10 Formal Testing

It is critical to note that diagnosis of a developmental language disorder should never be based solely on the results of standardized testing. All of the aspects of a functional language assessment are critical to the accurate diagnosis and formulation of treatment plans. Similarly, goals should not be written simply to align with items missed on standardized tests; rather, they should align with academic standards and the functional needs of the child. A number considerations must be made in the selection of the appropriate standardized test to administer to a given child. These include the psychometric properties, types of scores, and purpose of the test.

Psychometric properties

When selecting a formal test to administer, it is important to review the test manual carefully in order to ensure that the test has strong psychometrics, as not all published tests do. McCauley and Swisher (1984) provided a list of criteria for evaluating standardized tests. These criteria, as updated by Friberg (2010) are listed below.

- Purpose of the tool is clearly identified

- Examiner qualifications are explicitly stated

- Administration procedures are clearly stated

- An adequate standardization of at least 100 participants is used

- The standardization sample is clearly defined, including information about

- o Geographic representation

- o Gender distribution

- o Socioeconomic status

- o Ethnic background

- o Age distribution

- o Presence/absence of disorders

- Evidence of item-analysis is provided

- Measures of central tendency are noted

- Concurrent validity is documented

- Predictive validity is documented

- Test-retest reliability is reported, with a correlation coefficient of at least .90

- Inter-rater reliability is reported, with a correlation coefficient of at least .90

Reliability

Reliability refers to the repeatability of a result. There are multiple types of reliability. Test-retest reliability suggests that an individual will get the same score on an assessment if the test is repeated. Split-half reliability measures the internal consistency of a test. Typically, this is assessed by comparing the score on the even numbered items with the score on the odd-numbered items. Some tests have multiple forms, which allows re-testing to occur within a shorter interval than needed for a test with only one form. Alternate forms reliability suggests that the same score will be earned, regardless of which form is used. Interrater reliability indicates that a child would earn the same score on a given test, regardless of who administered or scored the test. Intrarater reliability indicates that the same administrator or score would arrive at the same score if scoring the same administration multiple times. Rater reliability can be impacted by a number of factors. One factor that impacts rater reliability is the clarity of directions in the test manual. Manuals should provide clear criteria for scoring with a variety of examples. Complex responses tend to be rated less reliably than simple responses; for example, it is easier to score a point or a single-word answer than to score a response requiring a sentence-level response, such as providing a definition.

Validity

Validity refers to a test measuring what it purports to measure. In order to be valid, a test must be reliable. However, a test can be reliable, without being valid. A test could yield the same score regardless of administrator or scorer, or from the same scorer multiple times, but may not truly measure what it endeavored to measure. Historically, multiple types of validity have been described and will be described here. Face validity suggests that a test appears to measure what it aims to measure. Content validity is established when a panel of experts reviews a test and determines that the test measures what it endeavors to assess. A test has criterion validity when scores on the test are similar to the scores on other measures of the same construct. Criterion validity can be predictive, meaning the score on the test predicts the score on a different measure, to be administered in the future, or concurrent, meaning the score on the test matches the score of another test given at the same time. Construct validity indicates that a test is rooted in theory. Of note, Daub and colleagues (2021) have suggested that these descriptions are actually of types of validity evidence, rather than types of validity, and argue that validity refers to the appropriateness of decisions, so can not be divided into types.

A test can be reliable without being valid, but a valid measure will also be reliable. Figure 1 depicts the relation between reliability and validity.

Validity Framework

Daub and colleagues (2021) have recommended that SLPs adopt a conceptual validity framework, which will be described here. The three key concepts that underlying this framework are

- validation refers to decisions that are made, not tests themselves;

- collecting and evaluating validity evidence is an iterative process; and

- there are types of evidence, not types of validity

(p. 1895).

Identify the clinical decision

The first step in Daub and colleagues’ validity framework is to identify the clinical decision the SLP plans to make using a test score. SLPs need to select tests based on their appropriateness for making the intended decision. Examples of decisions an SLP might make using a test score include diagnosing a disorder, measuring progress, or determining severity.

