11 Community Interventions

Isidro Maya-Jariego and Daniel Holgado

Chapter Eleven Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Differentiate professionally-led versus grassroots interventions

- Understand what it means for a community intervention to be effective

- Know why a community needs to be ready for an intervention

- Be aware of the steps to implementing community interventions

Many older people live alone, as is the case with Antonia. Since her husband died, Antonia has been living on her own in a small apartment in the Triana neighborhood in Seville, Spain. Due to problems with her mobility, she barely leaves her home and needs help to clean her house and make food. She misses having company over to chat and hang out with. She is also afraid of falling or having an accident and is worried there is no one who can help her. A neighbor told Antonia that the University of Seville now offers a service where a student from outside the city can live with her during the academic year, in exchange for housing. Antonia decided to join this special Community Psychology oriented program and was very happy that the student could help her with household chores and accompany her on a day-to-day basis.

The Community Service of the University of Seville in Spain has developed this community intervention program that matches university students with those who need services, including the elderly, people with disabilities, and single mothers. With this program, students receive free housing in exchange for providing company to the people with whom they live. They are also expected to help out with small domestic tasks and provide assistance to their hosts. The program is based on models of social support and mutual help. The university helps by matching students with those who need these resources, but also provides training, guidance, and ongoing monitoring to ensure that both parties benefit from the program. By being involved in this exchange, the students develop empathy, caring skills, and communication competencies, all attributes necessary to build strong communities. The evaluation of the program has shown improved perceptions of available social support and improved psychological well-being among participants. This program is an example of a successful community intervention.

In general terms, community interventions refer to actions that address social problems or unmet human needs, and take place in a neighborhood, community, or other setting. A community intervention is, therefore, an intentional action to promote change that can be expressed in different ways depending on the needs of the community. One type of program is a more traditional type known as a professionally-led intervention; it involves a program planned and implemented by professionals. For example, a mental health practitioner could have visited Antonia in the example above and provided her medications to relieve her depression. A second type of intervention aligns more with the spirit of Community Psychology, in that it uses approaches of both participation and collaboration, called a grassroots intervention. This second type of community intervention involves bringing volunteers into the homes of people like Antonia, and working together to develop and provide the social support intervention. These types of programs often have recurring themes of prevention, social justice, and an ecological understanding of people within their environments that were described in Chapter 1 (Jason et al., 2019). Below we will describe in more detail the methods utilized during the development and implementation phases of both traditional and participatory community interventions.

The first of the two types of interventions involves developing and implementing a program in a more traditional style, with a mental health professional designing and implementing the intervention. For example, a psychologist can teach a group of teenagers positive social skills so that they can confidently and voluntarily say “no” to their peers when they are encouraged to consume alcohol or other substances. A second type of intervention involves a participatory approach. For example, imagine security problems are affecting your neighborhood, and you meet with a group of neighbors to address how this issue is impacting your community. Instead of implementing preconceived and predesigned activities (e.g., the educational materials in the traditional example above), everything is decided in collaboration with the neighbors through active citizen participation. The intervention emerges as neighbors establish objectives (i.e., what problems they want to solve in the neighborhood) and decide what actions they can carry out together. The case study below shows how important citizen participation is for solving community problems.

Case Study 11.1

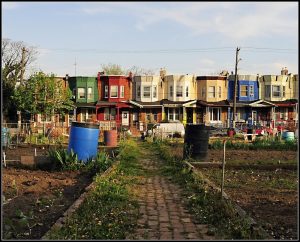

The Rochelambert Lot and Grassroots Organizing

A grassroots movement of residents in Rochelambert, a neighborhood of Seville, formed when the city council and a company announced the construction of a private parking lot in their community. One of the neighborhood leaders explained: “Here we have 300 parking lots on the surface and the neighbors did not see the need to build a parking lot. The town hall and a promoter decided to build an underground car park, together with a building, without consulting the neighbors. We did not see the need, because, in the end, we would pay for a parking space in a place where we already had parking. So we organized ourselves. With the participation of the community presidents in each block we coordinated; each neighbor began to pay one euro per month for the expenses of posters, travel and lawyers; as we thought that the cranes would come at dawn, we made patrols during the night … The press echoed and we were clear that this battle was going to be won, that things are not imposed … I think it was important to have people in the neighborhood who had experienced the transition from dictatorship to democracy and knew the importance of political participation. The fight lasted five months, and in the end we managed to stop the parking lot. Since then we maintain friendship, because that united us a lot.”

