1 Defining Language Disorder

Language disorders are heterogeneous disorders that can be acquired or developmental. They are characterized by deficits in the comprehension and/or production of spoken and/or written language in any combination of deficits of form, content, and use (Owens, 2012). There has been debate in the field of speech-language pathology regarding terminology to use in discussing language disorders. For a number of years, the term specific language impairment (SLI) was used in the research literature to describe the language deficits of children with intact nonverbal cognition. However, given the evidence that many children with language deficits exhibit subtle deficits in the cognitive processes described in the previous section of this book, this term was called into question. Current preference, although there are dissenters, is to use the term developmental language disorder (DLD) in reference to language problems that begin in childhood, are likely to persist into and beyond middle childhood, and impact social or educational outcomes (Bishop et al., 2017, McGregor et al., 2020). Typically, the terms SLI or DLD are not used to refer to children with language deficits who are three years old or younger; these children typically are termed late talking toddlers or late talkers because many of these children’s deficits resolve prior to entering school (McGregor et al., 2020). Bishop and colleagues developed 12 consensus statements regarding language disorders, stated below.

- Consistent terminology is important.

- “Developmental language disorder” is proposed for labeling language problems that are likely to persist into and beyond middle childhood and have an effect on academics and social interactions.

- This does NOT refer to a discrepancy between verbal and nonverbal ability

- Prognostic indicators vary with age, but language problems typically persist.

- Prognosis is difficult to ascertain for children under three years of age. Many “late talking toddlers” catch up to their peers. Particular risk factors for persistent language disorders include no word combinations at age 24 months, lack of gestures, lack of imitating body movements, decreased joint attention, and family history language or literacy problems.

- From age three to four years, prediction improves, and the greater number of language areas that are impaired, the greater the likelihood of persistent language disorder. Sentence repetition is a good marker for predicting language outcomes.

- Language problems present at age five years are likely to persist. Prognosis is especially poor in the presence of low receptive language and/or nonverbal ability.

- Children whose home language or first language differs from the language being assessed should not be diagnosed with language disorder unless age-appropriate language ability is not evident in any language.

- This definition of language disorder does not use exclusionary criteria.

- “Differentiating conditions are biomedical conditions in which language disorder occurs as part of a more complex pattern of impairments.” The recommended terminology is “language disorder associated with X;” for example: “Language disorder associated with traumatic brain injury.”

- The term Developmental Language Disorder (DLD) refers to language disorder in the absence of differentiating conditions.

- A child with a language disorder may have low nonverbal cognition. This does not preclude a diagnosis of DLD.

- Co-occurring disorders are cognitive, sensorimotor, or behavioral disorders that may impact the impairment and intervention, but the causal relation to language is not clear. These include problems in attention, emotions, reading, spelling, speech, behavior, and adaptive behavior.

- Risk factors are biological or environmental factors statistically associated with DLD, with unclear causal relations. These risk factors do not preclude a DLD diagnosis.

- Family history

- Being male

- Parents with few years of education

- Being a younger sibling in a large family

- DLDs are heterogenous

- Phonology- Errors of phonological production in the absence of other language deficits do not meet criteria for a diagnosis of DLD. Similarly, deficits in phonological awareness alone would not meet criteria for a diagnosis of DLD, as these deficits may be a result of, rather than a cause of, literacy problems.

- Syntax- Deficits in morphosyntax are common in DLD.

- Word-finding and semantics- Children with DLD may have deficits in word-finding or understanding the meanings of words or combinations of words.

- Pragmatics/language use- Deficits in pragmatics can include providing too much or too little information, insensitivity to social cues, and difficulty understanding figurative language.

- Discourse- Children may have difficulty producing sequences of coherent utterances, or difficulty linking utterances together and making inferences to comprehend the whole meaning.

- Verbal learning and memory- Many children with DLD have difficulty retaining sequences of sounds or words over a short delay or learning to associate words with their meaning.

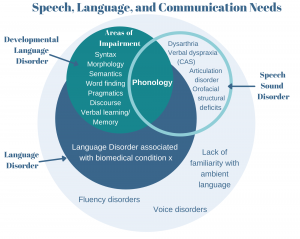

- It can be useful to have a superordinate category for policymakers that includes all children with speech, language, and communication needs. The suggested term is Speech, Language, and Communication Needs (SLCN), as depicted by Figure 2.

