4 What’s in it for Me? On Egoism and Social Contract Theory

Ya-Yun (Sherry) Kao

An egoist is known for their big ego. They are self-centered and care little about others. If you google the phrase “egoist,” almost all web pages that pop up teach you how to deal with them if you are so unfortunate as to encounter one. Given such negative connotations, it might surprise you to learn that some philosophers who are called “ethical egoists” argue that to act morally is to maximize one’s self-interest. At least on the surface, being ethical is not all about seeking self-interest. Morality requires us, for example, to keep promises, to treat others fairly, and to benefit those in need. It demands that we act not in our self-interest even if we can get advantages by breaking promises, treating others unfairly, or not helping the needy. Why then should we follow ethical norms that restrict our choices? What exactly is the relationship between ethics and self-interest?

This last question is the central question that we will focus on in this chapter. We will see how three different views, known as psychological egoism, ethical egoism, and social contract theory, address this question. Before we dive into details about each theory, here is a rough picture: Psychological egoism claims that true altruistic behavior is nothing more than wishful thinking because everything we do is by definition self-serving. Ethical egoism goes a step further, arguing that even if we could be unselfish, we can ignore any demand that ethics makes on us because we should put ourselves first. Finally, social contract theory claims that ethics itself is rooted in self-interest, that is, that we should really take others into account but only, ultimately, because doing so is in accord with what we want and need for ourselves.

Psychological Egoism

Psychological egoists argue that everything we do is self-serving even if we might think it is not. Self-sacrificial behaviors, such as using oneself as a human shield to protect others in a mass shooting, cannot disprove psychological egoism, because people who sacrifice themselves are not motivated by altruistic concern. Rather, they simply do what they most want to do. Sacrificing one’s life happens to be what one most wanted to do in those circumstances. Given that doing what one most wants to do is in one’s self-interest, one’s “self-sacrificing” behavior is again egoistic. Altruism is nothing but an illusion.

However, if doing what I am motivated to do is always self-serving, then trivially there is a sense in which all my actions are self-serving. To avoid this charge, an egoist needs to avoid interpreting psychological egoism as saying that, whatever the action one intends to do, it is always self-serving by definition. Perhaps a better strategy for a psychological egoist is to emphasize one does an action X always in order to further one’s self-interest. We act only for the sake of promoting our own best interest.

Many philosophers agree that the ultimate goal of one’s action is to further one’s best interest; what they disagree on is how to understand the idea of “one’s best interest.” Aristotle (384-322 BCE), for example, argues that eudaimonia (his term for the “happiness” that arises from a completely fulfilled life) is a rational agent’s ultimate goal. Stoics, on the other hand, argue for virtuous or excellent activities without pleasure. Still others, like Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677), argue that the ultimate goal of one’s actions is to realize oneself or develop oneself. To make this idea appealing, an egoist must flesh out the idea of self-realization or self-development, which in turn involves specifying what is ideal to pursue.

Max Stirner (1806-1856) proposes that the ultimate goal of one’s action is self-governance and to achieve it one need not take others’ interests into consideration.[1] To Stirner, “I” is absolute: “For me, you are nothing but—my food, even as I too am fed upon and turned to use by you. We have only one relation to each other, that of usableness, of utility, of use. We owe each other nothing, for what I seem to owe you I owe at most to myself” (Stirner [1844] 1995, 263). If you accept the psychological egoist view that one’s ultimate goal is always one’s own self-interest, Stirner’s picture of human interaction may not surprise you. Any moral obligation to others is subject to one’s own self-interest. As he puts it, “one must break faith, yes, even his oath, in order to determine himself instead of being determined by moral considerations” (210). Acting for the sake of another person’s interest is impossible.

One of the chief objections to psychological egoism is that it is an example of a non-falsifiable theory. It is very unlikely that one can know for certain how much one’s own motivation is of egoistic concern or of altruistic concern. This difficulty has to do with the fact that one can hardly know for sure about one’s own deep-down motivation. It can work in both ways. On the one hand, it gives psychological egoists an opportunity to argue that even a person who emphasizes that she does charity for an altruistic reason might, deep down, deceive herself. On the other hand, precisely because it is difficult to be certain about one’s own deep-down motivation, psychological egoists’ assumption that deep down we are all self-serving seems unwarranted. A recent empirical study even challenges the dichotomy between egoism and altruism by showing that people who are capable of expressing extreme altruism are labeled high in narcissism (White, Szabo, and Tiliopoulos 2018).

