Intervention

Purpose of Intervention

Traditionally, we think of the purpose of intervention as fixing the underlying problem. However, this is not always possible. Olswang and Bain (1991) provided two additional purposes for intervention. One is changing the disorder. When we endeavor to change the disorder, we focus on improving aspects of the child’s language by teaching specific behaviors. Another purpose of intervention can be to teach strategies to compensate for deficits in language. A fourth purpose could be to change the context in which the child communicates, such as by educating others in the child’s environment how best to communicate with the child (Paul, Norbury, & Gosse, 2018). An intervention plan may include multiple purposes, depending on the needs of the child.

Owens’s (2014) functional language approach highlights the social aspect of language. This model reflects the idea that language is a dynamic process, rather than a product. Intervention needs to be focused on overall communication, targeting language as a vehicle for communication, rather than focusing solely on language itself. Rather than viewing a child’s language deficits as solely existing within the child, intervention must be family-centered and environmentally-based. Generalization, or the ability to apply what is achieved in therapy to new exemplars or contexts, needs to be considered at the beginning of treatment planning, rather than at the end of treatment once goals have been achieved in structured contexts. It is often appropriate for language intervention to occur in the natural setting, such as the classroom, rather than as “pull-out” therapy in the SLP’s office. This ensures that the child is learning and practicing new skills in the environment in which they will be used.

Alignment with Educational Standards

SLPs working in schools typically need to show academic and/or social-emotional impact of the language disorder in order to work with a child in that setting. Thus, knowledge of the academic standards is critical for understanding the expectations placed on school-aged children. Goals should align with educational standards, or should target foundational skills necessary for meeting the standards. SLPs working with school-aged children need to be familiar with the educational standards in the states in which they practice.

Common Core State Standards

The Common Core State Standards (CCSS) provide standards for kindergarten through twelfth grade students for math and English language arts (ELA). These standards have been adopted by most states. This state-led initiative aimed to improve college and career readiness for students in the United States, and to have consistency around what students should be able to do at each grade level and definitions of proficiency across states. States that have not adopted the CCSS will have their own standards for math and ELA. SLPs working in those states should familiarize themselves with the state educational standards.

CCSS Math Standards

The CCSS Math Standards contain the following eight standards for mathematical practice, which are ways students should engage with the content:

- Make sense of problems and persevere in solving them

- Reason abstractly and quantitatively

- Construct viable arguments and critique the reasoning of others

- Model with mathematics

- Use appropriate tools strategically

- Attend to precision

- Look for and make use of structure

- Look for and express regularity in repeated reasoning

(National Governors Association Center for Best Practices, Council of Chief State School Officers, 2010b, p. 6-8)

The CCSS for Mathematics also contain grade-specific standards for mathematical content, which include both procedure and understanding. Although math may not traditionally be considered an area of focus for SLPs, language underlies the ability to meet many of the math standards. In the first three standards for mathematical practice, there are terms and phrases that clearly suggest involvement of language, such as make sense of, reason, and construct arguments and critique reasoning. When there are concerns raised about a child’s performance in math, the SLP should obtain information from the teacher regarding the child’s understanding of the language involved in math. If the child is exhibiting difficulty with the language of math, the SLP should complete a language screening to determine whether an evaluation of the child’s language should be conducted.

CCSS ELA Standards

The CCSS ELA standards include standards for reading, writing, speaking, listening, and language and highlight an interdisciplinary approach to ELA. Standards are included for narrative, informational, and argument/opinion discourse types in spoken and written modalities. In addition to grade-specific standards, the CCSS for ELA include the following anchor standards.

Key Ideas and Details

- Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text.

- Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development; summarize the key supporting details and ideas.

- Analyze how and why individuals, events, and ideas develop and interact over the course of a text.

Craft and Structure

- Interpret words and phrases as they are used in a text, including determining technical, connotative, and figurative meanings, and analyze how specific word choices shape meaning or tone.

- Analyze the structure of texts, including how specific sentences, paragraphs, and larger portions of the text (e.g., a section, chapter, scene, or stanza) relate to each other and the whole.

- Assess how point of view or purpose shapes the content and style of a text. figurative meanings, and analyze how specific word choices shape meaning or tone.

Integration of Knowledge and Ideas

- Integrate and evaluate content presented in diverse media and formats, including visually and quantitatively, as well as in words.*

- Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, including the validity of the reasoning as well as the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence.

- Analyze how two or more texts address similar themes or topics in order to build knowledge or to compare the approaches the authors take.

Range of Reading and Level of Text Complexity

- Read and comprehend complex literary and informational texts independently and proficiently.

(National Governors Association Center for Best Practices, Council of Chief State School Officers, 2010b, p. 10).

It is clear that language ability underlies mastery of the ELA standards, and SLPs need to be involved in helping students attain this mastery.

Next Generation Science Standards

In addition to the need for consistent standards across the country for math and ELA, a need was recognized in the United States for consistency around science standards. The Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) were developed to meet this aim. These standards include three dimensions: Cross-Cutting Concepts, Science and Engineering Practices, and Disciplinary Core Ideas.