These types of bottom-up activities or grassroots movements are going on all the time, and it is our challenge to identify and work with these groups to promote behavioral change in defined community contexts so that social problems can be addressed. Community Psychology emphasizes the importance of community participation as a key process that improves preparation for change, contributes to community organization, and facilitates the implementation of collective actions, as the next case study below also illustrates.

Case Study 11.2

Participatory Research with Fishing Communities

The mouth of the Guadalquivir River is part of a “hotspot of biodiversity” in southern Europe, where fishermen make their livelihood. As there were certain areas of the river that were being overfished, there was a need to address this problem. In a study with fishermen in the area, we analyzed the social networks that connect them, exchanging social support and information about the marine environment (Maya-Jariego et al., 2016). In a later meeting, the fishing communities decided, in a participatory way, on a series of actions that they would carry out in order to conserve the fishing resources of the area. The information on the networks among the fishing community served to reflect on the preferred fishing areas of different groups of participants in the fishing community. Having an overview of the area allowed them to detect the fishing grounds that were being over-exploited so that they could self-regulate fishing practices.

In this case study, the involvement of fishing communities in the management of fisheries was essential for the effective implementation of quota policies as well as restrictions on permitted types of fishing. More information on these types of participatory approaches is available at Research for Organizing, which shows you how to use very practical toolkits for developing action efforts to solve community problems.

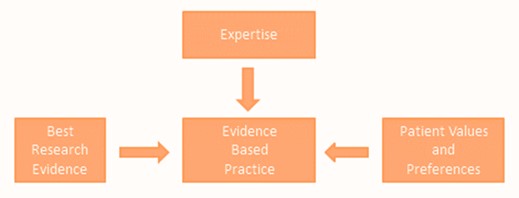

In the next section, we will show the importance of designing effective programs, or programs that actually work. Programs that are designed to work effectively are called “evidence-based,” meaning that prior research has shown that these programs are successful in what they are intended to do. Another essential feature of community interventions is that they are implemented interventions to meet the needs and interests of the community. We will show how the outcomes of the intervention depend, in part, on the degree of readiness for change in the community. A high degree of readiness means that the community members are generally excited about the intervention and committed to seeing the program through. Finally, community interventions are implemented successfully when the community psychologists have the necessary skills and abilities to work collaboratively with community members to make effective, long-lasting changes.

EFFECTIVENESS

The logic of effectiveness is strongly rooted in the tradition of Kurt Lewin’s (1946) action research. His work involved improving intergroup relations and preventing discrimination, and it helped us understand the importance of using solid research methods and outcome studies to support our work. The key for improving effectiveness is to base programs on previous research evidence and to apply strategies of further research to support the effectiveness of the program. The sequence of planning—action—fact-finding is a learning cycle based on experience. In the first step, the theory guides our action. In the second step, we then implement the intervention. In the third and last step, evaluative research is used to check the effects of the action. However, the intervention does not end there because the results can change the way we think about how we might develop even more effective interventions to solve problems in the future. Community psychologists constantly repeat these three steps to gain more data to improve the effectiveness of their interventions.

