4 Chapter 4: Viral Infections

Brandye Nobiling

Chapter Objectives:

- Identify viral infections by the route of transmission.

- Identify individuals most at risk for selected viral infections.

- Differentiate among types of hepatitis.

- Differentiate between chicken pox and shingles.

- Describe primary and secondary means of prevention for selected viral infections.

- Explain recommended vaccination schedules for selected viral infections.

- Explain the now revoked scientific study that helped spark the current anti-vaccination movement.

introduction

Viruses are very tiny microscopic infectious agents that, unlike bacteria, need a host to survive. When a virus enters the body, it attaches to a host cell and multiplies. This chapter covers viral infections of the respiratory and gastrointestinal systems that are of public health concern. A discussion on vaccination policy as well as the controversial fraudulent article that sparked the anti-vaccination movement.

Respiratory viral infections

Influenza

Influenza, also referred to as “the flu”, is the broad term referring to various types of a respiratory virus. Three types infect humans and are categorized as influenza virus Type A, Type B, and Type C. Influenza Types A and B are the most prevalent and are responsible for causing epidemics and pandemics. For example, the H1N1 pandemic of 2009 was a Type A influenza strain. Type C is considered endemic and does not cause severe respiratory illness; Types A and B, however, are associated with causing serious respiratory signs and symptoms.

Individuals at risk – Influenza Types A and B are very contagious, so anyone can get the flu. Individuals most at risk for complications from the flu are those age 65 and older, those with compromised immunity due to having chronic conditions such as heart disease or diabetes, and those who are not vaccinated. Click here for a comprehensive list of individuals at risk for flu complications

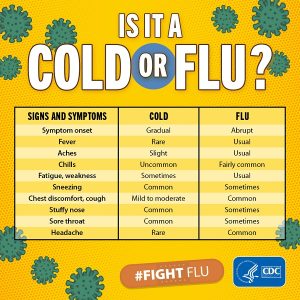

Signs/Symptoms – Symptoms of influenza usually develop suddenly and can include chills, fever, headache, fatigue, muscle aches, and cough. It is common to mistake cold symptoms for the flu and vice versa. Figure xx delineates common symptoms of the flu and the common cold.

Transmission – Influenza is very contagious and can spread via direct contact with an infected person’s respiratory droplets (e.g. when they cough, sneeze, or even talk) or via indirect contact with a contaminated inanimate object (e.g. a computer keyboard contaminated with the influenza virus after being touched by an infected person). People with the flu are contagious first the first few days after exposure. According to the CDC, it is possible for otherwise healthy adults who have the flu to pass the virus onto others a day or so before their symptoms appear. Transmission is more likely in winter months (i.e. “flu season), because cold weather brings people inside. Being in close proximity (i.e. within six feet) to others can increase the chance of transmitting the virus.

Treatment – For otherwise healthy adults, symptoms are often managed with rest and OTC medication to alleviate symptoms. Antiviral medications are available, however, and can be prescribed for individuals at-risk for serious complications from the flu.

Complications – Influenza is not the leading cause of death in the US like it was in 1900, but it is still in the top ten list of leading causes of death (currently the ninth cause of death in the US). Therefore, complications of the flu can be serious and even deadly. Pneumonia is the most common serious complication from the flu, as well as other infections and heart problems. The best way to prevent complications from the flu is to get the seasonal flu vaccine. Prompt antiviral treatment for at-risk people diagnosed with the flu is also important to prevent symptoms from worsening.

Prevention – Primary prevention of the flu is getting the vaccine every year and practicing sanitary behaviors. Due to its ability to mutate, a new vaccine must be made each year. The CDC recommends everyone six months old and older get the season flu vaccine each year. In addition to getting vaccinated, practicing sanitary and hygienic behaviors, such as sneezing and coughing in the fold of the arm as opposed to in the hand, washing your hands properly, disinfecting surfaces, and avoiding work and crowds if you feel sick, can also prevent getting the flu as well as spreading it to others.