Cross-Cutting Concepts refers to broad constructs that facilitate students’ ability to make connections across the four science domains: life science, physical science, earth science, and engineering design. The Cross Cutting Concepts include the following:

- Patterns

- Cause and effect

- Scale, proportion, and quantity

- Systems and system models

- Energy and matter

- Structure and function

- Stability and change

Science and Engineering Practices encompass how scientists explore the natural world and how engineers design and build systems. These practices include

- Asking questions and defining problems

- Developing and using models

- Planning and conducting investigations

- Analyzing and interpreting data

- Using math and computational thinking

- Constructing explanations and designing solutions

- Arguing using evidence

- Obtaining, evaluating, and communicating information

Disciplinary Core Ideas are concepts that are important for multiple science or engineering disciplines. Life science core ideas are

- From molecules to organisms: Structures and processes

- Ecosystems: interactions, energy, and dynamics

- Heredity: Inheritance and variation of traits

- Biological evolution: Unity and diversity

For physical science, core ideas include

- Matter and its interactions

- Motion and stability: Forces and interactions

- Energy

- Waves and their application to technology for transferring information

Earth and space science core ideas are

- Earth’s place in the universe

- Earth’s systems

- Earth and human activity

The core ideas for engineering, technology, and applications of science are

- Engineering design

- Links among engineering, technology, science, and society

(National Research Council, 2012, p. 3).

Similarly to math, science might not be traditionally considered under the SLP’s purview, yet looking at the standards it is clear that a great deal of language is involved in science. As noted by Karasinski (2016), language is clearly involved in all of the eight Science and Engineering Practices, and language is foundational for at least the first three Cross-Cutting Concepts: patterns, cause and effect, and scale, proportion, and quantity. Language is also important for being able to understand and explain the additional four Cross-Cutting Concepts. Thus, if students are exhibiting difficulty with the science curriculum, the SLP should glean from the teacher whether language ability is impeding progress in learning science, and if it is, the SLP should screen the child’s language to determine if an evaluation is warranted.

Disciplinary Literacy

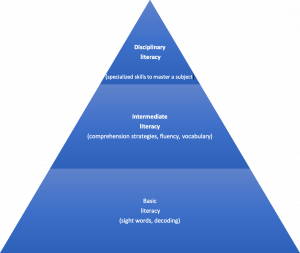

Reading the above standards for math, ELA, and science, the essential role language plays in the mastery of academic subjects is clear. The construct of disciplinary literacy, or the knowledge and practices that experts in a discipline use to create, communicate, and apply the knowledge of the discipline (Shanahan & Shanahan, 2008), further highlights the role of language in academics. In this framework, literacy begins with basic literacy, which includes decoding skills. Intermediate literacy follows with skills that apply to multiple tasks, such as comprehension strategies, fluency (reading rapidly, accurately, and with intonation), and understanding the meaning of high-frequency words.

Different academic subjects rely on different linguistic skills for mastery. For example, scientific terms contain Latin and Greek roots. Understanding these roots can help to understand the meanings of these words. However, this strategy would not be useful for understanding history vocabulary (Shanahan & Shanahan, 2012). In both math and science, students must be aware of nominalization, which refers to using a word that may be familiar to the student as a verb as a noun, giving it a different meaning (Fang et al., 2005, Shanahan & Shanahan, 2008 ). In contrast, history and literature do not have a great deal of nominalization (Shanahan & Shanahan, 2008). Math and science texts often include more concepts per sentence than other texts by using complex syntax to state intricate ideas in few words (Fang, 2005; Haarlar et al.).

A number of language skills have been found to contribute to performance in academic disciplines. For example, naming speed (Koponen et al., 2012), listening comprehension, (Aunola et al., 2004; Cowan et al., 2005), and phonological awareness (Kleemans et al., 2012) have been found to predict math ability. Comprehension of non-fiction, narratives, and complex syntax predict performance in science (Karasinski, 2016). The above examples highlight the need for SLPs to become involved if a student is exhibiting academic difficulty, even in subjects that might not be considered “language” initially. Ensuring that students are able to meet the language demands of the academic curriculum is an essential aspect to the SLP’s role in the school.

Response to Intervention and Multi-Tiered System of Support

Response to Intervention (RtI) is a type of Multi-Tiered System of Support (MTSS) whereby services are provided to children exhibiting difficulty in school at increasing levels. Core aspects of these systems include universal screenings, high-quality instruction, individualized interventions based on students’ needs, frequent progress monitoring, and decision-making based on student data. Typically, three tiers of support are described. Tier 1 interventions reflect evidence-based best practices for all students. The SLP’s role in Tier 1 is collaborating with teachers to provide insight into best practices for language development. SLPs may deliver whole-class lessons centered around language and literacy skills. Children who are not meeting benchmarks with Tier 1 instruction are referred for Tier 2 support, which consists of targeted instruction , often in small groups. This may be delivered by an SLP or a teacher, but often is delivered by a paraprofessional with guidance from the SLP or teacher. Tier 3 support is given to students who do not make the expected progress with Tier 2 intervention. This includes targeted, individualized interventions at a higher dosage than Tier 2 interventions, typically in smaller groups or as individual instruction. Tier 3 support can, but does not always, include the development of an Individualized Education Program (IEP). The interventions described in this chapter can be provided in multiple tiers of RtI.

One example of an evidence-based language intervention that has effectively been used in an MTSS framework is Story Champs (Spencer & Petersen, 2012). Story Champs targets a variety of language skills in the context of narrative and expository discourse. A randomized control trial revealed that when Story Champs was used as a whole-class intervention (Tier 1) by teachers for 15-20 minutes daily for four weeks, the students in the Story Champs classrooms scored higher at posttest than the children in the control classrooms on each of the outcome measures: narrative retell, personal story generation, expository retell, and narrative writing. Following the whole-class instruction, a random sample of students who did not make adequate progress were given Tier 2 intervention with Story Champs twice weekly for twenty minutes. The students who received the Tier 2 instruction scored higher on narrative and expository retells and personal stories than the at-risk peers who did not receive the Tier 2 instruction. The students receiving Tier 2 instruction performed better than average-performing or high-performing peers on narrative retells, and did not demonstrate differences from these peers on personal story generation, expository retells, or narrative writing (Petersen et al., 2022).

Summary of Basic Intervention Principles

The SLP has an important role in collaborating with other educational professionals to ensure that school-aged children achieve academic and social/emotional success. This goes beyond merely working with children who are diagnosed with speech and language disorders. SLPs play an important part in helping to design curriculum in a manner that is accessible to all students, including those with disorders. SLPs should collaborate with teachers and other professionals to ensure that appropriate accommodations are provided to students who need them. Intervention for children with language disorder should relate to the academic curriculum in order to ensure academic success.

The remainder of this chapter discusses goal-writing, evidence-based practice, and interventions for morphosyntax, semantics, and pragmatics. Although the specific intervention methods are divided by language area, it should be noted that some intervention methods target multiple areas of language.

References

Aunola, K., Leskinen, E., Lerkkanen, M. K., & Nurmi, J. E. (2004). Developmental dynamics of math performance from preschool to grade 2. Journal of educational psychology, 96(4), 699.

Cowan, R., Donlan, C., Newton, E. J., & Llyod, D. (2005). Number skills and knowledge in children with specific language impairment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97(4), 732.

Fang, Z. (2005). Scientific literacy: A systematic functional linguistics perspective. Science Education, 89, 335-347.

Harlaar, N., Kovas, Y., Dale, P., Petrill, S., & Plomin, R. (2012). Mathematics is differentially related to reading comprehension and word decoding: Evidence from a genetically sensitive design. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104, 622-635.

Karasinski, C. (2016). Comprehension of narratives, non-fiction, and complex syntax as predictors of science achievement. Speech, Language, and Hearing, 19(4), 203-210. doi: 10.1080/2050571X.2016.118.

Kleemans, T., Segers, E., & Verhoeven, L. (2012). Naming speed as a clinical marker in predicting basic calculation skills in children with specific language impairment. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 33, 882-889.

Koponen, T., Salmi, P., Eklund, K., & Aro, T. (2012). Counting and RAN: Predictors of arithmetic calculation and reading fluency. Journal of Educational Psychology, Advance online publication. doi: 10.1037/a0029285

National Governors Association Center for Best Practices, Council of Chief State School Officers. (2010a) Common Core State Standards . National Governors Association Center for Best Practices, Council of Chief State School Officers, Washington D.C.

National Governors Association Center for Best Practices, Council of Chief State School Officers. (2010b) Common Core State Standards: Mathematics. National Governors Association Center for Best Practices, Council of Chief State School Officers, Washington D.C.

National Governors Association Center for Best Practices, Council of Chief State School Officers. (2010c) Common Core State Standards: English Language Arts. National Governors Association Center for Best Practices, Council of Chief State School Officers, Washington D.C.

National Research Council. (2012). A Framework for K-12 Science Education: Practices, CrosscuttingConcepts, and Core Ideas. Committee on a Conceptual Framework for New K-12 Science Education Standards. Board on Science Education, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Olswang, L. B., & Bain, B. A. (1991). When to recommend intervention. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 22(4), 255-263.

Owens, R.E. (2014). Language disorders: A functional approach to assessment and intervention. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Allyn & Bacon.

Paul, R., Norbury, C., & Gosse, C. (2017). Language disorder from infancy through adolescent.

Petersen, D., Staskowski, M., Spencer, T., Foster, M., & Brough, M. (2022). The effects of a multitiered system of language support on kindergarten oral and written language: A large-scale randomized controlled trial. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 53, 44-68.

Shanahan, T., & Shanahan, C. (2008). Teaching disciplinary literacy to adolescents: Rethinking content area literacy. Harvard Education Review, 78, 40–59.

Shanahan, T., & Shanahan, C. (2012). What is disciplinary literacy and why does it matter? Topics in Language Disorders, 32, 7-13.

Spencer, T. D., & Petersen, D. B. (2012). Story Champs: A multi-tiered language intervention program. http://www.languagedynamicsgroup.com