1 Chapter 1: History of Disease

Brandye Nobiling

Chapter Objectives

- Recall significant people and events that led to better understanding of infectious disease.

- Identify infectious disease epidemics throughout human history.

- Comprehend the paradigm shift from infectious disease to chronic disease in the historical timeline.

- Recognize events that were significant to the history of public health in the United States.

Introduction

Before we can start categorizing different types of chronic and infectious diseases, we need some background in terms of disease identification, control, management, and prevention which is a very important thing for public health educators. We need to know how far we’ve come and learn from history in order to know where to go in the future.

Selected Notable People, Places, and Events in Disease History

Ancient Civilizations

Ancient civilizations, like the Egyptians and Chinese, used the supernatural theory to guide their actions regarding disease and death. There was also a lack of well-researched and developed treatments, leading to the use of herbs and potions to “cure” or “treat” many ailments.

Documents reveal that even though the supernatural theory was prevalent at this time, natural causes were at least acknowledged. For example, the Old Testament accurately links the plague to rats as well as the separation of lepers from the general population (i.e. quarantining).

Hippocrates

Hippocrates, the ancient Greek physician, is considered the father of medicine. He was such an important figure in the history of disease treatment the Hippocratic Oath was developed in his name and rooted in his philosophy of practice. Physicians take the Hippocratic Oath as part of their professional preparation.

During his time, Hippocrates did extensive research on anatomy and physiology, but none of which were on human cadavers (that doesn’t occur until the Renaissance), which had its limitations. For example, one of his theories (that has since been debunked) was that the body had four different fluids that he termed humors.

Despite the inaccuracies, what Hippocrates was getting at is that these fluids are important for overall health and balance. If there was an off-balance, if one lost too much of one humor, then that could cause severe problems and lead to disease and possibly death. Practices to help restore balance among the humors like bloodletting were practiced, using leeches to pull blood out, and that actually was practiced for quite some time. Through Hippocrates’ studies, there became a connection between disease occurrence and natural and environmental influences.

Ancient Romans

Ancient Romans made significant public health contributions. One of the biggest advancements was the installation of aqueducts. These aqueducts were built to carry pure water to cities and provide a separation between drinking water and sewage water, thereby decreasing the risk of things like dysentery when people consume contaminated water or food

Sewers were installed to prevent the spread of infectious disease. Street cleaning was implemented. Public and private baths usually were available. A scientist, Varro, theorized that there are tiny creatures invisible to the eye that cause disease centuries before the microscope was invented (more on that later).

Galen

Galen is considered the founder of experimental physiology in that he did a number of dissections and research (but again, he didn’t use human cadavers). He was the leading physician to the Roman Empire, so he was an influential person. Because of his position, the misconceptions or the inaccuracies he found endured for a long time. It took a long time for other scientists in the future to come out, do their research, and have them take the place of the misconceptions that Galen laid the foundation for.

Ancient Christians, Muslims, and Religious Travels

Then there was a change in power, historically. The fall of the Roman Empire led to this next era that focused on religion and religious travels. Early Christian beliefs didn’t approve of the Greco-Roman emphasis on physical health and beauty and self-indulgence. Spirituality was the forefront, and anything that took time away from prayer and spiritual practice was seen in a negative light.

Just as the people involved in Muslim pilgrimages to Mecca, the Christian Crusades, and various explorations for new land (e.g. Columbus coming to North America) were traveling to new places so were infectious diseases, such as cholera and syphilis.

Documentation supports that these diseases spread to areas where they were nonexistent. If these diseases are nonexistent, the people who live in that place aren’t going to have developed immunity to fight them if exposed.

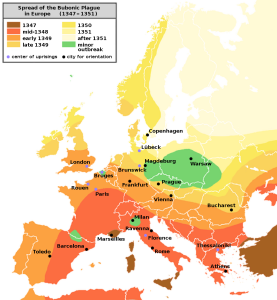

The Bubonic Plague

The increase global mobility is also linked to one of the most notorious infectious diseases in history, the bubonic plague (aka the “black death”) The bubonic plague killed two-thirds of the European population in the 1300’s. It is a bacterial infection that still exists today, but does not have the mortality rate it did in the Medieval times thanks to our advancements in prevention and control (most cases are linked to fleas from sick rodents, primarily).