COVID-19 and Public Health

In early 2020 a new coronavirus, caused by a SARS-Co-V-2 reached pandemic levels. COVID-19 (named for the virus type and the year it was first discovered) is a respiratory viral infection transmitted via respiratory droplets. COVID-19 introduced the public to many facets of infectious disease, especially emergency response to a worldwide outbreak.

The scientific community learned early-on in the pandemic how the virus was transmitted, and public health agencies began to enforce emergency management protocol like quarantine and mask wearing. Although not new protocol in the history of public health, these mandates impacted the world on emotional and societal levels.

The current stage in the pandemic includes vaccine recommendations (and in some settings, mandates) and the fact that COVID-19 will continue to exist as an endemic infectious disease as we are faced with evolving variants. The public health response has since shifted to focusing more on mental and emotional impact of this virus, while monitoring the biological impact.

COVID-19 and Health Educators: Impact on Professional Practice

The mental, emotional, and societal effects of COVID-19 have been heavily researched since the beginning of the pandemic. But how has the pandemic affected public health professionals? One study examined health educator’s reported self-efficacy in professional practice, competencies as defined by the National Commission for Health Education Credentialing (NCHEC), and changes in the use of technology during the COVID-19 pandemic. Researchers found health educators had highest levels of reported self-efficacy in maintaining regular communication with colleagues and supervisors and, for those in a teaching role, communicating with students since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, reported self-efficacy was much lower when communication was in the context of identifying media and strategies and modifying existing methods of communication to priority populations. These findings imply that health educators are more confident in communicating regularly with those whom they work the most closely, but feel less confident in determining the best practices to reach target audiences during an unprecedented time.

The most telling findings were the low levels of self-efficacy in maintaining a work-life balance and managing personal and professional stress since COVID-19. This could be due to the transition to telework and working from home amongst domestic distractions. These dual responsibilities could be the cause for this lack of self-efficacy in juggling a work-life balance, and making it difficult to manage pressures when working in an environment when professional and personal stress collide.

In terms of areas of responsibility, levels of self-efficacy were relatively low across the selected competencies included in the survey. The highest levels of self-efficacy were associated with Area 8: Ethics and Professionalism, and the lowest levels of self-efficacy associated with Area 1: Assessment of Needs and Capacity, particularly with their ability to recruit and engage community members in needs assessment since COVID-19.

Findings from this study imply a need for a better support structure and professional development opportunities for health educators, not just during a global pandemic, but during all eras of their professional career. Worksites who employ health educators should offer employment assistance programs (EAP) that provide specialized services for those who work to serve others. States can implement programs to enhance health educator’s self-care and help them find a better work-life balance. The Maryland Department of Health, for example, along with the Behavioral Health Administration (BHA) and MedChi, the Maryland State Medical Society, jointly sponsor a webinar series targeting behavioral health and medical care workers with the goal to improve resiliency and self-care and to help combat the various stressors these professionals face, (Maryland Department of Health, n.d.).

Public health professional associations should offer needs assessment, leadership and management, and advocacy training for at annual meetings or throughout the year as webinars. Findings from this study show the need for more professional development in these competencies, and this need is underscored with the revised competency framework in which leadership and advocacy are now standalone areas of responsibility and best methods for reaching priority populations during needs assessments may have changed.

The start of the COVID-19 pandemic demanded that quick decisions be made, even if these decisions were not based on adopting best practices or sound scientific methodology. The goal was to survive day-to-day. Coming into 2022, however, we are in a different place with vaccines, tests, and more knowledge available. There is opportunity for reflection. Now is the time to re-imagine things like educational formats, best uses of technology, and reaching priority populations, as well as the need for health educators to voice their needs as people who serve people. Health educators are innovators, and can spearhead transformations to professional practice, policy, and research based on lessons learned during such an unprecedented time in global history.

