June 21, 1851

May I say a few words? I want to say a few words about this matter.

I am a woman’s rights [sic].

I have as much muscle as any man, and can do as much work as any man.

I have plowed and reaped and husked and chopped and mowed, and can any man do more than that?

I have heard much about the sexes being equal; I can carry as much as any man, and can eat as much too, if I can get it.

I am as strong as any man that is now.

As for intellect, all I can say is, if women have a pint and man a quart – why can’t she have her little pint full?

You need not be afraid to give us our rights for fear we will take too much, for we cant take more than our pint’ll hold.

The poor men seem to be all in confusion, and don’t know what to do.

Why children, if you have woman’s rights, give it to her and you will feel better.

You will have your own rights, and they wont be so much trouble.

I cant read, but I can hear.

I have heard the bible and have learned that Eve caused man to sin.

Well if woman upset the world, do give her a chance to set it right side up again.

The Lady has spoken about Jesus, how he never spurned woman from him, and she was right.

When Lazarus died, Mary and Martha came to him with faith and love and besought him to raise their brother.

And Jesus wept – and Lazarus came forth.

And how came Jesus into the world?

Through God who created him and woman who bore him.

Man, where is your part?

But the women are coming up blessed be God and a few of the men are coming up with them.

But man is in a tight place, the poor slave is on him, woman is coming on him, and he is surely between-a hawk and a buzzard.

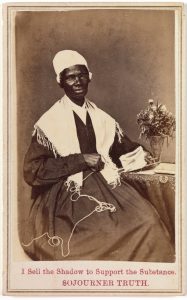

“AIN’T I A WOMAN?” SPEECH (TRANSCRIBED BY FRANCES DANA GAGE)

April 23, 1863

Well, chillen, whar dar’s so much racket dar must be som’ting out o’kilter.

I tink dat, ’twixt de niggers of de South and de women at de Norf, all a-talking ’bout rights, de white men will be in a fix pretty soon.

But what’s all this here talking ’bout?

Dat man ober dar say dat women needs to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have de best place eberywhar.

Nobody eber helps me into carriages or ober mud-puddles, or gives me any best place.

-And ar’n’t I a woman?

Look at me.

Look at my arm.

I have plowed and planted and gathered into barns, and no man could head me.

-and ar’n’t I a woman?

I could work as much as (c) eat as much as a man, (when (d) I could get it,) and bear de lash as well

-and ar’n’t I a woman?

I have borne thirteen chillen, and seen ’em mos’ all sold off into slavery, and when I cried out with a mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard

-and ar’n’t I a woman?

Den dey talks ’bout dis ting in de head.

What dis dey call it?

Dat’s it, honey.

What’s dat got to do with women’s rights or niggers’ rights?

If my cup won’t hold but a pint and yourn holds a quart, wouldn’t ye be mean not to let me have a little half-measure full?

Den dat little man in black dar, he say women can’t have as much rights as man ’cause Christ wa’n’t a woman.

Whar did your Christ come from?

Whar did your Christ come from?

From God and a woman.

Man had nothing to do with him.

If de fust woman God ever made was strong enough to turn de world upside down all her one lone, all dese togeder ought to be able to turn it back and git it right side up again, and now dey is asking to, de men better let ’em.

Bleeged to ye for hearin’ on me, and now ole Sojourner ha’n’t got nothin’ more to say.

Discussion Questions

- How do you think the mention of Mary and Jesus is significant to Truth’s argument?

- How does Truth unveil the hypocrisy of white men and their treatment of women?

- Does Truth’s comparison of herself to a man, especially the “bear the lash” remark strengthen or weaken her argument? Why or why not?

- What does Truth compare “intellect” to and how is it relevant to her argument?

- Explain why or why not you agree with Truth when she says, “If the first woman God ever made was strong enough to turn the world upside down all alone, these women together ought to be able to turn it back, and get it right side up again! And now they is asking to do it, the men better let them.”

- Compare Gage’s and Robinson’s translations. Which translation seems to be a more accurate version of Truth’s speech? Why?