Renaissance

The era of the Renaissance was full of innovation, and health science was no exception. Notable individuals, Vesalius and Leonardo Da Vinci were among the first to dissect human cadavers (it is estimated that Leonardo dissected about 30 human cadavers) from which they created sketches of human anatomy. Through dissection and illustration, Leonardo was revolutionary in his studies of the human nervous and cardiovascular system. This work helped to correct the misconceptions that had been believed for quite some time because of that authority that Galen had. Click here to read more about the public health discoveries during this era in history.

Seeing what had never been seen before

The first microscope was invented in the 1590’s by a father-son team, Hans and Zacharias Janssen. This invention was the catalyst to the eventual discoveries of infectious agents, like bacteria and viruses.

Less than one hundred years after the Janssen’s compound microscope was invented, an individual named Antony van Leeuwenhoek began to make his own microscopes as sort of hobby. This pastime led van Leeuwenhoek to his discover many microscopic entities that are relevant to the human body and disease, such as bacteria, parasites, and various human cells.

Edward Jenner: The pioneer of vaccination

In the last part of the 1700’s Edward Jenner noticed that dairymaids who had contracted cowpox (a much less severe infection from the variola virus, the virus that causes smallpox) were immune to smallpox. Jenner tested this theory, and the results supported the hypothesis that exposure to a small, homogenous dose of an agent will allow the body become immune to subsequent exposures.

Thanks to the discovery of vaccination, smallpox is the only infectious disease in the history of disease that has been eradicated. Humans no longer have to be vaccinated for smallpox, because it has been completely destroyed.

Although there is no current threat of the resurgence of the variola virus into our ecosystem as a bioterrorist threat, the world is prepared if such a thing were to happen. Doses of smallpox reside at the CDC and the Russian State Centre for Research on Virology and Biotechnology in the event smallpox vaccines would need to be made again.

John Snow

Over 150 years before Game of Thrones dominated popular culture, a British physician by the name of John Snow became the father of modern epidemiology due to his investigation into a cholera outbreak in London years before the Germ Theory was posited. The leading theory about cholera was that it was transmitted airborne via miasma , but Snow refuted that theory. When a cholera outbreak occurred in a London neighborhood, Soho, Snow created a map of that area, plotting the cholera cases. Eventually, he was able to trace them to the Broad Street water pump. Once the pump handle was removed, cholera cases began to decrease. Today, it is known that cholera is a bacterial disease that is easily transmitted through eating food or drinking water that is contaminated with fecal matter. It is not transmitted through air droplets, thus supporting Snow’s findings and disproving the popular belief at that time. Figure 1.7 illustrates the cholera map. The red boxes indicate the cholera cases. The green pump in the middle signifies the Broad Street Pump. This article provides a synopsis of the cholera outbreak and Snow’s contribution to public health. He is often referred to as the original epidemiologist.

Early United States

Early United States

During the first one hundred years of settlement in the United States, there was not a formal public health system. The role of a health officer was often a part-time role, and the focus was not on serving the whole community. In fact, health leaders were usually among the social elite, further dividing the public based on class. There was a leading assumption that disease and poverty were positively associated. Cleanliness was next to godliness, so individuals who were seen as “dirty” (often because they lived in poverty and didn’t have the same access to goods and services as higher classes) were seen as morally corrupt. (Scutchfield, F.D., & Keck, C.W., 1997). Principles of public health practice. Albany, NY: Delmar Publishers, Inc. Chapter 2: History and Development of Public Health (Author: Fee, E.).

Although there was this leading thought linking cleanliness to godliness, the quick urbanization along the eastern seaboard without proper public health measures lead to increasingly unsanitary conditions. For example, it was not uncommon for garbage and decay to pile up two or three feet high in New York City. Mortality rates were high among the working class due to poor sanitary conditions. Over half of children from working class families died before the age of five.

Lemuel Shattuck

In typical historic fashion, there was an equal and opposite reaction to the dismal public health conditions of the early 1800’s, and reform groups started growing in some cities in the Eastern United States. One of the most notable people coming out of these groups is Lemuel Shattuck, who published Report of the Massachusetts Sanitary Commission in 1850. In this exhaustive report, he included a series of recommendations that dealt with hygiene, education, to help prevent, control, and manage the diseases affecting the population at the time. He sparked formalized school health education. This was the first time in US documented history that there was this call to have some sort of formalized health education.

Table 1 includes some of Shattuck’s recommendations with an example of how they are implemented today.

