7 Chapter 7: Zoonotic Infections

Brandye Nobiling

Chapter Objectives:

- Identify risk factors for tick-borne infections.

- Identify and describe selected bacterial, viral, and parasitic zoonotic infections.

- Discuss prevention measures for selected zoonotic infections.

- Discuss how public health policy has impacted national and global rabies cases.

- Discuss how vultures act as public health heroes.

INTROduction

Zoonotic infections, also called zoonoses, are infections that are transmitted from non-human animals to humans. They are very common globally, accounting for many new cases of infection in humans. In some cases, like HIV, an infection can start as a zoonoses then mutate to become only transmissible human to human. This chapter covers some of the most prevalent zoonotic infections based on data from the WHO and CDC. CDC identifies 8 of concern here.

Bacterial infections caused by ticks

Ticks are a constant source of zoonotic infections. Some of the most common zoonoses caused by ticks are bacterial infections, such as Lyme disease, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, and Ehrlichiosis.

Lyme Disease

Lyme disease is the most commonly reported disease caused by ticks in the United States (CDC, 2021). Lyme disease is caused by a bite from the blacklegged tick, also known as the deer tick. Lyme disease has been identified by the CDC as one of the 8 zoonotic infections of concern. According to the CDC (2021), there were nearly 35,000 total cases of confirmed and probable cases of Lyme disease in 2019. The below image shows blacklegged ticks at the larva, nymph, and adult stages, from left to right. They are the most likely to transmit Lyme disease in the nymph stage.

Individuals at risk

- Location: Lyme disease was first identified in Lyme, Connecticut, and since then there have been confirmed cases in most states each year. Some regions of the United States are at higher risk than others. Regions with higher tick populations have more reported cases of Lyme disease. Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic states have the highest prevalence. Western states have some of the lowest reported cases. Alaska, Oklahoma and Hawaii had the lowest number of cases in 2019. Click on this link to see the 2019 surveillance map of Lyme disease.

- Occupation: Individuals who work outdoors are more at risk for contracting Lyme disease. According to the CDC (2017), these occupations include but are not limited to construction, forestry, landscaping, farming, utility line work, and park management.

Signs/symptoms – The erythema migrans (EM) rash is the the cardinal sign that appears in up to 80% of infected individuals on average 7 days after a tick bite. See photos of varying EM rashes here. In addition to the EM rash, some individuals experience flu-like symptoms. Untreated Lyme disease can cause more severe symptoms, including swollen lymph nodes, heart problems, facial paralysis, nerve pain, and arthritis.

Transmission – Lyme disease is transmitted through the bite of the blacklegged tick.

Treatment – Oral antibiotics are given in the early stages of Lyme disease to treat EM and other symptoms that may be present. More severe cases of Lyme disease that result in neurological, cardiac, or anthric complications are also treated with antibiotics, but the course of treatment tends to be longer and more aggressive.

Complications – Lyme disease is rarely life-threatening, but long-term symptoms that accompany neurologic, cardiac, or arthritic Lyme disease can endure for months or years.

Prevention – Primary prevention of Lyme disease includes measures to prevent a tick bite. Click on this link to read about how to prevent tick bites on you, your pet, and in your yard. Secondary prevention of Lyme disease includes proper removal of a tick from the body. Click on this link to read about how to properly remove a tick. Seeking prompt treatment is also secondary prevention. The sooner someone can begin antibiotic treatment after a tick bite the less likely they will be to suffer severe or long-term complications.

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF)

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF), now called Spotted Fever Rickettsiosis (SFR) is a bacterial zoonotic infection caused by the bite of the American or brown dog tick or the Rocky Mountain wood tick.

Individuals at risk – Similar to Lyme disease SFR is more prevalent in certain parts of the United States. Arkansas, Missouri, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia account for half of the annual cases of SFR, while states like Hawaii and Alaska have very low rates. Older adults (60 years of age and older), immuno-compromised individuals, and males are also at higher risk.

Signs/symptoms – Symptoms of SFR include flu-like symptoms that may not prompt someone to get tested for SFR. In some cases, a rash will appear a few days after transmission.

Transmission – SFR is caused by the bite of the American or brown dog tick or the Rocky Mountain wood tick.

Treatment – Antibiotic treatment in the form of Doxycycline is the recommended means to treat SFR.

Complications – Affected individuals can have long-term complications. According to the CDC (2019), “some patients who recover from severe RMSF may be left with permanent damage, including amputation of arms, legs, fingers, or toes (from damage to blood vessels in these areas); hearing loss; paralysis; or mental disability. Any permanent damage is caused by the acute illness and does not result from a chronic infection” (CDC, 2019 https://www.cdc.gov/rmsf/symptoms/index.html). SFR can be deadly if not treated properly with an antibiotic.

Prevention – Primary prevention of SFR includes measures to prevent a tick bite. Click on this link to read about how to prevent tick bites on you, your pet, and in your yard

Ehrlichiosis

Ehrlichiosis is another bacterial zoonotic infection caused from the bite of the blacklegged tick or the lone star tick.

Individuals at risk

- Location: As with Lyme disease and SFR, geography plays a big role in risk for Ehrlichiosis. According to the CDC (2021), Missouri, Arkansas, North Carolina, and New York have the highest rates.

- Season: Time of year is more is more influential in risk for Ehrlichiosis compared to Lyme disease and SFR. Whereas cases of the latter two infections are more spread out throughout the year, cases of Ehrlichiosis are highest in the summer months. This is due to the life span of the lone star tick which is only associated with Ehrlichiosis and not Lyme disease or SFR.

- Age: Older adults (60 years of age and older), immuno-compromised individuals, and males are also at higher risk.

Signs/symptoms – Symptoms of Ehrlichiosis include flu-like symptoms that may not prompt someone to seek medical attention right away. In some cases, especially in children, a rash will appear a few days after transmission.

Transmission – Ehrlichiosis is caused from the bite of the blacklegged tick or the lone star tick.

