3 Chapter 3: Bacterial Infections

Brandye Nobiling

Chapter Objectives:

- Differentiate among selected types of pneumonia.

- Identify bacterial infections by the route of transmission.

- Identify individuals most at risk for selected bacterial infections.

- Recognize types of staph infection.

- Explain primary and secondary means of prevention for selected bacterial infections.

- Explain recommended vaccination schedules for selected bacterial infections.

- Analyze when it is appropriate to use antibiotics to treat signs/symptoms of infection.

introduction

Bacteria are single-celled microorganisms that exist just about everywhere. Bacteria can be harmless, and some are even healthy. For example, our colon has healthy bacteria that helps maintain homeostasis. Harmless bacteria are found throughout our environment, and most of the time encountering these bacteria do not pose any harm. There are circumstances, however, where bacteria can make us sick. This chapter covers selected bacterial infections classified by means of transmission and by type of bacterium.

Respiratory bacterial infections

Pneumonia

Pneumonia is a lower respiratory infection that can be caused by several infectious agents including bacteria (e.g. Pneumococcal pneumonia), viruses (e.g. COVID-19) and fungi (e.g. Pneumocystis pneumonia). Pneumonia can also be classified with how a person acquired the infection. “Community-acquired pneumonia is when someone develops pneumonia in the community (not in a hospital). Healthcare-associated pneumonia is when someone develops pneumonia during or following a stay in a healthcare setting. Healthcare settings include hospitals, long-term care facilities, and dialysis centers. Ventilator-associated pneumonia is when someone gets pneumonia after being on a ventilator, a machine that supports breathing. The bacteria and viruses that most commonly cause pneumonia in the community are different from those in healthcare settings,” (CDC, 2020, para. 4).

Pneumococcal, mycoplasma and Legionnaires’ disease are all caused by bacteria.

Pneumococcal pneumonia

Pneumococcal pneumonia is any type of pneumonia caused by the Streptococcus pneumoniae bacterium and is the most common type of pneumonia.

Individuals at risk – This type of pneumonia is most likely to occur in people on either side of the age spectrum (i.e., those who are young or those 65 years of age and older), people with compromised immunity due to co-morbidities or malnutrition, people who smoke tobacco, and people who abuse alcohol.

Signs/Symptoms – According to Johns Hopkins Medicine, the following are common symptoms of pneumococcal pneumonia:

- Bluish color to lips and fingernails

- Confused mental state or delirium, especially in older people

- Cough that produces green, yellow, or bloody mucus

- Fever

- Heavy sweating

- Loss of appetite

- Low energy and extreme tiredness

- Rapid breathing

- Rapid pulse

- Shaking chills

- Sharp or stabbing chest pain that’s worse with deep breathing or coughing

- Shortness of breath that gets worse with activity

Johns Hopkins Medicine, 2020, para. 4).

Transmission – This bacterium is spread from person to person with direct contact with respiratory droplets from the nose or mouth.

Treatment – Antibiotics are the primary means for treating pneumococcal pneumonia. However, research shows an increased resistance to several types of antibiotics. This underscores the importance of prevention through vaccination.

Complications – Pneumococcal pneumonia can often lead to serious complications or even death in at-risk individuals. Although pneumonia is no longer the leading cause of death in the United States like it was in 1900, pneumonia is still a cause of death of at-risk individuals (young children, adults 65 and older, and the immunocompromised).

Prevention – Vaccines are available for pneumococcal pneumonia. Currently there are two vaccines, each one approved for a particular age group (i.e. children and adults 65 and older). “CDC recommends pneumococcal vaccination for all children younger than 2 years old and all adults 65 years or older. In certain situations, older children and other adults should also get pneumococcal vaccines,” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020, para. 2). People are urged to discuss this vaccine with their healthcare provider.

Mycoplasma pneumonia

Mycoplasma pneumonia is caused by the bacterium of the same name (Mycoplasma pneumoniae) and produces less serious symptoms than pneumococcal or Legionnaires’ disease. Mycoplasm pneumonia is often referred to as “walking pneumonia” in adults or a “chest cold” in children. There currently is no vaccination for this type of pneumonia.

Individuals most at risk – Mycoplasma pneumonia spreads rapidly in crowded environments. Therefore, those most at risk are students and staff in schools, college/university residence halls, nursing homes, hospitals, military barracks, and high-rise housing.

