7 Music of West Africa

Robin Armstrong

Introduction

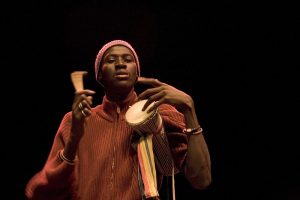

Listen to the song and watch the performance of the song “Immigres” by Youssou N’Dour in a 1987 live performance (Music begins about at 1:00 after an introduction).

Identify the musical elements that sound familiar to you, then listen to it again and identify parts of the music that seem different than what you usually hear.

As you watch the performance, ask yourself how it compares to other music performances that you have enjoyed. Which instruments are the same as what you normally see and hear? Which instruments are different? In addition to the standard rock drum set and the electric bass, we can see and hear sabar drums and the smaller tama (or talking drum) both of which come from West Africa.

This chapter begins a unit on several musical styles from the continent of Africa. Chapter 7 (this chapter) presents a broad overview of musical and cultural traits common in music from West Africa. Chapter 8 discusses Senegalese music and culture, and Chapter 9 discusses music and culture from the Republic of Ivory Coast.

Unit Learning Objectives

- Identify musical aesthetics, stylistic elements and instruments specific to west African music.

- Analyze music through listening to recorded performances of west African music

- Identify cultural values and traits specific to west African cultures.

- Connect musical traits to cultural traits specific to west African music.

- Explain how music making and music appreciation are part of the human experience.

The Continent of Africa

Africa is the second largest continent in the world at 11.6 million square miles (the United States is only 3.8 million square miles). The continent has six geographic and cultural regions that can be seen in this African regions map: West Africa, (which includes the two countries in this text: Senegal and the Republic of Ivory Coast and is shown in the middle left on the map in bright green), Equatorial/Central Africa (shown in brown on the map), Eastern Africa (shown in red), Southern Africa (yellow at the bottom of the map), the Sahel, which is just below the Sahara Desert (and shown in khaki green on the map), and North Africa, which includes the Sahara Desert up to the Mediterranian Ocean (and is shown in light green on the map). Because North Africa is separated from the rest of the continent by the enormous Sahara Desert, the world’s largest subtropical desert, the countries of North Africa including Egypt, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia are culturally (and in many cases geographically) closer to the Middle Eastern countries of Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Israel, Iran and Iraq than they are to the cultures and countries of Sub-Saharan Africa. This chapter includes music of West Sub-Saharan Africa.

Sub-Saharan Africa includes all types of geography and topography from arid desert to lush rainforests, and towering mountains to luxurious beaches. People live in all types and sizes of towns, from the tiniest villages to enormous cities. While there are only 54 countries in Sub Saharan Africa, there are thousands of distinct ethnic groups or tribes with unique cultures and languages. There is not a one-to-one correspondence between country and ethnic group. All countries contain multiple ethnic groups (and languages), and many ethnic groups live in more than one countries. Countries are political units rather than cultural entities.

From the beginning of the European exploration of Sub-Saharan Africa and the slave trade of Africans in the fifteenth through nineteenth centuries, the western world has negatively stereotyped Africa and Africans. Even today the fictional character Tarzan (first created by the American author Edgar Rice Burroughs) is often better known than the factual history of the African empires and their rich scholarly and artistic contributions to the world. The two videos African Empires and African Kingdoms: 5 Powerful Kingdoms to know describe a few of the richer, older African empires. Many misconceptions about modern Africa also abound, as well. The two videos African Stereotypes That We Need to Stop and Top 5 Myths and Misconceptions About Africa counter a few myths with accurate information.

Common Musical traits among different African cultures

Despite the enormous musical and cultural diversity throughout Sub-Saharan Africa, there are several principles fundamental to most of these cultures that shape many styles of music throughout the continent: First, musical participation is essential to daily life, and two musical structures facilitate participation: call and response and cyclical patterns. Both call and response and the cyclical use of patterns make it easy for people of all skill levels to join in the musical event. Second, music is inclusive and apt to be influenced by, and includes sounds from outside the musicians’ area and culture. Musicians collect musical sounds from all around them, and musical styles all over the world, to incorporate into their songs. Third, the musical element that is the most prominent in most musical styles from all over Sub-Saharan Africa is rhythm, and virtually all musical instruments indigenous to Africa focus on rhythm even if the instruments are not drums. Both wind and string instruments can be played to highlight rhythm rather than melody, and wind and string instruments in Africa normally play rhythmic patterns rather than long melodies. See Appendix II for more information on the musical element rhythm.