Here are the key take-away points: psychological egoists attempt to persuade us that we can never be truly altruistic and hence a truly realistic account of human behavior would have no place for anything remotely resembling ethics, if “ethics” requires us, at least sometimes, not to pursue our own self interest. But given that we hardly can know for sure our own deep-down motivation, we might still be altruistic. Ethical egoism, on the other hand, argues that even if we can, we should not be altruistic.

Ethical Egoism

While psychological egoism claims that the ultimate goal of one’s action is one’s own self-interest, ethical egoism claims that one should pursue one’s own best interest. The basic idea of ethical egoism is this: promoting one’s own best interest is in accord with morality. In its strongest form, ethical egoism claims that one acts morally if and only if one promotes one’s own best interest. In this section, we will discuss and evaluate Adam Smith’s and Ayn Rand’s ethical egoistic claims. We will end up with learning the biggest problem with ethical egoism, which serves as a transition to our next topic: the social contract theory.

Adam Smith (1723-1790) famously argues for egoism as a practical ideal in economics: Each businessperson promoting their best interest would most effectively promote the common good, given that the “invisible hand” (i.e. free market) would coordinate individual economic activities. In other words, if both buyers and sellers pursue nothing but the best deal for themselves, a win-win situation will ensue. Another daily-life example of how ethical egoism brings out the socially optimal outcome is competitive sports. The fact that each team is out to win produces the optimal outcome: if the players played without keeping score, or if the weaker team reaped the same rewards, the game would be boring to watch and the players would not reach their full potential. In other words, only when every player promotes their best interest (i.e. playing to win) would the best outcome ensue (i.e. we will enjoy watching the game and the players will reach their potential).

According to Smith, the successful function of the invisible hand depends on laissez-faire capitalism. He bases his analysis of social institutions and behavior upon principles of human action, the starting point of which is a form of ethical egoism:

Every man is, no doubt, by nature, first and principally recommended to his own care; and as he is fitter to take care of himself than of any other person, it is fit and right that it should be so. (Smith [1759] 1976, 82)

Although he believes that one should first pursue one’s own best interest, Smith does not advocate being a selfish, cold-blooded person. Instead, he argues that mutual kindness is necessary for happiness (Smith [1759] 1976, 225). Starting from our natural drive of trying to share others’ feelings as closely as possible, we adjust our feelings to the feelings of people we are concerned with and in this process we eventually develop virtues (110-133, 135-136). Of two principal virtues, justice and beneficence, the exercise of beneficence “deserves highest reward” (81). Here is a rough picture: Given our natural drives and our social condition, we are on the path of developing virtues, the most important of which is beneficence. Yet given that mutual kindness is necessary for happiness, we can say that practicing kindness is necessary for one’s own best interest. In benefiting another person, one is still pursuing one’s own self-interest.[2]

Ayn Rand (1905-1982), who also argues for ethical egoism and laissez-faire capitalism, however, argues that selfishness is a virtue. Altruism, which demands self-sacrifice, is even immoral. According to her, life is the ultimate value, and hence “no society can be of value to man’s life if the price is the surrender of his right to his life” (Rand 1964, 32). Concerned for the survival of civilization, she condemns altruism for being responsible for destroying the civilized world. Altruism is also responsible for making totalitarian regimes such as Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia possible, given that altruism holds

death as its ultimate goal and standard of value—and it is logical that renunciation, resignation, self-denial, and every other form of suffering, including self-destruction, are the virtues it advocates. (Rand 1964, 34-35)

Given that humans are rational beings, and that life is the ultimate value, “rational selfishness” is what one should pursue (25-31). To act rationally is to put one’s own interest first. According to Rand, not only is promoting one’s own best interest rational, it is also morally correct.

Without the burden of proving empirically that everyone must always act out of self-interest, ethical egoism is more appealing than psychological egoism. However, the biggest challenge to ethical egoism is that it lacks authoritative regulation of interpersonal conflicts of interest. Let me use an example to illustrate this point. Suppose my grandfather indicated in his will that I am his sole heir and suppose also that he is not bothered by any severe sickness. Suppose my cousin has been working her way to replace me as the sole heir and suppose that I am in a bad situation which requires a lot of money that I don’t have. Can it be morally wrong for me to kill my grandfather to ensure that I get the money now? Ethical egoism cannot answer this question, because from my perspective it would not be morally wrong but from my grandfather’s perspective it would be, and there’s no way to adjudicate between these perspectives.

