13 Introduction to Intervention and Evidence-Based Practice

Best practices in speech-language pathology (SLP) intervention involve engaging in evidence-based practice. The principles of evidence-based practice will be discussed in this chapter.

Evidence-Based Practice

The concept of evidence-based practice (EBP) emerged from evidence-based medicine, defined in 1992 by the Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. The assumptions of evidence-based medicine are that

- clinical experience and the development of clinical judgement are critical in practice; the study of basic mechanisms is necessary, but alone is not enough to guide clinical practice; and

- the understanding of rules of evidence is needed to interpret the literature on etiology, prognosis, assessment, and treatment.

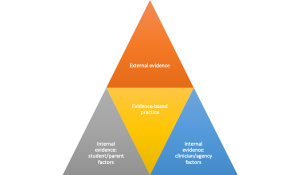

A number of definitions have surfaced as additional health professions have adopted EBP. The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) defines EBP as the integration of clinical expertise/expert opinion, external scientific evidence, and client/patient/caregiver perspectives (ASHA, 2005). ASHA has provided a number of resources to help clinicians implement EBP, which can be found here. Gillam and Gillam (2006) outlined the EBP process, which consists of seven steps: framing the clinical question, finding the external evidence, determining the level of evidence and critically evaluating the studies, evaluating the internal evidence related to student and parent factors, evaluating the external evidence relating to clinician and agency factors, making the clinical decision, and evaluating the outcomes of the clinical decision.

Clinical questions are typically formed using the “PICO” framework. This stands for population, intervention, comparison, outcome. Population refers to the characteristics of the clients. This can include age, diagnosis, severity level, gender, socioeconomic status, or error types. Intervention refers to the screening, assessment, treatment, or service delivery model the clinician is considering. Comparison refers to an alternative to the intervention. Outcome refers to your ultimate measure, or what you aim to achieve.

The next step in the EBP process is finding the evidence. This can be done using well-defined search terms, which may need to be narrowed or broadened, based on your results. You can search specific databases, such as ASHAWire, speechBITE, PubMed, PsycNet, ERIC, or JSTOR, or you can use more general databases, which are free to the general public, such as MEDLINE or GoogleScholar. In addition to finding articles detailing single studies, synthesized evidence can be found. Using synthesized evidence saves time because this type of evidence complies the results of multiple studies. Systematic reviews are articles that synthesize the results of multiple studies on a given topic. Meta-analyses are a type of systematic review that use statistical analyses to draw conclusions across studies, and are particularly useful. Another type of synthesized evidence is clinical practice guidelines, which can be evidence-based from the results of a systematic review, or consensus-based from agreement among experts. ASHA’s Evidence Maps, found here are a source of synthesized evidence.

Once you have located a study, you need to assess the relevance, level of evidence, and quality of the study. The following paragraphs describe this process.

The hierarchy of five levels of evidence has been described by a number of groups (e.g., Deerholt, Dang, and Sigma Theta Tau International, 2012; Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, 2009). These levels are ranked in order from highest to lowest.

- Level 1 includes systematic reviews of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) or single RCTs.

- Level 2 consists of quasi-experimental studies or systematic reviews of quasi-experimental studies, or a combination of RCTs and quasi-experimental studies.

- Level 3 is comprised of non-experimental studies, qualitative studies, or systematic reviews of non-experimental studies, or a combination of RCTs, quasi-experimental studies, or non-experimental studies.

- Level 4 refers to single case studies.

- Level 5 is expert opinion.

Trochim (2020) provides the following guidance in order to determine the study design. First, if random assignment is used, the study is an RCT. If random assignment is not used, if there is a control group, the study is quasi-experimental, if there is no control group, the study is non-experimental.

The fourth EBP step is evaluating the internal evidence that relates to child and family factors. This includes considering their preferences, such as whether the child prefers large or small groups, or within or outside the classroom treatment. The extent to which a parent is willing or able to be involved in treatment can impact the treatment methods, as well. Gillam and Gillam (2006) suggest that the following child and family factors be considered, listed here from the most highly weighted to the lowest weighted: cultural values and beliefs, inclusion of activities the student enjoys and finds motivating, financial resources needed, amount of participation that will be required by the student and family, and student and family opinions. When student and family opinions or preferences conflict with external evidence, the clinician should provide information about what the external evidence indicates.

Next, you need to evaluate the internal evidence related to clinician and agency factors. For example, if a method of intervention involves treatment five days per week, and the clinician is only in the child’s school three days weekly, this method may not be an appropriate option. If a method of intervention requires the purchase of costly materials for which there are no funds, other methods will need to be considered. Gillam and Gillam (2006) suggest the following order of weighting for clinician and agency factors. The first clinician and agency factor to be considered is the clinician’s knowledge of and ability to implement an intervention. Financial resources and agency policies are additional considerations. Clinicians can use their data from other students, which may be considered consistent with external research evidence from single case studies, to influence clinical decisions. Clinician’s theoretical perspectives also can be considered in the process of making decisions.

The sixth step in the EBP process is integrating the internal and external evidence to make a decision. The three pillars of EBP, external evidence, clinician-agency factors, and client-family factors must each be considered in order to make the optimal decision. The final step in the process is evaluating the outcomes of your decision. If using standardized tests to assess progress, Gillam and Gillam (2006) recommend using confidence intervals. They suggest that a clinician can consider a child to have made noticeable gains if the posttest score falls three or more points above the upper limit of the 95% confidence interval.

Feedback

There is a growing body of evidence that suggests the efficacy of errorless learning for children with developmental language disorder (DLD) (Arbel et al., 2020). Errorless learning involves preventing the student from giving incorrect answers by providing the prompts necessary to elicit the correct answer. Committing errors can result in making inaccurate associations, even when feedback is given. Processing feedback may be challenging for children with DLD, due to impairments in language processing, executive functioning, and working memory, so feedback may not be beneficial for them. When feedback is given, positive feedback is more beneficial than negative feedback, although feedback-free learning environments may be the most beneficial (Arbel et al., 2020).

References

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2005). Evidence-based practice in communication disorders [Position Statement]. Available from www.asha.org/policy.

Arbel, Y., Fitzpatrick, I., & He, X. (2021). Learning with and without feedback in children With developmental language disorder. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 64(5), 1696-1711. https://doi.org/10.1044/2021_JSLHR-20-0049

Dearholt, S., Dang, Deborah, & Sigma Theta Tau International. (2012). Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-based Practice : Models and Guidelines.

Gillam, S. & Gillam, R. (2006). Making evidence-based decisions about child language intervention in schools. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 37, 304-315.

Owens, R.E. (2014). Language disorders: A functional approach to assessment and intervention. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Allyn & Bacon.

Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. (2009). Levels of evidence and grades of recommendation. Retrieved March 10, 2020, fromhttps://www.cebm.net/2009/06/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-evidence-march-2009/

Trochim, W. (2020). Research methods knowledge base. Retrieved from https://socialresearchmethods.net/kb/research-design-types/ on March 17, 2020.