Treatment – Antibiotic treatment in the form of Doxycycline is the recommended means to treat Ehrlichiosis. More severe cases are also treated with antibiotics, but the course of treatment tends to be longer and more aggressive

Complications – According to Cedars Sinai, complications are more likely to occur in immuno-compromised individuals and may include neurological, cardiac, and renal problems.

Primary prevention of Ehrlichiosis includes measures to prevent a tick bite. Click on this link to read about how to prevent tick bites on you, your pet, and in your yard. Secondary prevention of SFR includes proper removal of a tick from the body. Click on this link to read about how to properly remove a tick. Seeking prompt treatment is also secondary prevention. The sooner someone can begin antibiotic treatment after a tick bite the less likely they will be to suffer complications or death.

Check for Understanding: Tick-borne infections

Other Bacterial Infections

Plague

Plague is a bacterial infection that affects mammals who have been bit by a flea infected with the bacterium Yersinia pestis. The name itself is notoriously linked to the “black death” in the middle ages when the infection spread from Asia to Europe by way of cargo ships. Between 1347-1352 the plague killed almost one-third of Europe’s population. Nowadays, cases of plague are typically well-controlled and treated with antibiotics in the United States and other westernized countries. The use of the plague bacterium in bioterrorism, however, is a current potential threat. Click here to learn more about plague.

Types of plague – There are three types of plague, categorized by how it affects the body. Bubonic plague is the most common type and attacks the lymph node (at one time referred to as buboes). Septicemic plague attacks the bloodstream. Pneumonic plague attacks the lungs.

Individuals at risk – Plague is transmitted through fleas, so anyone who is more likely to encounter fleas are more at risk. Veterinarians, people who camp and hike, people who live in more rural areas, and people who live in crowded conditions (e.g. apartment complexes, residence halls, correctional facilities). Globally, the countries with the highest plague cases are in Africa, Asia, and South America.

Signs/symptoms – Symptoms of plague depend on which type of plague is transmitted. All three types are likely to cause flu-like symptoms (chills, fever, nausea, fatigue). Bubonic plague will cause tenderness and pain in areas with lymph nodes (e.g. neck, armpits, groin). Septicemic plague can cause bleeding from the mouth, nose, rectum, or under the skin as well as gangrene. Pneumonic plague can cause cough, difficulty breathing, and chest pain. Symptoms can intensify quickly and can lead to shock or death if left untreated.

Transmission – All types of plague are transmitted through a bite from a flea infected with the Yersinia pestis bacterium. Fleas can jump from mammal to mammal (e.g. dog to cat, cat to human, rat to dog, etc.), infecting anyone in its path.

Treatment – Prompt antibiotic treatment is vital to prevent serious complications and death from plague. In some cases, antibiotics may be given as a preventative.

Complications – As mentioned above, untreated plague can lead to gangrene and even death.

Prevention – Flea prevention is the primary means to prevent plague. Rodent-proof the environments in which you live, work, and play. Avoid leaving brush piles which can serve as nesting areas for squirrels, chipmunks, rats, and mice. Treat your domestic pets with flea preventative each month, use gloves when handling non-domestic mammals.

Leptospirosis

Leptospirosis is caused by a bacterium under the genus, Leptospira. Humans and other animals are at risk for infection. The infection is passed through contact with infected urine.

Individuals at risk – Individuals who come into contact with contaminated water or soil are most at risk. Certain occupations, such as mine workers, farmers, veterinarians, sewer workers, and military personnel have an increased risk of exposure. Individuals who may swim in natural bodies of water are also at elevated risk of exposure. Pets who drink or swim in contaminated waters can also become infected with leptospirosis. The CDC notes that risk increases after a flood due to the volume of standing water. Click here to read the info-graph on preventing leptospirosis infection after a hurricane or flood.

Signs/symptoms – Symptoms of leptospirosis can be mild and can mimic other infections and include typical flu-like symptoms in its first phase. Without proper treatment, the infection can cause liver and kidney damage.

Transmission – As noted above, Leptospira is transmitted through contact with water or soil in which an infected animal has urinated.

Treatment – Antibiotics are used to treat leptospirosis.

Complications – If left untreated, leptospirosis can lead to kidney and liver damage.

Prevention – Primary prevention for leptospirosis includes avoidance of recreational drinking from and swimming in untreated natural waters – that goes for both humans and pets. For at-risk occupations, proper clothing and footwear to protect the skin from coming into direct contact with water and soil is necessary for primary prevention.

Brucellosis

Brucellosis is a bacterial infection caused by types of the genus Brucella. Brucellosis is a threat to cattle, sheep, elk, deer, bison, swine, goats, and camels. When humans come into contact with infected mammals or consume unpasteurized dairy products from infected mammals they can become infected with brucellosis.

Individuals at risk – Brucellosis is also called Mediterranean fever. Cases are more common in countries surrounding the Mediterranean Sea (e.g. Portugal, Spain, Greece). South and Central American, Asian, and African countries are also associated with high cases due to the lack of public health programs to enforce pasteurization of dairy products and maintain healthy domestic animals and livestock. Since the 1940’s cases of brucellosis in the US have decreased dramatically due to improvements in these public health interventions.

Signs/symptoms in humans – Humans infected with the brucellosis bacterium will experience flu-like symptoms, muscle aches, and headache. In some cases, individuals may experience long-term symptoms such as swelling of certain body parts (e.g. testes, liver, spleen, endocardium), neurological problems, and arthritis.

Transmission – Brucella can enter the body through three main routes: ingestion, inhalation, or through the skin or mucous membranes. The bacterium is ingested via consuming products from an infected farm animal that have not been properly pasteurized. For example, drinking raw milk from an infected cow. Transmission through inhalation, skin, and mucous membranes is more common in individuals who work directly with the livestock (farmers, slaughterhouse workers), veterinarians, and hunters.

Treatment – Antibiotic treatment of doxycycline and rifampin is the traditional treatment for brucellosis. Alternative antibiotic treatment is given for special populations who cannot take this combination.