Signs/Symptoms – Common symptoms of a chest cold include sore throat, fatigue, fever, lingering cough, and headache. Common symptoms of “walking pneumonia” include fatigue, a productive cough, fever, shortness of breath, and chest pain

Transmission – “When someone infected with M. pneumoniae coughs or sneezes, they create small respiratory droplets that contain the bacteria. Other people can get infected if they breathe in those droplets. Most people who spend a short amount of time with someone who is sick with M. pneumoniae do not get infected. However, the bacteria often spread between people who live together since they spend a lot of time together.” (CDC, 2020, para. 3)

Treatment – While most cases are mild and may not require medication, antibiotics can be prescribed if needed.

Complications – Although uncommon, mycoplasma pneumonia can progress to additional respiratory issues, encephalitis, and kidney problems.

Prevention – Because a vaccine is not available of this type of pneumonia, practicing good hygiene is the most effective way to prevent the spread of mycoplasma pneumonia. This includes proper hand-washing or using an alcohol-based hand sanitizer if hand-washing isn’t possible, coughing/sneezing in the bend of your arm (i.e., the “vampire sneeze”) instead of in the palm of your hand.

Legionnaires’ disease

Legionnaires’ disease was not discovered until 1976 when a group of individuals attending the American Legion Convention that year in Philadelphia contracted the infection and started showing symptoms.

Individuals at risk – Most people exposed to Legionnaires’ disease do not get sick. Individuals most likely to experience symptoms and complications of this infection have the same characteristics as those most at risk for contracting pneumococcal pneumonia, young children, adults 65 years of age and older, people with compromised immunity due to co-morbidities or malnutrition, people who have a weakened immune system due to recent surgeries, and people who smoke tobacco.

Signs/Symptoms – Legionnaires’ disease produces similar symptoms as mycoplasma pneumonia, including fatigue, cough, fever, shortness of breath, and chest pain

Transmission – Unlike the other two types of bacterial pneumonia, Legionnaires’ disease is not spread from person to person. According to the CDC “Legionella bacteria are found naturally in freshwater environments, like lakes and streams. The bacteria can become a health concern when they grow and spread in human-made building water systems like

- Shower heads and sink faucets

- Cooling towers (structures that contain water and a fan as part of centralized air cooling systems for buildings or industrial processes)

- Hot tubs

- Decorative fountains and water features

- Hot water tanks and heaters

- Large, complex plumbing systems

Home and car air-conditioning units do not use water to cool the air, so they are not a risk for Legionella growth,” (CDC, 2021,para. 1)

Treatment – Like pneumococcal pneumonia, Legionnaires’ disease is primarily treated with antibiotics.

Complications – Like pneumococcal pneumonia, Legionnaires’ disease can cause serious, even deadly, complications in at-risk individuals. According to the CDC, “About 1 out of every 10 people who gets sick with Legionnaires’ disease will die due to complications from their illness.” (CDC, 2021, para. 4).

Prevention – Due to how different this disease spreads compared to the other types of pneumonia; prevention efforts are also different. There is no vaccine for Legionnaires’ disease. Prevention is focused on programs ensuring the cleanliness of the types of water systems mentioned above that can spread the bacterium. Most of these programs are targeted on building managers. Individuals who have personal hot tubs, however, also need to follow safety protocol to ensure they are not growing Legionella.

Pertussis (whooping cough)

Pertussis is a lower respiratory infection caused by the bacterium Bordetella pertussis and is highly contagious, especially in babies and young children. A cardinal symptom of pertussis is the presence of a whoop-like coughing sound when the person is gasping for air.

Individuals at risk – Pertussis is a highly contagious infection, so anyone can possibly at risk of contracting it, especially if they are not up to date on their Tdap vaccination. Babies under one year of age are most at risk of serious complications from pertussis. Pregnant women in their third trimester are also considered high risk because they could transmit the infection to their newborn. Vaccination recommendations are discussed under “prevention”.