Clinical markers

Standardized assessments of language disorder have shown less than ideal diagnostic accuracy (Plante & Vance, 1994); thus, researchers have endeavored to find “clinical markers” of language disorder. Clinical markers refer to measures that yield a bimodal distribution of scores, with low accuracy for individuals with language disorder vs typically developing individuals (Rice & Wexler, 1996). Tense-marking, or use of third person singular –s, past tense –ed, and BE and DO, has been shown to be one potential clinical marker (Conti-Ramsden, 2003; Falcaro et al., 2008; Redmond et al., 2019; Rice & Wexler, 1996), including past tense -ed marking in oral reading (Werfel et al., 2017). Non-word repetition (Conti-Ramsden, 2003, Conti-Ramsden et al., 2001; Dollaghan & Campbell, 1998; Gathercole & Baddeley, 1990) and sentence repetition (Archibald & Joanisse, 2009; Conti-Ramsden et al., 2001; Redmond et al., 2019) also have been identified as clinical markers of language disorder. Nonword repetition measures short-term memory and phonological ability (Chiat, 2015). Sentence repetition involves processing and analyzing the sentence relative to multiple levels of mental representation, including phonological, morphosyntactic, and semantic, extracting the meaning of the sentence, and using the production system to replicate the meaning from activated representations in long-term memory. This involves the simultaneous storage and retrieval that is associated with multiple components of Baddeley’s (2010) model of working memory, including the episodic buffer, the phonological loop, and the central executive (Armon-Lotem & Marinis, 2015). These tasks could be useful to include as screening measures for language disorder (Redmond et al., 2019).

References

Archibald, L. M., & Joanisse, M. F. (2009). On the sensitivity and specificity of nonword repetition and sentence rec

all to language and memory impairments in children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 52, 899-

914.

Armon-Lotem, S., & Meir, N. (2016). Diagnostic accuracy of repe- tition tasks for the identification of specific language impairment (SLI) in bilingual children: Evidence from Russian and Hebrew. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 51(6), 715–731. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12242

Baddeley, A. (2010). Working memory. Current Biology, 20(4), R136-R140.

Bishop, D.V.M., Snowling, M.J., Thompson, P.A., Greenhalgh, T., & the CATALISE-2 consortium. (2017). Phase 2 of

CATALISE: A multinational and multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study of problems with language develop-

ment:Terminology. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(10), 1068-1080.

Chiat, S. (2015). Nonword repetition. In S. Armon-Lotem, J. de Jong, & N. Meir (Eds.), Methods for assessing multilin

gual children: Disentangling bilingualism from language impairment, (pp. 125-150). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Conti-Ramsden, G. (2003). Processing and linguistic markers in young children with specific language impairment (SLI). Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 46(5), 1029-1037.

Conti‐Ramsden, G., Botting, N., & Faragher, B. (2001). Psycholinguistic markers for specific language impairment (SLI). Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 42(6), 741-748.

Dollaghan, C., & Campbell, T. F. (1998). Nonword repetition and child language impairment. Journal of Speech,

Language and Hearing Research, 41, 1136–1146.

Gathercole, S., & Baddeley, A. (1990). Phonological memory deficits in language disordered children: Is there a

causal connection? Journal of Memory and Language, 29, 336–360.

McGregor, K.K., Goffman, L., Van Horne, A.O., Hogan, T.P., & Finestack, L.H. (2020). Developmental language dis-

order: Applications for advocacy, research, and clinical service. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups,

5, 38-46.

Plante, E., & Vance, R. (1994). Selection of preschool language tests: A data-based approach. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 25(1), 15-24.

Redmond, S., Ash, A., Christopulos, T., & Pfaff, T. (2019). Diagnostic accuracy of sentence recall and past tense

measures for identifying children’s language impairments. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research,

62, 2438-2454.

Rice, M. L., & Wexler, K. (1996). Toward tense as a clinical marker of specific language impairment in English-speak-

ing children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 39(6), 1239-1257.