Someone might also argue that ethical egoism borders on being incoherent. If what ethical egoism advocates is that everyone should do what is in their best interest, it seems confusing, if not outright inconsistent, that ethical egoism argues that doing so is how we promote the social good (i.e., the good that goes beyond the scope of self-interest). It seems self-contradictory to care about promoting social good while caring only about promoting one’s own best interest. Whether this objection is damaging to ethical egoism depends on whether promoting social good is fundamentally incompatible with promoting one’s own best interest. Smith apparently thinks that they are not fundamentally incompatible because he finds a way to incorporate the virtue of benevolence into his ethical egoism. Whether he is successful in doing that (i.e. whether his assumption that we have a natural tendency to care about others’ welfare fits well with ethical egoism) is another question. But the challenge seems to apply to Rand. If, as Rand argues, one should promote one’s own good and altruism is immoral, then it is confusing as to why she concerns herself with the issue of the survival of civilization (which presumably promotes the common good).

The biggest problem for ethical egoism is that it fails to be a moral theory because it cannot deal with interpersonal conflicts of interest. Only asking people to pursue their individual interests is not enough. As countless examples show, we can all benefit much more from cooperation. The issue of coordination is crucial given interpersonal conflicts of interest. Concern for coordination leads us to the last topic of this chapter: social contract theory.

Social Contract Theory

The basic idea of social contract theory in ethics is that ethical rules are sets of conventionally established limits we impose on ourselves in keeping with our own longer-term interests. This answers two fundamental questions about morality, namely, what is required and why we should obey. What is morally required is what we, as rational and self-interested agents, do or would agree upon. The reason why we should obey is because we have agreed, or would do so if we were being fully rational. Social contract theory shares the core assumption of egoism that we are self-interested and rational agents. However, realizing that living together in a society requires a set of rules for social cooperation, social contract theory provides a justification for why we should coordinate with others. Unlike egoism which cannot provide an impartial regulation of interpersonal conflicts of interest, social contract theory not only provides a way to handle conflicts of interest but also provides a justification for it. Given extra assumptions about human nature, we might end up following Thomas Hobbes or John Rawls. But both agree that moral rules are essentially conventional and binding only to the degree that we see them as serving our own interests.

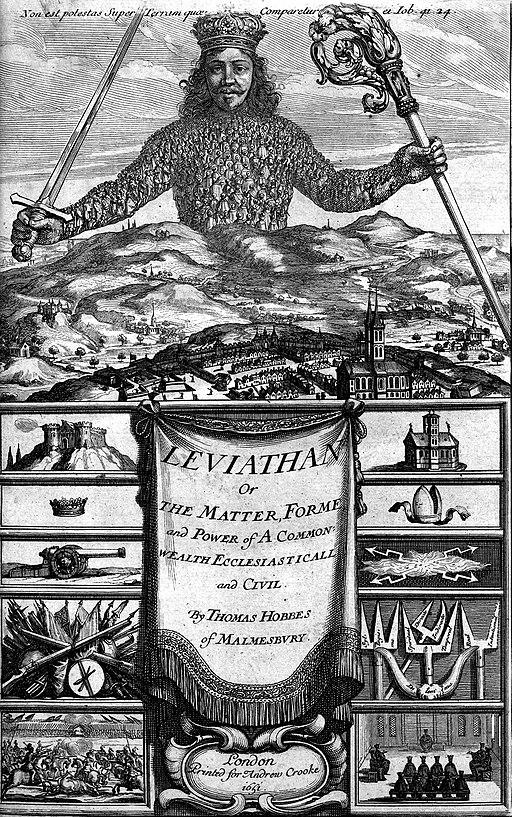

If moral and social rules are conventional, what would life be like without such rules, and how would this establish a motivation for defining and then following such rules? In particular, given that we are self-interested, why would we agree to obey a set of rules that sometimes limit our own self-interest? According to Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), the pre-political natural state of humanity, which he imagines as “the state of nature,” is a war of all against all in which people’s lives are “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short” (Hobbes [1651] 1996, 89). This miserable picture is derived from the following empirical and normative assumptions: his empirical assumptions are that people are sufficiently similar in their physical and mental faculties that no one is invulnerable and we all fear death (86-87, 90). His normative assumptions are that each person in the state of nature has the liberty to preserve their own lives and a right to do whatever in one’s opinion is necessary for survival; he calls it “the right of nature.” There is no constraint on the right of nature; “every man has a right to everything, even to one another’s body” (91). Given that resources are limited and we are all vulnerable in the process of exerting our rights of nature, Hobbes paints the state of nature as hell. Hobbes then envisions that we start to form social conventions based on mutual advantage. For example, although in the state of nature there is nothing inherently wrong in harming you, I would be better off by refraining to do so if everyone else does the same. A social convention against injury is thus formed. Hobbes calls such a convention “a law of nature.” The fundamental law of nature is “to seek peace, and follow it,” whereas the upshot of the entire set of laws of nature is “that law of the Gospel: ‘whatsoever you require that others should do to you, that do ye to them’” (92). In short, Hobbes’s social contract theory claims that moral requirements are nothing but social convention that we as rational and self-interested agents agree upon for the sake of survival. Given that everyone’s life is vulnerable in the state of nature, it is mutually advantageous to obey the social convention.

As a reader, you might wonder whether Hobbes’s story of the state of nature ever happened. But how damaging is it to his moral theory if it turns out that in history people were never in the state of nature? Some people adopt a hypothetical strategy, arguing that people would have agreed upon the laws of nature were they in the state of nature. But a hypothetical agreement lacks the strength of a real agreement. I cannot demand you to fulfill a hypothetical agreement that you financially support me for the rest of my life, even if doing so would be in your best interest, because we did not actually agree to this at a prior time. As far as I can see, the real problem is whether understanding moral requirements as social conventions, the obeying of which is of mutual advantage, has enough force to ensure that everyone does obey.

David Gauthier, a contemporary Hobbesian, argues that social conventions agreed upon as moral requirements are derived from a bargaining process over mutually advantageous conventions. Given that social conventions are derived from bargaining, people with the upper hand have little incentive to produce a fair convention for the weak. After all, there is little to gain from cooperating with the weak and little to fear of their retaliation. Even if a fair convention that takes care of the interests of the weak is agreed upon, it does not guarantee that the strong will obey. After all, whether it is advantageous to follow a particular convention also depends on one’s bargaining power. In Gauthier’s theory, defenseless or people with disabilities “fall beyond the pale” of morality (Gauthier 1986, 268). That is to say, moral constraints will only arise if people are roughly equal in power. Were I a person with disabilities, I would be left out of moral consideration. This seems to push us back to a situation close to Hobbes’s state of nature, a situation where the strong exploits the weak. If moral requirements are all about the strong exploiting the weak, we don’t even need to call them “requirements” because humans easily, if not naturally, act that way.

Another contemporary social contract theory—Kantian contractarianism—has an entirely different outlook even though it shares the same assumption that we are rational and self-interested agents. Kantian contractarianism bases the social contract on a natural equality of moral status which makes each person’s interests a matter of impartial concern. It has roots in Immanuel Kant’s (1724-1807) moral theory (see Chapter 6) which takes each person as “an end in itself,” an intrinsically valuable moral status, and demands each person act in accord with universalizable personal policies (which Kant calls “maxims”) as a member of the community (Kant [1785] 2002). Following Kant’s idea that our equal status (as an end in itself) demands us to act in an impartial way in a community, John Rawls (1921-2002) develops a social contract theory that answers the question “What terms of cooperation would free and equal citizens agree to under fair conditions?” Whereas Hobbes’s social contract is based on the state of nature, Rawls’s is based on “the original position of equality” where people, as free and equal beings, collectively figure out the social contract that they agree upon. To avoid the strong having dominant bargaining power over the weak in the process as Gauthier paints it, Rawls stipulates that people in the original position make the bargain under a “veil of ignorance,” that is, people have no idea of their natural talents and their social position. Because people are not aware of any natural or social differences between them, they are equal and more likely to act toward each other in a non-biased, impartial way. Notice that Rawls’s idea of the “original position” does not refer to any actual historical event. Rather, it is a device that helps us vividly imagine a fair and impartial point of view, when we reason about fundamental principles of justice. To maximize one’s own best interest in this condition, Rawls believes, people will come up with and endorse a fair contract in an impartial way. If inequality is unavoidable, it must be justified to those made worse off, and perhaps even subject to their veto. Hence, vulnerable people won’t be excluded from the domain of morality as they will be in Gauthier’s picture. Rawls assumes that people will act benevolently if they are rational, self-interested, and behind the veil of ignorance. Thus, the original position “represents equality between human beings as moral persons” (Rawls 1971, 190).

