rights Movement, was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson. The Feminist Movement was also developing momentum during the 1960s and into the 1970s, as would a similar rights movement for gays and lesbians, the environmental movement, and widespread protests against the Vietnam war. This socially-conscious atmosphere was ideal for the development of the field of Community Psychology, whose values emphasized social justice.

During this time, there also was widespread deinstitutionalization of mental hospital patients, as various media accounts portrayed horrendous conditions within these settings. The development of antipsychotic medications such as Thorazine and the growing research evidence on the harmful effects of mental hospitalization (e.g., Asylums by Erving Goffman) were key factors in this movement. In 1961, the report of the Joint Commission on Mental Health and Illness was released, which recommended that we reduce the size of mental hospitals and train more professionals and paraprofessionals to meet the largely unmet need for mental health services in our society (Bloom, 1975). These recommendations, vigorously championed by President John F. Kennedy, led directly to the passage of the 1963 Community Mental Health Centers Act, which established community-based services widely throughout the nation. The Community Mental Health Movement was gaining momentum and many large state mental hospitals across the nation would be closed in the next 20 years. With these developments in the background, it was in 1965 that a group of clinical psychologists gathered in Swampscott, MA, and gave birth to the field of Community Psychology, which they hoped would allow them to become social change agents to address many of these pressing social justice issues of the 1960s. Click on this link for a more comprehensive description of events that led up to the Swampscott Conference.

THE FIRST DECADE: 1965-1975

In the years immediately after the 1965 Swampscott Conference, a number of training programs in community mental health and Community Psychology developed in the US. For example, Ed Zolik established one of the first clinical-community doctoral programs in the US at DePaul University in 1966. A free-standing doctoral program was also established in 1966 at the University of Texas at Austin by Ira Iscoe. By 1969, there were 50 programs offering some training in Community Psychology and community mental health, and by 1975 there were 141 graduate programs offering training in these areas.