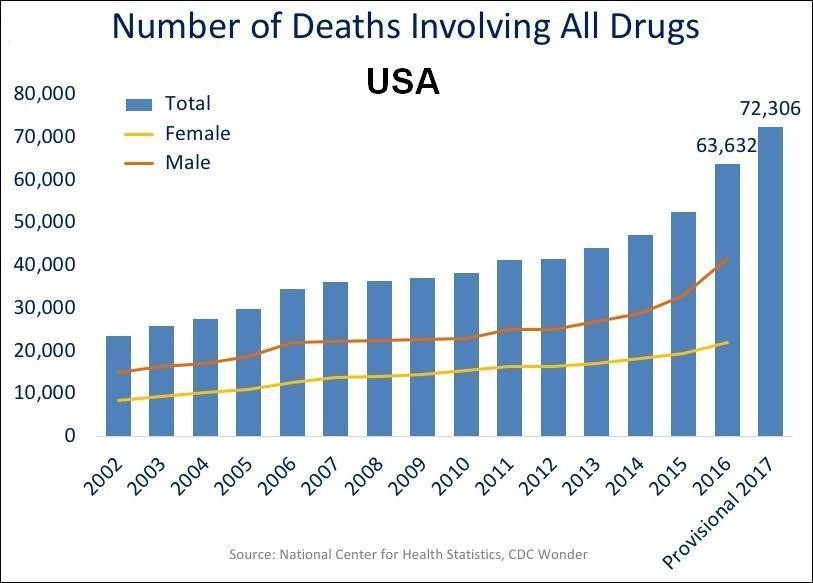

Let’s look at this approach with a specific case. The prevention of drug abuse is important, as thousands of people die each year from addiction. Research has shown that the majority of adults with drug abuse problems start using when they are teenagers, are subject to social peer pressure, and are exposed to negative behavior models in their immediate family and community environment. In addition, a growing number of studies over decades showed that specific programs are effective in overcoming these issues (Griffin & Botvin, 2010), and the results of one program led to even more effective and comprehensive programs. These types of prevention programs have multiple components including providing skills to resist attempts at social influence, improving communication in the family, and reducing adolescents’ access to drugs. Prevention programs at school have provided youths training in social skills to resist peer pressure, raise self-esteem, and reduce favorable perceptions about substance use. In addition, interventions with parents aimed to improve family communication and the establishment of rules against using drugs. Finally, community prevention efforts have confronted larger scale ecological factors, such as the media that often promote alcohol, tobacco, or illegal substance use. In this case, it is important for an intervention to use many of these strategies together, with comprehensive actions being developed through community coalitions. The following case study is an example of community psychologists working on multiple ecological levels when implementing a prevention program.

Case Study 11.3

A Community Intervention to Decrease Adolescent Tobacco Use

Kaufman et al. (1994) launched a community intervention to decrease the number of new smokers, particularly focusing on African American adolescents. The preventive intervention combined a school-based curriculum with a media campaign. A total of 472 elementary schools provided students with a smoking prevention booklet, while the media campaign reached out to the broader community. A widely distributed local newspaper included parts of the curriculum on its weekly children’s page. A local radio station, with over a million listeners, aired a call-in talk show focusing on better parent-child communication about smoking. The station also aired anti-smoking public service announcements and promoted a smoking prevention rap contest for school children. Winners from five age groups had their raps aired, and the overall winner was a guest DJ. Additionally, owners of approximately two hundred billboards sponsored a contest in which children developed posters conveying anti-smoking messages, and winning posters from each of the five age groups were displayed on billboards. Participants for this preventive trial were randomly assigned to groups that either received the school-based curriculum or did not. However, both groups were exposed to the media messages and over 90% of the students indicated that they listened to the radio program on a regular basis. Smoking significantly decreased over time for students in both groups. But only those students provided with the school curriculum plus media campaign reported reading significantly more of the newspaper content and substantially increased their knowledge about the dangers of smoking, compared to the student group only exposed to the media campaign.

In the case study above, the intervention effects demonstrated the merit of community-wide, comprehensive preventive interventions. As demonstrated, Community Psychology interventions are based on the scientific understanding of the problem (e.g., drug abuse), with an empirical analysis of risk and protective factors. Secondly, the interventions keep in mind the changes that need to be achieved in the community, aiming to consider the ecological levels that were discussed in Chapter 1. As indicated earlier, these interventions also bring in the active participation of community members in planning and implementing the programs.

IMPLEMENTATION

What do we mean by implementation? As mentioned above, having a good community intervention depends on how well the program has been designed and tested out to be effective. It is also important to keep in mind how ready or interested the setting or people are in the intervention because if the community does not really want the program, it is very unlikely to be accepted or used by the community members.