Measles

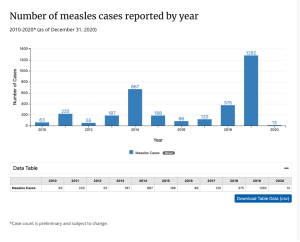

Measles is a viral infection that used to be very prevalent in the United States until the 1960’s when mandatory vaccination of children led to a drastic decline in cases. Due to the recent anti-vaccination trend, however, we are seeing an increase in measles cases. Figure xx illustrates the sharp increases of cases in 2014 and 2019.

Individuals at risk – Unvaccinated children are at the highest risk of contracting and dying from measles. Pregnant women are also at risk. Globally, measles remains a common cause of death, especially in developing countries in Africa and Asia.

Signs/Symptoms – Symptoms typically appear about 10 days after exposure to the virus. Koplik’s spots, white dots in the mouth and on the back of the throat that can be seen with the naked eye, can appear a couple of days after exposure. The cardinal sign is the development of a rash all over the body. The rash appears a few days (3-5 days) after exposure. In addition to the rash, measles causes a high fever, cough, and some cold-like symptoms.

Transmission – Measles is highly contagious. According to the CDC, “Measles is so contagious that if one person has it, up to 90% of the people close to that person who are not immune will also become infected,” (CDC, 2020, para. 3). The CDC recommends that you contact your health care provider immediately if you think you have been exposed. The measles virus is spread through direct contact with respiratory droplets (e.g., someone coughs or sneezes near you). The measles virus can survive and linger in the air for up to two hours after the infected person leaves a room.

Treatment – There is no antidote for measles. Unlike bacterial infections that are treated with antibiotics, viruses do not have targeted treatment. Some measures can be taken to reduce the risk, such as post-exposure measles vaccination, as well as medication to ease symptoms, such as fever reducing medication (e.g., Tylenol).

Complications – Complications from measles can be serious and those at risk for getting measles are the same as those most likely to suffer complications. Measles can cause subsequent infection, such as pneumonia and encephalitis , pregnancy complications, such as low birth weight, and even death.

Prevention – Vaccination is the primary means of prevention for measles. The vaccine that protects from measles is the MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) vaccine. It also protects against two other viral infections, mumps and rubella. “The CDC recommends all children get two doses of MMR (measles-mumps-rubella) vaccine, starting with the first dose at 12 through 15 months of age, and the second dose at 4 through 6 years of age. Children can receive the second dose earlier as long as it is at least 28 days after the first dose,” (CDC, 2021, para. 2). Adults who are not presumed to be immune as well as anyone planning to travel should also get vaccinated as needed.

In addition, oral health care providers should be on the lookout for Koplik’s spots in their patients. Because these are often the first sign of measles, oral health care providers are in a unique position in early detection of the virus.

Varicella (Chicken Pox and Shingles)

Chicken pox and shingles are both caused by the varicella-zoster virus (VZV), a type of herpes virus. VZV is highly contagious, and once a person is exposed, they develop chicken pox. After they recover from chicken pox, the virus stays dormant in the spinal cord. Many years later it can re-activate and cause shingles to develop. Everyone exposed to VZV will develop chicken pox first and shingles later in life.

Individuals at risk – Prior to the availability of the chicken pox vaccine, chicken pox would typically occur early in life during childhood. Some parents would actually expose their children who had not yet had chicken pox to other children who had chicken pox in order to allow their children to get chicken pox and develop acquired immunity early in life and “get it over with” so to speak. There are still reports of parents doing this as an alternative to vaccination. This is not recommended and can be dangerous. In fact, having these “pox parties”, as they are called, can increase risk for serious complications of chicken pox. Risk for shingles increases with age as immunity to VZV wears off over time.