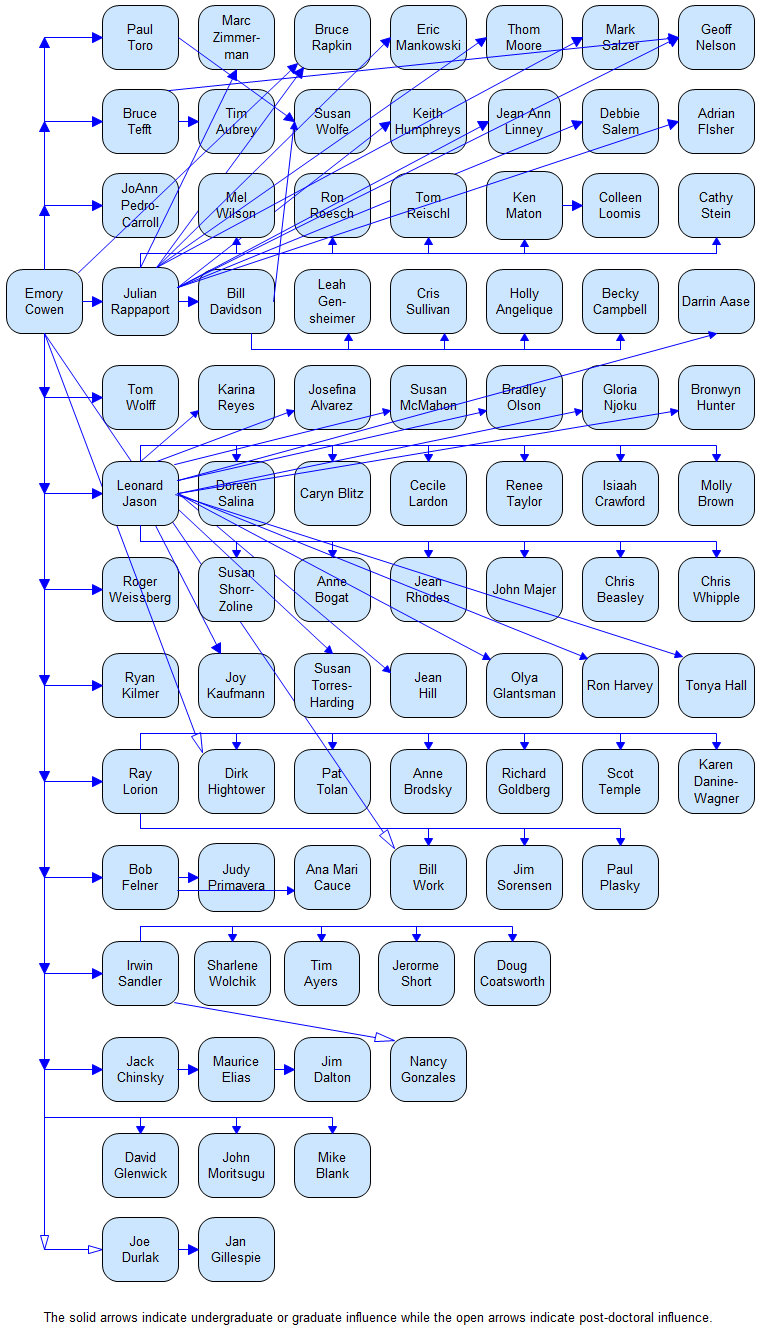

Several important “early settings” for community research and action also developed, often in connection with one of the training programs. These settings included the Primary Mental Health Project at the University of Rochester, founded by Emory Cowen (1975) (click here to see a video of Cowen describing this innovative program). The Primary Mental Health Project identified children in the primary grades (K-3) showing some initial trouble adjusting to school and provided help through the school year from paraprofessional child associates. Cowen, his graduate students, and staff built this intervention for a single school in Rochester in 1958 and it is used by 2,000 schools worldwide today. The Primary Mental Health Project was one of the first widely researched and publicized prevention programs developed by community psychologists. Cowen provided training for a large number of people who later would become prominent in Community Psychology (below is Cowen’s “family tree” initially developed by Fowler & Toro, 2008a).

The Community Lodge project, initially developed by George Fairweather at a Veteran’s Administration psychiatric hospital, was another of these important “early settings”. The Lodge provided an alternative to traditional psychiatric care by preparing groups of hospitalized patients in a shared housing environment for simultaneous release into the community. The released patients established a common business to support themselves (e.g., a lawn care service) and eventually took full control of the Lodge project from the professionals who helped them establish the Lodge initially. The first rigorous evaluation of the Lodge found that patients randomly assigned to the Lodge spent less time in a hospital than those in the control group who received traditional services (Fairweather et al., 1969). Fairweather later helped to establish the doctoral program in Ecological Psychology at Michigan State University and also provided training for many community psychologists.

In 1966, just a year after the Swampscott Conference, Division 27 (Community Psychology) of the American Psychological Association (APA) was established. Shortly after, James Kelly (1966), one of the Swampscott attendees and another “founder” of Community Psychology, published an article on the ecological perspective in the widely circulated American Psychologist. Like Cowen and Fairweather, Kelly has been important in training a large number of community psychologists.

The Journal of Community Psychology and the American Journal of Community Psychology were both first published in 1973. These journals have become the two most influential professional journals in the field. The first Community Psychology textbooks came out during the field’s first decade (Bloom, 1975; Zax & Spector). Both of these texts viewed Community Psychology as an outgrowth of the broader field of Clinical Psychology. Over time, the field would portray Community Psychology in a much broader context, deriving from many other sources in addition to Clinical Psychology such as sociology and public health. Other important publications of this first decade included Ryan’s Blaming the Victim (still, today, one of the most cited publications in the field) and Cowen’s Annual Review of Psychology chapter on social and community interventions. At the end of this decade, the Austin Conference was an opportunity to bring together the key figures in this field during the first 10 years and provide informal opportunities to examine the field’s conceptual independence from Clinical Psychology.

