Written Language

One of the reasons I insist on being called a speech-language pathologist (SLP) is that not everything we do in our profession involves speech. As experts in language, we have a role in working with children on understanding and producing written language. It is clear to most people that reading and writing skills are critical for academic success. Increasingly, these skills are becoming important for social success. Much social communication now occurs in written form, including emails, texts, and social media posts.

Theoretical Perspectives

Speech-language pathologists need to understand the relations among spoken and written language in order to be able to comprehensively evaluate a child’s entire language system. As noted in the introduction to this book, spoken and written language may not constitute separate constructs (Nelson et al., 2022). However, often other professionals may not recognize the SLP’s role in working with reading and writing, and many SLPs themselves do not feel competent to address written language (Serry, 2013). Outlined here are theoretical models describing the relations between oral and written language.

The Simple View of Reading

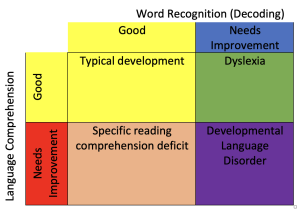

The simple view of reading posits that two processes contribute to reading: decoding and language comprehension (Gough & Tumner, 1986). Decoding involves the ability to read accurately; that is, to correctly map the graphemes to their speech sounds and combine the sounds to form words. Decoding involves phonological ability. Children with dyslexia have deficits in decoding, but intact language comprehension. These children understand written language when they are able to decode it, but inaccurate decoding can result in inaccurate comprehension. The most widely held theory of developmental dyslexia is the phonological representations hypothesis, whereby individuals with dyslexia do not process phonological representations that are as specific as the phonological representations processed by typical readers (Melby-Lervag, et al., 2012). Phonological deficits are posited to underlie dyslexia.

Children with developmental language disorder (DLD) typically have deficits in both phonological and non-phonological language skills (Bishop & Snowling, 2004; Catts, et al., 2006). Deficits in phonology underlie dyslexia; in contrast, some children with DLD do not have deficits in phonology (Catts et al.,2005). Children with dyslexia perform similarly to typically developing peers on language measures, with the exception of phonology, whereas children with DLD perform below typically developing peers on language measures. Children with DLD also perform below children with dyslexia on measures of vocabulary and nonword repetition. Children with dyslexia display more deficits on rapid automatic naming than children with DLD. Children with dyslexia and children with DLD show similar deficits in literacy (Oliveira et al., 2021). Although dyslexia and DLD are separate disorders, they occur comorbidly in some children (Catts et al., 2005).

Another group of children with reading disorders is poor reading comprehenders. Poor reading comprehenders decode accurately, suggesting intact phonological systems, but have deficits in other areas of language, resulting in poor understanding of text (Bishop & Snowling, 2004; Catts et al., 2006).

Given that oral expression, listening comprehension, word recognition, and reading comprehension are correlated, it is important that SLPs comprehensively assess both oral and written language, and provide intervention as needed (Ebert & Scott, 2016).

The Triangle Model

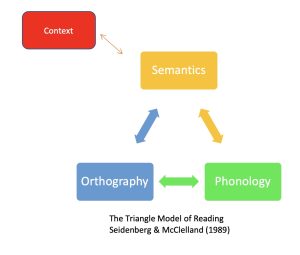

The Triangle Model of visual word recognition highlights the bidirectional relations among semantics, phonology, and orthography (Seidenberg & McClellend (1989).

Dual Route Cascaded Model of Visual Word Recognition

The dual route cascaded model of visual word recognition (Coltheart et al., 2001) suggests that words in print get translated into visual feature units, then letter units. From the letter units, the representation goes either through the grapheme-phoneme rule system (lexical pathway) or to the orthographic input lexicon and then the phonological output lexicon (phonological pathway). Both the orthographic input lexicon and the phonological output lexicon have bi-directional relations with the semantic system. From the grapheme-phoneme rule system or the phonological output lexicon, the representation goes through the phoneme system and then to speech. Typical readers use the lexical pathway for high-frequency words, and the phonological pathway for low-frequency words. Individuals with dyslexia have been shown to rely on the lexical pathway, even for unfamiliar words. This can lead to slower reading or substituting a higher-frequency word for a lower frequency word.

Cognitive Foundations Framework

Cognitive foundations framework

Tunmer and Hoover (2019) describe the cognitive foundations framework, which describes the underlying abilities for learning to read. They define reading comprehension as the “ability to extract and construct linguistically-based meaning, both literal and inferred, from written text (p.77).