Case Study 11.4

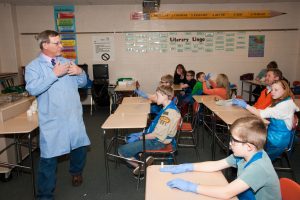

A Classroom Exercise and Lessons in Implementation

One high school teacher performed an interesting exercise with his students in a class. First, he inserted cotton in a transparent bottle. Next, he lit a cigarette and placed it so the smoke entered the bottle. After a while, the students could see that the cotton had blackened and retained a part of the tar and other harmful elements of tobacco. In a simple way, this showed the effect of smoking on the lungs. When adolescents are informed about the negative health consequences of smoking, they may be less likely to use tobacco. However, the achievement of good preventive results with this group of adolescents does not only depend on having clear intervention ideas, such as the demonstration of the cotton in the bottle but also enlists the help of the students and teachers in changing the social pressures to smoke. It also involves the larger community including the media, such as in Case Study 11.3. Furthermore, it is important to have the groups actively invested in the program, and this can occur when they participate in the design and implementation of the intervention. In part, the success of the intervention also depends on when and where this activity will occur during and after school; these type of factors influence how well the program is implemented.

In Case Study 11.4, we are focusing on community dynamics—a critical factor that is often forgotten when interventions are developed. By considering the community dynamics when implementing an intervention, this helps shape whether the intervention should be more traditional, with an expert delivering a packaged prevention program, or more in line with the spirit of Community Psychology, where community partnerships actively bring those voices into the design of the intervention.

Theory is an important aspect when community psychologists develop and implement ecological community interventions, but there is more that is needed to make long-lasting changes. Other critical areas involve the skill levels and knowledge of those who implement the programs, the interest and readiness for the intervention among the community members, and the availability of the needed resources required by the intervention. We can illustrate these points with the example of smoking, which was reviewed in Chapter 1. If you can believe it, there was a time when commercials had physicians endorsing tobacco use (see the video on physicians endorsing tobacco in Chapter 6; Stevens & Dropkin, 2019)! In the 1940s and 1950s, few people thought that tobacco use was harmful. It was not until tobacco use and its effects were studied for years that public perception, and then policy, were changed. Over the past 50 years, there have been significant reductions in smoking in the US (Biglan & Taylor, 2000). This reduction was due to evidence gathered over time on the consequences of tobacco abuse, which helped change people’s opinions about smoking.

Communities may vary in the degree of awareness of a specific social problem, as few were willing to address tobacco use as a problem before the 1960s. With the Surgeon General’s report, the public began to view tobacco as a harmful social problem. This shows that, in practice, some communities may be more or less prepared for changes. That is why the degree of “community readiness” often determines whether our community interventions will be effective. From this perspective, implementation is a key process: since it is not enough to design effective programs, it is also necessary to attend to the factors that make the desired social change possible.

Case Study 11.5

The Importance of Public Awareness in Prevention Efforts

Investigators have tried to prevent intimate partner violence in different Latin American countries. In one of the countries, there was frequent debate on television about gender-based violence, and this led to several organizations advocating for greater protection of women. In another country, there was little publicity or awareness of these types of issues, and there was not the same type of organizational advocacy. In other words, the issue was not publicly discussed nor were there organizations promoting community awareness of this topic.

In the above case study, the level of community readiness was high in the first country but low in the second, which led to more intimate violence prevention programs being launched in one country than the other.

Let’s go back to the above cases 11.3 and 11.4 showing tobacco prevention to again illustrate the importance of community readiness and successful implementation. The “Communities That Care” program well represents this concern for awareness of community contexts and the implementation process (Oesterle et al., 2015). This is a Community Psychology program that aims to reduce drug dependency, criminal behavior, violence, and other harmful behaviors among adolescents. The program is often initiated through a local community coalition, in which different organizations collaborate to develop united action for preventive purposes. This means that adolescents receive a consistent message from different agents of the community and are exposed to social norms that promote healthy habits. In addition, these community agents participate in choosing the evidence-based practices that will be implemented. Accordingly, they are jointly responsible for both the actions that are carried out and the introduction of adjustments to adapt them to the specific characteristics of the community. Finally, it is important that preventive actions have the intensity, continuity, and dose necessary to have the most significant impact in the community context. Dose refers to the number of sessions or the duration of a program and influences the level of results we can achieve. For example, we cannot expect one social skills training session to have the same result as a semester-long program. Just like a muscle, the more these programs are exercised, the stronger they are. Thus, beyond the quality of the programs, how the community supports the idea and helps to carry it out affects how the program is applied on multiple levels in the community. The application of the Communities That Care program in neighborhoods has been found to reduce the overall consumption of alcohol, cigarette, and smokeless tobacco, as well as delinquent behavior. This video link provides more information about the Communities That Care model and its effectiveness.