THE SECOND DECADE: 1975-1985

The late 1970s and early 1980s could be considered the “heyday” of Community Psychology. During this time period, the political climate made Community Psychology both relevant and necessary, and membership increased in the US in APA’s Division 27 (Community Psychology) (Toro, 2005, p.10).

The first Midwest Ecological Community Psychology Conference took place in 1978 at Michigan State University. This conference provided an opportunity for like-minded community psychologists and students to get together informally to discuss new developments, new training programs, and new research. This conference has now expanded beyond the Midwest to other regions of the US. These conferences have provided a new generation of community psychologists opportunities to put their theoretical ideas about collaboration, empowerment, and the creation of health-promoting settings into practice in their own environments. For a history of these conferences, see Flores, Jason, Adeoye, Evans, Brown, and Belyaev-Glantsman. Case Study 2.1 provides more information about students assuming a major role in the conference’s organization over time.

Case Study 2.1

Students Assume Leadership Roles at the Midwest Ecological Community Psychology Conference

Professors planned and organized the first few informal Midwest Ecological Community Psychology Conferences, but something very special happened in 1980 at the conference at Bowling Green State University. At the end of that meeting, several community psychologists were in a room discussing who would host next year’s event, when a graduate student in the room spoke up suggesting that because the conference was meant for graduate students, then the students should be planning and organizing it. Following this suggestion, students from the University of Illinois Chicago began the long-standing tradition of these conferences being student-run. The Midwest Ecological Community Psychology Conferences have kept going since then with student leadership. This informal support system has led to many networking opportunities over the years for faculty and students to get to know each other, and it has led to many job and training opportunities. As an example, at one of these meetings, Stephen Fawcett was invited to participate in a session to demonstrate how behavioral approaches could be integrated into the field of Community Psychology. Fawcett brought two of his graduate students, Yolanda Suarez-Balcazar and Fabricio Balcazar, and both had a chance to meet Chris Keys at the meeting. This contact eventually led to both graduate students finding their first jobs in Chicago. This is just one example of the networking that continues to lead to important professional and personal relationships among attendees of this student-run conference.

During this second decade, many community psychologists in the US became dissatisfied with the field of Community Psychology’s association as one of APA’s many divisions. There was a desire to bring more non-psychologists into the field. In addition, there were concerns about APA increasingly emphasizing clinical practice issues over all others. Also, there was a recognition that the term “psychology” no longer fit well with the work of many community psychologists. The group’s organizational name was then changed to the Society for Community Research and Action (SCRA), and the first Biennial Conference on Community Research and Action occurred in 1987. Though many community psychologists still remain members of APA and its Division 27, SCRA now has more non-APA members than ones who belong to APA; the Biennial has become the major national professional venue for Community Psychology.

Looking back on this second decade, this was a time of “soul searching” in the field of Community Psychology, the separation from APA and the initiation of the Biennial Conference both being signs of this. Another sign came from a string of “dueling addresses.” Different community psychologists were trying to strongly encourage the field to adopt one particular emphasis. In his Presidential address to the field of Community Psychology, Emory Cowen argued for prevention to become “front and center” in the field. A few years later, Julian Rappaport argued for an emphasis on empowerment rather than prevention. Ed Trickett argued for an emphasis on an ecological perspective in the field, as did James Kelly. Kelly’s ecological analysis sought to understand behavior in the context of individual, family, peer, and community influences. Prevention, empowerment, and the ecological perspective are three of the most important aspects of the world view that Community Psychology has adopted. We can embrace all the various perspectives in Community Psychology without dismissing those who have a perspective different from our own, in what might be called a “big tent” (Toro, 2005). A belief in the value of respect for diversity can apply to how we interact with our own colleagues in Community Psychology.

During this second decade, two new textbooks were published in 1977 by Heller and Monahan and Rappaport. Rappaport’s (1977) text, like his controversial Presidential address, presented a much more radical view of Community Psychology that emphasized the empowerment of the poor and otherwise disadvantaged, and a more active advocacy stance for community psychologists of the future.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, there was significant growth in the field of Community Psychology outside of the US and Canada. This growth included the first courses taught in Latin America (at the University of Puerto Rico; for more information see Montero) and in Australia (see Fisher), where the first professional organization of community psychologists outside of North America occurred in 1983. Since this time, some of the greatest growth in formal membership has occurred in Community Psychology organizations in areas of the world outside of North America (Toro, 2005).