Signs/Symptoms – Pertussis symptoms are often broken down by phase. The first phase, referred to as Catarrhal, is described as when symptoms first appear after an incubation period of about one week after exposure. Symptoms of the catarrhal stage may include irritating cough (but not yet the whooping cough as that develops in a later stage), sneezing, runny nose, and low-grade fever. Babies may experience apnea, which is a short pause in breathing. These symptoms mimic the common cold and are therefore often ignored or treated with over-the-counter (OTC) medication. Antibiotic therapy may not occur if it’s suspected to be a common and mild viral infection like a cold. If pertussis is not properly treated at this stage it will progress into the second stage, the Paroxysmal stage. It’s in this stage that the eminent symptom of the “whooping” cough sets in. In addition to the gasping cough, individuals my expel mucous, have nose bleeds, vomit, or be at higher risk of a hernia or detached retina due to the forcible nature of the whooping cough. Antibiotic therapy is still viable treatment in this stage, but symptoms may still linger for several weeks. Finally, the third stage, called the convalescent stage, is when the body is recovering from the infection. During this time the individual may continue the whooping cough, especially if triggered again by an upper respiratory infection.

Transmission – Pertussis spreads from person to person through coughing, sneezing, or being in close contact with an infected person. The latter situation is common in asymptomatic adults who may pass the infection to an infant.

Treatment – Treatment for pertussis depends on the stage at the time of diagnosis and the age and other characteristics of the patient. Antibiotic/antimicrobial treatment is typically the first line of defense. Click here to read about the varied treatments for pertussis.

Complications – Infants and those who are unvaccinated are most at risk for complications from pertussis. According to the CDC, “About half of babies younger than 1 year old who get pertussis need care in the hospital. The younger the baby, the more likely they will need treatment in the hospital,” (CDC, 2017 para. 3). The most common complications in babies are apnea and pneumonia or another lung infection. Hospitalization of teens or adults who have pertussis is significantly less common (less than 5% need hospitalization). Complications in teens and adults are usually effects of the intense coughing fits.

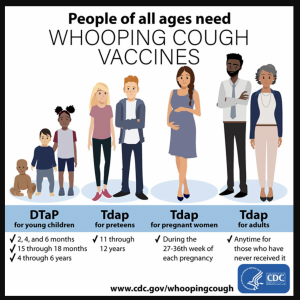

Prevention – The primary means of preventing pertussis is vaccination. The DTaP vaccine is recommended for infants starting at 2 months and periodic boosters recommended through 6 years of age. After that, the Tdap vaccine is recommended starting in the pre-teens with boosters recommended periodically throughout adulthood. As started earlier, pregnant women in their third trimester are highly recommended to get their Tdap vaccination. Figure 3.1 outlines the CDC’s Tdap recommendations.

Tuberculosis (TB)

TB is a lower respiratory infection caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis. While it is not a significant public health crisis in the United States, it is in many countries in the world. About 95% of all TB illnesses and deaths are in developing countries. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), “eight countries account for two thirds of the total, with India leading the count, followed by China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Pakistan, Nigeria, Bangladesh and South Africa,” (WHO, 2021, paras. 4, 18).

Individuals at risk – People living in high-risk countries, including the eight mentioned above are more susceptible to contracting TB. Other risk factors include having HIV, alcohol use disorder, and diabetes mellitus; living in poverty; being malnourished; and being exposed to silica in the workplace. It should be noted that although the majority of the TB cases occur in a finite number of countries, the fact that we live in a globally-connected world through air travel means that anyone could be exposed to TB despite country of residence.

Signs/Symptoms – Symptoms of TB are dependent upon which part of the body is affected. Once someone is infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the bacterium can target one or more organs. Pulmonary TB, however, is the most common type of infection, and can be diagnosed as active or latent, with latent being more common. Approximately 90% of individuals infected have latent TB. Individuals with latent TB are asymptomatic and are not contagious. But if they do start experiencing symptoms of TB, they become active TB patients. Symptoms of active TB include a lingering cough that lasts for several weeks, fever, chills, and loss of appetite.

Transmission – TB is spread through direct contact with respiratory droplets when someone sneezes or coughs or contact with saliva.

Treatment – No treatment is needed for cases of latent TB. In cases of active TB, the course of treatment is a 6-month regimen of antimicrobial medication, including the long-trusted and effective antibiotics, isoniazid and rifampicin. A current public health crisis is the persistence of drug-resistant TB. In these cases, additional treatment is needed. The caveats, however, are getting people diagnosed with Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) access to proper treatment as well as the longer treatment period for cases of MDR-TB.