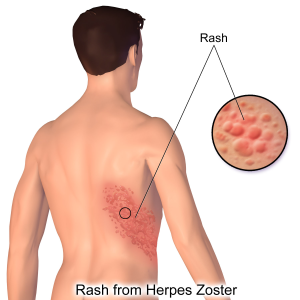

Signs/Symptoms – Initial symptoms of chicken pox include flu-like symptoms: cough, fever, loss of appetite, and headache. The cardinal rash of itchy, fluid-filled blisters follows and typically lasts about a week. Shingles develops as a painful rash on one side of the body. The distribution of the rash is compared to a tree branch, as the rash commonly follows nerve branches on the trunk of the body. The shingles rash can also appear anywhere else on the face or body. The symptoms that occur with chicken pox are also likely with shingles.

Transmission – Chicken pox is highly contagious and can be transmitted via direct contact with an infected person. Rarely, a person who has already has developed immunity to chicken pox will get it a second time. This is called breakthrough chicken pox, and typically is very mild. Shingles is not contagious and is not passed person-to-person. Rather, shingles is the result of the re-activation of the VZV virus many years – even decades – after having chicken pox.

Treatment – Because chicken pox and shingles are caused by a virus, there is no pharmaceutical treatment. At-home remedies for chicken pox such as application of calamine lotion on the rash and oatmeal baths can help alleviate itching. These same treatments are used to ease pain and itching of the shingles rash as well. Antiviral medications can be prescribed to treat shingles and are most effective if started as soon as symptoms appear.

Complications – Complications from chicken pox are rare, but if they do occur are most likely to occur in infants, adults, pregnant women, and individuals with a weakened immune system. Complications can include pneumonia or other subsequent infections, dehydration, and even death. The most common complication of shingles is long-term nerve damage, called postherpetic neuralgia (PHN). Other complications, such as subsequent infections, vision loss, and death can also occur from shingles. The best way to avoid these complications is to get vaccinated for chicken pox and shingles.

Prevention – Vaccination is the best way to prevent chicken pox and shingles. The CDC recommends the 2-dose vaccination for chicken pox, the first dose is given between 12-15 months of age and the second dose is given between 4-6 years of age. The shingles vaccination, Shingrix, is recommended for all adults 50 years of age and older. Shingrix is also a two-dose vaccination with the second dose given 2-6 months after the first dose. Acquired immunity from the vaccine lasts up to four years. Individuals should discuss subsequent vaccination with their health care provider. There is no maximum age for the shingles vaccine.

Infectious Mononucleosis

Infectious mononucleosis, aka “mono” is a highly contagious condition caused by the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), which is a type of herpes virus. The EBV is very contagious. It is estimated that 90% of individuals in the United States have been infected by the time they are 35 years of age. Like other types of herpes viruses, once a person is infected, the EBV stays in their body for the rest of their life, typically in a de-activated state. A person is not contagious in the de-activated state.

Individuals at risk – Teenagers and young adults are often the most susceptible to contracting the EBV.

Signs/Symptoms – Typically symptoms only appear upon initial infection of EBV and may take several weeks to appear after exposure. One of the most common symptoms of mono is extreme fatigue. Other symptoms include fever, chills, headaches, sore throat, enlarged spleen, and swollen lymph nodes.

Transmission – Mono often referred to as the “kissing disease” because it is spread through saliva. EBV can also be spread by sharing drinks or utensils.

Treatment – No specific treatment for mono exists because it is a viral infection. Treatment options include OTC medication to reduce symptoms and prescription corticosteroids to reduce inflammation.

Complications – Mono typically is not a serious disease, but sometimes complications can arise. Possible complications include a ruptured spleen, kidney problems, heart problems, and neurological problems.

Prevention – Due to the highly contagious nature of EBV, mono is difficult to prevent at the primary level. Secondary prevention includes isolation of individuals who have active symptoms and avoidance of sharing drinks, utensils, etc. with others as well as not kissing others.