Ehri’s Phase Theory of Word Recognition

Ehri (1987; 2020) suggests four phases of development of word reading. The first phase is the pre-alphabetic phase, in which use visual cues, but not letter-sound relationships to read and write words. For example, a child could recognize an exit sign and say, “exit,” but they are recognizing the visual wordform, rather than using knowledge of letters and sounds. In the partial-alphabetic phase, readers begin to use knowledge of letters and sounds. Readers in this phase often rely on the first letter and context to read or spell a word. They may also use the last letter, and perhaps some of the other letters. In the alphabetic phase, readers use each letter in a word to decode and spell. In the consolidated alphabetic phase, readers are aware of spelling patterns and can apply this knowledge to decode and spell words.

The SLP’s Role in Working With Children with Written Language Disorders

The theoretical perspectives described above highlight the relations between oral and written language, suggesting that SLPs have an important role in working with children with written language disorders. The American Speech-Language Hearing Association (ASHA) includes working with individuals with written language disorders in the scope of practice of SLPs (2016). Given the extensive knowledge of language that we have as SLPs, it is important that we are involved in the prevention, assessment, and intervention of children with disorders in reading and writing. This involves educating others about our role with these children. When working with children with written language disorders, we must collaborate with other professionals, including regular and special education teachers, school psychologists, and reading specialists. The Common Core State Standards (CCSS; 2010, National Governors’ Association) highlight the importance of interprofessional collaboration in language, reading, and writing. When working with interprofessional colleagues, it is important to avoid duplication of services; instead, roles and responsibilities of each team member should be defined and mutually accepted. Collaboration to use consistent language and strategies for working with each individual is essential in order to ensure generalization of strategies and skills.

In the introduction to the intervention section of this text, Response to Intervention (RtI) and Multi-Tiered Systems of Support were described. Many of the reading and writing interventions described in this chapter on reading and writing can be provided in multiple tiers of RtI. Collaboration with interprofessional colleagues is critical to facilitating improved reading and writing for students exhibiting academic difficulty. Based on the extensive education in language development and disorders, SLPs play a key role in this aspect of academic success.

Written Language in Children with DLD

A “Matthew effect” has been noted for reading deficits, whereby “the rich get richer and the poor get poorer” (Stanovich, 1986). Children who enter kindergarten with good reading ability continue to make progress, whereas children who enter school with poor reading ability make slower gains, thereby falling further and further behind. Children who have difficulty learning to read typically have those deficits persist throughout their lives unless intervention is provided. As language experts, it is critical that speech-language pathologists collaborate with other school personnel to identify and remediate reading and writing deficits.

Two types of orthographic knowledge underlie spelling: general and specific. General orthographic knowledge refers to understanding acceptable letter patterns in a written language, whereas specific, or lexical, orthographic knowledge refers to mental representations of how particular words are spelled (Conrad et al., 2013). Children with DLD use general orthographic knowledge more accurately than specific orthographic knowledge. They can perform similarly to peers in both speed and accuracy when using general orthographic knowledge, but perform more similarly to younger children when needing to use specific orthographic knowledge (Williams et al., 2021).

Children with DLD earn lower scores on writing on measures of both macrostructure and microstructure (Graham et al., 2020). Macrostructure refers to discourse-level analyses. The 6+1 Trait Model of Instruction and Assessment is one model of assessing macrostructure. It is comprised of the following constructs that characterize high quality writing: ideas, organization, voice, word choice, sentence fluency, conventions, and presentation. Ideas are the content, which includes the main idea and supporting details. Organization refers to the structure of the writing, including logical sequencing and connecting ideas. Voice is reflected by writers conveying their own personalities through their writing, making the piece sound unique to them. Word choice considers the precise, rich use of words. Word choice does not necessarily reflect the use of exceptionally vocabulary; rather, it reflect the ability to use common words well. Sentence fluency is comprised of the use of a variety of sentence types that have a good rhythm when read aloud. Spelling, punctuation, grammar/usage, and paragraphing comprise conventions. Presentation includes visual elements of the text, such as a balance of white space with graphics and text, neatness, handwriting or font selection, and general appearanceThe 6+1 traits model is one measure of writing quality. Genre-specific measures of macrostructure for narrative, expository, and persuasive writing, such as the Narrative Scoring Scheme (Miller et al., 2016), ExMac (Karasinski, 2022), and Persuasive Scoring Scheme (Miller et al., 2016), represent a separate dimension from the 6+1 traits score (Karasinski, 2022).