Prevention – The first line of prevention in the United States is screening for TB. According to the CDC, “There are two kinds of tests that are used to detect TB bacteria in the body: the TB skin test (TST) and TB blood tests. A positive TB skin test or TB blood test only tells that a person has been infected with TB bacteria. It does not tell whether the person has latent TB infection (LTBI) or has progressed to TB disease. “Other tests, such as a chest x-ray and a sample of sputum, are needed to see whether the person has TB disease,” (CDC, 2016, para. 1). If someone tests positive, additional tests are needed to determine if that person has active or latent TB, especially of no symptoms are present. So, who should get tested? Anyone who has spent time in high-risk countries; works in healthcare facilities, schools, correctional facilities, or other sites where there is interaction with a large volume of people; those who may have been exposed to TB. Many job sites may require regular TB tests to start or continue working there. Globally, the Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine exists and is often given to infants and children in at-risk countries.

Gastrointestinal bacterial infections

The majority of gastrointestinal (GI) infections are linked to foodborne illnesses and are discussed in Chapter 6. The only common bacterial infection affecting the GI tract not associated with FBI that is covered in this chapter is Clostridium difficile.

Clostridium difficile

Clostridium difficile is an infection of the GI tract caused by the bacterium Clostridium difficile which is a healthy bacterium present in the GI tract. When an individual undergoes long-term antibiotic therapy, however, the normal bacterial flora in the GI tract gets interrupted leading to the overgrowth of Clostridium difficile, resulting in an infection in the large intestine (i.e. colon). The CDC estimates there are about 500,000 cases of C. difficile infection each year.

Individuals at risk – Patients at the greatest risk of Clostridium difficile infection are those who are immunocompromised, have been in health-care settings for extended periods, are older, have recently taken antibiotics, have had gastrointestinal procedures done, or use proton pump inhibitors, which reduce stomach acidity and allow proliferation of C. difficile. Because this species can form endospores, it can survive for extended periods of time in the environment under harsh conditions and is a considerable concern in health-care settings.

Signs/Symptoms – Symptoms of C. difficile include severe diarrhea, stomach pain, nausea, loss of appetite, and fever.

Transmission – C. difficile can spread from person-to-person via the oral-fecal route with direct contact with feces or a surface contaminated with the bacterium. C. difficile can also live on the skin and can spread to another person if they touch the skin of an infected person.

Treatment – The first step is to stop antibiotic use (if antibiotics are the cause of the infection), and then to provide supportive therapy with electrolyte replacement and fluids. An antibiotic called Metronidazole is the preferred treatment if the C. difficile diagnosis has been confirmed. Vancomycin can be an alternative antibiotic choice for patients who don’t respond positively to metronidazole or those who are allergic and for individuals under 10 years of age or women who are pregnant.

Complications – Individuals age 65 and over who are currently or recently have been hospital patients or long-term care facility residents are most at risk for complications of C. difficile. Serious complications include severe dehydration, kidney failure, severely enlarged colon (referred to as megacolon), and even death.

Prevention – Preventing the spread of C. difficile is possible by maintaining sanitary conditions such as proper hand washing, showering, and disinfecting surfaces. Due to the frequency of transmission in healthcare and long-term care facilities, education on how to prevent the spread of C. difficile is vital.

Skin and other bacterial infections

The remaining bacterial infections discussed in this chapter affect the skin, hair, bones, and mucosa of the body. The majority of these infections are caused by the following bacteria: Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, Haemophilus influenzae, and Neisseria meningitidis.

A large number of infections are caused by the bacterium Staphylococcus aureus, often referred to simply as “staph” infections. Staph is commonly found in and on our bodies and usually does not pose a threat unless it enters the body through a cut or abrasion. Staph infection is the cause of boils, folliculitis, impetigo, osteomyelitis, endocarditis, and toxic shock syndrome.

Staph Infections

Boils

Boils are the most common type of staph infection. They are also called furuncles, and are typically a 1-5 cm nodule filled with pus that develops in an oil or sweat gland. They most commonly occur on the neck, face, armpits, waist, groin, thighs, or buttocks. Depending on how deep the infection, it can be less severe called folliculitis (infection of a hair follicle) or more severe called a carbuncle in which multiple follicles are infected.

Individuals at risk – because staph commonly lives on the skin, anyone can develop boils or folliculitis. Factors that may increase risk include having uncontrolled diabetes, a weak immune system, have skin injuries or infections, and have gotten an intravenous (IV) injection.

Signs/Symptoms – The presence of the pus-filled nodule is the primary symptom. The nodule can be painful and can increase in size over time if not treated. The more severe the infections, like in the case of carbuncles, more systemic (i.e. widespread) symptoms like fever and fatigue are possible.