Gastrointestinal (gi) and other viral infections

Hepatitis

Hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver caused by the hepatitis virus. Hepatitis can be acute or chronic if not infection endures. Currently, there are several strains of Hepatitis, but hepatitis virus A (HAV), hepatitis virus B (HBV), and hepatitis virus C (HCV) are of particular concern in the US and many other countries worldwide.

Individuals at risk – Besides individuals having unprotected sexual intercourse, living/being born outside of the US, and sharing IV needles are risk factors for acquiring HBV and HCV. “Non-US-born people account for 70% of all chronic hepatitis B infections in the United States,” (CDC, 2020, para. 2). HBV is prevalent in many countries in Asia, the Pacific Islands, and Africa. HBV is more prevalent worldwide vs. the US. In the United States, current statistics show HAV and HCV to be more prevalent. And recent trends are showing IVD use the leading risk factor for HAV and HCV cases in the US, likely connected to the opioid epidemic and people injecting heroin and fentanyl after purchasing them “on the street”. According to the CDC’s 2019 data on HCV the leading risk factor was IVD use with 67% of people infected with acute HCV reporting IVD use. The US has been seeing an increase in HVA rates over the past seven years. According to the CDC, this is due to “unprecedented person-to-person outbreaks reported in 31 states primarily among people who use drugs and people experiencing homelessness,” (CDC, 2021, para. 1).

Risk for developing chronic HVB increases the younger the age one contracts the virus. According to the Hepatitis B Foundation:

- More than 90% of infants that are infected will develop a chronic hepatitis B infection.

- Up to 50% of young children between 1 and 5 years who are infected will develop a chronic hepatitis B infection.

- 5-10% of healthy adults 19 years and older who are infected will develop a chronic hepatitis B infection (that is, 90% will recover from an exposure), (Hepatitis B Foundation, n.d. para. 3).

Therefore, proper screening of pregnant women is vital to prevent transmission of HBV to newborns. As for HCV cases, about half of acute HVC cases will progress to chronic HCV. The asymptomatic nature of hepatitis complicates matters, because a person may not know they are infected and therefore will not go seek medical intervention (e.g., testing, treatment). Having recommendations in place to test everyone regardless of symptoms will help catch those asymptomatic cases and prevent further transmission.

Signs/Symptoms – Hepatitis is often a silent disease, meaning it is common for no signs or symptoms to be present even though a person has been infected with the virus. According to the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), “More than half of persons living with hepatitis do not know that they have the virus. Thus, they are at risk for life threatening liver disease and cancer and unknowingly transmitting the virus to others,” (HSS, 2016, para. 4).

If symptoms do occur, they will become present anywhere from 2 weeks to three months after exposure and include flu-like symptoms of fever, fatigue, nausea, abdominal pain, and lack of appetite. Because hepatitis affects the liver, tell-tell signs of liver damage such as gray-colored stools, dark urine, and jaundice (i.e., yellowing of the skin or whites of the eyes) may occur.

Transmission – Hepatitis A, B, and C can all be passed person-to-person via direct contact with contaminated blood, saliva, semen, or vaginal fluid. HAV is also passed via infected fecal matter that can be spread to food or water as a result of improper hand washing followed by food handling. Hepatitis can spread through blood and other body fluids via sharing contaminated needles, unprotected sexual intercourse, and from mother-to-baby. Hepatitis is unique in that it can survive for days outside of a host and remain contagious.

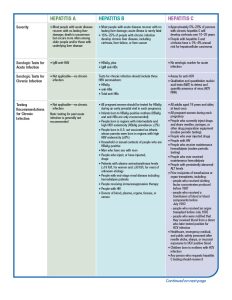

Treatment – Treatment depends on both the type of infection as well as the existence of treatment options. Table xx outlines current treatment for each type of hepatitis.