Identify the necessary evidence to support the decision

The second step in the validity framework is identifying the evidence needed to support the intended decision. If the decision will be diagnosis, test must have evidence of diagnostic accuracy, a normative sample that reflects the child taking the test, accurate measurement of relevant skills for the diagnosis, and evidence of consistency for measuring a child’s ability. If the test is being used to decide whether a child has made significant progress over time, the test must be sensitive to changes in ability, provide a consistent estimate of ability, measure the ability targeted in intervention, and include a test development sample that reflects the child. To use a test to determine severity, the test needs to be sensitive to differences in level of impairment, have an appropriate comparison sample, provide consistent estimates of ability, and broadly measure the skills impacted by a disorder.

Evaluate the evidence

The last step in the valid framework is evaluating the evidence. Because the evidence needed is based on the clinical decision, SLPs do not need to evaluate all of the evidence in the test, they only need to evaluate the evidence required for making the intended decision.

To ascertain whether a test accurately classifies individuals with and without a disorder, measures of diagnostic accuracy are needed. Diagnostic accuracy is discussed below. To evaluate the appropriateness of a normative sample, the SLP should ensure that the demographic characteristics of the test development sample are an appropriate match for the child’s demographics. To ensure that the test measures relevant skills, the SLP should look in the manual for evidence that the questions have been reviewed by content experts and cover all relevant domains; scores are associated with scores on other measures of the same ability and not associated with scores on measures of abilities that do not relate to the underlying skill; and there should be factor analysis or structural equation modeling that reveals the same number of factors or latent variables as the skills the test purports to measure. If a test provides consistent estimates of a person’s ability, there should be detailed administration properties and evidence of test-retest, alternate forms (if applicable), interater, and split-half reliability as well as a low standard error of measurement.

In addition to the sources of evidence needed for determining whether a test accurately classifies children as having or not having a disorder, when assessing change over time, item-response-theory-derived analyses are useful. These analyses may be used to create growth scale values, which are more sensitive that standard scores and percentile ranks to changes in skills after intervention. Criterion-referenced tests, which measure specific skills, may also be useful for assessing changes over time.

When using tests to determine severity, in addition to the sources of evidence noted above for determining the presence or absence of a disorder, evidence that test scores are linearly predicted by severity ratings, such as via correlations between severity levels determined by a gold standard and test scores are useful. Instead of diagnostic accuracy for the presence or absence of a disorder, to use a test to determine severity, there should be diagnostic accuracy for classifying individuals into levels of severity. The demographic characteristics of the norming sample are important, and should include individuals with a range of severity of impairments.

Summary of validity framework

Using the Daub and colleagues’ framework can help SLPs select the best test to use for a given student. It is critical to use the appropriate instrument to obtain the data needed to make accurate clinical decisions.

Diagnostic accuracy

Surprisingly, diagnostic accuracy has been discussed for a relatively short time in the field of SLP. Diagnostic accuracy can be measured in terms of sensitivity and specificity, likelihood ratios, and predictive values (Dollaghan, 2004). Sensitivity refers to the degree to which a test identifies individuals who do have a disorder as having the disorder; in other words, sensitivity refers to identifying “true positives.” Specificity is the degree to which a test identifies individuals without a disorder as not having the disorder; in other words, specificity refers to identifying “true negatives.” Positive likelihood ratio is the degree of confidence that an individual is a true positive, or has the disorder if identified as such. LR+=sensitivity/(1-specificity). Negative likelihood ratio is the degree of confidence that an individual is a true negative, or does not have the disorder if identified as not having the disorder. LR-=(1-sensitivity)/specificity. Positive predictive value is the probability that an individual with a positive test result has the disorder, or the probability that an individual is a true positive. PPV=true positives/true positives + false positives. Negative predictive value is the probability that an individual with a negative test result does not have the disorder, or is a true negative. NPV=true negatives/true negatives + false negatives.

Scores

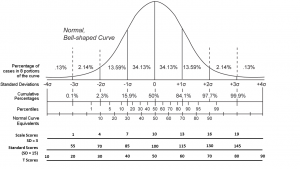

Often, standardized tests of language ability are norm-referenced, meaning that they can be used to compare the scores of an individual child to those of age-matched and/or grade-matched peers. Typically, these tests yield raw scores, which may be a count of correct or incorrect items, which convert to scaled scores, standard scores, and percentile ranks. These scores are based on the normal curve. Scaled scores have a mean of 10 and a standard deviation of 3, so the typical range is 7-13. Standard scores have a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15, with a typical range of 85-115. Percentile ranks have a mean of 50. Percentile scores indicate the portion of the normative sample earned a lower score than a given individual. Percentile ranks, unlike standard scores and scaled scores, do not represent equal intervals. In a normal curve, 68% of scores fall within one standard deviation of the mean, and 96% fall within two standard deviations of the mean. The standard deviation is the average difference of scores from the mean. Figure 2 depicts the normal curve and associated scores.