Transmission – The nodule itself cannot “spread” but the infection can through contact with the nodule and especially the pus from the nodule. The staph infection can spread from one part of the body to another through self-infection. It can also be passed to others via direct contact, sharing razors or towels, and in hot tubs.

Treatment – Antibiotic therapy typically is not the first line of treatment for folliculitis, boils, or carbuncles. Non-pharmaceutical treatments such as warm compresses and promoting natural drainage of the nodule are recommended first. That said, however, one should not try and squeeze the boil themselves. That will promote further spread. If these are unsuccessful, health care providers can prescribe topical antibiotics, oral antibiotics (if necessary), and may need to cut and drain the nodule.

Complications – In severe and untreated cases the staph infection can spread to other parts of the body including the blood.

Prevention – Primary prevention of staph infection includes practicing sanitary methods. Fresh wounds should be covered. If left uncovered wounds can become a portal of entry for infection. Proper hand washing at all times, especially after visiting a hospital can prevent staph infection. Also, avoid sharing personal items such as razors, sheets, clothes, athletic equipment, and towels. Secondary prevention includes not squeezing the nodule to drain yourself, washing hands after touching the nodule, and cleaning any item that may have come into contact with the nodule.

Impetigo

Impetigo is a bacterial infection of the skin typically around the nose and mouth and very common in infants and young children. It is either caused by Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus pyogenes.

Individuals at risk – Infants and young children, especially those who regularly attend daycare or school, are most at risk for impetigo. Adults can also get impetigo if they are exposed to crowds, have scabies , live in tropical climates, or practice poor hygiene.

Signs/Symptoms – The presence of the rash-like, clustery sores is the primary symptom of impetigo. These sores initially are red then turn yellow and become crusty.

Transmission – Transmission of impetigo is the same as folliculitis, and spreads with direct contact with the sores or the pus/fluid from the sores. Because impetigo is highly contagious, day care centers, schools, and some worksites may have a policy in place that requires someone to have to stay home until treatment has started.

Treatment – Topical or oral antibiotics are used to treat impetigo.

Complications – Complications are rare with impetigo. Untreated impetigo can lead to kidney problems a few weeks after the rash goes away.

Prevention – Impetigo is prevented the same way as folliculitis with proper wound care and hygiene. Education in day care centers and schools on the facts and means of prevention of impetigo can be helpful.

Osteomyelitis

Osteomyelitis is a bacterial infection usually caused by a staph infection that spread to the bones or bone marrow. Typically, long bones, such as the femur or humus, are affected, but osteomyelitis can infect any bone in the body.

Individuals at risk – Osteomyelitis is more common in children than adults and more in boys than girls. Other risk factors include using IV drugs, recently having surgery, having a compromised immune system, and practicing poor hygiene.

Signs/Symptoms – Symptoms of osteomyelitis include cardinal signs of inflammation (i.e. pain, swelling, redness, and heat) on the area of infection as well as fever and fatigue.

Transmission – Osteomyelitis is caused by a staph infection (such as a boil or infected wound) spreading to the bone or bone marrow due to improper treatment or care. Osteomyelitis can also happen if one is exposed to staph infection during surgery.

Treatment – Treatment will depend on many factors, such as the age and health of the person affected, but typically involves initial hospitalization during which the patient received antibiotics through an IV, followed by oral antibiotic therapy once discharged from the hospital. Surgery to repair or remove damaged bone may be necessary.

Complications – According to the Mayo Clinic, the following are possible complications of osteomyelitis:

- Bone death (osteonecrosis). An infection in your bone can impede blood circulation within the bone, leading to bone death. Areas where bone has died need to be surgically removed for antibiotics to be effective.

- Septic arthritis. Sometimes, infection within bones can spread into a nearby joint.

- Impaired growth. Normal growth in bones or joints in children may be affected if osteomyelitis occurs in the softer areas, called growth plates, at either end of the long bones of the arms and legs.

- Skin cancer. If your osteomyelitis has resulted in an open sore that is draining pus, the surrounding skin is at higher risk of developing squamous cell cancer. (Mayo Clinic, n.d., para. 16).

Prevention – Osteomyelitis can be prevented in the same way the other infections discussed in this section can be prevented, through proper wound care and hygiene. Transmission during surgery can be prevented by hospital staff following sanitary protocol.