THE THIRD DECADE: 1985-1995

In 1987, James Kelly edited a special issue of the American Journal of Community Psychology to commemorate the field which had just turned 20 years old (Kelly, 1987). Some of the 12 articles in the issue were brief reminiscences, while others were more substantive. Beth Shinn, for example, urged community psychologists to enter an even wider range of domains, including schools, work sites, religious organizations, voluntary associations, and government. Annette Rickel made an analogy to Erikson’s developmental stages in reviewing the status of our field at the time. She suggested that Community Psychology had progressed through adolescence and was entering early adulthood. Extending this analogy, the field is now over 50 years old, well into “middle age.” And, consistent with the sorts of issues that Erikson suggested might crop up during middle age, perhaps our field is concerned about its “long-term legacy.”

The “dueling addresses” mentioned above continued into the third decade. Annette Rickel in her 1986 Presidential address emphasized prevention, much like Cowen did in his address almost 10 years earlier. Beth Shinn in her 1992 Presidential address urged community psychologists to engage in new ways to cope with the social problem of homelessness. Irma Serrano-Garcia, based at the University of Puerto Rico, emphasized the need to empower the disenfranchised in her 1993 Presidential address. During this third decade, another new Community Psychology textbook was published (Levine & Perkins, 1987).

In 1988, there was a major conference in Chicago, IL trying to better define the theories and methods used by community psychologists (Tolan et al., 1990). Those in attendance discussed the role of theory in Community Psychology research. There was also an extended examination of the central and complex methodological issue of taking into account the ecological levels of analysis. Also addressed were issues of implementing their research, which for community psychologists is a matter of actualizing their values in working collaboratively with community partners.

THE FOURTH DECADE: 1995-2005

Starting in 1995, Sam Tsemberis (1999), a community psychologist from New York City, developed a program that has come to be called “Housing First.” The program, described in Chapter 1 (Jason et al., 2019), targets persons who are both homeless and living with a mental health condition. The intervention is a reaction to poorly researched transitional housing models that have rapidly become common in the US. Housing First combines up-front permanent housing with ongoing support services. In a few randomized trials, Housing First clients have become stably housed significantly quicker, and remained housed for significantly longer, than those in the control groups. Positive results have also recently been obtained in an evaluation of Housing First across five Canadian cities (Aubry et al., 2016). Housing First has also become very popular in Europe and in other developed nations. There is now an annual international conference to continue this work (Tsemberis, 2018).

More attention during this decade was provided to one of the key themes of the field: participatory approaches to research, which are characterized by the active participation of community members in the planning, implementation, and evaluation of research. Greater knowledge of this approach was essential for developing ways to collaborate with community members in order to define and intervene with the numerous social problems they faced. Due to this need, the 2nd Chicago Conference on Community Research was hosted at Loyola University in Chicago in June of 2002 (Jason et al., 2004), and it focused on the refinement of the theories and methodologies that can guide participatory research.

In 2004, SCRA, the main professional organization promoting Community Psychology in North America, gained solid financial security, perhaps for the first time in its history, by acquiring the American Journal of Community Psychology from its original owner, the international publisher Kluwer/Plenum.

THE FIFTH DECADE TO THE PRESENT

As another sign of the international growth of Community Psychology, in 2005 the European Community Psychology Association was formed. Prior to this development, Europeans had for many years a more informal “Network for Community Psychology.” The European Community Psychology Association has been operating an annual conference, held in different cities throughout Europe. As yet another sign of international growth, the first “International Conference on Community Psychology” was held in 2006 in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Held in even-numbered years, so as not to conflict with SCRA’s Biennial held in odd-numbered years, there have been International Conferences held in Portugal, Chile, Mexico, South Africa, and Uruguay. This international growth is very consistent with Community Psychology’s values emphasizing cultural diversity. Many community psychologists from around the world are actively collaborating with those in various nations around the world and an “internationalization” of the field is occurring in terms of practice, research, training, and theory (Reich et al., 2007).