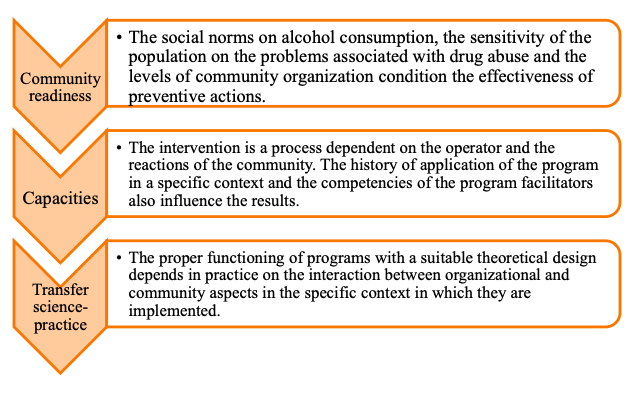

In Figure 3, we have summarized some of the key factors in the implementation process when trying to prevent alcohol abuse.

TRANSFORMING COMMUNITY CONTEXTS

When we seek to address problems through community interventions, we discover the importance of the environment and potential community partners (Shinn & Toohey, 2003). In other words, we need to understand the context, or the neighborhoods and community settings, within which we place the community interventions. We can illustrate this with the following examples involving refugees and the approaches of several countries in dealing with this issue.

In Colombia, displaced persons can access housing when they flee political violence. However, this often places them in a segregated space where they share their day-to-day lives with other people who also suffer from post-traumatic stress. This also occurs in Spain with incoming refugees, who are received in publicly owned “reception centers” that cover their basic housing, food, and health needs. They can also access language courses, workshops to improve employability, and other programs that aim to ease their integration into a new country. However, only a small percentage of the residents in the reception centers are actually able to find work in Spain. Consequently, refugees have not been able to take advantage of the provided psychosocial resources. The case study below illustrates what needs to be taken into consideration when designing effective community interventions.

Case Study 11.6

The Importance of an Ecological Lens: A Family Seeking Asylum

The Patatanian family arrived in Madrid from Armenia, fleeing the harassment they suffered for religious reasons. They were received in the center of asylum seekers and provided accommodation and food. The parents received Spanish classes and made some contacts to learn about the labor market in Madrid while waiting for their case to resolve. Their children joined a school and, despite some difficulties adapting to a new country, made friends and did well enough academically. However, after nine months in Spain, they received a notification that the government did not recognize their refugee status. Consequently, although the Spanish teaching and employment guidance programs were well designed, the legal situation prevented the integration of the Patatanian family in Spain by not providing them the ability to apply for jobs. This resulted in the programs not achieving the objectives they were designed to meet.

The family, however, was fortunate to have another chance for a better life. Shortly after their experience in Spain, they decided to try again in Canada, where they were welcomed with not only the classes and resources but also the opportunities to fully participate in the workforce. The family members learned French and integrated very well with the community of Armenians living in Montreal. They also became friends with some neighbors and, little by little, could normalize their lives and find employment.

The case study of the family above shows why community interventions often need to transcend the individual level and deal with higher ecological levels. That is, it is about introducing deeper, second-order changes such as providing employment opportunities, that can have a more lasting and sustainable effect on individual behavior.