Endocarditis

Endocarditis is an infection of the inner lining of the chambers of the heart. It is commonly caused when either Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus pyogenes (“strep”) spread to the heart from another part of the body. Endocarditis can be a complication of a more superficial staph or strep infection (e.g., boil) that spreads to the lining of the heart.

Individuals at risk – People most at risk of endocarditis are those with heart conditions such as heart valve problems or who have an artificial heart device, like a pacemaker. Risk increases with age. Other risk factors include having poor dental health and using IV drugs because the puncture wound from the needle can become infected and that infection can spread to other parts of the body, such as the heart.

Signs/Symptoms – According to the Mayo Clinic the following are possible signs/symptoms of endocarditis:

Common signs and symptoms of endocarditis include:

- Aching joints and muscles

- Chest pain when you breathe

- Fatigue

- Flu-like symptoms, such as fever and chills

- Night sweats

- Shortness of breath

- Swelling in your feet, legs or abdomen

- A new or changed heart murmur, which is the heart sound made by blood rushing through your heart (Mayo Clinic, 2020, para. 4)

Transmission – Endocarditis is the result of the bacterium spreading to the heart from another part of the body. For example, if someone has highly infected gums and brushes their teeth, the bacteria can spread from the gums into the bloodstream and eventually the heart. It can also spread from an infected skin wound or boil to the heart.

Treatment – Similar to osteomyelitis, intense IV antibiotic therapy is often the first step in treatment, followed by an oral antibiotic regimen upon discharge from the hospital. Surgery to repair damage heart tissue may also be needed.

Complications – Endocarditis can cause other heart problems, stroke, blood clots, and kidney damage.

Prevention – The best way to prevent endocarditis is to properly take care of your dental health by flossing and brushing teeth daily as well as getting regular dental checkups. Proper wound care and treatment of any skin infection is also vital to prevent infection from spreading to other parts of the body.

Toxic shock syndrome (TSS )

TSS from staph infections were first recognized in the late 1970s and later the incidence rate increased in the early 1980s as high absorbency tampon users became increasing ill. According to the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), “In 1980, 890 cases of TSS were reported, 812 (91%) of which were associated with menstruation…” and 5% of women with menstrual TSS died.

Beginning in the 1980s, under Section §801.403 of the Code of Federal Regulations, the FDA enforced that there be an alert statement warning users of the risk of TSS, the inclusions of the signs and symptoms of TSS, and a guide to tampon absorbency to instruct users how to choose the correct tampon to reduce the risk of TSS.

There is no question that this is related to the significant decline in menstrual TSS cases. By 1989, “61 cases of TSS were reported, 45 (74%) of which were menstrual,” and there were no deaths reported of women with menstrual TSS. Today, the incidence of TSS is 1 to 17 per 100,000 menstruating women and girls per year.

What’s my risk for TSS?

Rates of staph infection linked to over-absorbent tampons peaked over 40 years ago. Even though the tampons today are not the same as those in 1980, there is still a lingering worry about getting TSS from tampon use. Click here to read an article about the current risk of staph TSS.

Other Bacterial Infections

Conjunctivitis

Conjunctivitis also known as “pink eye” is an infection of or irritation to the conjunctiva, the outermost lining of the eye and eye lid. Conjunctivitis is caused by staph, strep,

Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, or, less commonly, Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae bacteria; viruses; and allergies or other irritants. This chapter is focused on the bacterial types of conjunctivitis.

Individuals at risk – Conjunctivitis is a highly contagious infection. It is more common in children during winter and early spring. According to the CDC, conjunctivitis is responsible for children collectively missing 3 million days of public school each year.

Signs/Symptoms – Pinkness of the eye, itching and burning of the eye, swelling of the eye, and discharge from the eye are common indications of conjunctivitis. In bacterial types of conjunctivitis, this discharge can cause the eyelids to stick together especially first thing in the morning upon waking.

Transmission – Conjunctivitis is very contagious. It can spread upon direct contact with an infected person through skin-to-skin contact or respiratory droplets or by contact with a contaminated object or surface.

Treatment – Bacterial conjunctivitis can clear on its own without medication in many cases. Based on the presence of certain symptoms, however, antibiotics may be prescribed to speed up healing and reduce discomfort.

Complications – Bacterial conjunctivitis can have serious complications in newborns, especially those caused by chlamydia or gonorrhea. This can lead to serious eye problems and even blindness in the newborn.

Prevention – Most cases of bacterial conjunctivitis can be prevented with proper handwashing, avoidance of touching the eyes with unwashed hands, and not sharing personal items with others.