Complications – Many cases of Hepatitis A, B and C are shed from the body and go away on their own. Chronic Hepatitis, particularly HBV and HCV, can persist in individuals with compromised immunity due to HIV/AIDS, heart disease, and diabetes. Hepatitis can lead to chronic liver damage in the form of cirrhosis and liver cancer. Chronic HBV and HCV are the leading cause of liver cancer and cirrhosis worldwide and in the US.

Prevention – Screening is available for acute HAV and acute and chronic HBV and HCV. Screening can detect the virus and be a catalyst to start the respective recommended treatment regime. The CDC recommends wide-scale screening for chronic HBV and HCV due to the asymptomatic nature of the virus. Primary prevention for hepatitis is through vaccination. Table 4 outlines the screening and vaccination recommendations from the CDC.

Table 4 The ABC’s of Hepatitis for Health Professionals (by the CDC has been designated to Public Domain)

Sterile Syringe Programs (SSPs)

Sterile Syringe Programs (SSPs) are prevention programs linked to substance abuse but also provide a range of services for communities such as treatment, testing, safe disposal options, and sterile injection supplies. There is a direct relationship between injection drug use and the transmission of blood borne illnesses such as HIV and hepatitis. This intervention is crucial to reduce the transmission in at risk communities.

Despite evidence that SSPs do not increase crime or drug use and are effective in reducing disease transmission (CDC), these programs face policies that make them illegal or so limited they are ineffective. 15 states explicitly do not allow for the operation of SSPs. Discover SSP laws here. Most notably, the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2016 bars the use of federal funds in supplying sterile syringes, the core component of SSPs. The Act states that:

SEC. 520. Notwithstanding any other provision of this Act, no funds appropriated in this Act shall be used to purchase sterile needles or syringes for the hypodermic injection of any illegal drug: Provided, That such limitation does not apply to the use of funds for elements of a program other than making such purchases if the relevant State or local health department, in consultation with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, determines that the State or local jurisdiction, as applicable, is experiencing, or is at risk for, a significant increase in hepatitis infections or an HIV outbreak due to injection drug use, and such program is operating in accordance with State and local law.

In December of 2021, the White House released a “Model Law” outlining how to propose and pass legislation to advance SSPs and other harm reduction services in a battle against the opioid crisis. This “Model Law” is very similar to the information the CDC has continued to disseminate following the institution of the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2016 to suggest best practices for launching these programs. Additionally, the Pew Charitable Trusts suggest 4 steps for state policy makers to make way for successful SSPs:

- Permit SSPs to be established and operate according to best practices

- Reduce participant interactions with law enforcement

- Fund SSPs to cover materials and operations costs, including the purchase of syringes

- Facilitate opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment by allocating state funds or federal grants so SSPs can provide buprenorphine, an FDA-approved drug for the treatment of OUD

Vaccination Controversy: Rooted in Fraudulent Science

Modern vaccines have shown to be highly effective means of primary prevention for many dangerous viral infections for nearly 200 years. Despite current vaccines being safe and effective scientific discoveries, an alternative viewpoint has emerged over the past 30 years that questions and condemns vaccination. So, what started this movement? The anti-vaccination article responsible for the start of vaccination controversy was a study published by former medical doctor (Note: Former. As a result of his fraudulent research practices, his credentials have since been removed) Andrew Wakefield used fraudulent research practices to imply a link between the MMR vaccine and increased risk of autism. Read the summary of the expose from the British Medical Journal here: https://www.bmj.com/content/342/bmj.c7452

VACCINE MANDATES

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic came struggles against mandates requiring masking and encouraging vaccination. Vaccinations mandates, however, are not new. The CDC recommends vaccinations for 16 diseases to protect children from potentially deadly illness. Each state sets legislations for which vaccinations are required for children to attend school and childcare. See all state statutes and exemptions here. The DTap, MMR, Polio, and Varicella vaccines are required in every state for all children enrolling in kindergarten. Vaccination efforts are crucial in preventing outbreaks of disease and have been effective in the near eradication of some.