Participation in Music is Essential

Music is not a frill but a vital part of human contact and interaction. … Performance permeates the life of African communities across the continent. Music, as many Africans view it, is not a thing of beauty to be admired in isolation. … Music is so much more than a frivolous expression that can be added on as an extra entertainment. Rather, it is a critical part of the lifeblood of human interaction in African communities. -Reed and Stone (2014)

Music is ubiquitous in Africa, integrated within all parts of life, from everyday activities to special celebrations, from daily employment and chores to the most sacred of rituals. While for many people in the United States, listening to music is an important part of life, for most people in Sub-Saharan Africa, merely listening is not enough: participation is essential. One indication of the importance of making music can be seen in the elaborate decorations of many musical instruments. Using this link, visit the website of the Smithsonian Museum of African Art to peruse their musical instrument collection. You will see instruments that are works of visual art. The decorations on these instruments indicate just how important they are, for if not important no one would have taken the time to decorate.

Participation can take many forms. In addition to making music on instruments, participants clap along with the rhythms, sing, and/or dance. As long as everybody takes part, the type of participation doesn’t matter. As these anecdotes illustrate, what matters is that everyone joins in.

A group of tourists have arrived in the town of Ho, in the Volta region in Ghana, (West Africa). They are sitting on benches on three sides of a dirt square waiting for what they have been told is a concert of traditional Ewe music. Musicians enter the square and start singing and dancing with the drums. By the end of the evening there is no separation between the performers and audience, for everyone is in the square dancing. From the start of the music the performers first invite, then insist, that the people sitting and watching join in.The Kennedy Center in Washington DC is the most elite performance space in the capital of the United States. The large concert halls feature performances of symphonies and operas where the audience sits quietly and enjoys the musicians on the stage. One night, a college class of students taking a course on African music attends a performance of the Senegalese musician Youssou N’dour. They sit in the balconies and can see both the stage and the audience in the best seating on the main floor. The main floor is filled with fans of this African musician, and as soon as the music starts the people stand up and begin to dance. The ushers, who are used to symphony and opera audiences, go through the audience to ask everyone to sit down when the song is done, but when the next song starts, they pop back up again. Halfway through the night, Youssou takes time from his singing to ask the ushers to let the folks dance because in his music everybody dances.

In African cultures, audiences do not sit and listen, they take part in making music and dancing, unlike in European cultures where most often audiences sit quietly and listen. Participation is an essential part of both traditional and contemporary popular styles. The performance Youssou N’Dour live @Paradiso 23/7/18 shows women from the audience going up on stage to dance for the performers and audience alike, and then shows the performers encouraging all members of the audience to wave their arms with the music. During the quarantine of the 2020/21 COVID-19 pandemic, when video conferencing replaced live performances, musicians still engaged audience participation virtually. In his 2021 New Year’s concert, the musicians on stage with Youssou N’Dour in the concert clip Youssou N’Dour – Bukki Yi – Clip Officiel engaged directly with audience members by pointing at them on many video conferencing screens, and then editing the video feed of some audience members into the published video clip.

The African culture of participation of course is not merely for the adults. Children, regardless of age, take part. Babies too little to walk dance because their mothers dance with their babies on their back. Musical events are not divided between children and adults, as these anecdotes demonstrate:

Residents of a small village in Ghana are looking forward to an evening musical event. In the middle of the afternoon, several children carry drums into the center of the village and start playing them. A little while later a couple of adults join them, and begin to guide their playing. A little while later, more people arrive and the event begins.The Kouyaté family is one of the most important Griot families of West Africa. [A Griot is a professional historian, storyteller, and musician (see Chapter 8). It is a family art, where one generation teaches the next ones]. Multiple generations of the Kouyaté family are teaching a one-week workshop for college music teachers held at the University of Maryland, on West-African drumming and dancing. Two of the teachers are a young couple with a toddler. Every day of this workshop the toddler joins the adult students in learning to play the djembe (a West-African drum) or dance, depending on what room he wanders into. When he tires of that activity, he simply goes into another room. It is clear to the adult students that the child had been doing that all of his short life, for the three-year-old is a much better djembe player and dancer than the workshop participants could be after only one week of workshop classes.