Meningitis

Meningitis is an inflammation of the meninges, the layers of membrane tissue surrounding the brain and spinal cord. Meningitis can be caused by bacteria caused by strep, Haemophilus influenzae, Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli, or Neisseria meningitidis; a virus, or a fungus. This chapter focuses on bacterial meningitis. According to the Cleveland Clinic, “Acute bacterial meningitis is the most common form of meningitis. Approximately 80 percent of all cases are acute bacterial meningitis. Bacterial meningitis can be life threatening,” (2019, para. 3).

Individuals at risk – Bacterial meningitis is contagious and can spread quickly in crowded places such as college residence halls and military barracks. Children under the age of two are at high risk, so are people with compromised immunity, and individuals who recently underwent spinal surgery.

Signs/Symptoms – Symptoms of acute bacterial meningitis occur quickly after exposure and include fever, headache, nausea, vomiting, sensitivity to light, confusion, and extreme stiffness of the neck. The latter symptom can be the tell-tell indication of meningitis.

Transmission – Transmission of meningitis depends on the bacterium that causes it. According to the CDC, here are the most common ways each type of bacterial meningitis spreads:

- Group B Streptococcus and E. coli: Mothers can pass these bacteria to their babies during birth.

- H. influenzae, M. tuberculosis, and S. pneumoniae: People spread these bacteria by coughing or sneezing while in close contact with others, who breathe in the bacteria.

- N. meningitidis: People spread these bacteria by sharing respiratory or throat secretions (saliva or spit). This typically occurs during close (coughing or kissing) or lengthy (living together) contact.

- E. coli: People can get these bacteria by eating food prepared by people who did not wash their hands well after using the toilet. (CDC, n.d. para. 8).

Treatment – Antibiotics are used to treat bacterial meningitis. To prevent serious complications, antibiotic therapy should be started immediately after symptoms appear or if one has been exposed to someone who has been diagnosed with bacterial meningitis.

Complications – Complications of meningitis can be serious and include paralysis, stroke, and even death.

Prevention – As a primary means of prevention, vaccines are available for strains caused by strep, Haemophilus influenzae, and Neisseria meningitidis bacteria. The CDC recommends pre-teens and anyone at risk receive a vaccine and booster if needed. Other forms of prevention include proper hand washing and hygiene, and screening for bacterial meningitis in pregnant women.

Proper antibiotic use

Because the conditions discussed in this chapter are caused by bacterial agents, it is important to know how to properly treat these infections. Part of properly treating bacterial conditions is correct antibiotic use. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has developed and implemented several campaigns to educate the public on proper antibiotic use in an attempt to reduce antibiotic resistance. Antibiotic resistance is considered to be a leading public health concern today. Click here to learn more about proper antibiotic use.

Recall Quiz

discussion questions

- List all of the infections discussed in this chapter for which there is a vaccine.

- Which infections discussed in this chapter typically do not need antibiotic therapy?

- Explain the recommended vaccine schedule for Tdap.

References

Adams, D. P. (2021). Foundations of Infectious Disease: A Public Health Perspective. Jones & Bartlett.

American Lung Association. (2020, March 9). Tuberculosis symptoms and diagnosis. https://www.lung.org/lung-health-diseases/lung-disease-lookup/tuberculosis/symptoms-diagnosis

Cedars Sinai. (n.d.). Folliculitis, boils, and carbuncles. Retrieved September 29, 2022, from https://www.cedars-sinai.org/health-library/diseases-and-conditions/f/folliculitis-boils-and-carbuncles.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Tuberculosis (TB) disease: Only the tip of the iceberg [infographic]. https://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/infographic/pdf/high-resolution-poster-tuberculosis-disease-only-the-tip-of-the-iceberg-11×17.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1990, June 29). Historical perspectives reduced incidence of menstrual Toxic-Shock Syndrome — United States, 1980-1990. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00001651.htm#:~:text=After%20the%20association%20between%20TSS