Complications – The most serious complications from brucellosis is to livestock. Bovine brucellosis can impact beef and dairy production, not to mention farm animal health and well-being. Complications from brucellosis in humans are rare. Less than 2% of cases result in death.

Prevention – Primary prevention for humans is avoidance of consuming unpasteurized milk and other dairy products (e.g. cheese, ice cream). Individuals who handle livestock should always wear gloves aprons, goggles, and masks to prevent transmission through skin and air. Primary prevention of cattle is vaccination.

Tetanus

Tetanus is caused by the bacterium, Clostridium tetani. This bacterium is naturally-occurring in the environment and can enter the bloodstream through contact with contaminated objects. Tetanus is also referred to as Lockjaw.

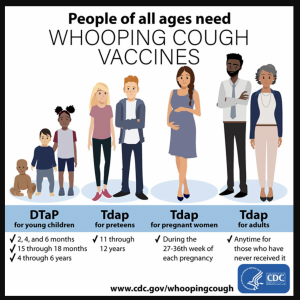

Individuals at risk – Because the bacterium naturally exists in the environment, anyone is potentially susceptible. According to the WHO, however, the majority of cases are among newborns and pregnant women who have not received the recommended Tdap vaccine. Other risk factors include being 60 years of age or older, having diabetes, being immuno-compromised and using IV drugs.

Signs/symptoms – As its synonym, Lockjaw, implies, one of the most common symptoms is “lockjaw” or the tightening of the jaw muscles. Muscle stiffness throughout the body is also a potential symptom. Other symptoms include fever, headache, trouble swallowing, and seizures.

Transmission – Tetanus is unique because it is not spread from person to person, rather the bacterium is spread to humans from inanimate objects. So it is not considered contagious. The classic example is stepping on a rusty nail, but spore of the bacterium can spread into one’s bloodstream via any wound on the body, via IV needles, insect bites, chronic sores, burns, and compound fractures.

Treatment – Tetanus requires immediate medical attention. A typical treatment regimen will include antibiotic therapy, tetanus immune globulin (TIG), and potentially wound care and administration of other drugs to control symptoms.

Complications – Tetanus can lead to severe complications due to how the paralytic effects of the bacterium. According to the Washington Health Department, “even with medical treatment, tetanus leads to death in about 1 to 2 in 10 cases, especially in those 60 years of age and older and in people who are unvaccinated. Other serious complications of tetanus include spasms of the vocal cords, broken bones, pneumonia (lung infection), and pulmonary embolism (blood clot in the lung)”. https://doh.wa.gov/you-and-your-family/immunization/diseases-and-vaccines/tetanus-lockjaw-disease#symptoms

Prevention – Primary prevention is proper vaccination with the Tdap vaccine, following the same schedule as was discussed in the bacterial infection chapter.

Anthrax

Anthrax is an uncommon but threatening bacterial infection caused by Bacillus anthracis. Like the tetanus bacterium the anthrax bacterium naturally exists in the environment, particularly in soil, and its spores can get into the bloodstream by inhalation, ingestion, injection, or through the skin (i.e. cutaneous ).

Individuals at risk – Occupations such as farmers, livestock workers, and veterinarians are at risk for contracting anthrax via contact with infected animals. Postal workers and first responders are at an elevated risk due to exposure during a potential bioterrorist attack.

Signs/symptoms – Symptoms will depend on how anthrax was transmitted. Click here to read the signs and symptoms of each type of anthrax (i.e. inhalation anthrax, gastrointestinal anthrax, injection anthrax, and Cutaneous anthrax)

Transmission – Just like tetanus, anthrax cannot be passed person-to-person and is therefore not considered contagious. Humans typically come into contact with anthrax via infected animals, especially farm animals. There has also been cases of the use of anthrax in bioterrorist attacks . According to the Texas Department of Health (2002), “Hoofed animals, such as deer, cattle, goats, and sheep, are the main animals affected by this disease. They usually get the disease by swallowing anthrax spores while grazing on pasture contaminated (made impure) with anthrax spores. Inhaling (breathing in) the spores, which are odorless, colorless, and tasteless, may also cause infection in animals and people. In the case of terrorism, large numbers of anthrax spores may be released into the air. Carnivores, including dogs and cats, are rarely infected. Amphibians, reptiles, fish, and most birds do not get anthrax” (para. 2).

Treatment – Antibiotics are the first line of treatment for all types of anthrax. Healthcare providers may also use antitoxins to treat some cases of anthrax. In severe cases, patients need to be hospitalized when more aggressive treatment is needed.

Complications – Anthrax can cause damage to multiple organs, sepsis, and even death if not treated properly.

Prevention – The primary form of prevention for anthrax, a vaccine, is not available to the general public. Instead, it is reserved to specific populations who are more at-risk due to possible exposure (e.g. laboratory workers, veterinarians). Secondary prevention in the form of antibiotic treatment after possible exposure is more common among the general public.

Watch this video to better understand how antibiotics work to combat anthrax. This is important in the event of a bioterrorist attack.

Check for Understanding: Bacterial zoonotic infections

Viral Infections

Rabies

Rabies is a life-threatening virus that is transmitted from a bite from an infected animal to humans and other animals. A bite from a rabid dog accounts for 99% of human rabies cases worldwide, whereas in Northern Central, and South America, a bite from a rabid bat accounts for most of rabies cases due to the successful vaccination program for dogs.

Individuals at risk – Individuals who may regularly be exposed to potentially rabid animals are most at risk for contracting the rabies virus. Bites from rabid dogs account for the majority of rabies cases worldwide, and bites from skunks, raccoons, foxes, and bats also responsible for rabies cases in the United States. Overall, based on rabies surveillance data from the CDC, cases of rabies in humans is very rare, with only 1-3 cases reported each year. In addition, individuals traveling to developing countries where there is a higher prevalence of rabid stray dogs are also at risk. According to the WHO, rabies is an example of a Neglected Tropical Disease (NTD) that disproportionately affects those living in poverty and often in rural locations. Eighty percent of rabies cases occur in rural locations, and most occurring in countries in Asia and Africa.