Participation by all members of the community, no matter their age, is essential in most Sub-Saharan African cultures. Most African musical styles reflect this cultural need for everyone to participate, for there are several common musical structures that are used to facilitate participation, including call and response and cyclical patterns.

Call and Response

The musical structure of call and response reflects and facilitates participation and is common to much music created throughout the continent.

Sidebar: Call and ResponseCall and response is the alternation and exchange between two parts. This interchange sounds like a conversation, where one part makes a statement and another part responds. Frequently an instrumental or vocal soloist will start and an instrumental or vocal group will respond, but call and response is not limited to a soloist and group. Two soloists can exchange calls and responses, as can two groups. Call and response can also occur between musicians and dancers |

Call and response revolves around relationships between two entities, requiring interaction. This exchange can include instrumentalists, vocalists, and/or dancers as individuals or in groups. Sometime the response is the same as the call; this can easily serve to teach newcomers how to participate because all they have to do is mimic the call. In the middle of his song “Immigres” that you listened to above and you can revisit with this link – [Youssou N’Dour – Immigres (Live in Athens 1987)] N’Dour begins an extended section built exclusively on call and response. At 5:47 many of the accompanying instruments have dropped out, and N’Dour begins a section built on this type of call and response. He sings a phrase, which is then repeated by a backup singer. Then he shifts to just the words “Hey Hey” at 6:00 and the audience begins to respond. Because the pattern is so short and simple, everyone in the audience can participate even if they have never heard the song before.

A different type of call and response involves a simple refrain that is used as a response while the call varies. For example, in the Kpanda Dance of the Baule people from the Republic of Ivory Coast, the response is a repeated refrain not dependent on the call. This also teaches newcomers how to participate because they learn through repetition. Additionally, when the response is a repeated refrain and not dependent on the call, the call can be the foundation that allows a virtuoso to improvise in between refrains. In this way, the structure of call and response allows and facilitates participation by performers of all levels from the very beginning to very advanced. It builds and maintains community because it requires participation.

Use this Spotify link to listen to the Kpanda Dance of the Baule people from the Republic of Ivory Coast. The bell, sticks (softly) and drum enter first. Then two singers begin and are answered by a group. Through the course of the song, the bell that entered first always plays the same pattern (a five note pattern with a short pause between notes 3 and 4 and a longer pause between notes 5 and the repetition of the pattern staring on 1: 1 2 3..4 5 …..1 2 3.. 4 5). The response that the group sings is always the same: a melody made up of only two alternating pitches with a pause after the first three notes. While the stick and the drum parts are harder to hear because they are in the middle of the texture and are more complicated, they too, consist of repeated patterns. Only the call seems to vary.

Patterns

Like the Kpanda Dance, much sub-Saharan African music is cyclic: The music consists of recurring patterns, most of which do not change through the course of the song. Like the bell pattern and the group vocal response in the Kpanda Dance, short patterns facilitate the participation of people who don’t know the song because short patterns are easy to learn and remember, and participants can come in after they have heard the pattern sufficient times to learn it. The drum and stick parts as well as the main melody in the call are more difficult to learn, which allows more skilled performers to participate at a more advanced level. As with the use of call and response, the use of patterns allows everyone to participate regardless of knowledge and experience. Moreover, songs built on patterns like the Kpanda Dance require community participation since they cannot be performed by only one person: a full community is essential to perform songs based on multiple patterns.

Collection and Aggregation

Another principle common among most Sub-Saharan African cultures is that music is inclusive, and – in a very positive sense – acquisitive. People gather all musical sounds and ideas that they come across, repurpose them, and incorporate them into new creations. A melody heard in one place may subsequently be heard in another unrelated song somewhere else. Gathering and reusing music is a valued skill, considered “creative and clever and much to be admired” (Reed, and Stone (2014)). Sampling in Hip Hop is a modern type of aggregation using technology. Sampling, which is the use of previously recorded music from one song in another new song, has been part of the construction of rap since the music began in the 1970s, and is one of many African traits retained in African-American music. Coupé-décalé, which will be discussed in Chapter 9, is a very modern style of music from the Ivory Coast combining traditional Ivorian rhythms with rhythms from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and adds computer synthesized layers, bass and drums used in many global commercial styles of music. Mbalax music from Senegal, which will be explored in Chapter 8, combines traditional instruments like the kora and sabar with Sufi Muslim singing from Arabic cultures, together with style traits from popular music from the United States and from the Caribbean Islands.