Although state legislation may have specific cutoffs for qualifying children to receive services for language disorders in schools, Spaulding, Szulga, & Figueroa (2012) found that the cutoff scores that best differentiate children with disorders from those with typical language ability vary among tests. Tests also report equivalence scores, such as age-equivalents or grade-equivalents. I advise against using these scores. If you are working for an agency that requires them, you should explain why they are not appropriate for determining the presence or absence of a disorder. An equivalent score is the median score earned by the individuals of a particular age or grade in the normative sample. These scores do not represent normal variation. They also do not represent equal intervals. When a child earns a particular age-equivalent score, this does not mean that the child’s communication is just like the communication of children who are that age. It only means that the child earned the median score of children that age in the normative sample. Although many test manuals specifically caution against using age-equivalents for eligibility determinations, these scores are still used for this purpose, which is not appropriate. Children could earn age-equivalent scores that are lower than their chronological ages, but the standard scores could be within the typical range.

Standardized tests have advantages, including being easy to administer and score, and (ideally, but be certain to review the test manual) having high reliability, validity, and diagnostic accuracy. Policymakers and funders may favor the availability of quantitative data. However, standardized tests do have drawbacks. They are rigidly administered, often with explicit directions dictating the exact words that the clinician uses. It is possible that a child might be able to answer a question correctly with slightly different wording, but wording changes may not be permitted according to the test directions. Test directions also tend to specify that the examiner provide no feedback to the examinee regarding the correctness of a response. The administration of these tests does not demonstrate typical pragmatics; instead of responding contingently to an examinee, the examiner usually just records the response and then asks an unrelated question. Dynamic assessment can be used in conjunction with standardized measures to help to address some of these drawbacks.

Purpose of test

There are many standardized tests available for a variety of purposes. Selecting the test that matches the purpose of the assessment is critical. Reviewing referral information and completing informal observations prior to selecting a standardized test to administer is helpful in the selection process. The information gleaned from these practices will provide insight into the areas needing further assessment.

A number of standardized tests are considered “omnibus” measures; that is, they assess a variety of language domains, often using multiple subtests. Examples of omnibus measures include the Assessment of Literacy and Language (ALL; Lombardino et al., 2005), Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals–Fifth Edition (CELF-5; Wiig et al., 2013), the Oral and Written Language Scales–Second Edition (OWLS-2; Carrow-Woodfolk, 2011), the Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language–Second Edition (CASL-2; Carrow-Woodfolk, 2017), the Test of Language Development-Primary: Fifth Edition (TOLD-P:5; Newcomer & Hammill, 2019), the Test of Language Development-Intermediate:Fifth Editon (TOLD-I:5; Hammill & Newcomer, 2019), and the Test of Integrated Language and Literacy Skills (TILLS; Nelson et al., 2015). The ALLs, OWLS-2 and the TILLS include the assessment of literacy skills in addition to oral language skills. Two omnibus assessments that have been shown to have strong psychometric properties are the CELF-5 and the ALL (Denman et al., 2017).

Other standardized tests are available for assessing specific aspects of language. For example, the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Fifth Edition (PPVT-5; Dunn, 2019) and the Receptive One Word Picture Vocabulary Test-Fourth Edition (ROWPVT-4; Martin & Brownell, 2010) assess receptive vocabulary. The Expressive Vocabulary Test-Third Edition (EVT-3; Williams, 2018) and the Expressive One Word Picture Vocabulary Test-Fourth Edition (EOWPVT-4, Martin & Brownell, 2010) evaluate expressive vocabulary. The Test of Word Finding-Third Edition (TWF-3; German, 2014) assesses word-finding ability. The Rice Wexler Test of Early Grammatical Impairment (TEGI, Rice & Wexler, 2001) and the Structured Photographic Expressive Language Test-Third Edition (SPELT-3; Dawson & Stout, 2003) assess morphosyntax.

Omnibus measures are often administered in order to identify strengths and areas for growth (Ogiela & Montzka, 2021). Tests of a specific domain can be useful for confirming deficits in a given area. It can also save time to use an assessment of a specific domain of language if no deficits are noted in other areas based on referral information, observations, and language sampling. SLPs should ensure that assessment of the other language domains has been conducted via these other parts of the comprehensive assessment if standardized measures are not administered for this purpose.