Signs/symptoms – The rabies virus attacks the central nervous system. There are two type of rabies based on presented symptoms. According to the WHO, 2021 (para. 9):

- Furious rabies results in signs of hyperactivity, excitable behaviour, hydrophobia (fear of water) and sometimes aerophobia (fear of drafts or of fresh air). Death occurs after a few days due to cardio-respiratory arrest.

- Paralytic rabies accounts for about 20% of the total number of human cases. This form of rabies runs a less dramatic and usually longer course than the furious form. Muscles gradually become paralysed, starting at the site of the bite or scratch. A coma slowly develops, and eventually death occurs. The paralytic form of rabies is often misdiagnosed, contributing to the under-reporting of the disease.

Transmission – Rabies is transmitted from a bite or scratch from a rabid domestic or wild animal. Transmission from rabid human to another human or from ingesting meat or raw milk from a rabid animal are possible but no cases have been confirmed in the world.

Treatment – Humans who may have been bitten or scratched by a potentially rabid animal should immediately flush the wound with soap and water for 15 minutes, then contact their healthcare provider to get a vaccination that same day.

Complications – Rabies can cause many severe complications in humans such as seizures, paralysis, hallucinations, and death.

Prevention – Vaccination is the primary prevention for rabies control. The vaccination program for domestic dogs in much of the world has almost eliminated the risk for getting rabies from a vaccinated domestic dog, causing public health officials to shift their focus to controlling rabies in wild life. The USDA has a national rabies management program wherein the Wildlife Services works with local, state, and federal government to distribute oral rabies vaccination (ORV) bait in affected wildlife areas throughout the United States. This ORV targets rabies variants in raccoons, coyotes, and foxes.

Education about rabies is also important. Humans should understand the signs of rabies in wild animals and contact their local animal control office to further diagnose and manage potential cases of rabies. Not all wild animals are at the same risk for rabies. For example, dogs, skunks, bats, raccoons, and foxes are more vulnerable, whereas squirrels, rabbits, and opossums are more resistant. Click here to learn more.

West Nile Virus

The West Nile Virus (WNV) is the most common mosquito-borne viral infection in the United States. It is often asymptomatic and there are currently no treatments or vaccines available.

Individuals at risk – Anyone living in an area with a mosquito population is at risk for contracting WNV. Older adults and individuals who are immunocompromised due to pre-existing conditions (e.g. diabetes, cancer) have a higher risk for more serious complications.

Signs/symptoms – about 80% of people infected with WNV are asymptomatic. About 1 in 5 people infected with WNV will present with flu-like symptoms (e.g. headache, vomiting, diarrhea) as well as have a fever and develop a rash. More rarely, in about 1 in every 150 people infected with WNV will develop more serious neurological symptoms. These are discussed under complications. It’s important for anyone who thinks they may have been exposed to get tested right away.

Transmission – The transmission cycle starts when mosquitos feed off of infected birds, then becoming infected themselves. Then, an infected mosquito bites a human or other mammal, thereby transmitting the virus to them . There have been a few rare cases of humans contracting WNV from exposure in a laboratory; blood transfusion or organ transplant; or a mother passing WNV to her newborn baby during pregnancy, childbirth, or breastfeeding. WNV is not transmitted from handling animals or dead birds or from ingesting meat or other animal by-products. Click here to see an illustration of the transmission cycle of WNV.

Treatment – There is no medical treatment or vaccination to prevent the transmission of WNV. OTC remedies can be used to ease flu-like symptoms. In more severe cases, the infected person may need to be hospitalized to receive additional treatment and monitoring.

Complications – The majority of people infected with WNV will fully recover in a few weeks with no serious complications. About 1 in 150 people infected with WN, however, will develop serious illness that may occur due to the central nervous symptom being attacked. According to the CDC, 2021 (paras. 5-7):

- Symptoms of severe illness include high fever, headache, neck stiffness, stupor, disorientation, coma, tremors, convulsions, muscle weakness, vision loss, numbness and paralysis.

- Severe illness can occur in people of any age; however, people over 60 years of age are at greater risk for severe illness if they are infected (1 in 50 people). People with certain medical conditions, such as cancer, diabetes, hypertension, kidney disease, and people who have received organ transplants, are also at greater risk.

- Recovery from severe illness might take several weeks or months. Some effects to the central nervous system might be permanent.

- About 1 out of 10 people who develop severe illness affecting the central nervous system die.

Prevention – Because there are no vaccines to prevent WNV, the best way to practice primary prevention is through mosquito control. At the individual level, people should wear protective clothing (e.g. long sleeves and pants) and wear mosquito repellant to avoid mosquito bites during peak months (late spring through early fall). Individuals should also prevent standing water around their homes as standing water attracts mosquitoes. Public health efforts are also in place to prevent standing water in public places, such as parks and other recreational sites.

Zika

Zika is a virus that is most commonly spread through a bite from an infected mosquito. Zika caught peoples’ attention in 2016 when there were outbreaks across the world. According to the CDC, however, there have been no locally-transmitted cases of Zika in the United States since 2018.

Individuals at risk – People living or visiting places during a Zika outbreak are at highest risk for Zika. Pregnant women are of particular focus due to the likelihood of Zika causing birth defects in newborns who contracted Zika in utero.

Signs/symptoms – Many people infected with Zika are asymptomatic. Some people may experience flu-like symptoms, have a fever, and develop a rash. The virus typically stays in the body for about a week. It’s important for anyone who thinks they may have been exposed to get tested right away.

Transmission – Zika can also be transmitted from person-to-person during unprotected sexual contact and from an infected pregnant woman to her baby.

Treatment – There is no medical treatment or vaccination to prevent the transmission of Zika. OTC remedies can be used to ease flu-like symptoms. In more severe cases, the infected person may need to be hospitalized to receive additional treatment and monitoring.