Table 1. Shattuck Report Recommendations and Current Applications

| Recommendation | How it exists today |

| Establishing state and local boards of health | Every state has a department of health, and every local jurisdiction (e.g. city or county) has a department of health. |

| Separating drinking water from sewage water | We now take this for granted, but we have separate plumbing systems for drinking water and our sewage waste water. This significantly decreased the number of diseases and deaths due to consuming contaminated water. |

| Hiring health inspectors | Health inspectors are often on staff at the local health department, and inspect a variety of businesses, such as restaurants, salons, tattoo/piercing parlors, etc. |

| Keeping of vital statistic records | Birth, death, marriage and divorce records are kept for each state. They are often analyzed to get a sense of trends/needs in a community. |

| Establishing systems for data exchange | One good example of this is the system for tracking notifiable diseases called Supernatural Theory National Electronic Disease Surveillance System (NEDSS) Base System (NBS) |

| Promoting health in children | An early call for health education in schools. Research has shown that the earlier children are taught about health, the healthier they are likely to be. |

| Studying tuberculosis (TB) in more detail | TB was a highly contagious disease at the time and a leading cause of death. This recommendation supported an ongoing scientific investigation to further understand this disease. Although TB still plagues individuals globally, numbers in the US are relatively low (thanks to testing and treatment). https://www.cdc.gov/tb/statistics/default.htm |

| Supervising the mentally ill | In the mid-1800’s people with mental illness were forgotten members of society. They were brushed to the side. This recommendation created awareness that the mentally ill needed some sort of care (note: this was not quality care, necessarily). Eventually hospitals for the mentally ill were developed. Today, even though stigma still exists, mental health is viewed in the public health community as a legitimate and vital part of overall health and wellbeing. |

| Studying immigrants’ problems | As the proverbial “melting pot” during this time, the United States was a nation of immigrants. This recommendation recognized the need for infectious disease tracking and management, dealing with language barriers, etc. Tackling immigrant farm workers’ needs is a current public health issue. |

| Controlling smoke nuisances | The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is a federal agency that works to maintain safe air, soil, and water. In more recent years, smoking bans have further controlled exposure to tobacco smoke in public places. |

| Controlling of food adulteration | Food adulteration is also known as “food fraud” and means an ingredient has been intentionally replaced with something else. In the US, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is the federal agency tasked with controlling food adulteration. |

| Preaching of health in the churches | This is another example of the call for formalized health education. Today, and in theory, health is taught in public schools across the United States. |

| Establishing training schools for nurses | Until this time, becoming a nurse involved more of an apprenticeship than a formalized professional program. Not long after Shattuck’s report, the first nurse training programs were established in the United States. Today, however, nursing programs are offered at numerous levels (associates, bachelors, graduate) throughout the United States. |

| Teaching of sanitary science in medical school | By this time, formalized training of medical doctors existed in the United States. But they did not have specific training in sanitation. Today, however, sanitation is a vital practice in medicine to protect the health of patients. It is called sterile technique. |

| Including preventative medicine in clinical practice | Health educators have been advocating for the focus in clinical practice to be on prevention. While there is still more work to be done, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was revolutionary when its policy that mandated services considered preventative (e.g., contraceptives, vaccination) to have no out-of-pocket cost to the patient. |

Over the remaining decades of the nineteenth century, there were some slow public health developments, including the formation of the American Public Health Association (APHA) and The Marine Hospital Service, development of local and state boards of health, and further understanding the link between bacteria (in polluted water, for example) and disease (e.g. typhoid fever) during the ascend of bacteriology. (Scutchfield, F.D., & Keck, C.W., 1997). Principles of public health practice. Albany, NY: Delmar Publishers, Inc. Chapter 2: History and Development of Public Health (Author: Fee, E.).

Influenza of 1918

The influenza outbreak of 1918-1919 was the deadliest pandemic of the 1900’s. The infectious agent responsible was an H1N1 virus that stemmed from an avian (i.e. bird-related) origin. It is estimated that this flu infected about 500 million people and killed about 50 million people worldwide.

Antidotes like vaccines or antimicrobial medications did not exist, so the best measures to help prevent further spread were limited to quarantining, masking, practicing good hygiene, and limiting large gatherings. Of course, humans will be humans and did not consistently comply practice these measures.