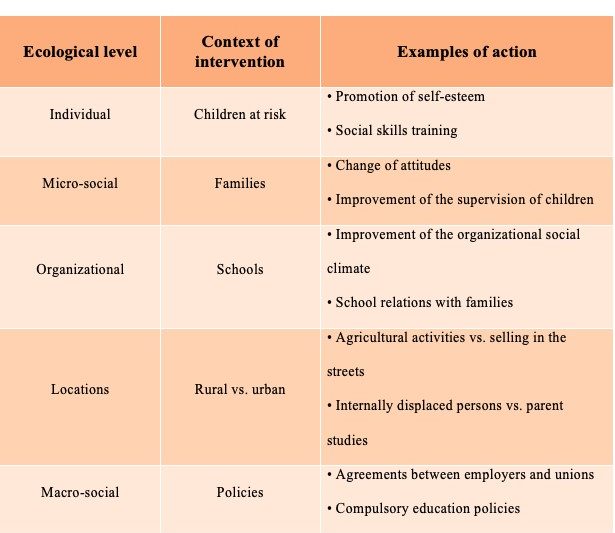

Let’s take child labor as another example. Child labor is a worldwide problem, affecting a large number of developing countries. It has a very negative impact on the cognitive, affective, and social development of the child. Programs can be developed that promote self-esteem, train social skills, or reinforce academic motivation. But, an effective intervention program also needs to focus on the children’s environment. If parents need to have their children work at very young ages to support the family as a whole, community psychologists need to take this into consideration and possibly find better ways for the parents to earn money so that they do not need to depend on their children to earn money, as illustrated in the case study below.

Case Study 11.7

Edúcame Primero

The Edúcame Primero is an initiative that aims to reduce child labor through psychoeducational strategies and community collaboration. Some of the strategies are oriented toward creating safe learning spaces in the school and the involvement of the family in the education of the children, as well as the collaboration with other agents in the community context. A central element of the program is the use of a methodology called Spaces for Growth (SfG): that is, complementary training workshops for formal education that include strategies for facilitating participation and active collaboration for children and young people, as well as their families and the staffs of educational centers. The SfG promote collaboration with different agents in educational and community contexts, namely: teachers, professionals, community leaders, and families. They participate in the design of the workshops, the configuration of the program content, and the adaptation of the program to the characteristics of the educational center. To this end, the involvement of parents, exchange forums with community agents, and regular meetings with staff of the educational centers are organized. Community readiness is evaluated by gathering information on (a) existing resources and key players in the community context, (b) previous experience in the implementation of intervention programs in child labor, (c) the level of awareness about child labor as a problem among community members and (d) the degree of community cohesion around existing needs linked to child labor. Finally, facilitators play a key role in the adjustment to the community context. They are professionals selected on the basis of their capacity for teaching children and young people, their knowledge of the community environments in which the SfG will be implemented, as well as their leadership skills (e. g., abilities for community mobilization). The Edúcame Primero program has proven to be a good practice in the prevention of child labor, with positive results in terms of prevention and reduction of child labor. A video of the Edúcame Primero is available here.

In Latin America, these types of intervention efforts have been developed by international organizations, such as the International Labor Organization (through the International Program on the Elimination of Child Labor), in collaboration with national governments and other third-party entities. In the last two decades, these international organizations have designed and implemented programs that have resulted in the worldwide prevalence of child labor decreasing by about 30 percent. As we can see in the Edúcame Primero example, environmental contexts need to be considered when developing these types of Community Psychology interventions. Figure 4 illustrates the multiple ecological levels of community-based interventions.

SUMMING UP

There are many important lessons we can learn from working to develop community interventions. Some of these lessons include the need for using programs that have some evidence that supports them and working collaboratively with the community to be sure that they support and help design the actual program. Community psychologists use good theory and methods with the community members, and this is something that often does not occur with many interventions that are thrust on communities with little input from community members. Active community participation makes it more likely that the intervention is accepted and carried on into the future by the community members.

In summary, community intervention is a planned action aimed at changing behavior in relation to a social problem. Action research consists of a learning cycle based on experience, through which interventions are based on previous theoretical models and in turn, generate new knowledge through the application of programs. Effectiveness is gauged by aiming at obtaining results with the application of evidence-based practices. Implementation should take into consideration the level of community readiness and focus on promoting active community participation.

Critical Thought Questions

- You probably know of a community program because you have been a participant, volunteer, or simply an observer of it. Can you explain the difference between planning and implementation of programs, using this example?