Complications – Most cases of Zika are mild and goes away without major health effects. In more serious cases where an infected woman passes the virus to her newborn, neurological birth defects, such as microcephaly, are possible. Click here to read more about birth defects caused by Zika.

Prevention – There is no vaccine for Zika. Therefore, individuals should prevent Zika transmission through the known routes. Individuals should take the same precautions to prevent mosquito bites as were mentioned for WNV. Condoms should be worn to prevent transmission through sexual contact. Women who are pregnant or could become pregnant should take the recommended precautions when traveling, and should not travel to anywhere there is a current Zika outbreak by using this interactive map.

Parasitic Infections

Malaria

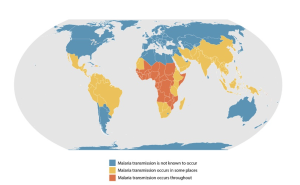

Malaria is a parasite that often infects the female Anopheles mosquito. Malaria transmission is frequent in tropical countries close to the equator, such as those in some parts of Central and South America and Sub-Saharan Africa. Worldwide, malaria is considered a major international public health problem. According to WHO’s latest World Malaria Report, there were an estimated 241 million malaria cases and 627,000 malaria deaths worldwide in 2020.

Individuals at risk – Figure 7.3 shows the prevalence of malaria transmission worldwide. Children and pregnant women are more vulnerable due to developing or weakened immunity, respectively. Individuals living in poor tropical areas in Sub-Saharan Africa are more at risk due to the weather conditions that promote a high mosquito population. Travelers to regions with high malaria transmission are also at risk and should discuss proper prevention with their healthcare provider before and after traveling to these areas.

Signs/symptoms – Malaria can present with a range of symptoms, from asymptomatic to severe illness. Click on here to read about the signs and symptoms at these stages.

Transmission – The most common route of transmission is from the bite of an infected female Anopheles mosquito. Malaria can also be transmitted from mother to newborn, from organ transplants, and from blood transfusions.

Treatment – Malaria is treated with anti-parasitic medication. The exact route of treatment will depend on several factors including severity of symptoms, age of patient and whether or not the patient is pregnant.

Complications – Complications are most often associated with severe malaria. Severe malaria can cause seizures; respiratory and kidney problems; anemia; hypoglycemia; metabolic acidosis ; and liver failure. “Any of these complications can develop rapidly and progress to death within hours or days”, (Trampuz, et al., 2003, p. 315).

Prevention – Primary prevention for malaria includes preventing mosquito bites by wearing protective clothing, using legitimate repellant, using netting, and eliminating standing water. In areas where malaria is prevalent a vaccine is available. Over the past couple of decades, international and national programs have made considerable progress in reducing malaria morbidity and mortality. These programs include interventions at various levels to control and eliminate the Anopheles mosquito population, vaccinate at-risk individuals, promptly diagnosing cases, and properly managing positive malaria cases. People living in areas where malaria transmission does not occur but who are traveling to places with malaria transmission should take the recommended preventative measures before and after traveling. Click here to learn more about worldwide prevention measures: Click here to learn about the CDC’s travel protocol for people living in the United States.

Tapeworm

Tapeworm is a parasitic infection caused by ingesting food or water contaminated with tapeworms or their eggs. Tapeworm can live in water, soil, and a living host. Tapeworms are visible to the naked eye, and can affect humans and other animals.

Individuals at risk – Certain conditions put individuals at a higher risk for tapeworm. Mayo Clinic (2022) summarizes these factors as the following (para. 13):

- Poor hygiene.Infrequent washing and bathing increases the risk of accidental transfer of contaminated matter to your mouth.

- Exposure to livestock.This is especially problematic in areas where human and animal feces are not disposed of properly.

- Traveling to developing countries.Infection occurs more frequently in areas with poor sanitation practices.

- Eating raw or undercooked meats.Improper cooking may fail to kill tapeworm eggs and larvae contained in contaminated pork or beef.

- Living in endemic areas.In certain parts of the world, exposure to tapeworm eggs is more likely. For instance, your risk of coming into contact with eggs of the pork tapeworm (Taenia solium) is greater in areas of Latin America, China, sub-Saharan Africa or Southeast Asia where free-range pigs may be more common.

Signs/symptoms – People infected with tapeworm may be asymptomatic. If symptoms do present, they will vary based on whether the larvae have remained in the intestines or moved outside of the intestines. Intestinal infection may cause nausea, diarrhea, loss of appetite, abdominal pain dizziness, weakness, and possibly weight loss. If the larvae have moved out of the intestines, symptoms may include headaches and neurological problems including seizures. The larvae can also form cysts that may be present.

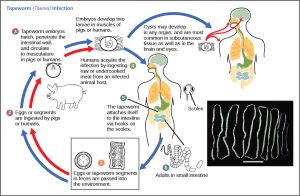

Transmission – As seen in Figure 7.4 the tapeworm is segmented. Once ingested, the tapeworm head attaches its head onto the wall of the small intestine of its host. Then, it begins to feed off of the food being digested by the host. The other segments detach from the head and can migrate outside the intestine and produce eggs. If the eggs produce larvae, the larvae also can move outside the intestines to other parts of the body.

Tapeworm can enter the body by:

- Eating undercooked, contaminated beef, pork, fish, or grains

- Coming into contact with contaminated feces, including direct contact with someone who may have tapeworm and didn’t wash their hands after using the bathroom

- Coming into contact with contact with contaminated surfaces that may have been touched by contaminated hands

Treatment – After testing for the tapeworms in a stool sample and getting a positive result, the infection is treated with anti-parasitic drugs, such as praziquantel or niclosamide.

Complications – Complications from tapeworm are rare. But if they do occur, they may include the following according to the Mayo Clinic (2022):

- Digestive blockage.If tapeworms grow large enough, they can block your appendix, leading to infection (appendicitis); your bile ducts, which carry bile from your liver and gallbladder to your intestine; or your pancreatic duct, which carries digestive fluids from your pancreas to your intestine.