Watch this video for more information on the flu of 1918:

Penicillin

Thanks to the work of Alexander Fleming, Howard Florey, Ernst Chain and their colleagues at Oxford University between the late 1920’s and 1940, the discovery that mold (or what was called “mold juice”) was capable to destroying harmful bacteria (specifically staphylococcus aureus) lead to the development and use of the first antibiotic, penicillin. This revolutionary discovery was responsible for treating and curing many life-threatening infectious diseases at the time. People starting living longer because they did not succumb to diseases like pneumonia and TB, two of the leading causes of death up until the discovery of penicillin, and were more likely to be susceptible to diseases that arise as we age.

Disease Causation Changes

Thanks to improved sanitary conditions and the discovery of penicillin, the leading causes of death in 1900 were no longer at the top of the list by the 1940’s. By the mid-1940’s the leading causes of disease look more like they do today, with heart disease, cancer, and unintentional injuries (i.e. “accidents”) at the top of the charts. As a result, more attention was on further study of these chronic diseases and unintended injuries.

The shift to studying chronic diseases in more detail led to many discoveries, including but not limited to the following:

- The discovery of treating diabetes with insulin

- The invention of more sophisticated imagining technology, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computerized axial tomography (CAT)

- Advancements in surgical technology (e.g. the use of lasers)

- Organ transplants

- Better understanding about the causes of disease

May Edward Chinn – A trailblazer in more ways than one

May Edward Chinn, a Massachusetts-born black woman became the first African American woman to graduate from what is now NYU School of Medicine. After receiving her degrees, she became a private practice physician in New York City. During her time as a practicing physician Dr. Chinn became impassioned to study cancer, leading to the development of several new cancer screening procedures, such as helping to develop and promote the pap smear (the test that can detect possible pre-cancerous cells of the cervix in women).

Jonas Salk

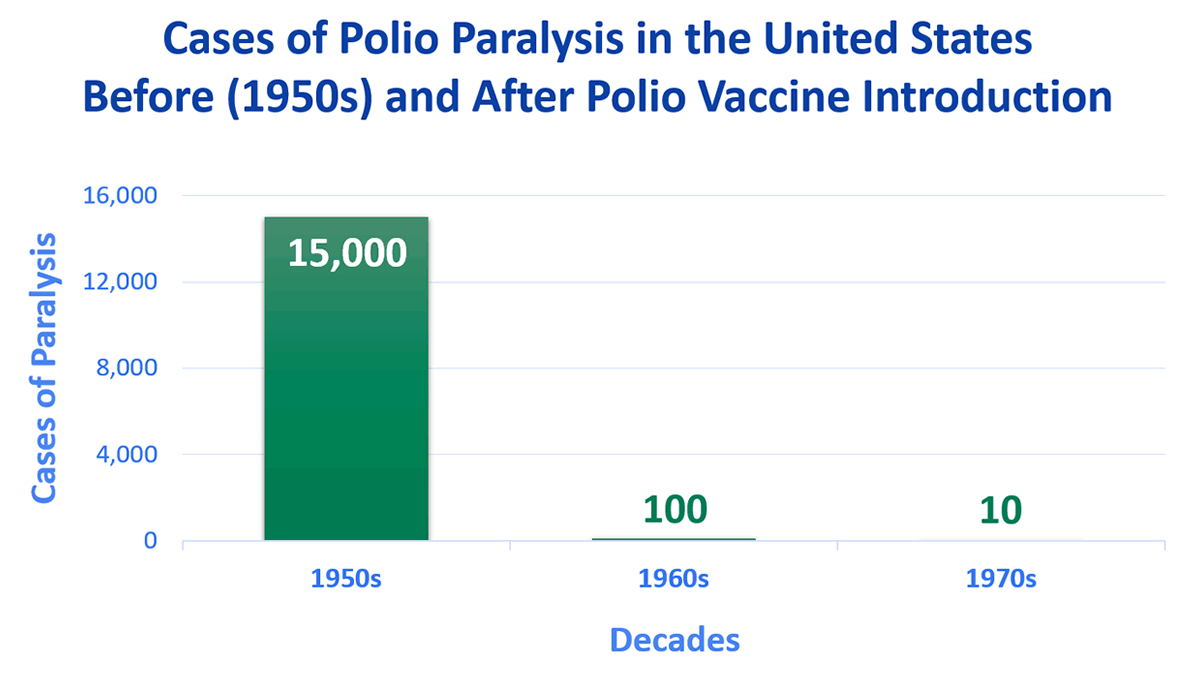

Despite the public health swift to exploring chronic disease, infectious diseases still persisted. Polio was a prominent viral infection in the mid-1900’s. It was a life-threatening disease that would cause a range of symptoms, including paralysis in severe cases. Hospitals were full of children and adults in iron lungs, a revolutionary respiratory device at the time. Polio was highly contagious; no one was exempt from being infected. One famous example being the 32nd president of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt, who contracted polio as a young man and was bound to a wheelchair during his presidency.

