2 Associated Cognitive Processes

A number of cognitive processes are associated with language ability. Children with deficits in language often, though not always, display deficits in other areas, including working memory, executive functioning, attention, and academic performance. At times these deficits related areas are subtle, but their presence can exacerbate the challenges these individuals experience.

Working memory

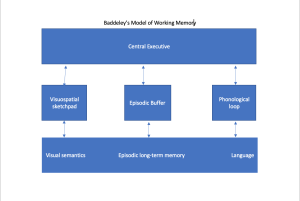

Working memory refers to the system required to hold representations in the mind during the performance of complex tasks (Baddeley, 2010). Baddeley’s model of working memory consists of four separate, interacting systems. The central executive is the attentional control system, which is aided by two short-term storage systems. The phonological loop is responsible for verbal-acoustic stimuli, and the visuo-spatial sketchpad is responsible for visual stimuli. These two storage systems interact with the episodic buffer, which is responsible for perceptual informational and long-term memory. Children with language disorders often display deficits in working memory (Ellis Weismer, Evans, & Hesketh, 1999; Marton & Schwarz, 2003, Montgomery & Evans, 2009) and present with atypical neural substrates for verbal working memory (Ellis Weismer et al., 2005).

The capacity theory of comprehension (Just & Carpenter, 1992) highlights the role of working memory in language comprehension. This theory contrasts with Baddeley’s theory in its exclusion of modality-specific buffers, and corresponds generally to the “central executive” in Baddeley’s theory. The capacity theory of comprehension suggests that each element to be remembered is associated with a level of activation. If the level of activation needed to simultaneously store and process the information exceeds the system’s maximum capacity, information will not be comprehended or will be forgotten. Although some researchers have argued that verbal working memory is not separable from language comprehension tasks (Macdonald & Christensen, 2002), current evidence suggests that working memory contributes to and is highly correlated with language processing but constitutes a separate dimension (Nelson et al., 2022).

Executive functioning

Executive functions are high-level cognitive processes. Miyake and colleague (2000) identified three constructs that fit within the “umbrella term” of executive functions in adults: shifting, updating, and inhibition, Shifting refers to the ability to shift attention between mental sets, tasks, or operations. Differences in the ability to carry out a new operation in spite of proactive interference or negative priming may be at the root of individual differences in shifting ability. Updating refers to the ability to monitor information as it enters working memory, analyze it for relevance to the current task, and modify the contents of working memory by replacing older, less relevant information with information that is newer and more relevant. Active manipulation of relevant information in working memory, rather than merely passive storage, is required for this executive updating and monitoring of working memory representations. Inhibition refers to the ability to consciously inhibit dominant responses. The factors identified as latent variables in adults by Miyake et al. (2000) have emerged as factors in studies of executive functioning in children (Lehto et al., 2003). However, some studies of executive functioning in children have found only shifting and updating (van der Sluis et al., 2007), whereas others have found only updating and inhibition (St. Clair-Thompson & Gathercole, 2006). Language ability and executive functioning may have a reciprocal relationship, with deficits in executive functioning resulting in difficulty using language to modify behaviors, which in turn results in executive functioning deficits (Marlowe, 2000). The relation between EF and language ability may be mediated by nonverbal cognitive ability (Karasinski, 2015).

Children with language disorder have been shown to perform more poorly than children with typical language development on tasks assessing inhibition (Henry et al.., 2012, Im-Bolter et al., 2006) and updating (Im-Bolter et al., 2006). fMRI data have suggested that shifting may be more challenging for children with language disorder than children with typical language development (Dibbets et al., 2006).

Attention

Attention problems and language problems often present comorbidly. with most studies finding co-morbidity to be approximately 30-50% (Redmond, 2016). Language problems have been shown to contribute to problems with attention, although this effect is not significant when executive functioning is included in the model (Karasinski, 2015). Some aspects of language have been found to be associated with core aspects of ADHD, including using self-directed language, internalizing language, forming mental representations, and using language to self-regulate behaviors (Barkley, 1997).

Academic performance

The ability to perform well in academic subjects relates to language ability. Shanahan and Shanahan’s (2008) model highlights the specific linguistic skills needed for academic success. In this model, basic literacy is the foundation. Basic literacy is primarily mastered during the early elementary grades, and includes recognizing high-frequency words, decoding, and understanding the conventions of print. Intermediate literacy, typically mastered by the end of middle school, pertains to general comprehension, understanding the meanings of common words, decoding low-frequency words, self-monitoring comprehension, and reading fluently. Disciplinary literacy, the top level of the model, is comprised of the specialized linguistic skills needed for mastery of specific academic subjects. This theory suggests that language ability underlies the mastery of each academic subject. Students begin to attain disciplinary literacy in middle school and high school, but some students do not achieve mastery for each subject.

Summary

The constellation of deficits that can be exhibited by children with language disorder may result in significant academic and social challenges. It is important to consider how these processes together impact an individual child. The extent to which each of these constructs is a strength or area of need varies, and each individual must have a thorough interdisciplinary evaluation in order to determine the best plan to facilitate academic and social success. In speech-language pathology, it is often stated that we do not have a “cookbook” that tells us what to do with each individual, and this is true. We must use the best evidence available and consider it in relation to the individual and the context in which we are seeing them. In school-based practice, collaboration with our colleagues, including regular and special education teachers, psychologists, social workers, and administrators is paramount to making a positive impact on our students.

References

Baddeley, A. (2010). Working memory. Current Biology, 20(4), R136-R140.

Barkley R. A. (1997). Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: Constructing a unifying theory of ADHD. Psychological Bulletin, 121(1), 65-94. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.65

Ellis Weismer, S., Evans, J., & Hesketh, L. J. (1999). An examination of verbal working memory capacity in children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 42, 1249–1260.

Ellis Weismer, S., Plante, E., Jones, M., & Tomblin, J. B. (2005). A functional magnetic resonance imaging investigation of verbal working memory in adolescents with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 48, 405–425.

Im-Bolter, N., Johnson, J., & Pascual-Leone, J. (2006). Processing limitations in children with specific language impairment: The role of executive function. Child Development, 77, 1822-1841.

Karasinski, C. (2015). Language ability, executive functioning, and behavior in school-age children. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 50(2), 144-150.

Lehto, J., Juujärvi, P., Kooistra, L., & Pulkkinen, L. (2003). Dimensions of executive functioning: Evidence from children. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 21, 59-80.–68.

Macdonald, M., & Christiansen, M. (2002). Reassessing working memory: Comment on Just and Carpenter (1992) and Waters and Caplan (1996). Psychological Review, 109, 35-54.

Miyake, A., Friedman, N., Emerson, M., Witzki, A., & Howerter, A. (2000). The unity and diversity of executive functionsand their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cognitive Psychology, 41, 49-100.

Montgomery, J., & Evans, J. (2009). Complex sentence comprehension and working memory in children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 52, 269–288.

Nelson, N., Plante, E., Anderson, M., & Applegate, N. (2022). The dimensionality of language and literacy in the school-age years. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 65, 2629-2647.

Shanahan, T., & Shanahan, C. (2008). Teaching disciplinary literacy to adolescents: Rethinking content area literacy. Harvard Education Review, 78, 40–59.

St. Clair-Thompson, H., & Gathercole, S. (2006). Executive functions and achievements in school: Shifting, updating, inhibition, and working memory. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 59, 745-759.

van der Sluis, S., de Jong, P., & van der Leij, A. (2007). EF in children, and its relations with reasoning, reading, and arithmetic. Intelligence, 35, 427-449.