Beginning 2022, 15% of the population remains unvaccinated against COVID-19. The U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey (HPS) reports that the two leadings reasons that individuals remain unvaccinated are that they are “concerned about possible side effects” (49.6%) and they “don’t trust COVID-19 vaccines” (42.4%). The third leading reason, and perhaps most specific to the COVID-19, is that unvaccinated individuals “don’t trust the government” (35.4%). The skepticism of the government is creating misplaced doubt in public health efforts, though mistrust in authority is not a new challenge for health care professionals.

In November of 2021, two policies took effect that covers two thirds of all workers under vaccination mandates. OSHA policy covers roughly 84 million employees and requires “employers with 100 or more employees to ensure each of their workers is fully vaccinated or tests for COVID-19 on at least a weekly basis” along with stipulations for time off to cover vaccination appointments and masking requires for unvaccinated individuals. Additionally, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) requires that the 17 million health care workers at facilities participating in Medicare and Medicaid are fully vaccinated. As the COVID-19 pandemic evolves it is likely that vaccination mandate policies will continue to as well.

recall quiz

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- Vaccination is a vital means of prevention for many of the infections discussed in this chapter. List and explain the recommended vaccination schedules for each infection for which a vaccine is available. Is vaccination a form of primary or secondary prevention?

- Describe secondary prevention for infectious mononucleosis and HAV, HBV, and HCV.

- As a public health professional, you are approached by a vaccination skeptic who subscribes to the myth that vaccinations lead to complications such as autism. How would you explain to this person the scientific literature that has de-bunked this myth?

references

Adams, D. P. (2021). Foundations of Infectious Disease: A Public Health Perspective. Jones & Bartlett.

American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). (n.d.) Recommendations for testing, management, and treating Hepatitis C: HCV testing and linkage to care. https://www.hcvguidelines.org/

American Cancer Society. (2019, April 1). Liver cancer risk factors. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/liver-cancer/causes-risks-prevention/risk-factors.html

Barraza, L., Schmit, C., & Hoss, A. (2017). The latest in vaccine policies: Selected issues in school vaccinations, healthcare worker vaccinations, and pharmacist vaccination authority laws. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 45(1_suppl), 16–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073110517703307

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016a). Program guidance for implementing certain components of syringe services programs, 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/cdc-hiv-syringe-exchange-services.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016b). The ABCs of Hepatitis. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/resources/professionals/pdfs/abctable.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018, August 27). People at high risk for flu complications. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/highrisk/index.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019a). Chickenpox. https://www.cdc.gov/chickenpox/about/symptoms.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019b). Hepatitis B questions and answers for health professionals. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hbv/hbvfaq.htm#overview

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019c). Hepatitis C questions and answers for health professionals. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hcv/hcvfaq.htm#section2

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019d). How flu spreads. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/disease/spread.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019e). Measles. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/symptoms/signs-symptoms.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019f). Recommended vaccines by age. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/vaccines-age.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019g). Shingles. https://www.cdc.gov/shingles/about/symptoms.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019h). Vaccination laws. https://www.cdc.gov/phlp/publications/topic/vaccinationlaws.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019i, March 12). Transmission of measles. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/transmission.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019j, June 13). Measles complications. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/symptoms/complications.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019k, July 8). Federal funding for syringe services programs. https://www.cdc.gov/ssp/ssp-funding.html#:~:text=Current%20federal%20law%20prohibits%20the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019l, August 2). Vaccine (shot) for chickenpox (varicella). https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/parents/diseases/varicella.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019m, September 10). Hepatitis A questions and answers for the public. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hav/afaq.htm#transmission

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019n, September 19). Prevent seasonal flu. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/prevent/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020a, October 27). Hepatitis B FAQs. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hbv/bfaq.htm#bFAQe02