In 2005, following the 40th anniversary of the founding of the field, a special issue on the history of Community Psychology was published in the Journal of Community Psychology (Fowler & Toro, 2008b). Articles in the special issue included a genealogical analysis of the influence of 10 key founders of the field (Fowler & Toro, 2008a), an account of “trailblazing” women in Community Psychology (Ayala-Alcantar et al., 2008), and documentation of the development of Community Psychology in different regions of the world.

Many community psychologists have made substantive contributions to the development of the field through their applied work, and have also impacted the development of the field through their teaching, mentorship, and conference presentations. Pokorny et al. (2009) tried to gauge the “influence” of community psychologists based on publications and citations to articles in the American Journal of Community Psychology and Journal of Community Psychology. Although many publications were by males from academic institutions, there were also publications from influential women, including Barbara Dohrenwend who contributed groundbreaking research dealing with a psychosocial stress model. She was also one of the original founders of the field of Community Psychology. Pokorny et al. did find that the number of women publishing articles has increased over time, as is evident in Case Study 2.2.

Case Study 2.2

Publications of Women in the Field

In 1970, around the time of the founding of the field of Community Psychology, women comprised approximately 20% of Ph.D. recipients in psychology. By 2005, nearly 72% of new psychology doctoral students were women. In many ways, articles published in journals are records of changing times as they illustrate how marginalized groups, like women, have transitioned to greater prominence. Patka, Jason, DiGangi, and Pokorny in 2010 found that in the early 1970s, women represented less than 12% of publishing authors in the two major Community Psychology journals, but by 2008, the number of women publishing in the two journals had increased to 61%. The findings from this study highlight the evolving role of women in the field of Community Psychology.

Community Psychology continued to make advances during this period in attempting to better understand social change in a world that is both complicated and often unpredictable. This field has increasingly worked to take into consideration dynamic feedback loops, which need to transcend simplistic linear cause and effect methods. In other words, the theories and methods of the field of Community Psychology are increasingly trying to capture a systems perspective, or the mutual interdependencies that Kelly’s ecological model has pointed to, regarding how people adapt to and become effective in diverse social environments.

New methods during the past 15 years have helped community psychologists conceptualize and empirically describe these dynamics, with quantitative and qualitative research methods that support contextually and theoretically-grounded community interventions (Jason & Glenwick, 2016). More attention is being directed to mixing qualitative and quantitative research methods in order to provide a deeper exploration of contextual factors. More sophisticated statistical methods help community psychologists address questions of importance as they work to describe the dynamics of complex systems that have the potential to transform our communities in fresh and innovative ways.

Finally, this free online textbook that you are reading, like the earlier development of the Ecological Community Psychology Conferences, is an illustration of how community psychologists put the field’s principles and theories into practice. Community psychologists believe that “giving psychology away” is the best course of action for an organization committed to prevention, social change, social justice, and empowerment.

AN HISTORICAL UPDATE

Since 2019, a lot has happened in the world. Many of the recent events have direct or indirect relevance to the activities of community psychologists. In addition to major wars that have developed in the Ukraine, Gaza, and Sudan, we continue to have various protests around the country associated with the Black Lives Matter (BLM) and the Me Too Movements. These movements have attempted to expose and eliminate discrimination against African-Americans and other racial and marginalized groups and to expose and eliminate sexual abuse and harassment against women. The BLM Movement developed in response to high-profile cases of bias and violence by police against people of color. Many of these cases led to the death of African-Americans at the hands of (mostly white) police. The Me Too Movement grew out of the cases brought by a number of high-profile women, many in the entertainment industry. Many community psychologists have participated in the various protests inspired by these Movements as well as protests against the ongoing wars.