- Brain and central nervous system impairment.Called neurocysticercosis (noor-o-sis-tih-sur-KOE-sis), this especially dangerous complication of invasive pork tapeworm infection can result in headaches and visual impairment, as well as seizures, meningitis, hydrocephalus or dementia. Death can occur in severe cases of infection.

- Organ function disruption.When larvae migrate to the liver, lungs or other organs, they become cysts. Over time, these cysts grow, sometimes large enough to crowd the functioning parts of the organ or reduce its blood supply. Tapeworm cysts sometimes rupture, releasing more larvae, which can move to other organs and form additional cysts.

- A ruptured or leaking cyst can cause an allergy-like reaction, with itching, hives, swelling and difficulty breathing. Surgery or organ transplantation may be needed in severe cases.

Prevention – Individual and public health measures can be taken to prevent tapeworm at primary and secondary levels. According to Mayo Clinic (2022) they include:

- Washing your hands with soap and water before eating or handling food and after using the toilet.

- When traveling in areas where tapeworm is more common, washing and cooking all fruits and vegetables with safe water before eating. If water might not be safe, be sure to boil it for at least a minute and then let it cool off before using it.

- Eliminating livestock exposure to tapeworm eggs by properly disposing of animal and human feces.

- Thoroughly cooking meat at temperatures of at least 145 F (63 C) to kill tapeworm eggs or larvae.

- Freezing meat for as long as seven to 10 days and fish for at least 24 hours in a freezer with a temperature of -31 F (-35 C) to kill tapeworm eggs and larvae.

- Avoiding eating raw or undercooked pork, beef, fish, and grains.

- Promptly treating dogs infected with tapeworm.

Cryptosporidium

Cryptosporidium is a parasitic infection also referred to as “crypto”. Infection by this microscopic parasite can affect the respiratory and gastrointestinal system of humans and other animals.

Individuals at risk – Individuals at a higher risk of getting crypto include children or anyone frequently around children (e.g. childcare workers, parents of young children, teachers), immuno-compromised individuals, individuals who handle livestock, people who drink from or swim in untreated water, and individuals who engage in anal sex.

Signs/symptoms – It’s common for crypto to cause no signs or symptoms. The most common symptom is watery diarrhea that can last up to two weeks. In addition, those infected may experience abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and potential weight loss. Immuno-compromised individuals may experience additional signs and symptoms that affect the respiratory system.

Transmission – Like tapeworm, the cryptosporidium parasite lives in the small intestine of an infected human or other animal host. The parasite is passed through feces, and can be found in water, soil, or food contaminated by infected fecal matter. A common way this parasite is transmitted is through drinking or swimming in contaminated water. Cryptosporidium is tricky because it’s tolerant to chlorine disinfection and alcohol-based hand sanitizers. Here is the complete list of how crypto can be transmitted.

Treatment – Most healthy individuals who have crypto recover without needing any treatment. Diarrhea can be eased with OTC anti-diarrheal medication, and dehydration can be prevented by drinking plenty of hydrating fluids. Immuno-compromised individuals may need to contact their healthcare provider for more guidance on how to treat the infection. If necessary, an anti-parasitic medication can be given.

Complications – The biggest concern is dehydration as a result of the diarrhea and vomiting, so proper hydration is important as was noted under “treatment”. The infection could more seriously affect the gastrointestinal system or the respiratory system in immuno-compromised individuals and may require more medical attention.

Prevention – Primary and secondary prevention of crypto include protecting yourself and other from transmission via water, food, soil and feces.

1). Preventing transmission from contaminated water:

- Although disinfecting water with chlorine and using hand sanitizer do not prevent the spread of cryptosporidium, washing hands with regular soap and water – especially before eating; before and after sexual contact; after being outdoors; after using the restroom; after sneezing, coughing, or blowing your nose; and handling certain animals – has shown to be effective at preventing the spread of the parasite.

- If you are unsure of the source of your drinking water you should do the following according to the CDC:

- Use commercially bottled water.

- Boil water for at least 1 minute and left to cool. At elevations above 6,500 feet (1,981 meters), boil for 3 minutes.

- Use a filter designed to remove Crypto.

- The label might read ‘NSF 53’ or ‘NSF 58.’

- Filter labels that read “absolute pore size of 1 micron or smaller” are also effective.

- If there has been a boil order in your community, you should comply with the instructions.

- Do no drink or swallow swimming water.

- Do not let anyone who has crypto swim in public or residential water or pools.

- When swimming with infants, toddlers, and children, be sure to take frequent restroom breaks and constantly check diapers.

2). Preventing transmission from exposure to contaminated feces:

- In places where individuals are in close proximity to each other (e.g. childcare facilities, camps, schools, correctional institutions), anyone who has crypto should be separated until they no longer have diarrhea (typically around 2 weeks).

- Abstain from sexual contact or use condoms when engaging in vaginal or anal sex and dental dams when engaging in oral sex until diarrhea as stopped.

Check for Understanding: Viral and parasitic zoonotic infections

Pets and Public Health

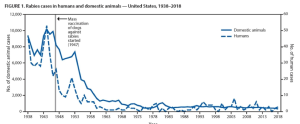

You might not think of it, but disease prevention can start right at home, and with your pets. Roughly 100 humans died a year in the early 1900s due to rabies in the U.S., though since 1960 only one or two people die from rabies each year. Thanks to public health professionals and policy makers several successful strategies have been employed which account for the decline in rabies transmission and death such as surveillance programs, animal import regulation, animal control programs, and availability of post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) for rabies (CDC and Atlas). Additionally, the mass vaccination of dogs against rabies started in the late 1940s. Today, 41 states and D.C. have pre-exposure rabies vaccination laws in place for domestic dogs, cats, or ferrets. Explore vaccination laws in the United States here.