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019a). Bacterial Meningitis. https://www.cdc.gov/meningitis/bacterial.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019b). Legionnaires disease history and patterns. https://www.cdc.gov/legionella/about/history.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019c). Mycoplasma pneumoniae. https://www.cdc.gov/pneumonia/atypical/mycoplasma/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019d). Pneumococcal Disease. https://www.cdc.gov/pneumococcal/about/diagnosis-treatment.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019e). Pneumococcal vaccination. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/pneumo/public/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019f). Prevention of Legionnaires Disease. https://www.cdc.gov/legionella/about/prevention.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019g). Tuberculosis: Who should be tested. https://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/testing/whobetested.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019h, January 4). Conjunctivitis. https://www.cdc.gov/conjunctivitis/about/causes.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019i, January 4). What is C. diff? https://www.cdc.gov/cdiff/what-is.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019j, February 14). Pertussis (whooping cough) complications. https://www.cdc.gov/pertussis/about/complications.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019k, November 4). Prevent the spread of C. diff. https://www.cdc.gov/cdiff/prevent.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, May 29). Impetigo: All you need to know. https://www.cdc.gov/groupastrep/diseases-public/impetigo.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, March 25). Legionella (Legionnaires’ Disease and Pontiac Fever).

Dooling, K. L., & Toews, K. (2015). Active bacterial core surveillance for Legionellosis — United States, 2011–2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), 64(42), 1190–1193. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6442a2.htm

Gathers, R. (2022, March 16). Is folliculitis contagious? Types, causes, and prevention. https://www.healthline.com/health/is-folliculitis-contagious#spreading-through-touch

Hamann, B. (2007). Disease: Identification, Prevention, and Control (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

John Hopkins Medicine. (2019). Pneumonia. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/pneumonia

Mayo Clinic. (2020a, May 6). Staph infections – Symptoms and causes. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/staph-infections/symptoms-causes/syc-20356221

Mayo Clinic. (2020b, November 14). Endocarditis – symptoms and causes. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/endocarditis/symptoms-causes/syc-20352576

Mayo Clinic. (2020c, November 14). Osteomyelitis – symptoms and causes. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/osteomyelitis/symptoms-causes/syc-20375913

Mayo Clinic. (2021a, August 27). C. difficile infection – Symptoms and causes. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/c-difficile/symptoms-causes/syc-20351691

Mayo Clinic. (2021b, August 27). C. difficile infection -symptoms and causes. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/c-difficile/symptoms-causes/syc-20351691

Mayo Clinic. (2021c, September 18). Boils and carbuncles – diagnosis and treatment. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/boils-and-carbuncles/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20353776

Minnesota Department of Health. (n.d.). Clostridioides (Clostridium) Difficile Clinical Information – Minnesota Dept. of Health. Www.health.state.mn.us. Retrieved September 29, 2022, from https://www.health.state.mn.us/diseases/cdiff/hcp/clinical.html

National Archives. (2021). User labeling for menstrual tampons. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/chapter-I/subchapter-H/part-801/subpart-H/section-801.430

Nemours Teens Health. (2018). Osteomyelitis (for teens). https://kidshealth.org/en/teens/osteomyelitis.html

New York University Langone Health. (n.d.). Preventing Staphylococcal Infections. https://nyulangone.org/conditions/staphylococcal-infections/prevention

NHS. (2020). Causes: Endocarditis. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/endocarditis/causes/

Nova Scotia Health Authority. (2020). Eye infections in newborns caused by gonorrhea and chlamydia. https://www.nshealth.ca/sites/nshealth.ca/files/patientinformation/2050.pdf

OpenStax. (2019). Bacterial infections of the gastrointestinal tract. Open.oregonstate.education. https://open.oregonstate.education/microbiology/chapter/24-3bacterial-infections-of-the-gastrointestinal-tract/

The New York Times. (1982, June 22). U.S. sets new rules for warning labels on tampon boxes. https://www.nytimes.com/1982/06/22/us/us-sets-new-rules-for-warning-labels-on-tampon-boxes.html

The New York Times. (1988, September 24). F.D.A. is seeking to standardize ratings on tampon absorbency. https://www.nytimes.com/1988/09/24/us/fda-is-seeking-to-standardize-ratings-on-tampon-absorbency.html

University of Rochester Medical Center. (n.d.). Folliculitis, Boils, and Carbuncles – Health Encyclopedia – University of Rochester Medical Center. https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/encyclopedia/content.aspx?contenttypeid=85&contentid=p00285

University of Washington Medicine. (2018, March 7). Toxic Shock Syndrome is rare. Here’s what tampon users should know. Right as Rain by UW Medicine. https://rightasrain.uwmedicine.org/well/health/toxic-shock-syndrome-rare-heres-what-tampon-users-should-know

World Health Organization. (2021, October 14). Tuberculosis. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis