Introduction to Language Disorders

To begin the study of language disorders, one must first understand what is meant by language. Language is defined as a social tool, used mostly in conversations, that is a rule-governed system of abstract symbols. This construct differs from speech, which a verbal means of communicating, and is the oral expression of language. Both speech and language are used in communication, the sending and receiving of messages. Although many people use the terms speech and language interchangeably, it is important for speech-language pathologists to use the terms precisely. Similarly, the name of our field is speech-language pathology. It is important to use the full name, or abbreviate it as “SLP,” rather than to shorten it to speech teacher, speech therapist, or speech pathologist. Given that language disorders can and do exist in the presence of normal speech production, it is necessary to include the term language in our professional title. This helps to signal to potential referral sources that we can help with more than speech sound disorders. The term pathologist refers to one who engages in “the scientific study of the nature of disease and its causes, processes, development, and consequences (“pathology,” 2020), whereas therapist is defined as one who specializes in a type of therapy (“therapist,” 2020). Therapist, though accurate, does not quite convey the in-depth study of disorders undertaken by SLPs. I will note that in some countries, such as the UK, the term speech-language therapist is used.

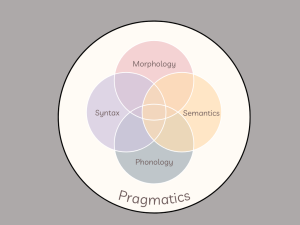

Language has been divided into five components: syntax, morphology, phonology, semantics, and pragmatics ([latex]Bloom & Lahey, 1978[/latex][latex]null[/latex]). Syntax refers to the rules governing sentence structure. This includes word order, clausal structure, and the need for a noun phrase and a verb phrase to form a sentence. Morphology pertains to the combination of the smallest grammatical units, termed morphemes. Free morphemes stand alone and have meaning. Bound morphemes must be attached to a free morpheme. Bound morphemes can be inflectional or derivational. Inflectional morphemes are used to mark grammatical constructions, such as tense, plurality, or possession. Derivational morphemes change the word class or word meaning. Phonology refers to the sound system of the language. This construct involves how speech sounds, or phonemes, can be put together to form words. Together, syntax, morphology, and phonology constitute the form of language. Semantics refers to language content. Semantics involves the meaning of language. Basic constructs within semantics include vocabulary, synonyms, antonyms, multiple-meaning words, inferences, and definitions. Pragmatics encompasses the social aspects of language, or use of language.

Form, content, and use have historically been represented as three separate, yet overlapping, components of language. In contrast, this book’s framework subscribes to a functionalist model of language (Owens, 2012). The functionalist model conceptualizes pragmatics, or use, as the overall organizing component of language, with syntax, morphology, phonology, and semantics as equal, overlapping components (Fig. 1.1).

The emphasis on pragmatics in the functionalist model highlights that language is a social tool used for interaction. This fits within a social interactionist theoretical perspective. The functionalist model is a communication-first approach that targets language as a vehicle for communication. Natural communicative contexts, such as conversation, are emphasized, and generalization is considered from the beginning of any intervention program. Intervention is family-centered and environmentally based, and changes to the context, in addition to changes to the child’s behaviors, are considered (Owens, 2012).

Language has also been characterized as receptive, or what is understood, vs. expressive, or what is produced (Rapin & Allen, 1983). Many language tests are comprised of subtests aiming to measure receptive or expressive language. However, current evidence suggests that tests labeled receptive or expressive do not actually measure separate constructs (Tomblin & Zhang, 2006; Language and Reading Research Consortium, 2017; Nelson et al., 2022).

Often, oral language (speaking and listening) and written language (reading and writing) have been viewed as separate constructs. However, recent evidence suggests that oral and written language are part of the same general language trait (Nelson et al., 2022). This highlights the role of SLPs in assessing and remediating disorders of reading and writing.

Current evidence suggests that separable dimensions of language ability are sound/word level knowledge of word structure vs sentence/discourse level knowledge of meaning-making components (Nelson et al., 2022).

References

Bloom, L. & Lahey, M. (1978). Language development and language disorders. Wiley.

Language and Reading Research Consortium. (2017). Oral language and listening comprehension: Same or different constructs?. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 60(5), 1273-1284.

Nelson, N., Plante, E., Anderson, M., & Applegate, E. (2022). The dimensionality of language and literacy in the school-age years. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 65, 2629-2647.

Owens, R. E. (2012). Language development: An introduction (8th ed.). Upper Saddle River: Pearson.

“pathology.” (2020). The American heritage dictionary of the English language (5th ed.). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Accessed December 9, 2019. https://ahdictionary.com/word/search.html?q=pathologist&submit.x=64&submit.y=21

Rapin, I., & Allen, D. (1983). Developmental language disorders: Nosologic considerations. In Kirk (Ed.), Neouropsychology of Language, Reading, and Spelling (pp. 155-184). Academic Press.

“therapist.” (2020). The American heritage dictionary of the English language (5th ed.). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Accessed December 9, 2019.https://ahdictionary.com/word/search.html?q=therapist&submit.x=0&submit.y=0

Tomblin, J.B., & Zhang, X. (2006). The dimensionality of language ability in school-age children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 49, 1193-1208.

a social tool, used mostly in conversations, that is a rule-governed system of abstract symbols

a verbal means of communicating, the oral expression of language

the sending and receiving of messages

the rules governing sentence structure

the smallest grammatical units that have meaning

the sound system of a language

mental representations of speech sounds

language content, the meaning

social use of language