- Explain the following sentence: “to make good planning it is important to know the previous research on the subject, to make a good implementation it is important to have a good knowledge of the community receiving the intervention.”

- Think of a social problem that is relevant to you and reflect on the degree of “community readiness” that exists in your city to deal with this problem. Justify your arguments with some empirical data referring to the place where you reside.

- Using the “Edúcame Primero” program as an example, try to explain the following concepts: “effectiveness”, “dose”, and “community coalition”.

Take the Chapter 11 Quiz

View the Chapter 11 Lecture Slides

____________________________________________________________________________

REFERENCES

Biglan, A., & Taylor, T. K. (2000). Why have we been more successful in reducing tobacco use than violent crime? American Journal of Community Psychology, 28, 269-302.

Griffin, K. W., & Botvin, G. J. (2010). Evidence-based interventions for preventing substance use disorders in adolescents. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics, 19, 505-526.

Jason, L. A., Glantsman, O., O’Brien, J. F., & Ramian, K. N. (2019). Introduction to the field of Community Psychology. In L. A. Jason, O. Glantsman, J. F. O’Brien, & K. N. Ramian (Eds.), Introduction to Community Psychology: Becoming an agent of change. https://press.rebus.community/introductiontocommunitypsychology/chapter/intro-to-community-psychology/

Kaufman, J. S., Jason, L. A., Sawlski, L. M., & Halpert, J. A. (1994). A comprehensive multi-media program to prevent smoking among black students. Journal of Drug Education, 24, 95-108.

Lewin, K. (1946). Action research and minority problems. Journal of Social Issues, 2(4), 34-46.

Maya-Jariego, I., Florido, D., Holgado, D., & Hernández, J. (2016). Network analysis and stakeholder analysis in mixed methods research. In L. A. Jason & D.S. Glenwick (Eds.), Handbook of methodological approaches to community-based research: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods, (pp. 325-334). Oxford University Press.

Oesterle, S., Hawkins, J. D., Kuklinski, M. R., Fagan, A. A., Fleming, C., Rhew, I. C., Brown, E.C., Abbott, R.D., & Catalano, R. F. (2015). Effects of Communities That Care on males’ and females’ drug use and delinquency 9 years after baseline in a community-randomized trial. American Journal of Community Psychology, 56, 217-228.

Shinn, M., & Toohey, S. M. (2003). Community contexts of human welfare. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 427-459.

Stevens, E., & Dropkin, M. (2019). Research methods. In L. A. Jason, O. Glantsman, J. F. O’Brien, & K. N. Ramian (Eds.), Introduction to Community Psychology: Becoming an agent of change. https://press.rebus.community/introductiontocommunitypsychology/chapter/community-research/

The use of different research methods to understand person-environment interactions and also determine whether community interventions have been successful.

Prevention or promotion programs that aim to promote behavioral change in defined community contexts to address social problems.

A field that goes beyond an individual focus and integrates social, cultural, economic, political, environmental, and international influences to promote positive change, health, and empowerment at individual and systemic levels (SCRA27.org).

The focus on actions that stop problems before they happen by boosting individual skills as well as by engaging in environmental change.

Involves the fair distribution of wealth, opportunities, and privileges that provide equal opportunities for education, healthcare, work, and housing.

Understanding the relationships between people and their social environments (e.g., families, groups, communities, and societies).

Assures a higher level of involvement in partnerships involving both community psychologists and community members.

Individuals at the ground level of a community group or an organization are brought into key roles in intervention design and planning.

An approach to intervention based on research that systematically demonstrates its effectiveness.

Achievement of the results intended by the intervention (it is an indicator that the intervention works properly).

A set of organizations, institutions and community agents that cooperate to improve the living conditions of the community.

The research whose results fall strictly on observable and verifiable evidence. It can be based on quantitative or qualitative methods.

Sequence of actions that goes from the planned on paper to actions in natural community contexts. Good implementation depends on the skills of the community psychologists involved and the degree of community readiness.

Degree to which the community is prepared for the behavioral and social changes that are intended by the intervention.

Refers to how much of the intervention they do deliver: for example, number of sessions, number of hours, time of application of the program, and so on.

Involves initiating more structural, long term, and sustainable transformational changes.