Conclusion

Although it is hard to prove that everyone must always act out of self-interest, it is probably true that we have the tendency to act for the sake of promoting our own best interest. The starting point of both egoism and social contract theory is that we are self-interested and rational beings. However, basing morality on self-interest alone does not get us far and even defeats the idea of morality. Why should we continue to follow moral rules in cases where following them would not in fact be in our personal best interest? A social contract theory, be it Hobbes’s, Gauthier’s, or Rawls’s, can still suffer from the prisoner’s dilemma where everyone rationally acts in a self-interested way even when doing so is detrimental for the good of all involved.[3] For example, my roommate and I agree that it is best if everyone helps keep the place clean. Out of self-interest, it is rational for each of us to find some excuse not to clean up. As a result, no one actually keeps the agreement and our place probably is a mess. Moral requirements based on agreement thus still lack sufficient force to ensure that everyone in fact does comply. Why should we follow norms that restrict our choices in certain cases? In the previous chapters, we have seen that the authority of cultural norms, religious rules, and appeals to nature do not conclusively show why it is that we should follow the rules. In this chapter, we have seen that appealing to self-interest is also not sufficient to account for such rules. Instead, we need to derive more objective ethical principles from reason. Rawls’s Kantian idea is a move toward objective and impartial ethical principles. The following chapters explore other philosophers who base such principles upon reason.

References

White, Daniel, Marianna Szabo, and Niko Tiliopoulos. 2018. “Exploring the Relationship Between Narcissism and Extreme Altruism.” The American Journal of Psychology 131(1): 65-80.

Gauthier, David. 1986. Morals by Agreement. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hampton, Jean. 1986. Hobbes and the Social Contract Tradition. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hobbes, Thomas. (1651) 1996. Leviathan, ed. Richard Tuck. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kant, Immanuel. (1785) 2002. Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals, ed. Allen Wood. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Rand, Ayn. 1964. The Virtue of Selfishness. New York: Signet.

Rawls, John. 1971. A Theory of Justice, reissue ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Smith, Adam. (1759) 1976. The Theory of Moral Sentiments, eds. D. D. Raphael and A. L. Macfie. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.

Stirner, Max. (1844) 1995. The Ego and Its Own, ed. David Leopold. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press.

Vallentyne, Peter, ed. 1991. Contractarianism and Rational Choice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Whether Max Stirner is a psychological egoist is disputed. David Leopold, for example, argues that he is not. (For Leopold’s argument, see Stirner 1995, xxiv–xxv). ↵

- We should note that Smith is not a thoroughgoing egoist who argues that morality is founded upon self-interest. According to Smith, moral rules stipulate what is fit and proper to be done or to be avoided and these rules are not dictated by self-love (159). It is the “impartial spectator,” not self-love, that shows us “the propriety of resigning the greatest interests of our own, for the yet greater interests of others” (137). ↵

- How Jean Hampton criticized Hobbes can also apply to contemporary contractarianism. She doubts whether having a social contract can indeed function as well as intended. Suppose the war of all against all is triggered by greed or fear; there is no guarantee that a person who was greedy before the contract is drawn up will stop being greedy after the contract is drawn up. Moreover, having a social contract seems to not guarantee that we can be entirely free of the prisoner’s dilemma. That is, given that there is no guarantee that another person will keep their end of the bargain, it’s better for me not to keep my end of the bargain. No matter how harsh a punishment we set up for a contract violator, there is always someone who is willing to take the risk. In short, Hampton’s point is that whatever makes a person unable to cooperate before a contract is drawn up might not go away after a contract is drawn up. A contractarian cannot guarantee that (Hampton, 1986). Gauthier’s response is that a contract can avoid the problem if the contractors realize that they are in an environment of like-minded individuals (Gauthier 1986, 160-166). Whether Gauthier’s response really solves the problem, however, is disputed (see Vallentyne 1991). ↵