Microstructure refers to word- and sentence-level analyses. Microstructure measures comprise the dimensions of accuracy, productivity, and complexity (Hall-Mills & Apel, 2015; Karasinski, 2022; Kim et al., 2014; Puranik, et al., 2008; Wagner et al., 2011). Accuracy includes spelling, punctuation, and capitalization. Productivity is comprised of number of different words (NDW), total number of words (NTW), number of ideas, number of clauses, and number of T-units (main clause + dependent clause(s)). Complexity includes mean length of utterance (MLU) and clausal density.

Children with DLD have particular difficulty with silent letters when spelling (Godin et al., 2022). Their spelling is similar to that of younger, vocabulary-matched peers (Dockrell & Connelly, 2015).

Deficits in both oral and written language can persist into adulthood in individuals with DLD. Botting (2020) revealed that, although 25% of young adults with DLD scored within the typical range on a standardized measure of reading, 58% scored between one and two standard deviations below the mean, and 17% fell more than two standard deviations below the mean. Thus, it is crucial that the written language of individuals with DLD is explicitly addressed.

References

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2016). Scope of practice in speech-language pathology [Scope of practice]. Available from www.asha.org/policy/

Bishop, D. V. M., & Snowling, M. J. (2004). Developmental dyslexia and specific language impairment: Same or different? Psychological Bulletin, 130(6).

Botting, N. (2020). Language, literacy and cognitive skills of young adults with developmental language disorder (DLD). International journal of language & communication disorders, 55(2), 255-265.

Catts, H. W., Adlof, S. M., Hogan, T. P., & Weismer, S. E. (2005). Are specific language impairment and dyslexia distinct disorders? Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 48(6), 1378–1396. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092- 4388(2005/096)

Catts, H. W., Adlof, S. M., & Weismer, S. E. (2006). Language deficits in poor comprehenders: A case for the simple view of reading. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 49, 278-293.

Catts, H. W., Adlof, S. M., Hogan, T. P., & Weismer, S. E. (2005). Are specific language impairment and dyslexia distinct disorders?.

Coltheart, M., Rastle, K., Perry, C., Langdon, R., & Ziegler, J. (2001). DRC: a dual route cascaded model of visual word recognition and reading aloud. Psychological Review, 108(1), 204.

Conrad, N. J., Harris, N., & Williams, J. (2013). Individual differences in children’s literacy 651 development: The contribution of orthographic knowledge. Reading and Writing, 26(8), 652 1223-1239, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-012-9415-2

Dockrell, J., & Connelly, V. (2015). The role of oral language in underpinning the text generation difficulties in children with specific language impairment. Journal of Research in Reading, 38, 18-34.

Ebert, K., & Scott, C. (2016). Bringing the Simple View of Reading to the clinic: Relationships between oral and written language skills in a clinical sample. Journal of Communication Disorders, 62, 147-160.

Ehri, L.C. (1987). Learning to read and spell words. Journal of Reading Behavior, 19(1), 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/10862968709547585

Ehri, L. C. (2020). The science of learning to read words: A case for systematic phonics instruction. Reading Research Quarterly, 55, S45-S60.

Galuschka, K., Gorgen, R., Kalmar, J., Haberstroh, S., Schmalz, X., & Schulte-Korne, G. (2018). Effectiveness of spelling interventions for learners with dyslexia: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Educational Psychologist, 55(1), 1-20.

Godin, M., Berthiaume, R., & Daigle, D. (2021). The “sound of silence”: Sensitivity to silent letters in children w ith and without developmental language disorder. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 52, 1007-1019.

Gough PB, Tunmer WE (1986): Decoding, reading, and reading disability. Remedial and Special Education 7, 6 –10.

Graesser, A. C., McNamara, D. S., & Kulikowich, J. M. (2011). Coh-Metrix: Providing multilevel analyses of text characteristics. Educational Researcher, 40(5), 223–234.

Hall-Mills, S., & Apel, K. (2015). Linguistic feature development across grades and genre in elementary writing. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 46(3), 242-255.

Hoover, W. A., & Gough, P. B. (1990). The simple view of reading. Reading and writing, 2, 127-160.