Rhythmic Focus

Finally, another common principle in Sub-Saharan African music is that rhythm is the most important musical element. While Western music is full of long melodies and lush harmonies, West African music focuses on rhythm. We can hear this focus in the Kpanda Dance. While this piece has melodies in the call and in the response, these melodies are short and not nearly as arresting as the complicated rhythmic structures produced by hearing multiple rhythmic patterns at the same time. Music like this that has multiple simultaneous rhythms is polyrhythmic, which is a word that literally means “many rhythms.”

Throughout the many various West African musical styles the amount of melody shifts from little or no melody in music such as drumming from Burundi, to music sung by Griots which has long melodies to fit the texts of the long stories they tell. But these long tunes are still supported by multiple rhythmic patterns in the accompanying instruments, as we can hear in the song “Kelefa Ba” discussed in the next chapter. In this song, the melody with the text starts and stops, but the instruments play their rhythms continuously. So while some West African songs do have long melodies, all have a rhythmic focus.

Musical instruments

Musical instruments indigenous to Sub-Saharan Africa are built to play more rhythm than melody. Percussion instruments abound and are constructed from whatever natural resources are most prevalent. Many string instruments are normally constructed to focus on rhythm rather than melody; they are plucked, which gives a sharp rhythmic impulse. Because they only have a few strings, they are built to play only a limited number of pitches and play patterns rather than long melodies. Use this link to watch Ayub Ogada from Kenya demonstrate a lyre-type stringed instrument, called a Nyatiti. Just like most African stringed instruments only have a few strings, wind instruments normally only have a few holes. Since pitches change as musicians cover and release the holes in an instrument, when they only have a few holes, they can only play a few notes. This Spotify link will take you to a Kassena Dance from Ghana. After the drums begin the song, several different wind instruments enter, each playing only a few pitches in call and response to each other. The flutes used in Kassena dancing illustrate the close connection between the construction of the instruments and the values of musical performance. These flutes only have three holes, so they play patterns more than melodies. As they are made in sets, multiple people need to participate to play the song completely.

African musical instruments also reflect the wide diversity of African cultures and geographic regions, as well as the values of aggregation and collection. The underlying principle of construction of all African instruments is to use all available materials whether natural or manufactured. All natural materials can be used as instruments. Many instruments are made from wood, bone, and/or animal skins: whichever are most prominent in the region. Literally anything can be used, from musicians’ hands (clapping) to pounding on a lake, as this video showing musicians using the water of a lake as a drum demonstrates. Manufactured items can be made into musical instruments as well, such as this guitar made with an oil can. Many instruments are simple and easy to make, like a bow that uses a single string, while others are fancy and complex to make, such as the 21-string kora. All types of commercially-available instruments are used, of course, as seen in the Youssou N’Dour video above. Musicians in that performance play electric guitar, keyboard, saxophone, drum set, along with the hand-made sabar, and tama. The wide diversity of African instruments reflects the human, cultural, and geographic diversity of the continent. The almost infinite materials used, from natural to manufactured, reflects the cultural trait of aggregation and collection.

Moving forward

In the next two chapters, we will explore examples of both traditional and contemporary songs by African musicians. In Chapter 8: “Music in Senegal”, we are introduced to some African Griots, we meet international pop sensation Baba Maal, and we discover Mbalax. In Chapter 9: “Music of the Ivory Coast”, we learn about some traditional dances, meet some DJs and learn about Coupé Décalé. In each chapter we will study the songs within their cultural contexts so that we can fulfill our learning objectives by identifying the musical aesthetics, stylistic elements and instruments, analyzing the music through listening, identifying their cultural values and traits, connecting their musical traits to their cultural traits and explaining how music making and music appreciation are part of the human experience.

Works Cited

Reed, Daniel B. and Ruth M. Stone (2014). “African Music Flows” in Africa edited by Maria Grosz-Ngaté, John H. Hanson, and Patrick O’Meara. Fourth edition. Bloomington : Indiana University Press, 2014.

Media Attributions

- Sabar © Christophe Alary is licensed under a CC BY-ND (Attribution NoDerivatives) license

- Tama © Christophe Alary is licensed under a CC BY-ND (Attribution NoDerivatives) license

Call and response is the alternation and exchange between two parts. This interchange sounds like a conversation, where one part makes a statement and another part responds.