The COVID-19 pandemic, which began in March 2020, has had an impact on most Americans and those in many other nations around the world. Like everyone else, community psychologists, in the early months of the pandemic, wore masks in public places to avoid infection and were motivated to get the vaccines that, luckily, were being tested at breakneck speed due to recent scientific advances in vaccine development. Community psychologists engaged in community-based research involving face-to-face data collection often had to suspend their research projects for up to two years to maintain safety from infection among both the researchers and community participants (e.g., Cannoy, 2023).

Beginning immediately after his inauguration in January 2025, President Donald Trump has issued a record number of Executive Orders on a wide range of topics advancing Trump’s brand of conservative political values. These Orders include ones that prohibit universities from promoting Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) efforts. Such efforts are widely supported by community psychologists. Some universities, like Harvard, have refused to comply with these Orders, resulting in the government suspending all federal funding for research and other legitimate DEI-related activities. While there are court actions against many of the Orders, which may render them unconstitutional, the Orders have had a clear chilling effect on many engaged in DEI-relevant work.

SUMMING UP

This chapter has reviewed the last 60 years in which the field of Community Psychology has developed after its start in 1965 at the Swampscott Conference. With a focus on prevention, ecology, and social justice, the field has offered society new ways of thinking about how we might best solve our social and community problems. The chapter has documented key events that have occurred, including organization changes, key publications and conferences, and international developments. The field has had some “growing pains,” but now appears to be well-established and mature.

Critical Thought Questions

- Do you think that the field of Psychology, in general, could use the ideas of Community Psychology to change the way they approach solving mental health problems?

- How can prevention be used to solve some of the problems for people who are homeless or addicted to drugs?

- The early pioneers of the field of Community Psychology were challenging the way that psychologists were delivering services to others. Can you think of a particular mental health problem that this might apply to?

- If you were to make an argument to some friends about the advantages of a more community-oriented approach, what might you say to help convince them of the benefits of this alternative way of thinking about social issues?

Take the Chapter 2 Quiz

View the Chapter 2 Lecture Slides

____________________________________________________________________

REFERENCES

Aubry, T., Goering, P., Veldhuizen, S., Adair, C. E., Bourque, J., Distasio, J., Latimer E, Stergiopoulos V, Somers J, Streiner D.L., & Tsemberis, S. (2016). A multiple-city RCT of Housing First with Assertive Community Treatment for homeless Canadians with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 67(3), 275-281.

Ayala-Alcantar, C., Dello Stritto, E., & Guzman, B. L. (2008). Women in community psychology: The trailblazer story. Journal of Community Psychology, 36, 587-608.

Bennett, C. C., Anderson, L. S., Cooper, S., Hassol, L., Klein, D. C., & Rosenblum, G. (1966). Community psychology: A report of the Boston Conference on the Education of Psychologists for Community Mental Health. Boston University Press.

Bloom, B. L. (1975). Community mental health: A general introduction. Brooks/Cole.

Cannoy, C. (2023). Homelessness in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: An assessment of changes in needs and characteristics. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Department of Psychology, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI.

Cowen, E. L., Trost, M. A., Izzo, L. D., Lorion, R. P., Dorr, D., & Isaacson, R. V. (1975). New ways in school mental health: Early detection and prevention of school maladaptation. Human Sciences Press.

Fairweather, G. W., Sanders, D. H., Maynard, H., & Cressler, D. L. (1969). Community life for the mentally ill. Aldine.

Fowler, P. J., & Toro, P. A. (2008a). Personal lineages and the development of community psychology: 1965 to 2005. Journal of Community Psychology, 36, 626-648.

Fowler, P. J., & Toro, P. A. (2008b). The many histories of community psychology: Analyses of current trends and future prospects. Journal of Community Psychology, 36, 569-571.

Jason, L. A., Glantsman, O., O’Brien, J. F., & Ramian, K. N. (2019). Introduction to the field of Community Psychology. In L. A. Jason, O. Glantsman, J. F. O’Brien, & K. N. Ramian (Eds.), Introduction to Community Psychology: Becoming an agent of change. https://press.rebus.community/introductiontocommunitypsychology/chapter/intro- to- community-psychology/

Jason, L. A., & Glenwick, D. S. (Eds.). (2016). Handbook of methodological approaches to community-based research: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods. Oxford University Press.