Surprisingly, SLPs are more likely to complete follow-up testing on semantics, especially single-word vocabulary, rather than on morphosyntax (Ogiela & Motzka, 2021). Although morphosyntax is addressed in omnibus tests, typically subtests do not have enough exemplars of specific structures to provide a full picture of a child’s degree of difficulty and patterns of difficulty in this domain of language. Given the notable deficits in morphosyntax in children with DLD, clinicians should consider administering tests that probe more deeply into this aspect of language (Ogiela & Montzka, 2021). If clinicians are not probing morphosyntactic deficits via additional standardized testing, they should be using observations, language sample analysis, and information from parents and teachers, including samples of classroom work, in order to ensure that they have thoroughly assessed this area.

Tests for Social Communication

Pragmatics, or social communication, can be challenging to evaluate via standardized measures. The administration of standardized tests often does not comply with typical social norms, such as contingent responding. Often, the examiner asks a question, the child answers it, and the examiner asks a new, unrelated question. There is no or little expansion on one another’s responses. This is different from the back-and-forth of a typical conversation. Another reason that evaluating social communication via standardized tests is difficult is that, at times, children can accurately respond to items on tests endeavoring to measure social communication, such as those asking for an appropriate response to a given scenario, but they do not provide these responses in real-life situations.

There are a number of tests that assess social communication, including the Clinical Assessment of Pragmatics (CAPS; Hamaguchi & Ross-Swain, 2015), Social Emotional Evaluation (SEE; Wiig, 2008), the Social Language Development Test–Adolescent: Normative Update (SLDT-A:NU; Bowers et al., 2017), Social Language Development Test–Elementary: Normative Update (SLDT-E:NU; Bowers et al., 2016),and the Test of Pragmatic Language–Second Edition (TOPL-2; Lavi, 2019).Many omnibus measures of language include subtests that evaluate social communication, such as the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals–Fifth Edition Metalinguistics (CELF-5 Metalinguistics; Wiig & Secord, 2014), Diagnostic Evaluation of Language Variation–Norm Referenced (DELV-NR; Seymour et al., 2005), RESCA-E, CELF-5 (Wiig et al., 2013), CASL–2 (Carrow-Woodfolk, 2017), TILLS (Nelson et al., 2015), OWLS-2 (Carrow-Woodfolk, 2011). No single or subtest has been found to be ideal for evaluating social communication (Timler & Covey, 2021). In the absence of a “gold standard,” Timler and Covey (2021) recommend that if an SLP needs a standardized test to evaluate a child’s social communication, the select the test that meets the most of the following criteria for a given child.

- The description of the clinical group in comparison studies matches the child’s profiles.

- The mean group difference between the child’s clinical group and the typically developing group is at least 1 standard deviation.

- If diagnostic accuracy is reported, the description of the clinical group in the diagnostic accuracy section (if different than the group in the comparison studies) matches the child’s profile.

- If reported, sensitivity and specificity levels are at or above 80% for a specific cut score.

- If reported, positive likelihood valuate are at or greater than 10 and negative likelihood values are less than 0.10.

- The tests includes items that align with concerns reported by parents and teachers.

Other measures, including language sampling, observations, and information from referral sources, such as parents and teachers, tend to be superior to standardized tests for obtaining a picture of the child’s social communication. Even if a standardized test is used to evaluate social communication, the aforementioned measures need to be included in the assessment.

Summary

Standardized tests are a useful part of the assessment of language. The provide the ability to compare the child’s language to a normative sample, and often provide scores that are easy for interprofessional colleagues, parents, and funders to understand. Once a clinician has practiced administering a particular test, administration tends to be fairly easy. Despite these advantages of standardized tests, is vital to remember that these measures are part of the assessment process, and do not constitute a comprehensive assessment when administered in the absence of the other parts of the assessment process. Clinicians also need to keep in mind the purpose of test administration in order to ensure that they are selecting the most appropriate measure for an individual child.

References

Bowers, L., Huisingh, R., & LoGiudice, C. (2016). The Social Language Development Test–Elementary: Normative Update (SLDT-E: NU). LinguiSystems.

Bowers, L., Huisingh, R., & LoGiudice, C. (2017). The Social Language Development Test–Adolescent: Normative Update (SLDT-A: NU). LinguiSystems.