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020b, November 4). Shingrix shingles vaccination: What you should know. Www.cdc.gov. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/shingles/public/shingrix/index.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fvaccines%2Fvpd%2Fshingles%2Fpublic%2Findex.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021a, May 17). Hepatitis C surveillance in the United States for 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2019surveillance/HepC.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021b, May 26). Hepatitis A surveillance in the United States for 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2019surveillance/HepA.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Leading causes of death. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm

Cleveland Clinic. (2015). Mononucleosis (mono). https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/13974-mononucleosis

Edlin, B. R., Eckhardt, B. J., Shu, M. A., Holmberg, S. D., & Swan, T. (2015). Toward a more accurate estimate of the prevalence of Hepatitis C in the United States. Hepatology, 62(5), 1353–1363. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.27978

Hamann, B. (2007). Disease: Identification, Prevention, and Control (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

Hepatitis B Foundation. (2019). Acute vs. chronic Hepatitis B infection. https://www.hepb.org/what-is-hepatitis-b/what-is-hepb/acute-vs-chronic/

Johns Hopkins Medicine. (2019). Infectious mononucleosis. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/infectious-mononucleosis

Johnson, J. (2021, February 23). Chickenpox party: Benefits, risks, and how to do it safely. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/323728

lappaadm, L. A. and P. P. A. (2021, December 7). Model syringe services program act. https://legislativeanalysis.org/model-syringe-services-program-act/

Lieberman, A., & Davis, C. (2021, February 5). Ensuring access to clean needles can save lives, but legal barriers persist. Network for Public Health Law. https://www.networkforphl.org/news-insights/ensuring-access-to-clean-needles-can-save-lives-but-legal-barriers-persist/

Mayo Clinic. (2018). Measles: Diagnosis and treatment. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/measles/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20374862

Mayo Clinic. (2021, November 1). Influenza (flu): symptoms and causes. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/flu/symptoms-causes/syc-20351719

Monte, L.M. (2021, December 28). Who are the adults not vaccinated against COVID? United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/12/who-are-the-adults-not-vaccinated-against-covid.html

National Academy for State Health Policy. (2022, July 11). State lawmakers submit bills to ban COVID-19 vaccine mandates and passports. https://www.nashp.org/state-lawmakers-submit-bills-to-ban-employer-vaccine-mandates/

National Conference of State Legislatures. (2022, May 25). States with religious and philosophical exemptions from school immunization requirements. https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/school-immunization-exemption-state-laws.aspx

Nobiling, B.D. & Petrolino, A.P. (2022). Reported self-efficacy of public health professionals during COVID-19. Poster session presented at the Society for Public Health Education Digital Conference. March 22-25, 2022.

Office of Infectious Disease and HIV/AIDS Policy (OIDP). (2016, April 20). Data and trends. https://www.hhs.gov/hepatitis/learn-about-viral-hepatitis/data-and-trends/index.html

Policy (OIDP), O. of I. D. and H. (2016, April 20). Policies and guidelines. https://www.hhs.gov/hepatitis/policies-and-guidelines/index.html

Ryerson, A. B., Schillie, S., & Barker, L. K. et al. (2020). Vital signs: Newly reported acute and chronic Hepatitis C cases: United States, 2009–2018. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(14), 399–404. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6914a2

The Pew Trust. (2021, March). Syringe distribution programs can improve public health during the opioid overdose crisis. https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2021/03/syringe_distribution_programs_can_improve_public_health.pdf

The Policy Surveillance Program. (2019, August 1). Syringe service program laws. https://lawatlas.org/datasets/syringe-services-programs-laws

Tosh, P. (2021, May 18). What’s the difference between H1N1 flu and influenza A? https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/swine-flu/expert-answers/influenza-a/faq-20058309

The White House. (2021, November 4). Fact sheet: Biden administration announces details of two major vaccination policies, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/11/04/fact-sheet-biden-administration-announces-details-of-two-major-vaccination-policies/

World Health Organization. (2019, December 5). Measles. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/measles

Sudden Acute Respiratory Syndrome

Severe inflammation of the brain.