Kim, Y., Otaiba, S., Folsom, J., Greulich, L., & Puranik, C. (2014). Evaluating the dimensionality of first-grade written composition. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 57, 199–211. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2013/12-0152)

Koutsoftas, A., & Gray, S. (2012). Comparison of narrative and expository writing in students with and without language-learning disabilities. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 43, 395-409.

Levesque, K. C., Breadmore, H. L., & Deacon, S. H. (2021). How morphology impacts reading and spelling: Advancing the role of morphology in models of literacy development. Journal of Research in Reading, 44(1), 10-26.

McMaster, K. L., Kunkel, A., Shin, J., Jung, P., & Lembke, E. (2018). Early Writing Intervention: A Best Evidence Synthesis. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 51(4), 363-380.

Melby-Lervåg, M., Lyster, S.-A. H., & Hulme, C. (2012). Phonological skills and their role in learning to read: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 138(2), 322–352. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026744

Miller, J., & Iglesias, A. (2016). Systematic analysis of language transcripts (SALT): Research Version 16 [Computer Software]. Middleton, WI: SALT Software, LLC.

National Early Literacy Panel. (2008). Developing early literacy: Report of the National Early Literacy Panel. National Center for Family Literacy.

Nelson, N. (2018). How to code written language samples for SALT analysis. Perspectives of Language Learning and Education, 3, 45–55.

Nelson, N. W., Plante, E., Anderson, M., & Applegate, E. B. (2022). The dimensionality of language and literacy in the school-age years. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 65(7), 2629-2647.

Oliveira, C. M., Vale, A. P., & Thomson, J. M. (2021). The relationship between developmental language disorder and dyslexia in European Portuguese school-aged children. Journal of Clinical & Experimental Neuropsychology, 43 (1), 46-65. https://doi-org.ezproxy.gvsu.edu/10.1080/13803395.2020.1870101

Petersen, D. B., Mesquita, M. W., Spencer, T. D., & Waldron, J. (2020). Examining the Effects of Multitiered Oral Narrative Language Instruction on Reading Comprehension and Writing: A Feasibility Study. Topics in Language Disorders, 40(4), E25-E39.

Price, J. & Jackson, S. (2015). Procedures for obtaining and analyzing writing samples of school-age children and adolescents. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 46, 277-293.

Puranik, C., Lombardino, L., & Altmann, L. (2008). Assessing the microstructure of written language using a retelling paradigm. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 17, 107–120. https://doi.org/10.1044/1058-0360(2008/012)

Seidenberg, M. S., & McClelland, J. L. (1989). A distributed, developmental model of word recognition and naming. Psychological Review, 96(4), 523–568. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.96.4.523

Serry, T. (2013). Capacity to support low-progress readers at school: Experiences of speech-language pathologists. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 15, 623–633. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2012.754944

Spencer, T. D., & Petersen, D. B. (2018). Bridging oral and written language: An oral narrative language intervention study with writing outcomes. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 49(3), 569-581.

Spencer, T. D., & Petersen, D. B. (2016). Story Champs 2.0: A multi-tiered language intervention program. Laramie, WY: Language Dynamics Group. Retrieved from http://www. languagedynamicsgroup.com

Stanovich, K. E. (1986). Cognitive processes and the reading problems of learning disabled children: Evaluating the assumption of specificity. In J.Torgesen & B.Wong (Eds.), Psychological and educational perspectives on learning disabilities (pp. 87–131). NewYork:Academic Press

Tunmer, W.E., & Hoover, W.A. (2019) The cognitive foundations of learning to read: a framework for preventing and remediating reading difficulties, Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties, 24(1), 75-93, DOI: 10.1080/19404158.2019.1614081

Wagner, R., Puranik, C., Foorman, B., Foster, E., Wilson, L., Tschinkel, E., & Kantor, P. (2011). Modeling the development of written language. Reading and Writing, 24, 203–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-010-9266-7

Williams, G. J., Larkin, R. F., Rose, N. V., Whitaker, E., Roeser, J., & Wood, C. (2021). Orthographic knowledge and clue word facilitated spelling in children with developmental language disorder. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 64(10), 3909-3927.

the ability to map the graphemes to their speech sounds and combine the sounds to form words

neurobiological term for a phonological disorder that results in poor decoding of written language

Readers who decode accurately but do not understand what they have read. These children have deficits in broader language, but not in phonology.

The spelling system of a language