Carrow-Woolfolk, E. (2011). Oral and Written Language Scales, Second Edition (OWLS-II). Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services.

Carrow-Woolfolk, E. (2017). Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language, Second Edition (CASL-2). Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services.

Daub, O., Cunningham, B. J., Bagatto, M. P., Johnson, A. M., Kwok, E. Y., Smyth, R. E., & Cardy, J. O. (2021). Adopting a conceptual validity framework for testing in speech-language pathology. American journal of speech-language pathology, 30(4), 1894-1908.

Dawson, J., Stout, C., & Eyer, J. (2003). The Structured Photographic Expressive Language Test—Third Edition. Dekalb, IL: Janelle Publications.

Denman, D., Speyer, R., Munro, N., Pearce, W. M., Chen, Y. W., & Cordier, R. (2017).=Psychometric properties of language assessments for children aged 4–12 years: Asystematic review. Frontiers in psychology, 8, 1515.

Dollaghan, C. (2004). Evidence-based practice in communication disorders: What do weknow, and when do we know it? Journal of Communication Disorders, 37(5), 391-400.

Dunn, L. M., & Dunn, D. M. (2019). Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test–Fifth Edition (PPVT-5). Pearson.

Friberg, J. (2010). Considerations for test selection: How do validity and reliability impact diagnostic decisions? Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 26(1), 77-92.

German, D. J. (2014). Test of Word Finding—Third Edition. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

Hamaguchi, P., & Ross-Swain, D. (2015). Receptive, Expressive & Social Communication Assessment–Elementary (RESCA-E). Academic Therapy Publications.

Hammill, D., & Newcomer, P. (2019). Test of Language Development–Intermediate: Fifth Edition. Pro-Ed.

Lavi, A. (2019). Clinical Assessment of Pragmatics (CAPs) [Manual]. Western Psychological Services.

Lombardino, L. J., Leiberman, R., and Brown, J. C. (2005). Assessment of Literacy and Language. San Antonio, TX: Pearson Psychcorp.

Martin, N. (2013a). Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test–4: (EOWPVT-4). Academic Therapy Publications.

Martin, N. (2013b). Receptive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test–4: (ROWPVT-4). Academic Therapy Publications.

McCauley, R.J., & Swisher, L. (1984) Psychometric review of language and articulation tests for preschool children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders 49: 34–42.

Nelson, N., Plante, E., Helm-Estabrooks, N., & Holz, G. (2015). Test of Integrated Language and Literacy Skills (TILLS). Brookes.

Newcomer, P., & Hammill, D. (2019). Test of Language Development–Primary: Fifth Edition. Pro-Ed.

Ogiela, D. A., & Montzka, J. L. (2021). Norm-referenced language test selection practices for elementary school children with suspected developmental language disorder. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 52(1), 288-303.

Phelps-Terasaki, D., & Phelps-Gunn, T. (2007). Test of Pragmatic Language–Second Edition (TOPL-2). The Psychological Corporation.

Plante, E., & Vance, R. (1994). Selection of preschool language tests: A data-based approach. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 25(1), 15-24.

Rice, M., & Wexler, K. (2001). Rice/Wexler Test of Early Grammatical Impairment. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas. Retrieved from https://cldp.ku.edu/rice-wexler-tegi

Seymour, H., Roeper, T., de Villiers, J., & de Villiers, P. (2005). Diagnostic Evaluation of Language Variation–Norm Referenced (DELV-Norm Referenced). The Psychological Corporation. [Republished 2018, Sun Prairie, WI: Ventris Learning].

Spaulding, T. J., Szulga, M.S., & Figueroa, C. (2012). Using norm-referenced tests to determine severity of language impairment in children: Disconnect between U.S. policymakers and test developers. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 43, 176-190.

Timler, G. R., & Covey, M. A. (2021). Pragmatic language and social communication tests for students aged 8–18 years: A review of test accuracy. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 6(1), 18-38.

Wiig, E. (2008). Social Emotional Evaluation (SEE). Super Duper. Wiig, E., & Secord, W. A. (2014). Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals–Fifth Edition Metalinguistics (CELF-5 Metalinguistics). Pearson Psych Corp.

Wiig, E. H., Secord, W. A., & Semel, E. M. (2013). Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals–Fifth Edition. Bloomington, MN: Pearson.

Williams, K. T. (2018). Expressive Vocabulary Test–Third Ediition (EVT-3). AGS.