Jason, L. A., Keys, C. B., Suarez-Balcazar, Y., Taylor, R. R., Davis, M., Durlak, J., & Isenberg, D. (Eds.). (2004). Participatory Community Research: Theories and methods in action. American Psychological Association.

Kelly, J. G. (1966). Ecological constraints on mental health services. American Psychologist, 21, 535-539.

Kelly, J. G. (1987). Swampscott anniversary symposium: Reflections and recommendations on the 20th anniversary of Swampscott. American Journal of Community Psychology, 15(5).

Kloos, B., Hill, J., Thomas, E., Wandersman, A., Elias, M. J., & Dalton, J. H. (2012). Community psychology: Linking individuals and communities. Wadsworth.

Levine, M., & Perkins, D. V. (1987). Principles of Community Psychology: Perspectives and applications. Oxford University Press.

Moritsugu, J., Duffy, K., Vera, E., & Wong, F. (2019). Community Psychology (6th ed). Routledge.

Patka, M., Jason, L.A., DiGangi, J., & Pokorny, S.B. (2010). The academic contributions of women in Community Psychology. The Community Psychologist, 43(2), 6-8.

Pokorny, S. B., Adams, M., Jason, L. A., Patka, M., Cowman, S., & Topliff, A. (2009). Frequency and citations of published authors in two community psychology journals. Journal of Community Psychology, 37, 281-291.

Rappaport, J. (1977). Community psychology: Values, research, and action. Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

Reich, S., Riemer, M., Prilleltensky, I., & Montero, M. (Eds.). (2007). International Community Psychology. History and theories. Springer.

Tolan, P., Keys, C., Chertok, F., & Jason, L. A. (Eds.). (1990). Researching Community Psychology: Issues of theories and methods. American Psychological Association.

Toro, P. A. (2005). Community psychology: Where do we go from here? American Journal of Community Psychology, 35, 9-16.

Tsemberis, S. (1999). From streets to homes: An innovative approach to supported housing for homeless adults with psychiatric disabilities. Journal of Community Psychology, 27, 225-241.

Tsemberis, S. (June, 2018). Housing First: Why person centered care matters? Third International Housing First Conference, Padua, Italy.

The long-term process of reducing the number of psychiatric hospitals and replacing them with less isolatory and community-based alternatives for people with disabilities or mental illnesses.

A national movement in the 1960s to more efficiently and cost-effectively treat mental illness in community settings rather than solely in psychiatric hospitals.

The 1965 inaugural conference in Swampscott, Massachusetts that led to the creation of the field of Community Psychology.

A type of doctoral program that provides students both clinical training, such as psychopathology, therapy, and assessment, as well as Community Psychology skills, such as consultation, evaluation, and community intervention.

A subfield of psychology related to Community Psychology which focuses on the real-world relationships between people and their environments.

Understanding the relationships between people and their social environments (e.g., families, groups, communities, and societies).

An annual Community Psychology conference organized and led by students in the Midwest. Other regional conferences include the Southeast, Northeast, and Eastern ECO conferences, as well as the Community Research and Action in the West Conference.

A conference held every two years by The Society for Community Research and Action.

The focus on actions that stop problems before they happen by boosting individual skills as well as by engaging in environmental change.

The process of gaining power emerging at the individual, organizational, community, and societal levels, which are affected by peoples' previous experiences, skills, actions, and context.

Acknowledgment, acceptance, and respect for the full range of human characteristics in their social, historical, and cultural contexts.

The relationship between thought and behavior, and social factors.

A consideration of individual, group, community, and ecological contextual factors when examining a phenomenon of interest.

The interrelated relationships between the factors in the ecological model and how they influence people adapting to their environments.

The individual, psychological, familial, community, and societal factors that influence people.