14 Goal-Writing

Kamhi (2014) and Diehm (2017) highlight the importance of goal-writing in the treatment of children with language-learning disorders, suggesting that goal-writing is one of the most important aspects of intervention. Most SLPs recognize the importance of goal-writing, but many still find this a challenging aspect of clinical practice. Diehm emphasizes the importance of individualizing goals, rather than merely relying on “goal banks” provided by software designed to prepare Individualized Education Programs (IEPs). She also cautions against writing goals that closely resemble items on standardized tests, as this may invalidate future administrations of that test and may not result in academic success. Instead, SLPs should align goals to educational standards. In order to do so, Diehm suggests considering the knowledge and skills the students need to master a given standard, and using this information to write the goals.

SMART is a format often used in goal-writing. This acronym was first used in the business field in the early 1980s, began appearing in the therapy literature in the 1990s, and was suggested as an appropriate framework for IEP goal-writing in the late 2000s (Nobriga & St. Clair, 2018). SMART stands for Specific, Measureable, Attainable/Achievable, Relevant, and Timely. Diehm (2017) provides a tutorial for SLPs to ensure that their goals are SMART.

If a goal is specific, others reading the IEP will know what the student should do, in what context, with what materials, and with what help from someone else (e.g., the SLP or a parent). A specific goal contains a verb that represents an observable behavior. For example, rather than identify, a clinician might use point to. A specific goal should include one target behavior. If a goal contains multiple behaviors, it can be difficult to ascertain whether or not the goal has been met. Torres (2013) suggests asking the following questions when writing a goal that is specific.

- What are the student’s strengths?

- What are the student’s areas for growth?

- What skills contribute to the student’s strengths?

- What skills are needed to improve the areas for growth?

- What skills can the student use to compensate for deficits?

- What skills are needed that the SLP can help the student attain?

- What should be addressed first? Why?

- What tasks will the student complete to work on the skill?

- What supports will be provided?

A measurable goal must include an observable behavior (as noted in describing specific goals), the level of support to be provided (as noted in describing specific goals), criteria, and the conditions under which the student will perform the behavior. The criteria need to make sense within the context of the goal. Percent accuracy is often used as criteria, which makes sense in a number of contexts. However, other criteria, such as frequency of a behavior or duration of a behavior, may be better criteria for measuring some targets. Torres (2013) recommends using the following questions to help ensure that a goal is measurable.

- Can you define the skill that will determine whether or not the student is meeting the target, and can the progress of that skill be measured?

- How will progress be measured?

- When you consider the goal accomplished?

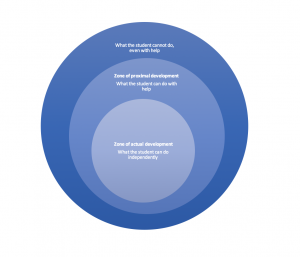

When considering an attainable/achievable goal, if working in a school and writing an IEP, a period of one year is the typical timeframe, as IEPs are re-written annually. In order to determine the attainability of a goal, consider clinical experience with students with similar profiles, the research literature, and collaboration with other professionals (Diehm, 2017). Also consider the amount of support the child currently needs to help determine whether or not the child is likely to attain the goal. Typically, a goal within the child’s zone of proximal development, or what the child can do with support (Vygotsky, 1978), is considered achievable, whereas working on a target that the child does not perform even with support, may not be achievable, or may need to be written as something the child will do with support, albeit less support than is needed at baseline.

Relevant goals should relate to educational standards. Including the specific standard to which the goal relates within the goal can help to highlight the relevance. A relevant goal also could be a goal that addresses an underlying skill needed to meet an educational standard or multiple educational standards. Torres suggests the following questions as a guide to writing relevant goals.

- Will achieving this goal serve a communicative function for the student, rather than just being something you can do with the student?

- Will this goal serve a purpose in the student’s life, considering the child’s diagnosis and social and cultural needs?

- Does the goal meet educational standards?

Timely refers to the amount of time in which the child is expected to meet the goal. As noted in describing attainable/achievable goals, this is typically written as one year in schools. It may be appropriate to have a shorter timeframe for some goals, especially those for which the child is stimulable, or can do with help.

Despite learning the SMART framework during their graduate studies, many SLPs continue to experience challenges when writing goals (Nobriga & St. Clair, 2018). Nobriga and St. Clair developed a flowchart that can help clinicians overcome these challenges. Using this framework, the clinician first asks, “What is the behavior you want to teach?” Once the behavior is identified, the clinician ensures that the behavior is client appropriate, considering culture, functionality, and client and family preferences. Next, the clinician confirms that the behavior is specific. The clinician then ensures that the behavior is observable. The next consideration is that the behavior is within the client’s zone of proximal development; that is, that the client can perform the behavior with help or scaffolding. Finally, the clinician determines whether or not the behavior is singular; that is, that it should not be imbedded or implied. If the behavior is not singular, but the client is ready to perform multiple skills simultaneously, the behavior could still be acceptable.

Goals should be constructed in collaboration with the student, family, and other professionals involved with the student. Regular education teachers can provide insight into what the student needs to be able to do in the classroom. Family members offer information regarding to what communication behaviors will benefit the student in the home and community. Students themselves should have the opportunity to give input into their own goals in order to ensure that the behaviors targeted will help the student feel more successful in academic and social situations.

References

Diehm, E. (2017). Writing measurable and academically relevant IEP Goals with 80% accuracy over three consecutive trials. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, Sig 16, 2, 34-44.

Kamhi, A. (2014). Improving clinical practices for children with language and learning disorders. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 45, 92-103.

Nobriga, C., & St. Clair, J. (2018). Training goal writing: A practical and systematic approach. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, SIG 11, 3( 1), 36-46.

Torres, I. (2013, September 9). Tricks to take the pain out of writing treatment goals. ASHA Leader Live. Retrieved from https://leader.pubs.asha.org/do/10.1044/tricks-to-take-the-pain-out-of-writing-treatment-goals/full/.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind and society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

what an individual can do with support