The number of polio cases declined drastically within a few years of the polio vaccination campaign, further supporting the effectiveness in immunizations in controlling the spread of viral infections.

Public Health: The long and winding history

The history of public health requires a separate textbook of its own, but it is necessary to at least include a synopsis of how public health was involved with – or excluded from – tackling infectious and chronic disease throughout history in the United States.

During the 1700’s and 1800’s the focus was on confronting infectious disease, because most illnesses and deaths were caused by infection linked to poor sanitation and person-to-person transmission. There were a few incidences, however, of public health reform during this time, including the formation of boards of health and the work of progressive social reform groups in advocating for social justice, abolishment of child labor, and improvements in maternal health. Although this work had mixed reactions, the economic advantages to keeping people healthy were becoming apparent when sanitary conditions improved and many infectious diseases became curable. One of the common threads throughout the history of public health was the ambiguity surrounding “who” is a public health professional. What training was needed? Throughout all of the significant eras of reform, trying times of war, and new disease discoveries, that question endured.

There were times, such as the era of Bacteriology, when a finite link existed between causative agent (i.e. a bacterium) and actual disease (e.g. tuberculosis). Controlling and managing public health endeavors were streamlined. So straightforward, in fact, that the role of public health professionals matched the role of the physician. This did not bode well for the respective professionals as physicians began to begrudge that such ambiguously trained public health professionals were being recognized for treating these infectious diseases. And this resentment has persisted. The contention between the medical model of treatment and the public health model of prevention still exists today.

After the fall of the bacteriology era, the role of public health professionals was once again multi-disciplinary. Even though the roles and responsibilities of public health professionals was still ill-defined, the aim of public health continued to be on reducing disease and improving overall health. There were many disciplines invested in these goals: sanitary engineers, economists, nurses, various scientists, and physicians. The latter dominated leadership positions in public health, as physicians were well-respected professionals and their words and actions held a lot of weight. Public health was synonymous with medicine for this reason.

Due to events such as World War II and the Great Depression, specialized training programs started to be offered at various colleges and universities. Concurrently, the federal government had established funding programs targeting specific diseases. Also, around this time the World Health Organization (WHO) coined its now classic definition of health. By the mid-1900’s, epidemiology was emerging as a vital public health discipline for tackling both infectious and chronic diseases measuring varying levels of health across a population. And the epidemiological triad became the new model of understanding the multiple causes of disease.

By the time of the polio vaccination campaign, public health was a well-established and defined profession. But certain political views permeating society condemned public health efforts as being “socialist” (e.g. the fluoridation of water to improve dental health in children), and public health efforts became fragmented.

Then, in the mid-1970’s our neighbors to the north published the Lalonde Report. This report served as a framework to guide Canadian health outcomes. The United States modeled this initiative in 1979 with the first Surgeon General’s report entitled, Healthy People: The Surgeon General’s Report on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. One year later, the first Healthy People framework was published with a set of goals and objectives to improve the health of Americans by 1990. This framework continues to be published every ten years.

Looking forward

Throughout the remainder of the 20th Century and the start of the 21st Century, new diseases and issues have been and will continue to be identified. Since 1980, the world has seen pandemics such as HIV, Ebola, Zika, Swine flu, Avian flu, and SARS (including COVID-19). Chronic and behavioral health issues such as the obesity and opioid epidemics have emerged. Future outbreaks and challenges will continue to emerge.

Diseases have been documented since the start of human record. Infectious diseases dominate the historical timeline of disease due to the lack of scientific understanding about things like basic human anatomy and physiology, sanitation, causes of disease, and treating various types of infections. It took the development of a powerful antidote to bacterial infections and the creation of vaccines for several of the most deadly viral infections for there to be a shift to chronic disease exploration. The next chapter dives deeper into comparing and contrasting the leading causes of death in recent history, looking specifically at this change from infectious disease to chronic disease.

Recall quiz

Recall quiz:

Discussion Questions

1). Describe when the disease focus shifted from infectious to chronic disease in the United States. About what decade did this happen? What important discoveries led to this shift?