In 2007, the CDC declared that the U.S. was canine (dog) rabies free. Now, 70% of all rabies infections are acquired from bats in the U.S.. Other countries though are still struggling to control rabies infections from dogs. “Dog rabies remains common in many countries and exposure to rabid dogs is still the cause of over 90% of human exposures to rabies and of 99% of human rabies deaths worldwide” (CDC, 2020). View rabies status by country here. Dog vaccination measures require constant effort and resources to maintain a stable decrease in infections which prohibits implementation in developing countries. The United States spends $245 to $510 million annually on rabies control which is considered as draining public health resources in other countries since rabies is viewed as a wild and domestic animal issue.

Vultures: Public Health Heroes

Don’t judge a bird by it’s cover: Vultures play key roles to conserve the health of our world. Vultures are birds of prey classified as scavengers. As opposed to predatory raptors such as eagles and hawks, vultures get most of their nourishment by feeding off already dead and decaying animals. There are 23 species of vultures around the world, and most of them are now endangered due to man-made causes, despite the large amount of research that shows the importance of vultures in maintaining a healthy ecosystem.

The anatomy of a vulture allows them to eat from the corpses of animals who may have died from an infectious disease. Their heads are bald to prevent the harboring of infectious agents in feathers. Their urine and feces are disinfectants to their feet after standing on a corpse. Even their vomit is their defense mechanism (again, vultures are not predatory birds). If an animal dies of an infectious disease and a vulture eats the corpse of this animal, they stop the spread of infection. Otherwise, the infectious agent that killed that animal can spread into soil, water, or can become airborne. In short, vultures stop the means of transmission of infectious disease, such as tuberculosis, anthrax, and rabies.

Watch video one and video two to learn more about these amazing creatures.

Discussion questions

- Describe how to properly remove a tick from yourself or your pet.

- Discuss the current global and national state regarding rabies cases. How has mandated vaccination impacted rabies cases in the US? Most rabies cases come from where?

- Vultures are endangered in many parts of the world. Discuss how risk for infectious disease would increase without the existence of vultures.

Chapter activities

- Contact your local mosquito control office, and ask them how they tackle mosquito control in their community. Record their responses.

- Black and turkey vultures are fairly populous in Maryland and surrounding states. Plan a field trip to somewhere in town or in a more rural location to observe their behavior: How they perch, how they circle in the air as a group, how they collectively work on carcasses, etc. Record your field notes.

references

Black Death. (2020, July 6). History; A&E Television Networks. https://www.history.com/topics/middle-ages/black-death

Britannica. (n.d.). Mammal. Britannica Kids. https://kids.britannica.com/kids/article/mammal/353414#:~:text=A%20mammal%20is%20an%20animal

Cedars Sinia. (n.d.). Ehrlichiosis. Cedars-Sinai. https://www.cedars-sinai.org/health-library/diseases-and-conditions/e/ehrlichiosis.html#:~:text=Ehrlichiosis%20is%20an%20illness%20caused

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). West Nile virus. https://www.cdc.gov/westnile/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.-a). Press Release: US declared canine-rabies free. https://www.cdc.gov/media/pressrel/2007/r070907.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.-b). Protect yourself from Leptospirosis. https://www.cdc.gov/leptospirosis/pdf/protect-yourself-leptospirosis-P.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Malaria: Disease directory. CDC.gov. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/diseases/malaria

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014, November 5). Birth defects. https://www.cdc.gov/zika/healtheffects/birth_defects.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018a). Zika travel information. CDC.gov. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/page/zika-information

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018b, October 11). Vaccination of cattle. https://www.cdc.gov/brucellosis/veterinarians/cattle.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018c, October 17). Risk of exposure: Brucellosis. https://www.cdc.gov/brucellosis/exposure/areas.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018d, October 26). Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever. https://www.cdc.gov/rmsf/communication/rmsf-can-be-deadly.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018e, December 21). Lyme disease rashes and look-alikes | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/signs_symptoms/rashes.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019a). Lyme Disease maps: Most recent year. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/datasurveillance/maps-recent.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019b). Parasites: Malaria. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/malaria/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019c). Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/plague/prevention/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019d). Rabies surveillance data in the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/rabies/location/usa/surveillance/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019e). Risk of exposure. https://www.cdc.gov/leptospirosis/exposure/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019f). Sources of infection & risk factors. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/crypto/infection-sources.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019g). Tetanus. https://www.cdc.gov/Tetanus/about/causes-transmission.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019h). Tetanus. https://www.cdc.gov/tetanus/about/diagnosis-treatment.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019i). Transmission. https://www.cdc.gov/brucellosis/transmission/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019j). Treatment. https://www.cdc.gov/brucellosis/treatment/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019k). Who is at risk. https://www.cdc.gov/anthrax/risk/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019l, March 18). What we know about Zika and pregnancy. https://www.cdc.gov/pregnancy/zika/pregnancy.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019m, April 22). Tick removal. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/removal/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019n, July 9). Emerging and zoonotic infectious disease laws. https://www.cdc.gov/phlp/publications/topic/zoonotic.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019o, October 7). Cryptosporidiosis: Fact sheets. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/crypto/gen_info/prevention-general-public.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019p, November 7). Recent Lyme disease surveillance data | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/datasurveillance/recent-surveillance-data.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020a). Epidemiology and statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/rmsf/stats/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020b). Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/brucellosis/prevention/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020c). Transmission. https://www.cdc.gov/rmsf/transmission/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020d, February 24). Lyme Disease Risks | NIOSH | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/lyme/risks.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020e, March 26). Statistics: Ehrlichiosis. https://www.cdc.gov/ehrlichiosis/stats/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020f, April 6). Wild animals: Rabies in the US. https://www.cdc.gov/rabies/location/usa/surveillance/wild_animals.html#:~:text=Wild%20animals%20accounted%20for%2092.7

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020g, August 27). Preventing tick bites. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/prev/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020h, October 27). Lyme arthritis. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/treatment/LymeArthritis.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020i, November 19). Antibiotics to prevent anthrax. https://www.cdc.gov/anthrax/prevention/antibiotics/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020j, November 19). How people get anthrax. https://www.cdc.gov/anthrax/transmission/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021a). One Health Zoonotic Disease Prioritization (OHZDP). https://www.cdc.gov/onehealth/what-we-do/zoonotic-disease-prioritization/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021b). Treatment of anthrax infection. https://www.cdc.gov/anthrax/treatment/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, May 9). Ehrlichiosis. https://www.cdc.gov/ehrlichiosis/index.html#:~:text=These%20bacteria%20are%20spread%20to

Collins, S., White, J., Ramsay, M., & Amirthalingam, G. (2014). The importance of tetanus risk assessment during wound management. IDCases, 2(1), 3–5.

Hamann, B. (2007). Disease: Identification, Prevention, and Control (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

Heyneman, D. (1996). Cestodes (S. Baron, Ed.). PubMed; University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK8399/

Ingeno, L. (2021, March 30). In Peru, Penn researchers race to vaccinate dogs as two epidemics collide. https://www.pennmedicine.org/news/news-blog/2021/march/in-peru-penn-researchers-race-to-vaccinate-dogs-as-two-epidemics-collide

Koury, R., & Warrington, S. J. (2020). Rabies. PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448076/

Liu, Q., Wang, X., Liu, B., & et al. (2017). Improper wound treatment and delay of rabies post-exposure prophylaxis of animal bite victims in China: Prevalence and determinants. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 11(7). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0005663

Mayo Clinic. (n.d.). Anthrax: Symptoms and causes. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/anthrax/symptoms-causes/syc-20356203#:~:text=The%20most%20serious%20complications%20of

Mayo Clinic. (2017). Tapeworm infection: Symptoms and causes. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/tapeworm/symptoms-causes/syc-20378174

Mayo Clinic. (2021, May 5). Plague: Symptoms and causes. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/plague/symptoms-causes/syc-20351291

Mayo clinic. (2018). Malaria: Diagnosis and treatment. MAYO CLINIC. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/malaria/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20351190

Nemours KidsHealth. (n.d.). Tapeworm (for parents). https://kidshealth.org/en/parents/tapeworm.html#:~:text=If%20this%20infected%20poop%20gets

Plaza, P.I., Blanco, G. and Lambertucci, S.A. (2020), Implications of bacterial, viral and mycotic microorganisms in vultures for wildlife conservation, ecosystem services and public health. Ibis, 162: 1109-1124. https://doi.org/10.1111/ibi.12865

Quinzio, M. D., & McCarthy, A. (2008). Rabies risk among travellers. CMAJ, 178(5), 567–567. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.071443

Roome, A., Spathis, R., Hill, L., & et al. (2018). Lyme disease transmission risk: Seasonal variation in the built environment. Healthcare, 6(3), 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare6030084

Salyer, S. J., Silver, R., Simone, K., & et al. (2017). Prioritizing zoonoses for global health capacity building. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 23(13). https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2313.170418

Smithsonian’s National Zoo. (2019, February 15). Anthrax epidemiology and vultures. https://nationalzoo.si.edu/global-health-program/anthrax-epidemiology-and-vultures

Society, N. G. (2020, January 27). The role of scavengers: Carcass cunching. https://www.nationalgeographic.org/article/role-scavengers-carcass-crunching/7th-grade/

Tan, K. R., & Arguin, P. M. (n.d.). Malaria: Chapter 4. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2020/travel-related-infectious-diseases/malaria#1939

Texas Department of Health. (n.d.). Basic fact sheet: Anthrax in animals. https://www.dshs.state.tx.us/idcu/disease/anthrax/information/anthpub.pdf

Trampuz, A., Jereb, M., Muzlovic, I., & et al. (2003). Clinical review: Severe Malaria. Critical Care, 7(4), 315. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc2183

United States Department of Agriculture. (n.d.-a). Facts about brucellosis. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/animal_diseases/brucellosis/downloads/bruc-facts.pdf

United States Department of Agriculture. (n.d.-b). National rabies management program. Https://Www.aphis.usda.gov/Aphis/Ourfocus/Wildlifedamage/Programs/Nrmp/CT_Rabies#:~:Text=The%20goal%20of%20the%20program,Rabies%20vaccination%20targeting%20wild%20animals.

Washington State Department of Health. (n.d.-a). Tetanus Disease. Retrieved October 25, 2022, from https://doh.wa.gov/you-and-your-family/immunization/diseases-and-vaccines/tetanus-lockjaw-disease#risk

Washington State Department of Health. (n.d.-b). Tetanus disease. Retrieved October 25, 2022, from https://doh.wa.gov/you-and-your-family/immunization/diseases-and-vaccines/tetanus-lockjaw-disease#symptoms

World Health Organization. (2018a, May 9). Tetanus. World Health Organization: WHO. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tetanus

World Health Organization. (2018b, August 28). New global strategic plan to eliminate dog-mediated rabies by 2030. World Health Organization: WHO. https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/new-global-strategic-plan-to-eliminate-dog-mediated-rabies-by-2030

World Health Organization. (2020a, April 21). Rabies. World Health Organization: WHO. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/rabies

World Health Organization. (2020b, July 29). Zoonoses. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/zoonoses

World Health Organization. (2021). World malaria report 2021. https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2021

World Health Organization. (2022, July 26). Malaria. World Health Organization: WHO. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malaria

Remember, humans are animals!

Tissue death that will result in skin looking black.

Remember that a mammal is an animal that breathes air, has a spine, and whose females have mammary glands. There are more than 5,000 species of mammals. So, humans are just 1/5,000th of all mammalian species!

In 2001, shortly after the 9/11 terrorist attack, “letters laced anthrax began appearing in the U.S. mail. Five Americans were killed and 17 were sickened in what became the worst biological attacks in U.S. history” (Federal Bureau of Investigation, n.d., https://www.fbi.gov/history/famous-cases/amerithrax-or-anthrax-investigation)