2). Identify at least ten recommendations of the Shattuck Report.

3). The choice of whether or not to get vaccinated for COVID-19 has been a hot topic of discussion lately. This brings up the question: Where does the line between respecting personal freedom and protecting the greater good begin and end? When does it become a public health responsibility of an individual to adhere to vaccination guidelines?

Chapter Activity

- Visit a graveyard or cemetery, and look at the birth and death dates on the tombstones. Make connections to the various diseases discussed in the chapter. For example, someone who died young in the early/mid-1900’s may have suffered from polio. Important: Please be respectful!

references

Adams, D. P. (2021). Foundations of Infectious Disease: A Public Health Perspective. Jones & Bartlett.

American Chemical Society. (2015). Alexander Fleming discovery and development of Penicillin. https://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/flemingpenicillin.html

American Physical Society. (2004, March). Lens crafters circa 1590: Invention of the microscope. Www.aps.org. https://www.aps.org/publications/apsnews/200403/history.cfm

BBC. (2014a). Historic figures: Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564). https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/vesalius_andreas.shtml

BBC. (2014b). Historic figures: John Snow (1813 – 1858). https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/snow_john.shtml

Berish, A. (2016). FDR and polio. Fdrlibrary.org. https://www.fdrlibrary.org/polio

Berkshire Museum. (n.d.). Trailblazing cancer researcher: May Edward Chinn. Retrieved September 29, 2022, from https://explore.berkshiremuseum.org/digital-archive/legendary-locals/may-edward-chinn

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019a). Data & statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/tb/statistics/default.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019b). Polio. https://www.cdc.gov/polio/what-is-polio/polio-us.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019c). Smallpox: Bioterrorism: The threat. https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/bioterrorism/public/threat.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019d, March 20). 1918 Pandemic (H1N1 virus). https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-pandemic-h1n1.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, February 20). History of smallpox. https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/history/history.html

Cleveland Clinic. (2021, June 17). Bubonic Plague (Black Death): What is it, symptoms, treatment. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/21590-bubonic-plague

Hamann, B. (2007). Disease: Identification, Prevention, and Control (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

Hodges, B. C., & Videto, D. M. (2011). Assessment and Planning in Health Programs. Jones & Bartlett.

Institute of Medicine (US). (2011). A History of the Public Health System. Nih.gov; National Academies Press (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK218224/

National Museum of American History. (2021, September 27). Whatever happened to polio? https://americanhistory.si.edu/polio

Seabert, D., & Mckenzie, J. F. (2022). An Introduction to Community & Public Health. Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Shattuck, L. (1850). Report of the Sanitary Commission of Massachusetts: 1850. Dutton & Wentworth. http://aspphwebassets.s3.amazonaws.com/delta-omega/archives/shattuck.pdf

Shiel, W. (2021, June 3). Medical Definition of Hippocratic Oath. MedicineNet. https://www.medicinenet.com/hippocratic_oath/definition.htm

Sooke, A. (2014). Leonardo da Vinci’s groundbreaking anatomical sketches. https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20130828-leonardo-da-vinci-the-anatomist

Tulchinsky T. H. (2018). John Snow, Cholera, the Broad Street Pump; Waterborne Diseases Then and Now. Case Studies in Public Health, 77–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-804571-8.00017-2

Tuthill, K. & Van Wyk, R. (2003). John Snow and the Broadstreet pump: On the trail of an epidemic. Cricket, 31(3), pp. 23-31.

U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2018). Preventive health services. HealthCare.gov. https://www.healthcare.gov/coverage/preventive-care-benefits/

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2021, August 24). History of Healthy People. Health.gov. https://health.gov/our-work/national-health-initiatives/healthy-people/about-healthy-people/history-healthy-people

University of Pennsylvania Nursing. (2019). Nursing through time. Upenn.edu. https://www.nursing.upenn.edu/nhhc/nursing-through-time/

The belief that higher powers are in sole control over disease occurrence and death.

Artificial canals that carry water.

Number of deaths in a defined population over a specified period of time.

The infectious agent no longer naturally exists in our environment.

Remember Galen in ancient Rome? Not much has changed over time.

"Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity."https://www.who.int/about/governance/constitution

A pandemic is when an outbreak of a disease has confirmed cases across multiple continents.

Sudden acute respiratory syndrome

An epidemic is when a disease has multiple confirmed cases in a particular community in a given period of time.